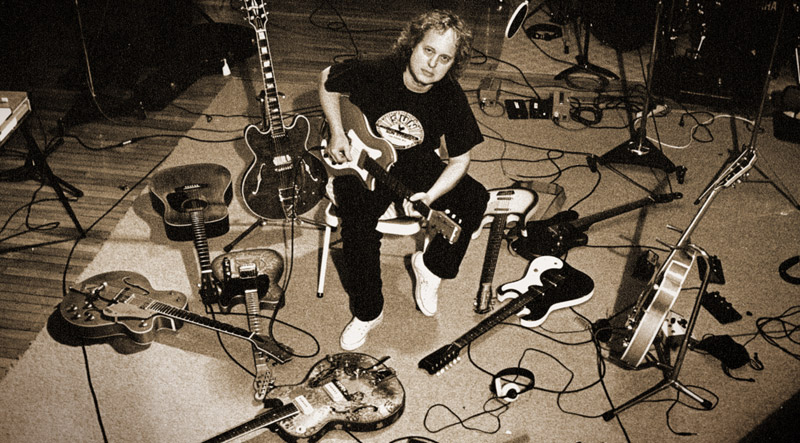

Ed. Note: Guitarist/producer/recording artist/guitar innovator (we could add more to that list!) Steve Ripley has passed away (January 3, 2019) at his home in Pawnee, Oklahoma after battling cancer. He was 69 (1950-20019). Most guitar players first became familiar with Ripley from the 1980s Kramer-Ripley Stereo Guitar, with a pickup where each of the six polepieces had its own control knob. Ripley was the guitarist in The Tractors, whose self-title debut album went platinum in 1994.

It seems like guitarist/producer/designer Steve Ripley has always taken a unique approach to making music and the instruments he’s used. As a native Oklahoman (now residing in Tulsa), he grew up in a farming en-vironment with numerous musical influences due to what he terms “…a somewhat isolated musical location.” But he ultimately became aware of the fabled “Tulsa sound” before he ever moved there.

Ripley’s first tastes of international success weren’t due to his musical aggregation’s recordings. He recorded with Bob Dylan on the legendary singer/songwriter’s Shot of Love album, and designed an unusual stereo guitar that was subsequently marketed by the Kramer guitar company in the mid ’80s.

The affable veteran garnered acclaim in ’94 when his band, the Tractors, sold over two million copies of its self-titled debut album. The members of the Tractors each have decades of experience, and their former musical associations make for an impressive resumé; keyboard player/co-producer Walt Richmond has worked with Bonnie Raitt and Rick Danko, guitarist Ron Getman worked with Janis Ian and Leonard Cohen, bass guitarist Casey Van Beek with Linda Ronstadt and the Righteous Brothers, and Jamie Oldaker has drummed for Eric Clapton.

What’s more, Ripley has continued to design innovative guitars. One of his latest creations is the D-neck, a bolt-on that ex-tends a guitar’s sonic capabilities by two frets.

The updated version of Tom Wheeler’s American Guitars noted you moved your guitar enterprise to Tulsa. Are you originally from there?

I grew up on a farm about an hour from Tulsa – a little town called Glencoe. It was a family farm we got in the land run, like in the Tom Cruise movie (chuckles).

Do you think there’s a stereotypical Tulsa sound? If so, what is it?

I think there is a Tulsa deal of some kind. For me, it goes back to [J.J.] Cale a lot – I paid attention to what I call the J.J. Cale/Leon Russell school of recording. We tend to make records just like Cale did. A lot of the playing is done one guy at a time, and you can stick the mic back and go for his first take; you don’t worry about the drum sound or the headphone mix. Wingin’ it is part of it, and you build a record. I call Cale for therapy – Uncle J.J. (laughs).

But a big part of it also has to do with shuffle and western swing; Bob Wills’ “Stay All Night, Stay A Little Longer.” The Wills guys called it the “two-beat.” Slow that down, and pretty soon you’ve got “Crazy Mama” (a Cale-penned tune).

