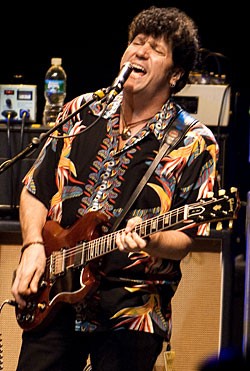

Photos by John Peden.

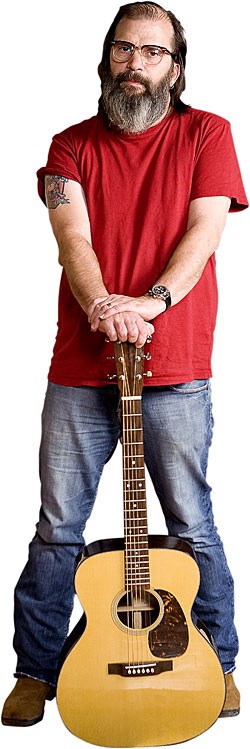

Though bandied about haphazardly and almost always inappropriate, when applied to the life and times of Steve Earle, the adjective “extreme” is not hyperbole.

The acclaimed singer/songwriter has survived 54 years of a life with peaks and valleys usually reserved for a soap opera. A high-school dropout, at age 14 he left his parents’ home near San Antonio and put food in his mouth as a working musician. Married (for the first of seven times) at the age of 18, he settled in Houston, worked odd jobs, and played music in clubs. Prior to celebrating his 20th birthday, he moved to Nashville, where, while still working day jobs, he’d write song, and play gigs at night backing Guy Clark.

After a few years in Music City, he bounced back to Texas long enough to form his own band, the Dukes, then returned to Nashville hoping to strike it rich. Under contract for music publishers Roy Dea and Pat Clark, he co-wrote the 1982 country hit “When You Fall in Love” by Johnny Lee.

With a hit on his resume, Earle decided to become to focus on his own material. From 1982 to ’85, he recorded a handful of rockabilly-styled singles, then in ’86 released Guitar Town, an outstanding effort that reached #1 on the country album charts. Strong releases followed in ’87 with Exit 0 and Copperhead Road in ’88.

In 1990, Earle released The Hard Way, followed by the live Shut Up and Die Like an Aviator in ’91. The latter was his last album for Epic; the label opted not to renew his contract, saying drug use was hampering his creativity. For four years after, he did little during a period he famously referred to as his “vacation in the ghetto” and included a stint in prison for narcotics possession.

In the years since, Earle his been prolific, and in May ’09 released his 14th album. Toss on the pile a book of short stories, an autobiographical book on his music, and two biographies by other authors, and it’s obvious Earle has not shied shying away from activity.

In 2005, Earle marked his 50th birthday by moving from Nashville to New York City, a place that not only more greatly embodied his bohemian spirit, but put him closer to a variety of cultures – a move the overtly political Earle deemed necessary in the sociopolitical climate of the time. “I also tried to learn how to surf, but it didn’t work out as well as moving,” he recently said in an exclusive interview with Vintage Guitar. “We were in Australia, and I took a bunch of lessons, but just fell off the surf board a lot. But I tried! I’m still changing.”

Since moving to New York, Earle has become close friends with Matt Umanov, a guitar maker, repair tech, expert on vintage guitars, and proprietor of the Greenwich Village guitar shop that bears his name. Whenever he’s in town, Earle hangs out at Umanov’s, buying “…more guitars than I probably should,” while in the second-floor the repair shop, Tom Crandall tries to keep up with the repair and setup needs of Earle’s 132 guitars.

During the interview, Umanov and Earle fondled an array of guitars from Earle’s collection, including one of his favorites – a late-’40s Martin 0-17. “I was looking for one of these, and Matt got two at a guitar show,” he said. “I think maybe it was Dallas. I bought both, and this one has extra sound that I’ve never heard in one. They all have that “bang” – the mahogany sound. But this one is a little clearer and a little more transparent. And players, when they get these, usually don’t let go of them.”

