Photos: Preston Gratiot.

The first album Elvin Bishop played on wasn’t a chart-topper – it was a life-changer. For the raised-on-rock generation that credits 1965’s Paul Butterfield Blues Band for introducing it to the blues, the album was monumental – the audio equivalent of the scene in The Wizard Of Oz when the film shifts from black-and-white to color – and there was no going back.

“A whole lot of people have told me that,” the guitarist acknowledges. “And it sounds good every time. It really makes me feel good.”

Featuring the harmonica and vocals of its bandleader alongside the dual guitars of Bishop and the kinetic Mike Bloomfield, the band became a mainstay of the Fillmore scene and underground radio of the day, after years of seven-sets-a-night gigging in Chicago clubs. The only debate among converts was which album was more pivotal – the visceral, undiluted debut or the adventurous followup, East-West, a year later.

With Bloomfield’s departure to form the Electric Flag, Bishop took a more prominent role on 1967’s Resurrection Of Pigboy Crabshaw, but would stay with Butterfield for only one more album before moving to San Francisco and starting his own band.

It, too, became a fixture of the Fillmore and Bay Area club scene, and in fact was signed to Fillmore Records. Its first three albums (now available on the two-CD Acadia compilation Party Till The Cows Come Home) show the good-time band to be as much R&B and rock as blues.

But in 1974 Bishop was signed to the home of the so-called Southern rock movement (acts like the Allman Brothers Band, Wet Willie, and the Marshall Tucker Band), Capricorn Records. It was not that big of a stretch, thanks to Bishop’s Oklahoma roots, and he scored hits with “Travelin’ Shoes,” “Struttin’ My Stuff,” and the #3 “Fooled Around And Fell In Love.”

After a 10-year hiatus from the record bins, he returned to his blues roots with 1988’s Big Fun (on Alligator). But his three most recent albums are among his strongest – Gettin’ My Groove Back , the live Booty Bumpin’, and especially 2008’s The Blues Rolls On. Following the murder of his daughter, Groove (Blind Pig) was a catharsis – with the angry “What The Hell is Going On,” a slide instrumental treatment of the country hit “Sweet Dreams,” and a stark solo performance titled “Come On Blues.”

For The Blues Rolls On (Delta Groove), Bishop surrounded himself with peers, mentors, and the newest generation of blues players – from George Thorogood to Derek Trucks, from B.B. King to Mississippi’s Homemade Jamz Blues Band.

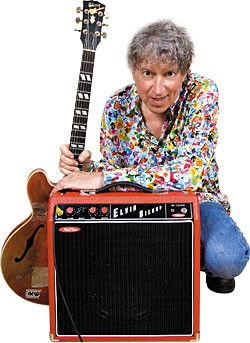

For nearly 35 years, Bishop has lived in the hills of Marin County, his home flanked by an impressive garden (where he grows all manner of herbs, fruits, and vegetables) and his recording studio, home of the trademark Gibson ES-345 he calls “Red Dog.” Drinking homemade apple juice in his studio, he spoke with Vintage Guitar about the National Merit Scholarship that brought him to Chicago, his blues apprenticeship there, the search for another Red Dog, and the concept behind the new CD – passing the blues tradition down to future generations the way the legends of Chicago blues passed it down to him.

Tulsa musicians like Leon Russell and J.J. Cale are a little bit older than you. Before you got the scholarship and moved to Chicago, were you exposed to the music scene in Tulsa much?

Well, that “little older” was significant. I was only 16 when I left Tulsa, so it was real hard to get into clubs. I managed to a couple of times, but basically I couldn’t get involved in the music scene. At that stage I was more of a listener. I tried to play guitar from the time I was maybe 14. But the only guitars I could afford, I’d go to the pawn shop, and I didn’t know how to pick one, so I’d always get one with the strings two inches off the neck. It’d hurt my fingers, and I’d try it for a month and then give up. Then I’d go somewhere and see the girls hanging around guitar players, you know, so I’d get the guitar out and try it some more. I finally stuck with it about the last year of high school. But nobody in my family was musical; there were no musicians in the neighborhood. It was pretty much like Bob Seger says – “Workin’ on mysteries without any clues.” Where things really busted wide open was when I got to Chicago. I could sit down with guys and see their fingers and see what they were actually doing. And guys were nice enough to help me out. I got lucky, and I met some real good teachers immediately – guys that just made you get it right.

You were born in ’42, so when you say “about 14,” that’s 1956. By then, rock and roll was already starting. But you would have been an adolescent when that transition happened.

Well, see, it was amazing, because up until that time, white people – unless you were into country – the best you were gonna be able to do was Frank Sinatra or “How Much Is That Doggy In The Window.” And then Elvis came in, and Jerry Lee, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry – and “Wow!” That just kicked in, and the hormones were kicking in at the same time, and the world was just exploding.

