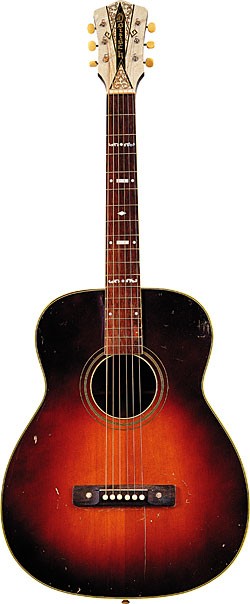

1986 Schecter Yngwie Malmsteen

For most of the 1970s I didn’t listen to or play electric guitar music of any kind, only acoustic music. I did, on occasion, read about it. Then, in 1981, I decided I needed to ride a stationary bicycle. The only way I could do it was to listen to music for distraction. I’d read about a young hotshot guitar player named Randy Rhoads, so I bought Ozzy Osbourne’s Blizzard of Ozz on cassette to audition during my ride. Talk about aerobic exercise! That kid could play! This ignited an ironic interest in the then nascent heavy metal revival. Inevitably, this led to hearing the young Swedish phenom Yngwie Malmsteen.

Malmsteen was born in Stockholm and reportedly became obsessed with the guitar after seeing a news report of the death of Jimi Hendrix. Besides the usual rock heroes, Malmsteen also fell under the spell of the 19th century Italian virtuoso violinist and guitarist Niccolo Paganini, which had a major effect on his style. Much of Malmsteen’s playing consists of extended scalar excursions at an unrelenting velocity. There was no denying he was good, too. Rhoads and Malmsteen are often thought to be among the founders of the “neo-classical heavy metal” school. After playing one session with a band called Steeler, Malmsteen joined, Alcatrazz, then went solo in 1984. By ’88 he was popular enough to warrant his own signature model Fender Stratocaster. But it wasn’t his first namesake guitar; perhaps far more interesting was this 1986 Schecter YM-1 Yngwie Malmsteen.

Schecter Guitar Research was founded in 1976 by David Schecter in Van Nuys, California. The company began as a repair shop and graduated to making replacement necks, bodies, pickup assemblies, bridges, and other parts, basically everything needed to build a custom guitar, which was a popular concept in the mid ’70s.

Schecter offered things the big manufacturers just didn’t offer at the time, like fancy woods and nifty electronics. For a brief while, Schecter was also affiliated with Wayne Charvel and provided parts to other manufacturers.

Circa 1979, Schecter began producing finished guitars under its own brand name. Despite having very limited distribution, they met with some success thanks in part to having Pete Townshend play one of their single-cut guitars, followed by Mark Knopfler.

As a result, the company faced either becoming a full production manufacturer or selling to someone with more resources. In ’83, it was sold to investors in Dallas who turned Schecter into a full-scale production house, sans most of its California employees. Production guitars are never as good as customs, so the brand suffered, at least in the eyes of hardcore enthusiasts. Still, it managed to make interesting guitars during the sojourn. In ’86, Schecter scored its first big-name endorser in the person of Yngwie Malmsteen! It built a couple of custom guitars for him with contoured offset-double-cut bodies, scalloped fingerboards, and reverse headstocks (a similar model without the scalloping was promoted at the time as a Jimi Hendrix model).

The YM-1 Yngwie Malmsteen may or may not have been a limited production model, but it certainly wasn’t mass-produced! The one shown here originally went to Troubadour Music, then of King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, where it was bought as new old stock after years sitting in the back room.

It has a figured ash body with a translucent butterscotch finish. The bolt-on neck is maple, with a regular (tuners on top) headstock instead of the reverse models made for Yngwie. It has gold Schaller tuners and a Schecter/Wilkerson knife-edge floating non-locking vibrato system. If you like feather touch in your vibrato, you’ll like this. If you play with a really light touch, the scallops aren’t too bad, but if you’re accustomed to touching a meaty fingerboard, you wouldn’t like this. It’s very easy to screw up the intonation by pressing too hard.

Even though this is not a California Schecter, it has an unbelievable powertrain; the pickups are three high-output Schecter single-coils with a “Phantom” system. Yngwie usually played a Stratocaster with the middle single-coil and tone control disconnected. With the Phantom arrangement, the middle pickup serves as the silent second coil in a humbucking arrangement. The front and back pickups are controlled by a three-way select. But what’s really cool is that all three tones are distinctive and feature that funky out-of-phase sound of the in-between positions on a Strat. Unlike Malmsteen’s preference for no Tone control, this guitar has a Volume and individual Bass and Treble controls, which give considerable flexibility in sound.

While some tend to disparage production Schecters of this period, there’s nothing not to like about this guitar!

Schecter actually introduced a few other interesting models during this period, including the Illusion, with see-through cutouts based on a design by Bill Reed.

In ’87, Schecter Guitar Research was purchased by Hisatake Shibuya, owner of ESP Guitars and the Musicians Institute in Hollywood. Schecter moved back to California and for a decade once again became primarily a custom operation. In ’98, Schecter introduced what would become its main offering – a line of guitars made in South Korea. The company, which for many years was known mainly for Fender-style guitars, increasingly shifted to exotic shapes in a BC Rich mode, for which it is primarily known today.

Whether this Schecter Yngwie Malmsteen is a rare bird or not is unknown. But it is far off the radar. One thing for sure is that it’s a really fine guitar, whether you want to shred like Yngwie or lay out one note like B.B… as long as you can deal with the scalloped fingerboard, that is.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s March 2008 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.