1959 Vega Director Model A-60

• Preamp tubes: 7025, 12AX7

• Output tubes: two 6V6GT

• Rectifier: 5Y3GT

• Controls: Volume, Volume, Tone (doubles as power switch)

• Speaker: 12″ Jensen P12R and 8″ Quam

• Output: approximately 15 watts

A worthy vintage combo in all regards, there’s sad irony in the fact the Director Model A-60 is representative of the downward trajectory of Vega, the company founded in 1881 by Swedish-born brothers Julius and Carl Nelson.

Established as a mandolin and guitar maker, Vega became one of the biggest names in banjos in the early 20th century and for a time was poised to be a major player in the first guitar boom just before and after World War II. In 1959, there was no reason an aspiring electric guitarist wouldn’t purchase a Vega amp and believe he or she was tapping into one of the great names in American instrument manufacture.

Given its configuration of two Volume controls, one Tone, a pair of nine-pin preamp tubes, a pair of 6V6GTs, and a 5Y3 rectifier, it’s easy to assume the Director A-60, like so many mid-sized amps of the era, was just another Fender 5E3 Deluxe knock-off. Such an assumption would be way off base. Careful tracing of the circuit by this amp’s owner, VG reader Brian Centofanti, reveals the signal follows a rather convoluted path and that – while still not particularly complex – is quirkier than the straightforward 5E3.

The inputs share the first Volume control, which goes through first a 33k resistor then a .005µF capacitor before entering the first gain stage, half of a 7025 (a rugged 12AX7 equivalent). This tube appears to be grid-leak biased, a technique most guitar-amp makers had abandoned in the early ’50s in favor of cathode biasing. High-voltage DC reaches the tube via a 250k resistor connected to the plate. The signal exits the 7025’s plate on the way to the Volume control via an odd dual-.004µF cap, with two leads tied together in parallel to render it .008µF total. The third input, labeled “Inst 3 or Micro,” is odder still; it runs through .001µF and .005µF caps in series on the way to its own half of that first 7025 dual-triode.

The second preamp tube, a 12AX7, appears to be used in standard configuration with the first triode acting as a second gain (a.k.a. “driver”) stage prior to the split-load phase inverter provided by the second triode, which splits the signal into opposite phases and feeds them from the plate and cathode to the 6V6s. Like most of its type, the output stage is cathode-biased and the Tone control is a simple treble-bleed network tied to the Volume controls. With 363 volts DC on the plates of the 6V6s, 289 volts on the screens, and given the size of the modest output transformer, the amp is likely putting out about 15 watts. All of this is rendered in the strangely appealing agricultural-grade “rat’s nest” point-to-point wiring often used by second- and third-tier amp makers of the day, with a preponderance of ceramic-disc signal caps, which can often lend a little extra grit and texture to the tone.

By all accounts, Vega wasn’t manufacturing its own amps at this time, but the origins of this one are not easy to discern. For assistance, we turned to Terry Dobbs – a.k.a. “Mr. Valco” – who’s an authority on sundry “catalog-grade” amps. According to Dobbs, the Director A-60 has a lot in common with the Harmony H204 and the R500 from Lectrolab of Cicero, Illinois (just outside Chicago), which jobbed many amps for other brands; the schematics he showed us do bear many similarities in the preamp stages, in particular, though it isn’t identical to either. So… who knows?

Unmentioned among the specs so far is that enticing extra speaker in the cab alongside the toothsome, teal-framed 12″ Jensen Alnico P12R. An 8″ unit made by Quam, it’s wired in parallel with the Jensen, with a crossover capacitor (a 2µF electrolytic cap) in series with the positive connection to dump low frequencies and prevent “flubbing out,” essentially rendering it a tweeter.

