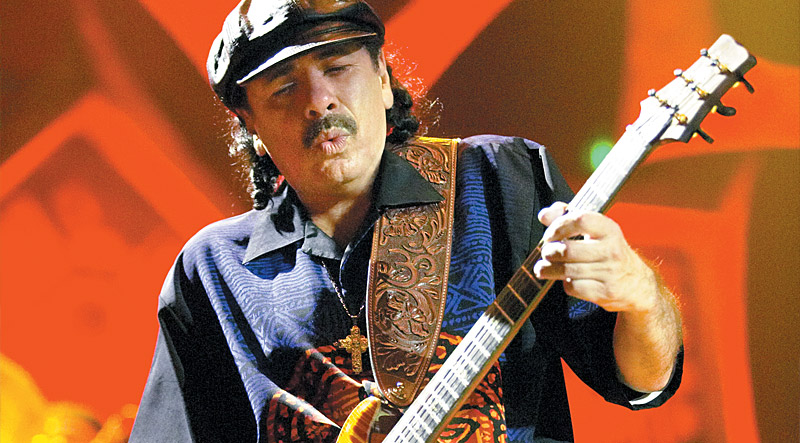

Carlos Santana is illustrating a point. “Most people play like this – around the note,” he says, making a fist with his left hand and rolling his right hand around it. “I play like this,” he explains, inserting his right index finger into the middle of the fist. “Into the note.”

Seems simple enough. But no matter how much you practice, how zen you try to be (becoming the note), even if you were able to play through the exact same guitars and amps that Carlos discusses in this issue’s accompanying sidebar, you will never sound like Carlos Santana – and he’s provided a perfect illustration why not. This is Carlos Santana’s left fist, Carlos Santana’s right index finger – the hands of Carlos Santana. And he owns the only pair.

The biggest compliment any musician can receive is a thumbs-up to the old Les Paul yardstick: “Can his mom pick him out on the radio?” (Or to bring Les up to the P.C. present, “her mom.”) In other words, have you got your own identity?

Santana, it would seem, passed that test long before anyone ever heard of him. Practically from the moment the band that bears its leader/guitarist’s name stepped onto a San Francisco stage in 1966, it (and he) were breaking new ground. Soon dropping “Blues Band” from its name, Santana’s combination of wailing, crying guitar and Afro-Cuban rhythms cemented a unique place in rock history. And as the late Bill Graham, rock impresario, said in a rare interview in 1977, “I think there are only two guitarists who I could pick out if you played a thousand different guitarists – Carlos Santana and Albert King.” Or, as J.J. Cale (a distinctive guitarist in his own right) put it a decade after King’s death, “Carlos Santana is the most identifiable guitarist in the world.”

Born July 20, 1947, in Autlan de Navarro, Mexico, Carlos was playing guitar in Tijuana strip clubs before reaching puberty. After moving to San Francisco with his family at 15, he soon left the Bay Area to return to playing T.J. nightclubs, eventually moving north and reuniting with his family in ’63.

After becoming a favorite attraction at Graham’s Fillmore Auditorium, Santana was signed to Columbia by Clive Davis and played Woodstock before its self-titled debut album was released. The Oscar-winning documentary of the festival shows the young band (with Carlos then 22) playing “Soul Sacrifice” in typical, high-energy form.

That “flame-on” attitude, as Carlos calls it, has stayed lit in the 35 years that have followed, although commercial success waned as the guitarist pursued more introspective solo projects and collaborations with jazz icons such as John McLaughlin, Alice Coltrane, and the former members of Miles Davis’ quintet (Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams).

But 1999’s Supernatural reunited him with Clive Davis, who suggested an eclectic album of collaborations with younger acts. The CD yielded the hit singles “Maria, Maria” and “Smooth” (co-written and sung by Matchbox Twenty’s Rob Thomas), claimed nine Grammy awards (including Album Of The Year and Record Of The Year), and went 25 times platinum – at one point selling 500,000 units a week, which was the total worldwide sales of Santana’s previous effort.

Like Supernatural, 2002’s Shaman shot to the top of Billboard’s album chart, and yielded two hit singles – “The Game Of Love,” featuring Michelle Branch, and “Why Don’t You And I,” sung by Chad Kroeger. And Carlos’ impassioned guitar ranks with his best work on cuts like “America” with P.O.D. and “Novus” with opera legend Placido Domingo.