I lived on a farm ’til I was 10 or 11 years old. We didn’t have electricity. People these days are bombarded with sound and music from the time they pop into the world. In those days, TV wasn’t happening; there were no video games, no computers. The only time we heard any music, we had this radio – when the weather was right – with a big battery that weighed about five pounds. And when TV came in the early ’50s, there weren’t any appliance stores or Best Buys or Good Guys. You had to go the furniture store and stand in the window to look at it. And a TV was really more like a piece of furniture, because it was four or five feet high, three feet wide, with a 10″ speaker and a little round picture tube.

So rock and roll popped in almost out of a vacuum. That’s why when I go back and listen to the records I bought when I was a teenager, and I think, “I never realized, that’s way out of tune; there’s no balance to the way it’s recorded; by the time it’s done it’s twice as fast as it was in the beginning.” Because people’s ears weren’t sophisticated in those days. Now you can’t get by with playing out of tune; it’s just not allowed. Everybody’s got a finely tuned, sophisticated ear from hearing so much music. In those days, as long as it felt good, it was alright. That’s why the White Stripes are popular – because they’re going back to where it just feels good. Anybody can appreciate that.

There are some records from those days, like Bo Diddley’s “Before You Accuse Me,” where he totally goes to the wrong chord, and that’s what they pressed up.

Well, that was the best take there [laughs]! Listen to some of Fats Domino’s hits – I think either “My Blue Heaven” or “When My Dreamboat Comes Home.” It’s twice as fast at the end as at the beginning. And it was a hit.

I started listening to that stuff on the radio from the time it came in; I loved that rock stuff. Then a couple of years later, I heard blues coming in over [Nashville station] WLAC. Tulsa’s on a prairie – it’s flat – so late at night you could get stations from Alaska; there was another in Mexico, one in Shreveport, Louisiana. When I heard blues, I said, “That’s where the good part of rock and roll is coming from.”

When you were first playing guitar, did you take any lessons?

You know, I tried to take lessons for a couple of months, but the only guy I could find who gave lessons was an old dude who started me out with a Mel Bay book, doing tunes like “Bell Bottom Trousers” and “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” insisting I learn how to read. It wasn’t what I was after. So the lessons were such a drag, about five minutes after the lesson started he’d start telling me stories about the old days and different places he played. Spent most of the hour doing that, and then he’d say, “You study this other stuff at home.”

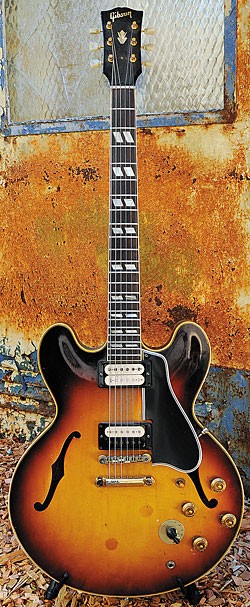

Bishop’s 1960 Gibson ES-345. Photos: Preston Gratiot.

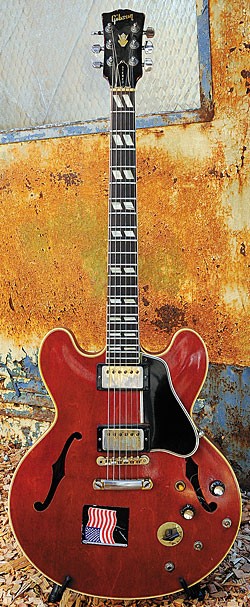

One of two Gibson Custom Shop ES-345s built to replicate Bishop’s “Red Dog.”

2004 Gibson ES-345.

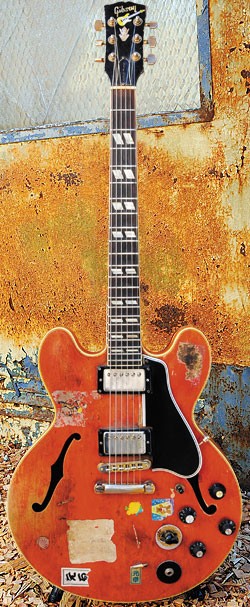

Elvin Bishop’s renowned “Red Dog” is a 1959 Gibson ES-345. Most of the stickers were applied by his daughter.

When your family moved to Tulsa, was it a move from rural to city life?

Yeah, we lived in what would now be called the suburbs. About 1952 or so, there was a big drought in Oklahoma. I lived on a farm in Iowa with my folks. I didn’t know there was anything else happening in the world. Like I said, we didn’t have any electricity or running water. I’d go to my grandfolks’ house, about 12 miles away, in a big town of 5,000. They’d have to drag me out of the bathroom, because I’d be flushing that toilet over and over (laughs) – “This is a miracle!”

