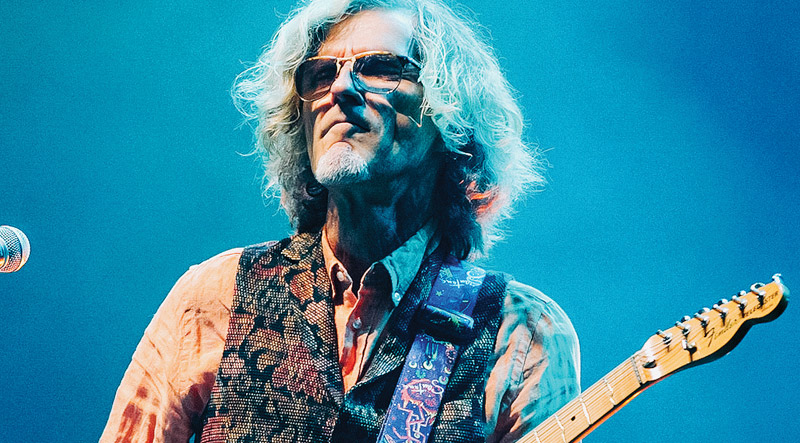

Thirty years into a stellar career, progressive-rock wizard Roine Stolt can be heard on the latest – and perhaps final – work from Transatlantic, a supergroup featuring past and present members of Marillion, Spock’s Beard, Dream Theater, Winery Dogs, the Steve Hackett Band, and his own Flower Kings. Titled The Final Flight: Live at L’Olympia, this three-hour live album captures a Paris date brimming with tone-packed solos from the Swede. But is this really the end of Transatlantic? Stolt gave VG the final scoop.

When the first Transatlantic album came out in 2000, it was seen as a side project from four established proggers. Yet here we are, decades later.

I personally thought it might be a one-off, just a fun collaboration for one album. Really, I’m always open to working with new people and knew [Spock’s Beard singer/keyboardist] Neal Morse already. I did not know much about Marillion – and had not heard Dream Theater. So as we got into recording, I at least thought we could get some attention because we were a so-called supergroup.

Transatlantic is known for playing long, complex suites. Are the live parts all worked out in advance?

I would say that 90 percent is worked out, but of course with very few days of rehearsals, some of the keyboard and guitar parts remain a bit loose. I was surprised in the beginning 20 years ago, when fans went online and said, “Roine doesn’t know his own solos.” I could not understand, but finally it dawned on me that these fans expected the exact same solo each time (laughs)! I grew up on Duane Allman, Jimi Hendrix, Allan Holdsworth, and Frank Zappa, who all played solos differently each night.

On this tour, the band played more than three hours onstage. That’s a lot of music to remember.

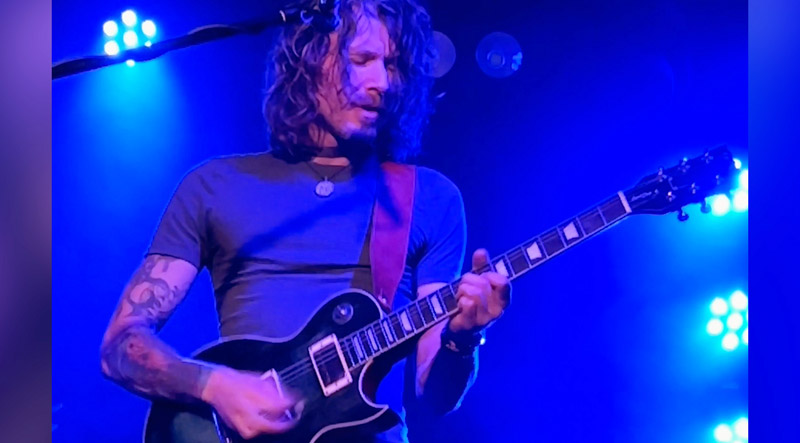

It was quite a tall order and I had to rehearse a lot, but still you don’t know exactly what to play. We all live far away from each other, so we can’t regularly interact or suggest parts. In hindsight, I think guitar parts could have been mapped out better between me and [stage guitarist] Ted Leonard.