Carlos and his wife, Deborah, who established the Milagro Foundation in 1998 to support underserved children in the areas of health, education, and the arts, donated all of the proceeds from Santana’s 2003 American tour to Artists for New South Africa (ANSA) to fight the AIDS pandemic.

In an exclusive interview, Carlos suggests that 2005’s All That I Am (with appearances by Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler, Metallica’s Kirk Hammett, steel guitarist Robert Randolph, Mary J. Blige, and “American Idol” runner-up Bo Bice) forms the last installment of a star-studded trilogy, at least for now. He also discusses his eclectic palette of influences, heroes from boogie king John Lee Hooker to Brazilian guitar great Bola Sete, how he views collaborations, and future projects. And he offers tips to aspiring guitarists, as only Carlos could express them. “If you’re taking a guitar solo, let the juices flow, the light come out through you,” he stresses. “Like I’ve said before, people are flowers, I’m a hose, the music is the water and the light. Let it flow. Don’t block it with your ego or your insecurities or your mind. Tell your mind to get the hell out of the way, and play right from the heart.”

Vintage Guitar: When did your family move from Mexico to San Francisco?

Carlos Santana: My family came here in ’62, right at the same time that the Yankees were playing the Giants in the World Series. And then I went back to Tijuana for a long time again, and then they got me back in ’63. I came to America right before they shot Kennedy.

But when you went back, you were only 15 and on your own?

I was on my own, just working nightclubs. Which was great. It was a great education. Tijuana is just like Richmond or Oakland or Broadway or New York. Once you take the dimension that there’s danger everywhere, then you know how to carry yourself. That’s the key word. You’ve got to know how to carry yourself – in front of Miles Davis or Stevie Ray or a guy with a switchblade in Tijuana. How you carry yourself, the people are going to respect you. Being a kid, people would be very careful not to smoke pot around me – which I knew they were doing because it smelled all over the place. But in Tijuana I did learn so much about how music can be supremely sensual to women. If I learned anything in Tijuana, it’s how to grab the women’s attention – just like a snake can charm a rabbit. I went to see Paco de Lucia and Al DiMeola and John McLaughlin at the Masonic Auditorium in San Francisco, and during intermission I went to talk to them. Paco was still practicing, and I said, “Paco, you make a lot of women happy out there when you play.” He looked up and said, “Very important.” Who wants to play with just a bunch of guys? That’s what I learned in Tijuana: how to resonate with the female.

I just recently became aware of the guitarist Javier Batiz. Did you listen to him growing up in Tijuana?

This was in 1958, ’59, ’60. If you hear B.B. King from ’64 to ’67 – which is like Peter Green and Michael Bloomfield – and then the most beautiful sound from Freddie King. Not when he sounded thin and frantic. Before the coke, when they were drinking guys and the tone was a little fatter. That was this guy’s tone. Being a kid in Tijuana, when I first heard this sound, it was like seeing a whale step out of the ocean, or a flying saucer; I just knew in that moment that I wouldn’t do anything else in my life other than just play the guitar – no matter what the guarantees or the consequences. This guy, Javier Batiz, was a combination of B.B. King, Ray Charles, and Little Richard. I mean, he had those three guys down.

So I followed him like a dog, but he wouldn’t teach me anything. Every time he’d catch me looking at him, he’d always turn his back to me. Now he claims that I learned everything from him, but he was a really stingy mother. See, the people from the old days, they didn’t have tape recorders or cameras. So they guarded what they had. The motto for those people was, “Never give a cripple a crutch to cross the street, because they’ll kill you with it.” So he was really paranoid that I was going to steal some stuff from him. Which I knew, “Well, you got this from Little Richard, Ray Charles, and B.B. King – I’ll just hang out with B.B. King.” So I came to San Francisco and hung out with Michael Bloomfield and B.B. I went to the master’s masters to learn.

I’m really grateful to God for allowing me to live in this particular time. In 1966, I went to Sigmund Stern Grove to see John Handy, Bola Sete, and Vince Guaraldi. It was incredible. And I saw Bola open up for Paul Butterfield and Charles Lloyd at a matinee at the Fillmore. Imagine that. I was there! From ’63, when I came to this country, I was really blessed that people like B.B. and Miles, John Lee Hooker, Charlie Musselwhite, Bill Graham, and Clive Davis just adopted me. The honeymoon has never been over between them and me. I’ve never had a musician be nasty towards me. People know that I’m honoring them in my music.