Some might call it “laid back” music.

Well absolutely, for Cale. If you looked up “laid back” in the dictionary, his picture would be next to it! But blues was a big part of the Wills thing, as well, and Jimmy Reed slips in there. Then Chuck Berry at some point, and the groove gets all-important.

And I think that culturally it had to do with being in the middle of America, with influences coming from all directions; a real melting pot. But Tulsa was never a place to play and make money in a band. The clo-sest big town was Stillwater, which had Oklahoma State University, and almost directly to the south was Norman and O.U. If you could learn “Walkin’ the Dog,” “What’d I Say,” and something else, you could get a fraternity gig.

You’ve said you’ve only had two gigs – driving a tractor and playing guitar. So I need to ask who you were listening to when you were farming.

My first records were 78s by Bob Wills and Hank Williams; I’d play them in my Uncle Elmer’s farmhouse. I played “Settin’ the Woods on Fire” and “Stay All Night, Stay A Little Longer” over and over. We were almost cut off, living on a farm in Oklahoma. There were two TV channels and almost any kind of entertainment that made it to there could change your life.

I fell in love with a lot of the guitar work on early Elvis records, and before that there was Eldon Shamblin (of the Bob Wills band). I’d buy anything with a guitar in it – any magazine, any record; it didn’t make any difference.

And the Ripley way of farming meant you started driving a tractor around age eight or nine. There were big tractors for the grown-ups, and little tractors for the little folks. I did most of my plowing with a little transistor radio strung over my shoulder, and a tiny 10-cent earpiece.

Back then, music was really mixed together, at least in Oklahoma. You’d hear Buck Owens alongside Ray Charles. Chuck Berry and Luther Perkins were important to me. Jerry Lee [Lewis] was exciting, but the guitar playing on his records was great, too. And the Ventures was extremely important during that period, particu-larly to anyone just starting to play.

And that’s all pre-Beatles. What’s great about the Tractors is these are the first guys I ever played with in a serious band that started listening to music before the Beatles, like me. That’s no knock to the Beatles, but most people our age started playing in bands because of the Beatles.

There were instrumental songs by bands besides the Ventures, like “Pipe-line.” When the Astronauts came to Oklahoma, it was a big thing. One reason the Beatles hit so hard here is because they’d grown up listening to the same things we had; they loved Carl Perkins and James Burton. It was a real kinship.

Tell me about some of your instruments and bands.

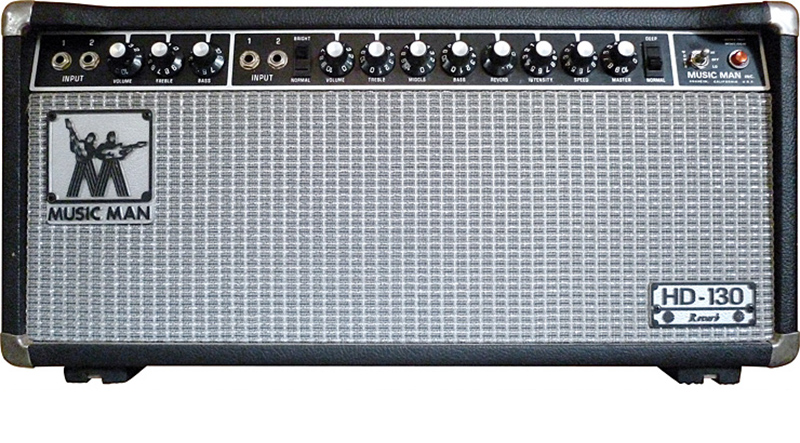

My first guitar was a Jazzmaster. I worked all summer for 50 cents an hour and bought a calf with that money, and when she had her first baby, I sold them and bought the Jazzmaster and a Princeton tremolo amp. I’ve been a tremolo freak ever since, and my biggest lament about the music business is that about 15 years ago, they stopped put-ting tremolo on amps (chuckles).