Anyway, my dad took a load of hay down to Oklahoma during this drought, and they were paying big money, so he applied for a job and got hired at an aircraft plant.

You must have been an awfully good student to become a National Merit Scholar.

Well, you know what? I was a good test-taker, I think, is what it amounted to. Because I wasn’t a good student. But I got interested in blues, and it took over my mind, 100 percent. Which wasn’t a popular thing – not only in my family; there weren’t any other white people into blues, to speak of. But I loved it. So when I got that National Merit Scholarship, it was a great thing, because my family had no money, but I could go anywhere I wanted. I knew blues was in Chicago, so I found out there were two main colleges – Northwestern and University of Chicago. Northwestern is in a Jewish suburb 30 or 40 miles from Chicago, which I didn’t know, and University of Chicago was in the middle of the South Side ghetto – I didn’t know that either. But I flipped a coin and got the University of Chicago. Luckiest things that ever happened to me.

So music was your aim.

Yeah, education was just my cover story. I didn’t want to hurt my family’s feelings. They’d lived through the Depression, and there one guy way back who wasn’t a farmer; he was an engineer. He was the family hero. “You can be like your Uncle Glenn. He got a job with General Electric!” So I stuck with the school as long as I could, but I didn’t finish.

I just got real lucky. First day I was there I met a white guy playing guitar on some steps, drinking a quart of beer, playing blues, and it was Butterfield. At that time he played more guitar than he did harmonica. He used to play a little rudimentary harmonica, like Sonny Terry. Shortly after, he got interested in Little Walter and Muddy Waters and all that, and within six months he got as good as he was ever gonna get. Like what you hear about Robert Johnson – “Aw, that can’t be true” – I actually saw it with Butterfield. He was just a natural genius.

How long after you arrived at school did you discover where the blues clubs were?

First week I was in school, I went and made friends with the black guys working in the cafeteria. And they’d go every weekend to see Muddy Waters, Magic Sam, Howlin’ Wolf, Hound Dog Taylor, and they started taking me with them. I always had good common sense. It was dangerous, but it wasn’t as dangerous as it is now. There were no gangs, no crack cocaine. The South Side of Chicago had a little bit of the feeling of a Southern town. People were basically friendly, and as long as you didn’t do anything stupid, you could get by. And I always went with a group of guys – black guys. Including a pretty big guy, usually (laughs)! Just common sense.

But it was great, because at that time, for two bucks you could get in and see Muddy Waters or Howlin’ Wolf, Otis Rush, Junior Wells, Buddy Guy. Any night of the week, there was somebody great playing somewhere. Because blues at that time was like rap is now; it was the living music of choice of the black people.

People don’t realize how big the Chicago blues scene was. There were way over a hundred clubs that had known people; I’m not kidding. You’d get in with a bunch of guys, and you had two or three favorite clubs you liked to go to. My places were Pepper’s Lounge, Teresa’s, and the Blue Flame.

At Pepper’s, they would usually have Muddy Waters on the weekends, and in between they’d have people like Detroit Junior or Little Mack. At the Blue Flame, there was Junior or Earl Hooker. And Teresa’s was Buddy Guy.

It’s one thing to get to witness those artists, but did you have to buck up your courage before you let people know you played, and would get to sit in?

Oh, no. That’s the first thing I’d tell them. I tried to meet the musicians, and it was amazing how nice they were. They’d invite me over to their houses. What took nerve was going over to the house, because it was usually in a bad neighborhood. But Otis Rush immediately said, “Come on over. We’ll work on some stuff.” Sammy Lawhorn was real nice to me. What a beautiful guy, what an amazing player. Sammy got me a gig subbing for him with Junior.

In those days, you played from 9:00 ’til 4:00 every night of the week, and then 9 to 5 on Saturdays. And they expected 45 on and 15 off most of the time. And it didn’t pay much. If you were making $11 and someone offered you $12, you were gone. I was playing with [saxophonist] J.T. Brown, and then I got the job playing with Hound Dog Taylor, because he was paying a dollar a night more.

The Chicago blues scene was a great place for developing musically, because I don’t care how green you were and how famous that guy was, by 1:00 or 2:00 in the morning he was glad to see anybody come and sit in. Take a little rest, have some drinks, bulls**t with the chicks – so you got to sit in a lot. And if you were going to go someplace, and you knew you were going to sit in with, say, Little Mack, you’d sit down and learn three or four of his tunes anyway – so you wouldn’t make an ass of yourself. You were sitting in with somebody every night of the week, so you’d learn a lot of tunes. Because sitting in was not just sitting in; it was kind of a little lightweight audition, too. You might end up with a gig. It was a great apprenticeship.