What was so special about Bola Sete?

Bola Sete is a gentleman who could play like Segovia in a second, Charlie Christian the next, T-Bone Walker, Wes Montgomery, and Chuck Berry in one breath. And he’s not even looking at the guitar! If you saw Jimi Hendrix and Bola Sete in the same night, he’d probably be louder than Jimi Hendrix. I don’t mean in volume; I mean in brilliance. I think even Jimi Hendrix would go, like, “Uh-oh.” Like when you see Ravi Shankar or Ali Akbar Khan or Bola Sete, you’re dealing with a different kind of genius.

When you’re playing acoustic as opposed to electric, are you thinking of different influences and resources, or is it all just guitar?

No. A long time ago, I gave up listening to Manitas de Plata and Juan Serrano and all those guys – same as with Buddy Guy and Otis Rush. I realized that no matter what I do I’m going to sound like me, anyway. I’m not going to sound like Paco de Lucia or Al DiMeola. At this point, since I surrendered – knowing that, good or bad, I’m going to sound like me, whatever that is – I just think of three things. It’s like combining joy, anger, and orgasm into one. If I can make those three things into that note, then I don’t have to think about sounding like somebody else. It’s the same thing I tell my musicians: I don’t want to see anybody talking on the phone and making love at the same time. Hang up the freaking phone or put the woman on the side. Whatever you’re going to do, do it 1,000 percent into it. When I play guitar, I don’t think of the way Otis Rush would do it or Buddy Guy or Paco de Lucia, because I can’t play like them, even if I tried. The last few years, I just think of something very intense. I don’t mean to be raw or crude or vulgar, but an orgasm sounds fine. Right before you let it go… that one.

The thing, to me, that I’m really grateful for, is that for some reason, besides playing guitar and being a musician and all that kind of stuff, God gave me the gift of attracting things that are really once in a lifetime. Like being with Jaco [Pastorius] the night that he died. We were the last people he played with and hung out with. John Lee called me the night he (John Lee) died. That night I was in the studio late, and they said, “Man, John Lee passed.” So I came home, and there was a message blinking. I turned it on, and it was him. [Imitates Hooker’s deep voice and stutter] “Wh-wh-what’re doing young man? C-c-call me sometime; I wanna hear your voice.” I was like, “Damn!” I save all those things. That’s why I called the CD All That I Am – because I’m a part of all those people that I love, all the things that I love. I am a part of Miles Davis, Jaco, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, McCoy Tyner, Buddy Guy, Otis Rush. I’m fortunate that I don’t have to sound like them, because they’re already the best at what they do.

When I was in the studio with John Lee, you know he always wore his sunglasses. We were playing, and he said, “You know why I wear these?” He lifted up his sunglasses, and he had tears in his eyes. He said, “Because my blues is deep.”

On “The Healer,” it sounds like you and Hooker are both improvising.

Well, I went to his house on his birthday, and I told him I had a sketch of this thing called “The Healer.” I said, “It sounds like the Doors’ ‘When The Music’s Over,’ which sounds like you – I know they got the riff from you, man. So we’re going to rescue it back.” As soon as I played it for him at his house, he made up the lyrics on the spot. I said, “Don’t say any more; just save it for the studio.”

I told him not to come to the studio until 1 or 2 o’clock in the afternoon. I wanted to make sure the sound was right, rehearse the band, set the mood, get the right tempos. I said, “So when you walk in, like the master chef, the stove is hot, the spice is there, you just start cooking.” “Okay, I’ll do what you say.” He came in, and that’s how it happened – one take. The only thing he overdubbed was, “Mmm, mmm, mmm.” I said, “Would you mind going back in?” “For what?” “Just do a little bit of mmm, mmm, mmm at the very end.” “Okay, I’ll try it.”