On top of all that’s going on under the hood, how extremely cool does this thing look? The brown-and-orange cabinet is stylishly partnered to a tweed grillecloth with a far more luxuriant look than Fender twill and the Vega name declared by a reverse-etched plexiglas plate; it’s surprising no retro-minded boutique builder has borrowed the aesthetic. The chassis and control panel follow through with similar elegance courtesy of a hammered-gold finish with maroon key lines around the inputs and controls, reminiscent of trends from two decades earlier than its manufacture. Particularly appealing is the legend “Fidelity Amplifier” on the control panel beneath the model name; given the circuit beneath the hood, it was a bold claim even in 1959, but makes for a nifty marketing slogan (you may recall the ’39 Vega Model 120 we featured last year similarly billed itself as a “High Fidelity Amplifier”).

The Director A-60’s build quality, however, is less-robust than its styling. Beneath the sartorial splendor is a pressboard cabinet (with wood reinforcement in some places), and an open L-shaped chassis made from thin steel. Nonetheless, it has held together well enough these 58 years. Partial thanks for that are likely to go to the amp’s original owner, from whom Centofanti purchased it 10 years ago. Since then, he has only done necessary maintenance to keep the amp functional – replacing some electrolytic capacitors and adding a grounded three-prong plug.

“The amp sounds great with a Tele – clean, punchy, and bright with Tone at max, and it starts to get gritty at about three on the Volume control,” Centofanti said.

All in all, the Vega Director A-60 is an alternative means of acquiring appealing vintage tone, and one that won’t likely break the bank – if you can find one.

This article originally appeared in VG July 2017 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Blues guitarist/singer Lonnie Brooks died April 1 in Chicago. He was 83.

Blues guitarist/singer Lonnie Brooks died April 1 in Chicago. He was 83.

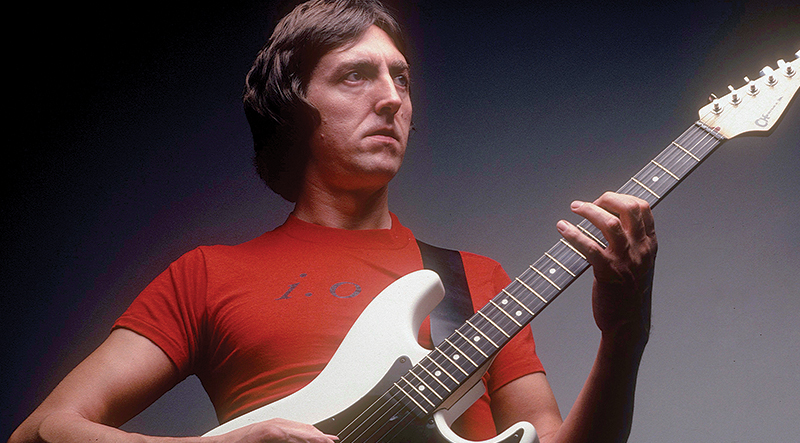

Allen Hinds has spent a considerable amount of his 60 years playing guitar, and has kept busy lately with two new releases while also teaching at Musicians Institute, doing session work, and touring Japan and/or Europe a time or two each year. All this came after years of gigging with various acts and a late-blooming solo career that started circa 2005.

Allen Hinds has spent a considerable amount of his 60 years playing guitar, and has kept busy lately with two new releases while also teaching at Musicians Institute, doing session work, and touring Japan and/or Europe a time or two each year. All this came after years of gigging with various acts and a late-blooming solo career that started circa 2005.

It’s also interesting that if a specific model was discontinued, Gibson did not discard the completed fingerboards (or other parts) intended for it. A good example is the L-Century flat-top produced from 1933 until ’39, which had a white-celluloid fingerboard with inlaid rosewood inserts which in turn had inlaid mother-of-pearl patterns. The rosewood inserts were produced by cutting up leftover tenor-banjo fingerboards, which in turn produced a variety of inlay pattern deviations from the L-Century’s catalog spec.

It’s also interesting that if a specific model was discontinued, Gibson did not discard the completed fingerboards (or other parts) intended for it. A good example is the L-Century flat-top produced from 1933 until ’39, which had a white-celluloid fingerboard with inlaid rosewood inserts which in turn had inlaid mother-of-pearl patterns. The rosewood inserts were produced by cutting up leftover tenor-banjo fingerboards, which in turn produced a variety of inlay pattern deviations from the L-Century’s catalog spec.