At that stage, were any other white guys playing in the blues clubs?

There were no white guys playing any blues gig until the Butterfield Blues Band, as far as I know. That was being at the right place at the right time. There was this beautiful thing called the blues, and a few hundred million white people, and they’d never basically met to any extent. When the window of opportunity opened, we were lucky to be there and be able to deliver it. We weren’t as good as Muddy Waters or Howlin’ Wolf, but we were evidently good enough to at least get people to think of where it came from.

Blues was trying to creep in around the edges through the folk festivals. They’d always have somebody like Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee or Leadbelly before that. But that was going to be a slow process, because they just had one token guy at every folk festival. It wasn’t balls-out blues.

Besides the window of opportunity, you guys had some other quality or energy. Because it wasn’t that foreign from rock and roll.

That was one of the great things about that band and why it was a great apprenticeship for me. You had high standards of how hard you had to hit it, and not taking “no” for an answer, just bringing 100 percent all the time. From the get-go, that was the m.o. in that band.

In 2000, you made a great live CD, That’s My Partner, with another mentor, Little Smoky Smothers.

Little Smoky was real slick and modern when I first met him. He was playing at the Blue Flame, and he had a pompadour and five horns. He was the only guy in Chicago who could play “Don’t Throw Your Love On Me So Strong” exactly like Albert King. He could figure out anything – make “Frosty” sound just like Albert Collins.

Who specifically would you consider your main guitar influences?

My influences started earlier than Chicago. I really liked Lightnin’ Hopkins and John Lee Hooker. Especially for me not having much of a musical background, one guy with a guitar was good for my ear. It also caused me problems when I started playing with bands, because I didn’t know about changes. Listening to Lightnin’ Hopkins – 14 bars, 19 bars, what the hell?

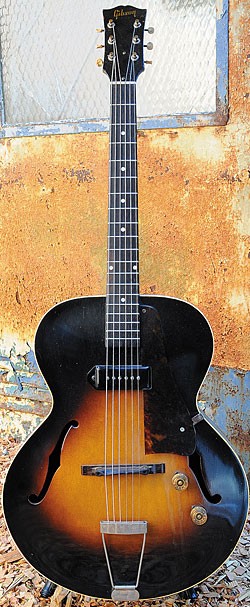

Gibson ES-125. Photos: Preston Gratiot.

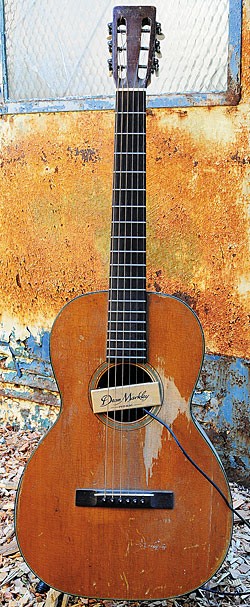

Bishop’s very worn ’61 Martin 0-16NY has cracks in its top and sides, and a Dean Markley Woodie Pro Mag pickup. “It’s got a nice sound,” he says of it. “I’ve used it on a couple of records for country blues stuff.”

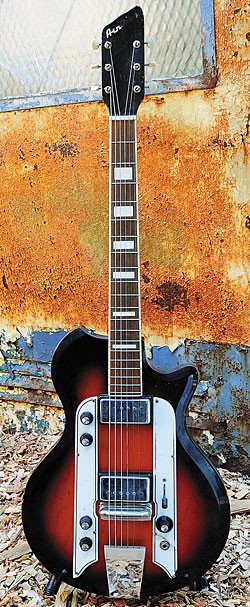

Bishop admits this Airline is not a very good guitar, but says, “I bought it because it looked like something I’d seen Earl Hooker play.”

I bought their records in Tulsa. See, for eight cents apiece you’d get the old records off the jukeboxes after they’d had their run. Lightnin’ had “Mojo Hand,” and John Lee always had something going.

What about Jimmy Reed? He kind of crossed over.

Oh yeah. People didn’t even know that was blues. Him and Fats Domino – and Jimmy Reed was actually more blues.

Who were your slide influences?

I only have one slide influence, and that’s Earl Hooker. The drawback of most of the slide styles I heard was that you had to re-tune the guitar, which is kind of a trap. All the guys who played in E tended to sound like Elmore James; guys who played in G tended to sound like Robert Johnson or Howlin’ Wolf. I think tuning has ruined as many guitar players as Charlie Parker did saxophone players or Little Walter did harmonica players. The thing’s just so attractive, a lot of guys just never got past it.

The reason I loved Earl Hooker, number one, was that he could just sound like a bird singing. He was a natural genius with a beautiful touch. He could play up past the frets as in tune as he did down low. I liked that he used the slide on his little finger, which left three fingers to play pieces of chords and little runs and stuff. If you think about it, that’s more than Django Reinhardt had.