It was the same thing recording with my brother, Buddy Guy. I have a deep respect and admiration for Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, B.B., Hubert Sumlin – all of them. Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Peter Green, Michael Bloomfield – we all know who to go to and what to listen to so we can soak ourselves. We don’t want to sound like them, but we want to be drenched with the same things that they’re drenched with. It’s a pure emotional thing that transcends being black or Jewish or white. I mean, Pavarotti sings the blues, man. So does Placido Domingo. So do Japanese people and people in Persia. It’s all about the deep feeling inside. Like Miles Davis said, “My mama’s good looking, my daddy’s rich, I never picked cotton, I never suffered or intend to suffer. But I can play some blues.”

Buddy Guy and I talked about how they made up this thing about Robert Johnson getting on his knees at the crossroads. That’s just a bunch of baloney. The only way you get to play like that is, first of all, God’s gift, and the second is you’ve got to practice your ass off, day and night, like Jimi Hendrix or Stevie Ray – until playing the guitar is like breathing; you don’t think about it. All that talk about selling your soul to the devil – I got news for you: it’s Hollywood bull****; it doesn’t work. Plus, if you’re that hard up to do something like that, that’s cheating anyway. The devil cannot make you play divine. Coltrane is divine; Stevie Ray is divine; Jimi Hendrix is divine; Robert Johnson is divine. The devil can only shadow. I don’t see shadows around Robert Johnson; I see light.

Did you go through a period when you were groping around and eventually found your sound and personality, or was that there from the start?

I think it was from the start. I always listened to all the Kings – Freddie King, Albert King, B.B. King – and Lightnin’ Hopkins, Jimmy Reed, John Lee Hooker, but I never could sound like them, so I stopped trying. It always sounded like me. After a while, I said, “Ain’t no point in fighting it; I just sound like me.” Same with Gabor Szabo, Bola Sete, Wes Montgomery, Larry Coryell – everybody. I’m very grateful to God that I have my own fingerprints. Everyone has their own fingerprints, but nowadays they have tape recorders to slow things down and keep the same key, so you can cop Django Reinhardt or Charlie Christian stuff. Why don’t you do it the way Django Reinhardt and Charlie Christian did? Lock yourself in the house and don’t freaking come out until you get your own stuff!

Like what Clapton did between the Yardbirds and the Blues Breakers album with John Mayall.

When you hear Clapton at that time, and Peter Green, they both sound like B.B. King, the way he was playing between ’64 and ’67 – like Live At The Regal. That was B.B. supreme. Even B.B. had to go back to it to get to the next level. Otis Rush, Buddy Guy – they all had to go through B.B. at that point. Albert was different, but even Freddie King; he had more raw energy, but it was still B.B. King, to a certain extent. Michael Bloomfield… B.B. King. Peter Green… all B.B. King. I found myself thinking, “Well, there’s too many guys in this corral.” Fortunately for me, discovering LSD, mescaline, and peyote, I finally could discover Gabor Szabo and Chico Hamilton. Once I discovered Gabor Szabo, Charles Lloyd, Larry Coryell, John McLaughlin, Wes Montgomery, the cat was out of the bag. I wasn’t going to be a B.B. King wannabe. Plus, I wasn’t interested in becoming another “white blues guitarist.” I felt, as grand as that title is, it’s one-dimensional. I like multi-dimensional.

When I discovered Gabor Szabo, I realized something that Jimi wasn’t doing. After a while, Jimi got congas; Miles got congas; Sly got congas; Chicago got congas; the Rolling Stones got congas and timbales. All that came from Gabor Szabo and Olatunji. Santana went a different way. Because in the beginning it was the Santana Blues Band. Once we got the congas, Marcus Malone and Michael Carabello, and they started turning me on to this Gabor Szabo stuff, I couldn’t listen to the blues like I used to. All of a sudden it was more fascinating to use that in this other context, with rhythm. I could tell by the way women, particularly, were attracted. When we played in front of Paul Butterfield or Creedence Clearwater or Steppenwolf or the Who, the audience – especially the women – were like, “Damn!” So instead of the relationship between the melody, which is the woman, and the rhythm, which is masculine, suddenly women were really attracted to the rhythm. By the time I got to the melody on “Jingo,” that was it!

