www.eastwoodguitars.com

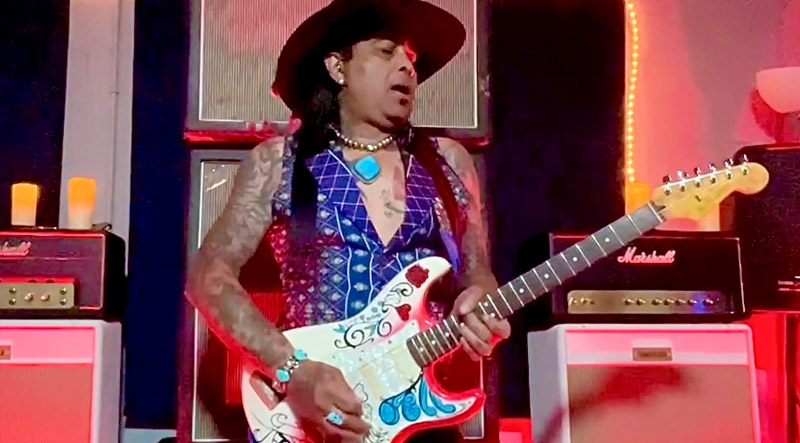

Thanks to über-tonemeister Carlos Santana, extended jamming, and the rise of overdrive, the ’70s gave rise to a solidbody trend that sought to achieve the holy grail of “sustain.” Using natural finishes, dense bodies, and even brass hardware, West Coast custom builds became a status symbol. But one notable axe in this wave was an import: the Ibanez Professional endorsed by Grateful Dead guitarist Bob Weir. Eastwood Guitars, having previously released a modern version of Jerry Garcia’s “Wolf” guitar, has resurrected Weir’s dot-neck version as the BW Artist.

In a side-by-side comparison with an actual 1978 Ibanez Professional, the BW Artist gets a lot of the details right. Like the original, it has a double-cutaway ash body with a beveled “German cut” edge and set maple neck. There’s also a 22-fret/24.75″-scale rosewood fretboard, gold hardware, and fancy headstock cut. Both the Natural and translucent Amber Sunburst finishes reveal the woodgrain, an important aesthetic of this earthy, back-to-nature epoch of guitar design.

While the original was a heavy plank with a big neck to grab, the Eastwood is more user-friendly – you still have a dense slab of wood and a large but (in this case) comfy D neck. Our tester weighed in the neighborhood of 8 pounds, 5 ounces – a walk in the park compared to chiropractor-ready ’70s Les Pauls or that ’78 Professional (another backbreaker was the $8,000 Ibanez BWM1 “Cowboy Fancy,” a Bob Weir reissue VG reviewed in the November ’16 issue).

Like so many solidbodies of yore, the electronics of the BW Artist offer few bells and whistles: two Dual Custom ’59 humbuckers with a Tone and Volume for each. The ash body and maple neck interact with humbuckers differently than a mahogany solidbody, resulting in a brighter tone than you might expect (a similar principle to ash or alder Telecasters with Fender’s WR humbuckers). Keep that in mind if you are expecting the mellow Les Paul warmth of mahogany tonewood.

Plugged in, the BW Artist plays well, with low action and a beefy, but quite likable neck. Don’t be surprised if you start chooglin’ out the chords to “Dark Star” or “Franklin’s Tower.”

With a friendly street price, the Eastwood is significantly cheaper than vintage Weir models, as well as being a modernized, highly playable reissue. Truly, the music never stopped.

This article originally appeared in VG’s September 2021 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.