When I started out, nobody had more than one guitar anyway; there was no such thing as a guitar tech to tune it for you; and there weren’t even any tuners. The good thing about [playing slide in standard tuning] is it forces you to find your own melodies, and not just fall into patterns you heard on records. Earl Hooker was a good influence in the respect that he’d play vocal lines, like a singer.

Also, a lot of guys play with the slide on their ring finger, which is easier because you’ve got your other fingers around it. The slide on the little finger is a little bit harder, because out there by itself you’ve got to exert some control. But it leaves the other three fingers open to play.

But Earl Hooker, man, is a guy who doesn’t get the recognition that he should. I think the reason is his best playing never got on records. I’ve seen him in person when it was like seeing a great preacher. People were just electrified; everybody on their feet hollering. He was so respected among the musicians, you could ask anyone – even B.B. King – who was the greatest guitar player? They’d tell you Earl Hooker. He could go to any club in Chicago, and he didn’t even have to ask if he could sit in – just go up on stage, tap the guy on his shoulder; he’d give him the guitar, and Earl would go for it.

You didn’t play much slide in the Butterfield band.

I wasn’t that good at it yet. I didn’t get serious about it until later. I’m thinking about doing a slide CD for the next one.

What type of slide do you use?

It’s [very light] copper pipe. A buddy of mine gets 10-foot lengths and cuts it up and smoothes off the edges and roughs up the surface a little, so you get that kind of whistling sound. It’s a sound I don’t think I’ve heard anybody else get on slide.

After Butterfield, did you meet other white guys who were into blues?

I met Bloomfield at a pawnshop on the North Side. He was behind the counter. It was his uncle’s pawnshop, and he worked there. First time I met him, I asked him to hand me a guitar, and I played a couple of blues licks. “Oh, you like blues, huh?” I said, “Yeah.” “Like this?” And he played rings around the world!

What kind of guitar did you have when you were first sitting in around town?

I don’t remember what I had first, but at one point I had an SG. Then I had a Telecaster, but I wasn’t doing too good. I kept breaking strings. One time we were playing some Bo Diddley tune, and I broke three strings with one stroke. And Louis Myers came in, and I said, “I’m breaking strings with this damn guitar; there’s something wrong with it.” He said, “There’s nothing wrong with that guitar; you’re just green.” I said, “I bet if you played this guitar, you’d break strings on it, too.” He said, “I would not.” He had this 345, so I said, “Well, let’s just trade. We’ll see.” We’d both been drinking a little bit, so he said, “Alright.” He takes the Tele, and I take his 345. I played the 345 for a week and just fell in love with it. It suited me. I could get it to ring and sustain like I couldn’t with the Telecaster. He came back and said, “Let’s trade back.” I said, “Mmm… no. Why? Are you having problems?” He said, “Every time I hit the damn thing, a string breaks” (laughs). But shame on me; I didn’t trade back. I’ve been playing 345s ever since.

When did you acquire Red Dog?

I don’t remember. Right then, I started playing the oldest one I could find – and that was about ’62 maybe when that happened. My saying used to be that every five years either the airlines busted it or the thieves would get it. That went on for three or four guitars; then finally this one was just a stroke of luck.

Did the formation of the Butterfield band start with you and Paul?

I don’t remember. I think there were two or three false starts; then it finally got to be me and Paul and, out of Howlin’ Wolf’s band, Jerome Arnold and Sammy Lay. The four of us played together for a couple of years. We played several years before we put out that record. Probably around ’62. We played six nights a week, six or seven shows a night.

Was that at Big John’s?

Exactly. Some vulnerable club owner decided to take a chance, I guess. The place was packed every night. Little Walter came up there and jammed with us; all kinds of people did.

What was your learning curve like once you got around the scene in Chicago?

I went in for it 24 hours. See, the University of Chicago was a place where you didn’t have to go to classes as long as you could pass the test. So I’d just stay in the ghetto for weeks at a time, come back two or three days before the semester ended, and study up.

It went quick and was a great apprenticeship, because if you’re playing six or seven shows a night, six nights a week, for two years straight, if you don’t get good, shame on you.

Who joined first – Bloomfield or Naftalin?

They both got put in there by the producer when we went to make the record. You can hear the band before Bloomfield in some of those collections they put out, like What’s Shakin’. After they played on the record, he stayed in the band.

How did you feel about that? Did you have to move to rhythm?

I was already playing rhythm pretty much. I was pretty green. I never really had much resentment about it. It was a great learning experience.