Next thing I know, Peter Green is hanging around – literally taking flights from his Fleetwood Mac gigs to see our band and travel with us. There was a period of about a month where everywhere we went, Peter Green was hanging out with us. To me, that was a great validation, because I adore Peter Green. I adore Michael Bloomfield. I adore people who aren’t mental people; they’re heart people. Every note comes directly from their heart. It gave me… not arrogance, but confidence that we were doing something. Peter Green, I believe, was looking for something different from B.B. King and Elmore James. Because that basically was what they did. Then they saw Santana and the Grateful Dead, and they started doing this Grateful Dead thing, writing more like Jerry Garcia, but also like Santana. But in order to play like that, they had to listen to the records the way I did and really break them down. You can’t just add congas. You’ve got to understand where to put them, and what part to play, what not to play. Otherwise, they sound and feel like stickers on a refrigerator. I never wanted the music to sound like you just stick something on. It has to be part and parcel of your molecular structure. Learn how to integrate, activate, and ignite within your own physical body. Don’t just add stickers and think that you can do it; it won’t work.

Does that attitude carry over to the albums since Supernatural,, with all the collaborations – so that they’re not just tacked on?

I guess the word is “organic.” In the ’80s, B.B. King had a hit that Bono wrote for him, “When Love Comes To Town.” It’s the same thing. Bono honored B.B. King by writing a song for him. He brought his heart to B.B. King. But it all started with Clive Davis. Because Lenny Kravitz, Mick Jagger, and Elton John tried the same so-called shtick, or formula. But that’s not what it is for us. It didn’t work for them because Clive wasn’t there to supervise. Clive is like Bill Graham. They both paid supreme, meticulous attention to the fullness of the moment. They don’t just do it just to do it. The Santana thing with guests is nothing new. I was playing with Wayne Shorter, Alice Coltrane, John McLaughlin, Herbie Hancock. This is nothing new to me. What became new was the conscious decision to get back in the race.

From ’73 to ’97, when I got back with Clive, I didn’t care about radio. Music was mainly like a background. I wasn’t conscious of the importance of a song. Whether it’s Beethoven, Nat King Cole, Miles Davis – you name ’em – they need a song. You can’t just jam. You can have a jam like the Grateful Dead, but even they need songs. Once they get to a little space, they drop “Good Lovin’” by the Rascals on you, and then everything comes together. So songs are supremely important. That’s what Clive taught me to pay attention to. I went to him and said, “You’re the person songs gravitate to, and you’re there. I see them. This song is for Whitney; this song is for Aretha Franklin; this is for Kenny G.” I said, “Do you have a song for me?” He said, “Are you open to me bringing seven songs and you bringing seven songs?” Only a fool would say no. So that’s where we started. He picked out songs and producers. Once he finds a song, they’re like glass slippers; then you find Cinderella or Cinderfella. Joss Stone or Sean Paul or Mary J. Blige. But first you go for the songs.

One thing I discovered along the way is that God’s grace is very immediate upon all of us. Can you, as an individual, get in it? And once you get inside God’s grace and acknowledge that it is there, then you’ll will things to happen. I aspire to work with Ali Akbar Khan and with Ry Cooder, and on this album I worked with Robert Randolph and Kirk Hammett. It would be nice to do something with Derek Trucks and Ben Harper. For me, it’s all about being a child in a sandbox. Bring your own bucket and your shovel [laughs]. Like Wayne Shorter says, “We may not speak the same language, but that’s not going to stop us from playing.” There’s nothing strange or weird anymore.

I never thought I would play with Steven Tyler. In the future, I’ll play with Kenny G. or Michael Bolton or Lionel Ritchie or Elton John or Billy Joel. I never thought I’d do that. Because I was the guy who was still West Side Story. I’m a Shark and you’re a Jet, and we don’t get along. But I’m not that guy anymore; that guy died. It’s beautiful to celebrate, compensate, validate, and honor people – no matter who they are. That’s what I’ve been trying to say in interviews. There was never anything wrong with Kenny G. or Elton John or Billy Joel or any of those guys; it was me. I’m the one that changed. I’m the one that doesn’t have those fears anymore. I’m complete now. I don’t care what people think. If my heart is directing to it, and my intentions are pure, I’ll play with Madonna or… what’s the other lady?

Umm, Mariah Carey?

No, Mariah Carey’s great. No, the dancer one.

Britney Spears?