Umanov shared a theory about vintage guitars and the socioeconomic status of their previous owners. “Even with the cheapest Martins, people tended to take better care of them. Why are so many more old Gibsons more f***d-up than old Martins? Two reasons: one, they weren’t built as well; and two, people who tended to buy Martins were people with more money, maybe a bit more education and/or manners. I firmly believe that. You’re more likely to see an old Gibson that got left in the back of a pickup for 43 years.”

Our discussion begins there…

Steve, what steered you to Gibson acoustics?

Steve Earle: Well, I bought my first Martin, a pre-war D-18, for $150 from under a bed in San Antonio. Someone put a big, ugly hillbilly pickguard on it. Even though it sounded like a million bucks, the action had gotten really high because it hadn’t been taken care of. I tried and tried to keep it in tune once I got a capo on it, and I couldn’t do it. So in 1970, I traded it for an Alvarez Yairi – I made the trade because the Alvarez worked, and I had a gig. I made my living playing the guitar five or six nights a week, mostly in restaurants, and I had to have a guitar I could play.

I played that Alvarez until I got to Nashville in 1974, when I saved up and bought a ’57 Gibson J-45 for $250 from George Gruhn. Though it seemed like an outrageous amount of money, Gibsons were the only thing cheap in George’s shop.

From a collection of more than 130, this 1890s Martin 1-28 is Earle’s favorite instrument.

Matt Umanov: I still have my ’43 D-28, which at the time I bought it had already been stripped, repaired, and refinished. I paid $155 for it in a pawn shop, and that was top dollar in 1963.

SE: My deal was I hitchhiked everywhere, so I needed a guitar with an adjustable truss rod. That’s why I became a Gibson player – the adjustable truss rod, period. It wasn’t that I knew anything about them, it was just that people told me I could fix it if what had happened to the Martin happened to my Gibson, which isn’t true, necessarily.

Today, I’ve adjusted the necks on my Martins a couple times, but I’m still nervous about it. I still get Tom [Crandall] to do it for me. But I’ve done it – I have a wrench!

But the 0-17 has something in the top-end that mahogany Martins don’t normally have. They all have it down here (strums the bass strings), but most, starting with the B string, start to disappear a little compared to the other strings. They’re just a little more opaque-sounding, normally. This one has that extra treble that I normally associate with spruce tops. There were two [in Umanov’s store] a year apart – a ’48 and a ’49.

MU: I know the 103 prefix is very late ’40s or early ’50s. Number 100,000 is very late ’40s, and this is 103, so…” (Umanov turns the guitar around and sees it has a thin brown stripe running cross-wise.)

SE: That’s interesting… I never saw it before. It’s just a weird line in the wood – straight across.

MU: It’s in the grain. It’s proximity to a branch. This back would not have made a grade-18 guitar. But for a 17 – no problem.

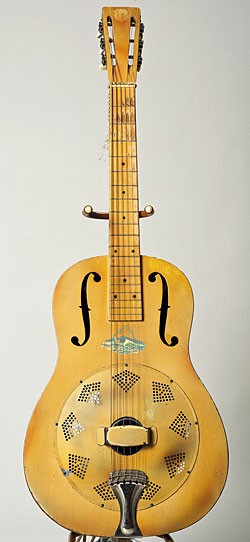

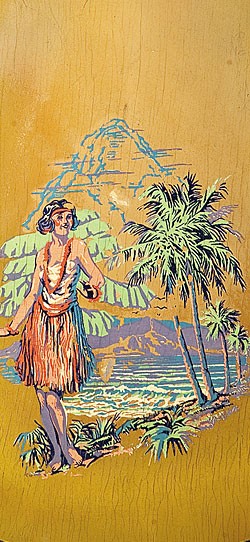

SE: I bought [a 1929 National] Triolian from Matt on the condition that I’d never remove the cord – the rope strap – ever. I think I have a contract that says that (laughs)! I bought it same day as the 0-17.

MU: You know what I love about these Triolians? The design. She’s got a ’20s flapper hair-do.

Who used a cord strap like that? Was it Woody Guthrie?

MU: Everybody used cords like that – it was the only guitar strap you could buy.