Bloomfield was an interesting, amazing guy. Real brash and out-front and hyper. A little too much for his own good, as it turned out. But he was a funny guy, man. He said, “I never brush my teeth, because it builds up a protective coating to keep the germs off my teeth.” I actually saw him go on a plane and look around and say, “These people are ****ing losers! This plane is going down!” And he’d turn around and leave (laughs).

Here’s something most people don’t know. Sometimes, during “East-West,” Bloomfield would do a fire-eating act. He’d have one of these mallets that look like they play kettle drums with. He’d put lighter fluid on it and light it up. He’d play some of that exotic sounding stuff, and there’d be all these hippies on acid at the old Fillmore, and he’d break it down to just the bass and drums. He’d get the thing out and make a big show; sling his guitar behind his back and put his head back and eat fire.

He said the secret was, “Don’t ever inhale.”

Was the jazzier, exotic stuff a natural thing for you to adapt to – playing freer and going outside pentatonic scales?

I think between the first and second albums, Bloomfield had an influence on the rest of us. He was into Ravi Shankar and Ornette Coleman and Archie Shepp and people like that. He kind of exposed us to that, and then again I think we had found out about acid in the interim.

The RedPlate III Charm Elvin Bishop Special is part of the company’s TweedyBird line. Photos: Preston Gratiot.

The RedPlate III back.

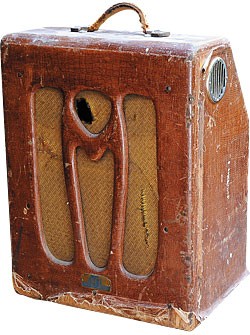

This Magnatone Troubadour is “so old it’s got a microphone input.”.

Magnatone Troubadour back.

Is it true that you played with the guys who became the Art Ensemble Of Chicago?

Yeah. Phillip Wilson, who later became our drummer, was with those guys, and Lester Bowie. I made one record with them – actually a single that Nick Gravenites made. But we used to get together and socialize and have jam sessions – just crazy, some of them. I remember during one jam session Roscoe Mitchell, a little short dude, had to stand on two phone books to play the bass saxophone, and I had my head under a bucket and was talking with the King Of The Crawdads (laughs).

Did Bloomfield play a Telecaster on the first Butterfield, like he’s pictured with in the liner notes?

Yes. And later he got into a Les Paul because Freddie King played one. When I think back to the sound of East-West, it doesn’t sound like a Tele.

When Bloomfield left the band and formed Electric Flag, you guys recorded The Resurrection Of Pigboy Crabshaw, both with horns.

We all loved soul music, and horns were happening in soul music. People sometimes confuse me and Bloomfield with starting the twin guitar thing, but actually whenever I did that with Bloomfield we were trying to do horn parts. We liked horns before we ever had any horns; we tried to kind of take the place of them.

Did you two work out who would play what, or was it just instinctive?

We sort of had a way of naturally complementing each other, and then if there was something wrong, we’d stop and fix it.

Why did you decide to quit the band?

Well, whenever you’re a so-called sideman, and you get to do two or three songs a night that are really close to your heart, the thought can’t help but pop up in your mind, “What if I got to do all the songs I wanted to do?” It’s a judgment call; do you think you’re actually able to do that?

Is that when you moved to San Francisco?

Half of Chicago moved to the West Coast in 1968, when Bill Graham started booking and cracked it open where you could get crossover gigs. Before that, it was never possible. And they got out here and found out they didn’t have what they called The Hawk here – that wind that cut you to the bone in Chicago in the winter time. And you didn’t have to watch your back; it wasn’t dangerous; the ladies were cooperative – so there was just nothing like it.

During the blues revival, certain bands had an almost academic approach. You always ensured that there was some entertainment in there, too.

Yeah. It was just a natural tendency to want to get over with the people. An extreme example like Miles Davis playing with his back to the people – I never had any part of that in my personality. Number one, I always liked guys who had a strong desire to communicate with people, and, number two, I’m pretty realistic about my limitations. I always listened to songwriters who had a strong message. I knew I didn’t have a voice that was beautiful in itself, so I had to have a story to capture your imagination.

You got lumped in with the Southern rock movement, but were also part of the Bay Area scene. Did you have an affinity with Capricorn and the other bands on the label?

Well, that happened because we played quite a few gigs on the road with the Allman Brothers Band, who were coming up pretty strong then. I got to be friends with Duane and Dickey, and after some party in San Francisco Dickey grabbed me and [label head] Phil Walden and made me play a few songs for him. He signed me the next day.

It was lucky for me, because the so-called Southern rock sound, I think that’s the only time I had an officially sanctioned media cubbyhole they could stuff me in to.

I want to put in a word for my favorite living slide player, Derek Trucks. He’s very famous and successful, but he doesn’t get the respect he should. You have to be a slide guitar player to know how difficult it is to play that fast and that tasty and that in-tune.