Yeah! Because it’s an honor at this point. I’ve gotten into a place where it’s all the same now. Nothing’s strange anymore. We’re one body. If the song is correct, and she can sing it from the heart, let’s make people happy. Now I can get to the real purity of complementing. It shouldn’t be Wayne Shorter up here and Kenny G. down there. Hey, we’re all right here! For a long, long time, I was still very territorial, until Supernatural came along. Then I saw the eyes of Dave Matthews and Rob Thomas, how they looked at me; it’s the same eyes that I have for Harry Belafonte and Wayne Shorter. It’s just respect. So that dispelled all the uncomfortableness or feelings that I had of Kenny G. or Lionel Ritchie or Elton John. Because they’re beautiful, man. People follow their own thing. Now, can you find the right song? See, I don’t look at it anymore like John Coltrane is in the sky and Kenny G. is down there in the basement. Ain’t no up and down, left and right; we’re all right here now. Can I complement what you bring me? That’s why Supernatural, Shaman, and All That I Am work. Even the most cynical, crusty critics have to give it up and say, “Damn. This is happening.” Placido Domingo and P.O.D.; just listen to Shaman.

Your guitar playing with them on “America” sounds as passionate as anything you’ve ever done. Was there ever a period when that waned, or is that synonymous with music for you?

No, I never woke up flat, like a 7-Up without bubbles. By the grace of God, I’ve never woken up where I don’t feel it. God gave me “flame on.” I get angry really quick; I get horny really quick; I get holy really quick. Do that before you go onstage. Flame on. Whatever it is you play – Joe Pass or B.B. King – flame on. Don’t be shucking and jiving; don’t be half-hearted. Flame on or shut up and don’t play. I like Metallica for that – that energy. I love Albert King ’til the day he died, same way. If you die going for it, then die. God will take care of my family – God will take care of everything – so I’m not afraid to go for that note and have a stroke and not be able to play ever again. When I hit that note, I know it’s going to be a mother! So flame on.

Watching Jimi Hendrix, Albert King, Otis Rush – all of them – I never saw them just fax in the music. Soul, heart, mind, body, cajones – every note. Same thing with Eric or B.B. or Jeff Beck. So I would never dishonor them by just playing half-hearted. There’s no room for that. Do something else at that point. Find whatever it is that your full passion is all in it or don’t do it. Otherwise, it’s a disservice, and it’s noise. It’s just pollution. Music, to me, is a healing force. You become healed when some musician reminds you that you’re part of absoluteness and totality.

Do you know what your next album will be?

I want to do a Santana-only guitar instrumental record. I’m going to call it Shape Shifter. I’m going to put a sign on it, like a person with a microphone and a line through – No Singers.

And in Montreux in 2005, we did a concert with John McLaughlin, Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Stevie Winwood, Ravi Coltrane, my son, Salvador, and my band. We played “Imagine,” “A Love Supreme,” “One Love,” “Blowing In The Wind,” “Exodus,” “What’s Going On.” It was called Hymns To Love & Peace, and we DVD’ed it. We had maybe four hours of rehearsal the day before, and a tiny soundcheck. People said like, “That could never happen,” but it happened. It was like an army of incredible people. When you look at this DVD, it’s like Cirque de Soleil. It’s grandparents, parents, children, and all of a sudden it’s not important if you’re Jewish or Palestinian or Irish or Mexican. You’re going to be sucked into this vortex of beauty and feeling good. We did “In A Silent Way,” and Herbie and Wayne and Chick said, “We’re having a Miles moment. The last time we played it was with Miles.” So, as you can tell, there’s a lot of stuff happening with Santana that transcends the Mexican and the guitar player.

One of the greatest things I get from all this is to be in the same room with Mr. Desmond Tutu and Mr. Harry Belafonte. I want all this music to work with them for the betterment of this planet. We have a dream of creating like a tsunami wave of awareness that water, electricity, food, and education should be free – for the whole world. And it will be if enough people ignite that concept. Two hundred years ago, there was no electricity; there was candles and gas. But here we are. People forget that 75 percent of the world eats worse than our dogs eat in America. And a bathtub with hot water – are you kidding me? That would be like a supreme luxury.

