Fretted instruments can be examined in much the same way as zoological taxonomist or forensic pathologist would approach them. They fit well into a Linnaean taxonomic order, and in fact that is very much the approach we use in identifying and dating fretted instruments.

In addition, these instruments can be examined much the same way a forensic pathologist would examine a body to determine what has happened to it during its lifetime, including any modifications, damage, or previous repairs. The conclusions we reach are constantly changing, adapting and hopefully always getting closer to the truth.

For the serious scholar, it is important to work from as many primary sources as possible. Primary sources are defined as evidence which has not been interpreted or compiled. Examples of primary sources in the vintage instrument world would include unadulterated exemplars of the instruments themselves, and internal factory documentation which is contemporary with the production of the instruments in question. When I started into business almost fifty years ago, examination of the instruments themselves was my foremost source of information. Especially valuable were examples which included provenance like an original bill-of-sale. By comparing and describing the physical characteristics of such examples alongside other documented instruments I was able to begin to form the outline of what is known today. I was also in a position to see a significant number of these examples, a necessary condition in order to draw valid conclusions.

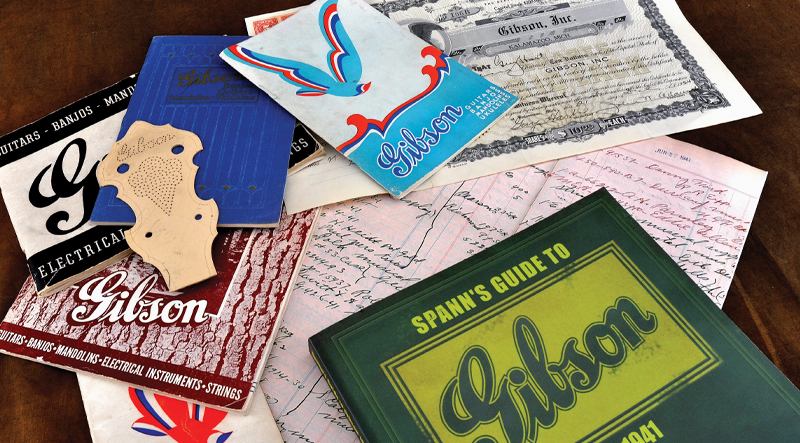

Of lesser value are company catalogs, trade magazine material (articles and advertising), and perhaps surprisingly, employee interviews. Any lawyer can easily explain why eyewitness accounts are not considered as reliable as other evidence, especially when many years separate the event from the witness. Company catalogs and advertising literature, can provide general guidance, but it should be noted that many models were introduced prior to their introduction in any literature and catalog descriptions are not always completely accurate. For example, in the pre-1930’s catalogs Gibson referred to many mandolins and guitars as being made with maple back and sides when in fact many of these models featured birch rather than maple. Catalog art was often notoriously inaccurate, frequently depicting outdated specifications and appearance.

Company shipping ledgers and other internal factory correspondence were not available to us fifty years ago. These documents often provide much greater in-depth and more reliable information than catalogs or advertising literature. Some researchers such as Joe Spann who was spent over 40 years studying Gibson literature and Greig Hutton who has spent many years studying Martin ledgers going back to the 1830s have amassed a treasure trove of information which in quite a few cases has caused us to have to revise some long-held opinions when confronted with incontrovertible new factual information.

The researcher’s quality of education also plays a crucial role. The wide knowledge of an educated mind brings many important factors into play which allow for better interpretation of evidence. For example, it is impossible to fully understand and correctly interpret the actions of Gibson and Martin in the early 1930’s without underlying historical knowledge of the Great Depression. The designs of C.F. Martin Sr. cannot be correctly understood without knowing the influence of the classical Spanish school and the German luthiers of Markneukirchen. The popularity of the guitar in America is a study which includes early classical pioneers like Madame de Goni, as well as the rock-n-roll of Chuck Berry.

Perhaps not so evident on the surface are the innate abilities of the individual researcher. Qualities like imagination, intuition, pattern recognition and powers of synthesis are all of supreme importance in evidence interpretation. A danger to be avoided at all costs is the tendency to describe the motivations of people in the past through the lens of present-day knowledge. It is easy to immortalize people as “genius” or events as “landmark” when in fact they were not considered as such at the time. The Gibson F-5 Master Model mandolin and the Les Paul Model guitar were both commercial failures when originally produced. It was in large measure subsequent events in the evolution of music which brought these instruments to worldwide acclaim. The 1943 obituary of former Gibson acoustic engineer Lloyd A. Loar does not laud him as a genius designer, but merely as a proficient musician. History is replete with examples such as these and the researcher must be conscious of the tendency to create revisionist history.

Unfortunately, published Information often becomes concretized in the public mind, accepted as truth, when in fact it is sometimes merely ill-informed opinion. Much information which was originally published in book form has now been transcribed to the Internet, allowing its instant and worldwide dissemination. Earlier ideas, over time and with uncounted repetition, have become widely accepted or even more dangerous, entered the realm of dogma. I have been in business long enough now, that it is not uncommon for me to talk with well-meaning individuals who wish to debate historical points, based on out-of-date information that I myself would have accepted in the past.

When all of these research techniques are combined, we have a more accurate view than any one technique alone. Detailed inspection of significant examples, access to internal factory documents, and an educated mind which can liberally use knowledge, imagination, and intuition create the ever-changing landscape of vintage fretted instrument research. Any research which does not evolve over time and uses absolutisms like “always” and “never” should be viewed with healthy skepticism.

This article originally appeared in VG December 2017 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

After a lengthy illness, jazz guitarist John Abercrombie died August 22 at a hospital outside Peekskill, New York. He was 72.

After a lengthy illness, jazz guitarist John Abercrombie died August 22 at a hospital outside Peekskill, New York. He was 72.

Tom Feldmann burst out of Minneapolis with an authentic take on acoustic blues unlike anything heard in years. Gifted with fine slide and fingerstyle chops, he also possesses a strong, gritty voice. His new album, Dyed in the Wool, showcases his heartfelt and powerful compositions.

Tom Feldmann burst out of Minneapolis with an authentic take on acoustic blues unlike anything heard in years. Gifted with fine slide and fingerstyle chops, he also possesses a strong, gritty voice. His new album, Dyed in the Wool, showcases his heartfelt and powerful compositions.