One of my pet peeves is that a lot of writers and media people don’t like to think. They’re much happier if they can find a five-word description they can stick you in. Then they don’t have think, “What is he really about?” It’s too tempting to say he’s the new Duane Allman. He’s a lot more.

The main thing I like about Derek is the notes he chooses and his phrasing remind me of gospel music. That’s the main influence I see. Real good gospel music.

Warren Haynes is a great player, too. He was nice enough to come and play on this CD on his day off after playing the Fillmore. He told me to rent a Tone Tubby. That’s the only thing he plays through. This just goes to show how much sound a guy carries around in his hands. The Tone Tubby didn’t quite get what he wanted out of it. He heard this Vibrolux and said, “Let me try that.” So my slide solo and his slide solo, which are the two most different-sounding things in the world, were both through that amp.

During the Southern rock period, did you still think of yourself as a blues guitarist?

Well, like the kids say today, it is what it is; it’s all good. Southern rock now sounds like the Grateful Dead. Jam bands.

Did you ever get to play with Jimi Hendrix?

Yeah, three or four times in New York. We used to go to all different places. Somebody found this picture on the internet and sent it to me; I don’t remember where it was. (Ed. Note: Elvin leads the way to an enlargement on the studio wall of him playing and singing in front of a microphone, with Hendrix behind him, playing an Epiphone Wilshire.) I used to jam everywhere. It was more of a jamming time.

When you signed with Alligator, was the idea to get back to your blues roots?

That’s kind of what I felt like doing, but I think it might have been a misguided effort on their part to get some kind of a rock star on the label. I don’t know. I just got where I wanted to make a record. For a long time, I was just having fun – too much fun, you know. About 20 years ago I quit drinking. Then I thought, “Damn, I haven’t made a record in a while. Get my ass in gear here.”

For the new CD, did the label come up with the concept of having the various guests?

There wasn’t any label. I did it on my own dime. I got to thinking about how great the guys treated me and how lucky I was to have met Hound Dog and Junior Wells and Butterfield, Clifton Chenier, Big Joe Williams, Fred McDowell – guys like that – early in my career. They all helped me out. And I thought about the young guys coming up now, and it kind of put my mind on how the music flows from one generation to another.

I got most of the tunes from the old guys, and wanted to get the younger guys in to play on them. Like “Yonder’s Wall” – the first time I heard it, it was by Elmore James. Now someone tells me it originally came from World War II, by Arthur Crudup. And then Butterfield did it during the Vietnam War, and now I got Ronnie Baker Brooks to do it in this war. “Your man went to the war; I know that it was rough. I don’t know how many men he killed; I know he killed enough.” They’re all singing about different wars. That’s The Blues Rolls On.

But it turned out way better than I could have hoped. I know the CD business is going into the dumper, and this is probably the ideal wrong time to do one – it might just be money down the drain – but I said, “I don’t care; I’ll have some great music to put out there.”

Most all-star projects, to me, aren’t very good. You see all these great names, and you take it home, and it’s, “Aw, it doesn’t sound like he felt that one.” Or they didn’t match up the material with the guy very well. I tried to avoid all that in front by thinking as hard as I could about what material would really suit the guy, so he’d be interested and really put his heart into it. I was lucky to come up with stuff that pretty much fit the description all the way around.

Ampeg Reverbrocket R-12R with serial number 005204. Photos: Preston Gratiot.

This silverface Fender Vibrolux is Elvin’s primary studio amp.

For instance, the George Thorogood one. I always thought of George as something kind of like Hound Dog, because he’s the type of guy who’ll sit up there and what he’s playing musically is just wrong as a football bat, but he makes people like it. It feels good; he just goes for it – just like Hound Dog. So I picked out this Hound Dog tune and asked George if he’d like to do it, and he said, “Yeah, I used to open for Hound Dog all the time in my early days.”

How did you get that really raw sound on the solo tune “Oklahoma”?

Guys are always asking me that. I used one of the replica 345s that had a real bad buzz on the A string. And the speaker was starting to go out on the Vibrolux. I thought, “I’ll never get that sound again. I better do something before the speakers go all the way out.”

And I got lucky. I used to hang out with John Lee [Hooker] a lot, and looked at the shoes he had, and he had on the kind you wear with a suit, you know – hard leather heels. I bought a pair of those and took them to the shoe shop and got some taps put on, and I stuck a microphone right under there (motions to the plywood riser on which his amps rest in his studio).

Your sound has always had that heavy, percussive attack.

I’m trying to give the people their money’s worth [laughs]! I use the Varitone switch, which is a glorified tone control with a little more to it than that, because I’ve got a heavy touch. So when I go to chopping chords, I turn the Varitone to the left a little bit, to brighten up the sound. It doesn’t distort as much. But then when I play slide, I want it to get as fat and thick as I can, so I turn it all the way the other way.