But, for me, at this point in my life, after this CD does what it’s supposed to do, I’m already doing a somersault backwards into the unknown. I’m doing something that Bill Graham and Clive Davis always accused me, “That will be career suicide if you do that.” Well, that’s what I’m going to do, because I need to give birth to something that’s totally different from this beautiful trilogy that I just did – Supernatural, Shaman, and All That I Am. I need to give birth to a guy that I don’t even know yet. I’m really grateful to Clive and all the people for all their energy, but that’s done. I don’t know what it is, but I need to give birth to something that’s completely new but totally familiar.

When you’re collaborating with someone, you somehow always play something that fits without sacrificing your identity.

Well, I listened to what Miles said. He said, “First listen, don’t play. Then feel. And then whatever you think you want to play, don’t play that; play the stuff around it.” That’s pretty clear. Leaving space. There’s nothing worse than a person who doesn’t respect commas or periods. Same thing with music. If you hear a guitar player playing a million notes per second, it’s like a machine gun. Listen to Wes Montgomery, man, or Bola Sete, Gabor Szabo. The real ones, they leave space. So you can swallow the note. You can’t just keep shoving things in your mouth; you’ve got to chew and swallow once in a while. One thing all of us learned from Miles is space. Miles would convert 707 notes into seven. And when he hit you with those seven, it’s like watching somebody grab this whole mountain of charcoal and creating this beautiful diamond. You’re compressing and crystallizing.

But the goal is to complement the people you’re playing with; it’s not about head-cutting.

No, no, no. That energy is gone. This is not gunslinging. I’m still very competitive within myself. I do giggle knowing that if I open for the Rolling Stones or Sting or Prince or Lenny Kravitz, they’re probably going to have to change their set. But that’s okay, because if they open for me, we’re probably going to have to change the set. It all depends on how intense they are with hitting the majority of people with the songs. The times that I had to follow Stevie Ray Vaughan – which I did on his birthday in 1988 – I played music that was kind of like Pharoah Sanders and Coltrane. Like a big, beautiful hand erasing the blackboard with the equation of Stevie Ray Vaughan. It’s like a classroom. What he just played is written on the board. “That was a great lesson, man.” Then you erase the blackboard and start anew. It’s not like I’m dismissing him. I’m validating what he just did, but now we’ve got to start anew.

I invite all the great guitar players to look in the mirror once in a while and say, “Thank God I have my own identity.” Like Billie Holiday said, “God bless the child that’s got his own.” Smile and be happy with the gift that God gave you of uniqueness and individuality. This is not Wyatt Earp against the Dalton Brothers or Gunfight At OK Corral – that era is dead and gone. This is not the Olympics; this is not the NBA. If you have to triumph at the expense of somebody else, then it’s not music. I’ve been around enough to know that if you do that, you’re going to lose what God gave you. Real musicians complement. Messed up people compete. Know the difference. Complement and heal – that’s what real musicians do.

It’s like Keith Jarrett. He’s real happy with who he is; he doesn’t have to be Peter Frampton or Santana. He can get eight standing ovations playing ballads all by himself. He’s one of my heroes; I wish I could play the guitar the way he plays the piano. But at the same time, I honor the fact that he’s content with who he is. There’s a lot of great musicians who are not happy with who they are. I’m not a high-maintenance guy. The fact that I can be with Harry Belafonte, Wayne Shorter, Eric Clapton; I can talk to you, be in a magazine that I love – man, I’m in heaven. Money does nothing for me; drugs don’t do nothing for me at this point. To me, it’s closing my eyes and holding that tone.

Tones of a Master

The Santana Collection

Carlos Santana is ready to talk shop. “When I met Pat Metheny,” he says, “the first thing he wanted to see was how I held the pick.” He takes a large, triangular, fairly flexible Dunlop pick out of his pocket and demonstrates. Instead of the typical thumb and crooked index grip, he holds it as if he were picking a coin up off a table, with his thumb, index, and middle fingers all pointing downward.

Vintage Guitar: How did you first get introduced to Paul Reed Smith guitars?

Carlos Santana: He came to a concert in Baltimore – this wiry-looking kid. He said, “I have this guitar I want to send to you. If you don’t like it, just send it back.” I’d been playing Yamahas for a long time, so I played it, and it just had more bottom to it.

Did Paul start tailoring guitars to you?

