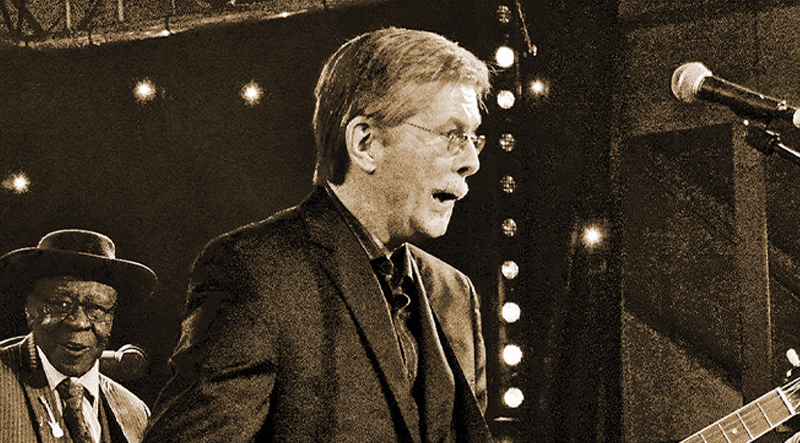

The phrase “electric blues” is a catch-all for many genres, but for aficionados it refers to a highly specific idiom from the Windy City. In fact, if you listen to Billy Flynn’s smokin’ new album, Lonesome Highway, you will identify it instantly, as his tone and sweet licks capture the nuance of Chicago’s best guitarmen. For Flynn, this kind of blues is less about chops, and far more about tone, soul, and the very deepest of grooves.

The phrase “electric blues” is a catch-all for many genres, but for aficionados it refers to a highly specific idiom from the Windy City. In fact, if you listen to Billy Flynn’s smokin’ new album, Lonesome Highway, you will identify it instantly, as his tone and sweet licks capture the nuance of Chicago’s best guitarmen. For Flynn, this kind of blues is less about chops, and far more about tone, soul, and the very deepest of grooves.

Who are your main influences?

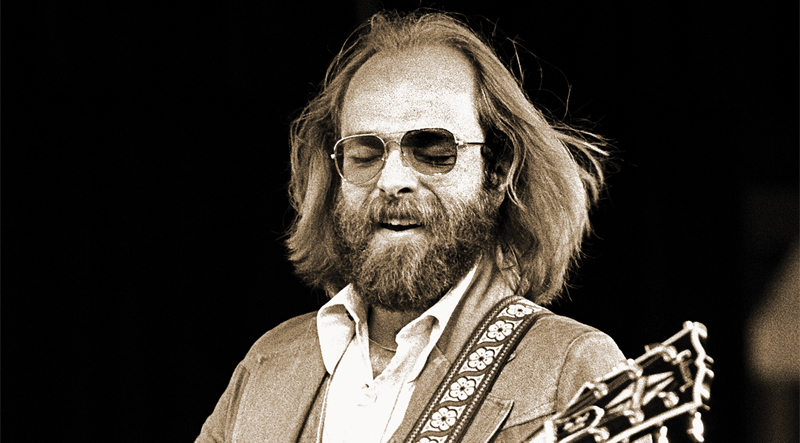

B.B. King and Muddy Waters, but also Chicago’s West Side blues players like Magic Sam and Otis Rush. For slide, it’s Tampa Red, Robert Nighthawk, Earl Hooker, and Elmore James. My number one influence was Jimmy Dawkins; after seeing him play, I knew I wanted to play in the style that he created.

The album’s opener, “Good Navigator,” has a feel and tone like Chuck Berry. You really nailed it.

I bought my first electric guitar when I was about 12 and spent a lot of time playing along to his records. I used to watch him on TV, and he said he listened to Elmore James, T-Bone Walker, and Charlie Christian. Because of those guitarists, I thought of Chuck Berry as more of a Swing-era player from the ’40s and ’50s rather than a rock and roller. He had a real ringing tone.

“Small Town” displays some blues-funk bottleneck.

That sound was from Earl Hooker. When I was learning to play, I bought every album I could by Earl, and when I saw pictures of him, I noticed a small slide on his fingers. Now I use that small slide, too. It’s good for single-note runs.

Your tone on Lonesome Highway is huge. Is there any secret to getting a big, fat tone?

I try different things, like changing pickup positions and adding reverb or using different Tone-control settings. Where you pick on the guitar changes the sound, too. Also, when I used to play alongside bluesmen like James Wheeler, Louis Myers, and Little Smokey Smothers, I had to find a way to step up my rig and become aware of the things I needed to do to keep up.

Is the dirty tone on “If It Was For The Blues” from the amp, or did you use a booster pedal?

No overdrive pedal was used; we used a Fender Super Reverb and an original Peavey Bandit turned up loud! I hooked them up together, but miked each separately.

What guitars and pedals did you use?

I used a 1994 Gibson ES-335, a Squier Vintage-Modified Jaguar for some rhythm, and a Squier Strat. All guitars are stock. I had a Cry Baby Wah I’ve used since the ’70s. For gigs, I play Jay Turser semi-hollowbodies because they’re very light, play great, and are sturdy. I’ve taken them around the world and never had a malfunction.

What kept you on an old-school blues path instead of playing louder blues-rock?

I’ve always loved the true sound of the blues and was inspired by the blues greats. I also loved the rock and roll of the ’50s and early ’60s, but never really was a rock musician myself. I was much more into jazz and early rock with a swinging rhythm section. By meeting – and being encouraged by – many great Chicago players like Johnny Littlejohn, Jimmy Rogers, Mighty Joe Young, and Luther Allison, I knew I wanted to play blues. They sounded different than everyone else to me – that real Chicago sound.

Your career started in the ’70s, when vintage blues was not much in fashion. Did that shape you as a blues musician?

During that time, I had the pleasure of meeting B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, Charlie Musselwhite, Jimmy Dawkins, Jimmy Rogers, and Luther Allison, and many others. To me, there was never a lack of blues, and there was so much of it – there were lots of musicians touring and playing in a lot of venues. Later, I also played Top 40, disco, and country to keep busy and working. Playing all that stuff helped me develop as a musician and, actually, the blues also was being influenced by funk and disco at the time.

What advice would give a young player who wants to learn more about traditional blues guitar?

My advice would be to practice, listen to the original electric-blues artists, and not assume that blues is easy to play. There are some basic elements of the music that are sometimes overlooked, but give it that great sound. Once you’ve got the building blocks, you can develop your own style. Listen to lots of music and keep your ears open to new styles.

This article originally appeared in VG October 2017 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Do you have a particular favorite solo on Lay It on Down?

Do you have a particular favorite solo on Lay It on Down?