Do you ever make mistakes onstage?

Of course, I hear errors and out-of-tune things in our live recordings. To get a full band in-tune for a long show is not easy, as we have no background tapes – we play it all live. Fortunately, fans still have a wonderful night with their favorite band onstage. They enjoy the diverse sounds and sections, the lights, the smoke, the poses – but perhaps I’ll hear the bum notes, tuning stuff, variations, or wrong tempos. But again, you’ve got to remember you play for the audience. If they love it, it is good. The gig at L’Olympia wasn’t perfect, but the fans were outstanding – a lovely Paris audience.

Your tone keeps getting better and better. What’s in your gear toolbox?

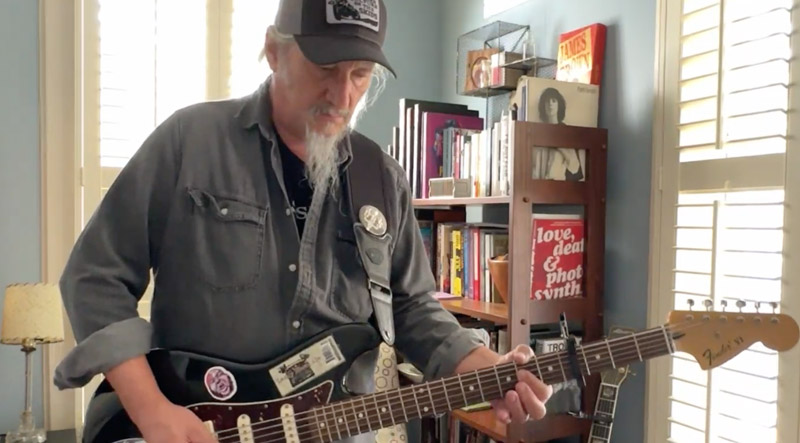

For recording, it changes day to day depending on whatever I have set up in my studio. Most of it sounds good if you tweak it a bit. I usually have the Orange TH30 head or Mesa-Boogie Transatlantic head with a 2×12 Orange cab with vintage speakers or a small 1×12 closed Orange. For cleaner tones, sometimes a Fender Vibrolux.

For guitars I’d use mostly my Mexico-built Fender Telecaster Thinline with a 24-fret True Temperament fretboard, piezo, and Seymour Duncan mini-humbucker in the neck; I’ve had it for 20 years, and it’s perfect. Sometimes, I’ll grab an ES-335 or my ’53 Les Paul goldtop. Acoustics are Guild Jumbo or a Seagull 12-string that sounds great for recording.

Which pedals are essential to your Transatlantic rig?

For that tour I had a really small pedalboard because we were flying a lot. I had a Dunlop volume pedal, Cry Baby 95Q wah, Keeley distortion/compressor, TC Electronic Nova system for delay, phaser, overdrive, and tremolo, Tech 21 Acoustic DI line box, and Vovox cables. The amps I played live were mostly a pair of Orange TH100 heads with two 4×12 cabinets.

Does “The Final Flight” mean you are closing the book on Transatlantic?

Well, I’m not the right person to ask – and never say never – but in some strange way, Transatlantic has made its point. Not sure we can be productive as a unit without repeating ourselves too much. I personally look forward to other new collaborations; recently, I did a fabulous recording with drummer Doane Perry of Jethro Tull, keyboardist Vince DiCola, bassist Tony Levin, and some other great players. I’m waiting for that to get finished – it’s just one of the best recordings I’ve been on in my many years. So, if this is our last Transatlantic album, at least the Paris show will be a very fine goodbye. Transatlantic has been a wealth of ideas and very strong wills – we have great creativity. I will always treasure that.

This article originally appeared in VG’s May 2023 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.