No. Strangely enough, he changed. He wouldn’t make them like that anymore. For three or four years, he started making different models, and every time he’d bring a guitar, I’d play a few notes and say, “Nice guitar,” and give it right back to him. He got upset, and I said, “Well, it makes a nice lamp, but I can’t play this. It doesn’t sound good.” Finally, I got my [Yamaha] guitars stolen, so I asked him if he could make me a guitar like it. He said, “I don’t know if I can do that; it’s cost-prohibitive.” I said, “Here it is: either you find the mold of the guitar that you made like this, or I’m going to go somewhere else.” Sometimes people need that kind of motivation. And he made them exactly. So then he made a Santana Model.

For a long time, I played guitars and, just like with Boogie, I never asked for anything; I just played them and they fixed them. I never asked for an endorsement or money or anything. Once Paul made it, I found the [stolen] guitars; they were returned to me. But the blessing was, he learned how to do it exactly the same way. I think he did pretty good. I know he sells a lot of other models, but I don’t play those. They’re good for a lot of people, but they don’t suit my personality; the tones are too nasal. But this doesn’t sound like that. I actually did have to force him to find the actual mold of that thing, and he had to make a machine and make the thing.

We have a great relationship now. He understands that I play a Strat almost half of the concert, and he doesn’t have any problem with it. He’s going to try to make one like this, exactly the same body, with single-coils. If that happens, then I don’t have to take out the Strat. I just want the sound. I’m not looking to get into the arena with Stevie or Eric or Jimi or Jeff Beck. If you look at the Jeff Beck Model or the Eric Johnson Model, they all look the same – like a Strat. I kind of wanted my own identity, so that’s what he’s working on as we speak – seeing if he can make one with single-coil pickups and match that tone.

What made you start playing Strats more?

Just the tone. The configuration of it with the Dumble has a whole different texture. All my life I’m playing Gibson or Paul Reed, and it has a different kind of sound. These pickups are single-coil, so it has a different personality. I played a whole concert at Madison Square Garden just with the [’63 Olympic White] Strat – which I’d never done before. [Ed. Note: All of Carlos’ electrics are strung with extra-light Rene Martinez Big Core strings, .0095 to .043, pure nickel, made by GHS.]

Your ’54 looks incredibly clean.

I have two friends, the “‘Burst brothers” [Drew Berlin and Dave Belzer] from Guitar Center, and I had a jones a couple of years ago, because I saw pictures of Ritchie Valens with a brand-spanking new ’57. So Drew Berlin goes to every guitar exposition and trade show, and I told him to put something aside for me, and he got me a ’54 and a ’57 in mint condition. I don’t buy that many guitars, to begin with, but once in a while I like to take a deep breath and splurge on a real good one.

Before there was such a thing as Mesa Boogie, you still had that identifiable sound. What amps did you use in the early days? What were you playing at Woodstock, for instance?

One of those weird Gallien-Krueger solidstate amps, and it sounded horrible. But I just wanted it to be loud. Because Twins, you have to play so loud. I used to see Michael Bloomfield with the Electric Flag playing three Twins, and I was like, “Whoa!” I knew we were going to play in Woodstock at this big place, so I thought I might as well get something loud. After that, on Abraxas and all the other albums, it was basically just double Twins.

Did you stop using Mesa Boogies when you started using Dumbles?

No, I’ve been using the same amp that Randy [Smith] made for me since 1974. I use the Boogie and the Dumble together. It’s to get head tones, nasal tones, throat tones, chest tones, belly tones, cajones tones. For a long time, I was only getting the highs; I didn’t have the middles or lows. Now with the Dumble, I have middles and lows. That had a lot to do with Stevie Ray’s tone.

Do you record at high volumes?

Yeah. I record three amplifiers at the same time, which are the Mesa Boogie I’ve been playing since ’72 and two Dumbles, an Overdrive Special and a Steel-String Singer. I never had so much bottom in my life before.

What nylon-string do you use in the studio?

It’s the same one that I play on the road and in the studio [an Alvarez]. Just a practical guitar. I’m beginning to feel like Willie Nelson, because I’m putting holes in the wood, from playing them so much. – Dan Forte

This article originally appeared in VG‘s March 2006 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Peak collectibles from the 2021 Vintage Guitar calendar: a ’69 Dan Armstrong Lucite guitar and matching ’71 bass.

Peak collectibles from the 2021 Vintage Guitar calendar: a ’69 Dan Armstrong Lucite guitar and matching ’71 bass.