You’ve got several 345s.

Most of them are probably not the least bit interesting. I’m not a collector. All the other 345s represent trying to sound as good as my main ’59, Red Dog. Which I’ve given up on now; I’m just looking for one that I don’t hate that bad, that I can take on the road. I’ve tried to retire Red Dog from the road.

What’s so special about it?

It must be a great piece of wood. I’ve had it for so long, I don’t know if it suits my style or if I molded my style around it.

I got the sunburst one in Austin, at One World Music, and the owner couldn’t tell me where it came from. The provenance was in question. I don’t know what year it is.

Two of them are attempts to duplicate Red Dog. I met Henry Juszkiewicz at Gibson, and he said, “You’ve been playing Gibsons a long time. Is there something we can do for you?” I said, “Yeah. I’ve got this ’59, and I don’t like taking it on the road, but I can’t find anything that’s close to it.” He said, “Well, we can make you one just like it. We’ll get out the ’59 plans and have the Custom Shop make you one.” They sent it to me, and it was something that would be better for Chet Atkins – so clean it scares you. Totally even output all the way across. It’s a great guitar, but it doesn’t sound anything like my original.

So next time I saw him, he said, “How’s the guitar?” I said, “It’s a great guitar, but it really isn’t anything like the one I’ve got.” So he said, “Well, send that one to our shop, and we’ll measure it and take it apart and check the wiring and everything. We’ll make you one.”

I FedEx’ed to them, and they did all that and FedEx’ed it back. A couple of months later, I got the copy. And it’s a little closer, but not remotely like mine. Finally someone copped to it and said, “Well, we can’t really make one like that.” When they moved from the plant in Kalamazoo to Nashville, they left behind a bunch of parts. Also, all the rosewood is approximate. This is 1959. And then there’s always the magical difference of just that one piece of wood.

Is the non-cutaway an ES-125?

I don’t know. I had one of these second-choice 345s that had gotten stolen. I found out through the grapevine that this junkie who lived down the street was reputed to have it. So I went down to his house and just kind of barged in – “Where’s my guitar?” He came up with some junkie explanation. I saw that one sitting over there and figured, “That’s all I’m ever gonna get out of this.”

What type of amp is the one with your name on it?

That’s from a guy in Phoenix named Henry Heistand, who I met on the blues cruise. He makes amps called RedPlate. It’s called the III Charm. He made two of them before that didn’t butter the biscuit; we just kind of narrowed it down. I told him I wanted something without master volume and presence and all that.

The track on the new CD with you and B.B. King is very special.

I remember the first time I met him; it was at the old Fillmore. Bill Graham would put bills together that were like Butterfield, B.B., and Cream. I was sitting at a table upstairs in the back, and Eric Clapton’s sitting in one chair, I was sitting in the next one, and B.B.’s sitting in the next one. And then there was some way-out acid casualty sitting next to B.B., just talking all out of his head. So here’s one dude with an Oklahoma accent, a dude with a British accent, and B.B.’s sitting there just making sense of the whole thing. I said, “Man, if the Martians ever land, I want B.B. to do our talking for us.”

I’ll tell you great story. This actually happened. I cut the track that B.B. played on here in my studio and then flew to Las Vegas for him to cut his part. And, see, B.B. likes my jam and my hot sauce. When I was getting ready to leave, I asked him, “You want the jam or the hot sauce?” He said, “Both.”

So I was at the Oakland Airport, getting ready to go through security, and the guy fishes around in my bag and says, “Is this homemade jam?” “Yeah.” He said, “It looks delicious. Is it good?” I said, “Well, they tell me it’s pretty tasty.” He said, “That’s too bad, because you can’t take it through,” and he stuck it under his chair – instead of how they usually throw it in some bin. He was a middle-aged black guy with a name tag that said “Eldon.” I said, “Y’all know who B.B. is. Could you just give me a break this one time? It’s for B.B. King. He loves my jam, and we’re doing a session. I’d really appreciate it.”

He said, “Well, you tell B.B. King that the thrill is gone, and so is his jam!” (laughs).

Has the economy had much effect on what it’s like on the road?

It’s had a huge effect on the young guys coming up. I feel sorry for them. There’s practically no clubs left to play, and I can’t visualize trying to hook up between the weekends, trying to connect. It’s awfully rough. I’m lucky to have a foot in the door.

I pretty much fly back and forth on weekends. I play all over the place, so I’m doing alright. I don’t know; I think the process of going from has-been to legend has kind of been accomplished. Now it’s straight up (laughs)!

This article originally appeared in VG‘s February 2009 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Elvin Bishop