SE: Most of the guitars associated with Woody never belonged to him. The Woody Guthrie Martin model [is based on an] 0-17 that belonged to Will Geer’s wife, and Woody used to borrow it and disappear and get drunk. He’d finally f**ked it up so bad that they just let him have it. His J-45 was borrowed from somebody. He was hard on guitars, and most of them he did not pay for. The famous Southern Jumbo, I don’t know about. I think the Southern Jumbo might actually be one he purchased, because it’s the guitar that he’s playing in the pictures and on his radio show. He was an organizer, but had a radio show in L.A., so he might have bought that one. I just know about that 000 because I tracked it down after reading the Joe Klein book Woody Guthrie: A Life – there’s a story in there about him borrowing that guitar that came from Will Geer. That’s one of the two “This machine kills Fascists” guitars. The original is a nylon-string, and I’ve never been able to figure out if he owned it.

MU: I’ve always thought it looked like the typical Paracho guitar; Paracho, Mexico – the famed guitar-making town.

SE: I’ve got a bajo sexto that came from there. I’ve had several guitars from there over the years – the generic gut-string guitar. There were those, and there were tons of those Goya gut-strings around, too. Joan Baez used to play one, and you know who had one? Bromberg. My dad wanted me to have one, but I wanted a Stratocaster.

The shape of this neck [Triolian] is so cool – somebody played the heck out of it. I think the cone has been replaced, at least it looks kind of shiny. Tom would know, he worked on it. I think I only have one National with the original cone. I think my mandolin might, though.

There’s a lot of Matt Umanov in that mandolin. I bought it from George Gruhn. Actually, a girlfriend bought this for me from George, for my birthday. It was always the best one I ever ran across. Then all the things that made all the other ones unplayable started happening to it. It’s one of the most ill-designed instruments in the history of mankind, and Matt has done a bunch of surgery. This tailpiece started to self-destruct, and it started to go out of tune; it was buckling under stress. A jeweler friend of Matt’s, Combat Shelley, fixed it.

Also Matt, you did a modification on the neck-stick – I didn’t even understand it. You fabricated something out of plastic and metal parts into where the strap-pin (end-pin) holds the whole ****ing thing together…

1870 Martin 0-28.

1927 Martin 5-21T

1931 Martin C-2 conversion

’37 Martin 000-18

MU: That’s one of the few times in years that I’ve hit the workbench myself. There was a lot of empty space in the end of the dowel-stick and the whole thing was loose, so I fabricated some wood, metal, and plastic.

SE: Making a mandolin sound sort of in tune when you’re playing it is an illusion in the first place, you know? I mean, they can’t be in tune – guitars aren’t really in tune, either, but mandolins are notoriously out of tune. In Italian, mandolin means “out of tune,” right? However this one was always more in tune than they usually are, but then it went south on me.

I used it on the Washington Square Serenade album, and wrote “Red Is the Color” on it – my Yank Rachel impression. I’ve had the mandolin since ’97, but didn’t get it on a record until last year. I sometimes feel guilty about owning as many instruments as I do.

You shouldn’t feel guilty – you use a lot of guitars in your live shows.

SE: Yeah, but I don’t take old stuff on the road. I like s**t that works on the road. I’ve fired several guitar players [who] got the “old Silvertone” bug or something. [Guitars like that are] not professional equipment. I like new guitars.

What are some amps that you like?

SE: I have some really cool vintage amps, but I won’t take them on the road, either. You know what I use onstage? Peavey Classic 50s with eight 10s. I’ve blown up one Classic 50 in the 15 years I’ve used them, and that was because I shoved it over. There’s something about them – they sound kind of real open and Class A-ish if you use them with eight 10s rather than four. That’s what they like. It’s stupid loud, but sounds better than four 10s.

My main amp in the studio is a Vox AC50 amp, and I finally got one that belongs to me. Ray Kennedy had one I used on most of my records for the last 10 or 15 years. It’s not really a class A amplifier. The one I’ve got now is one that Charles Sexton found. I’ve known Charles since he was about nine, and he finally came in off the road and said he didn’t need two anymore. I run that through TKLs – that’s what they were designed for, and you shouldn’t run them through anything else.