That Jazzmaster was stolen, and I bought a Gretsch Tennessean. I loved that guitar, as well, and played Gretsches for a long time. I can look back and see how their tone was world-class, but I loved them because they fed back so easily. Back then, when we were playing something like “I’m A Man,” you could stick that Gretsch right in front of a speaker, and it’d go WOWOWOWOW. I’m not afraid to say I liked that sound (laughs)! I never could play quite like Hendrix, and I was still playing “Tiger By The Tail”…with feedback!

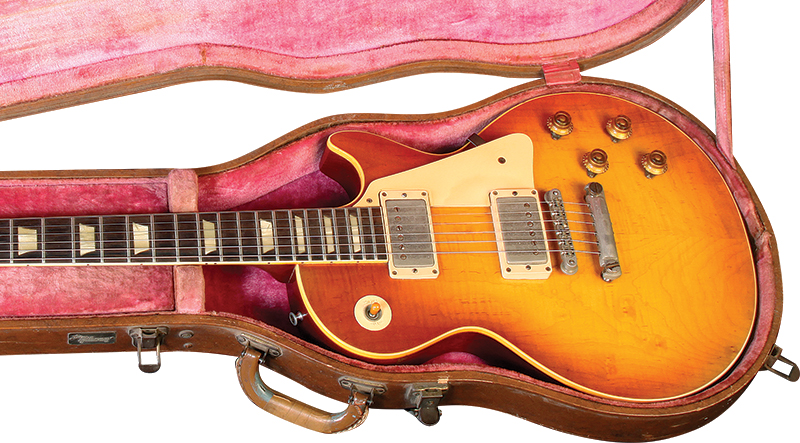

Then there was another significant change in my life: I was having trouble keeping my hollowbodies in tune, so I went on a pretty heavily researched quest when I was 18. I played a Les Paul for awhile – a triple-pickup black beauty, and I wish I still had it. I played a Stratocaster for a little bit, then I heard a phenomenal player in a town called Enid, and he played a Telecaster. I can remember think-ing how great it sounded, but I was saying, “Why didn’t he get himself a real guitar?”

At some point I tried a Telecaster, and that’s what I’ve played ever since. My friend and I bought paisley Teles because they were practically giving them away in Tulsa, at a place called the Guitar House, where Eldon hung around. But we were more lucky than we thought, because Fender had a warehouse right there in Tulsa. I played that paisley Tele up through Bob Dylan.

Is it fair to say when you worked on the Shot of Love album and tour, you might have thought you’d made the big time?

Well, my bands did the usual songs; we still did “Tiger By The Tail,” but got into Creedence and Van Morrison, then when we started doing Crosby, Stills & Nash songs we had to go further out of town to play, because we couldn’t sing like that (chuckles). Then there was the horn thing Chicago and Blood, Sweat & Tears. And to be honest with you, when Styx, Foreigner, and Journey happened, I pretty much quit. I went into the studios. I met Cale, and he really got my juices flowing about his kind of music. That happened around ’76, and the next time I was in a band was with Bob Dylan in ’81. I was in a band with some amazing players.

When did you start building your instruments, and why did you go for that option?

I was Leon Russell’s engineer for a couple of years, and in that pursuit of “how to make a record,” I was placing mics inside Leon’s Steinway. If you stick your head into a Steinway, and Leon Russell’s playing, it’s the biggest, most wonderful stereo thing you’ve ever heard. It was my goal in the control room to get that big stereo spread, just like I heard when I stuck my head under the lid. The frustration as an electric guitar player was that I couldn’t get a big, naturally-occurring stereo spread without effects. You’d have to put in a chorus, or double the guitars something to give it some movement in the mix.

So I tried to make a six-channel guitar so I could spread the amps across the room and record them in stereo, but I wanted it to sound like a regular guitar; I wasn’t into effects.

Red Rhodes had made a 10-channel pickup for his steel guitar, and he made me two six-channel, Strat-type pickups. I chopped up my paisley Tele, and made it into a six-channel guitar.

Are you saying you made your first six-channel guitar more for recording than market potential?

I did, and I talked with a drummer from Tulsa named Jim Keltner, who’d played with John Lennon, and he was a Wilbury, too. He told me he was working with Bob Dylan, and I told Jim I’d love to meet Dylan if there was ever a chance. Jim called me up one day and said, “Dylan told me to bring some players down because he wanted to go over some songs.” I only had my chopped-up paisley six–channel guitar, and I thought it might be a bit presumptuous to play through six amps in front of Bob Dylan, so one day on the way to re-hearsal, I bought a Tapco mixer and I plugged each string into its own channel, so I’d have a pan pot for each one, and I played out of two of Bob’s amps. It was great, because if you wanted your low E to be on the right, you could pan the string accordingly. I thought it was a real breakthrough, and I toured with Bob for two years. When we broke for the holidays at the end of ’81, I made a couple of gui-tars with pan pots built into them, so I could just plug in a stereo cord and play.

Then Cale bought one, and Steve Lukather bought one, and Fred Tackett bought one – he was a big L.A. session player back then. Now he’s a member of Little Feat. Alan Holdsworth bought one, so it got easy to sell them. Eddie Van Halen became a big supporter.

When you recorded with your original “Frankenstein” Tele – before you began using the mixer and pan pots– would you plug into six channels in a board or six amplifiers, or some combination?

I would do it every way I could. Most of the time, I played through six amps, and sometimes I’d record them each on a separate channel. Sometimes I’d put up some stereo mics; that was my favorite, but I also went direct, and I even did some experiments where I ran the three bottom strings through octave dividers and ran through three more amps – a total of nine amps at once. It was bizarre, but it was still in an experimental stage. I’d bring over guitar players and sit ’em in the middle of the room and let ’em play this experimental guitar. They were all astounded, which led me to think I could market such an instrument.

Is it fair to say the general perspective among guitar aficionados is your instruments are known from the Kramer association?

I think so. More people would probably have known about it through the connection with Van Halen, which became the Kramer connec-tion, although all of Eddie’s guitars were custom Ripleys, not Kramers. I think Kramer actually did a pretty good job of taking it to the mar-ketplace.

One of your more recent innovations, the D-neck, apparently goes for a differ-ent tone.

And that’s my favorite idea out of everything. There was literally a time when I said, “Eureka!” when I was working on it. A lot of us love to tune down; I play in D a lot. The strings feel floppy, and that can be a good thing.

I’m not a luthier; I’m a designer. Tom Anderson made most of my stuff. He has his own company now, but he was a Schecter player when I was with Bob. I designed and soldered and put ’em together, but I can’t take credit for sawing out a piece of wood, because it never did appeal to me any-way. And he’s the guy making that neck for me.

The great thing about Fenders, and what makes them so different from Gibsons or other traditional instruments, is that all of the other stuff was sort of “luthier things” – carving, sawing, sanding, and shaping. The design of Fenders was important, but the tool-making was paramount, so they were consistent. If you did it right, you’d have a batch of necks that could be put on any body from another batch. If they’d sounded bad, they never would have gone anywhere, but they sounded great.

When you figure out where to put the frets on a guitar and you figure out the scale, there’s a twelfth root of two formula, which is 1.059463, and it hit me one day that I could use that formula to find where an E-flat and a D would be if you wanted to make a longer neck. What I yelled, “Eureka!” about was figuring out that you could bolt it onto any Fen-der guitar with a 251/2″ scale; you wouldn’t have to make a whole new guitar.

Now I have sort of a family; the one I play all the time is in D, and is two frets longer, but I’ve also got one that’s three frets longer and tuned to D-flat, and one that’s even longer and tuned to C. You can use the same strings you’ve always used on these necks; you don’t have to think of it as a weird instrument.

Next month, Steve Ripley (who says he’s now out of the guitar business) discusses his musical ventures with the Tractors.

This article originally appeared in VG June 1999 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.