I like 10s, but ohmage is everything. Unless it’s a piece of s**t, whatever the guy built it to go with, he probably did it for a reason. The math is important when it comes to coupling a speaker – especially with really powerful amps.

Which of your amps stay in the studio?

SE: That AC50, a killer ’60s Fender blackface Super… I like 10s, period. I also have a small blackface Vibro-Champ and a Deluxe that’s killer. I also bought the first one of those ’56 Deluxe reissues. That’s my main New York City amp because it has a small speaker and it’s light enough to carry on the subway. So it’s practical, and won’t blow up; I own three Fender Pro Juniors, which are great, but I’ve blown up two while sitting in with somebody and thinking, ‘I’ll take a little amp,” then everybody else is louder than I am. So the Deluxe is just a little louder and has a killer tremolo. (Earle takes out a Martin Style 1-28 and starts to tune it.)

This is my favorite guitar.

MU: That was my absolute favorite guitar, and might still be. I’ve known that guitar for over 35 years. It belonged to my friend, Doris, who got it in the late ’60s. When I saw it, I knew about size 1 guitars, but this one stole my heart. She sold it to finance a piano.

SE: She sold this and a C-2 conversion Matt built, and I bought both. Matt built David Bromberg’s F-7 conversion, too – that’s the guitar Martin patterned their M-style guitars after in the ’70s, right Matt?

MU: Right. I made Bromberg’s F conversion. I made one or two others over the years, but I also made two C-2 conversions, one of which was for Doris. I built hers in ’71.

SE: It’ll settle in a minute, hook up, and freak you out. It’s got some not-going-anywhere cracks in the side Matt says have been there for years, but they just always make me nervous. Is this one opening up?”

MU: No, that’s been there for 35 years. This guitar is from the early/mid 1890s. It’s rock-solid, and it’s no featherweight, which is not what you expect from a Martin of that period. Well, from that period yes, but three or four years later? No way! They were made of tissue paper by the late 1890s and early 1900s. My guess is the bridge was replaced by Martin in the 1920s.

SE: I have this theory that guitars need to warm up when you first play them, especially archtops. I was playing an L-5 in the store and Matt told me, “You need to play it, then wait. Because all those components are mechanical and they need to hook up.” Since then, I’ve noticed that’s also true of flat-tops to a certain extent. They loosen up or something. For lack of a better word, there’s like a harmonic convergence.

’48 Martin 00-17

’48 Martin 0-17

’51 Martin 0-18

’53 Martin 5-18

I recently fell in love with guitars all over again. I thought I was through buying, but since I got out of jail, I started over. A lot of it has to do with that I put about a million dollars’ worth of guitars in my arm. And I tended to buy new guitars – I own two Epiphone Lennon Casino reissues which have been my main stage guitars because I don’t have to feel guilty about playing them. They’re still kind of an investment because they were a limited edition – and they’re well-made instruments. I concentrated on – and still buy – stuff like that. I’m bad about coming in and buying new Martins that there’s not going to be a ton of. They’re something you can get into that you’ve at least got a chance of being worth more money in the future, and you can play them. You don’t have to feel like you shouldn’t touch them.

MU: It’s also true that just about everything that comes out of Martin is really good. And every so often you pick up one that’s like… it’s right there from the beginning and you know that over the years it’ll become greater than the sum of its parts.

The Martin Authentic D-18 is built in the traditional style, with hot hide glue, a steel T-bar non-adjustable truss-rod, and other exact appointments. What do you think of those?

MU: Those are great guitars, they’re wonderful.

SE: I’ve been thinking about getting one of those hide-glue guitars because the only mahogany Martin I own is a 12-string. No, I take that back; I have a ’30s 000-18 – another guitar I got from Matt. And I have a ’69 D-18S – the “folk scare” guitar. So I have more than I thought. And I’ve been eyeballing a really nice ’64 D-18 in the store.

The Martin Clarence White with the big soundhole is an especially good-sounding guitar.

SE: You know why Clarence White played a guitar with an over-size soundhole? Because if you pick as hard as Clarence did, you wear right through the soundhole. They tend to come apart right where they put the trim in – and it did – and a guy just trimmed it out uniformly, making an over-size soundhole. It was the ’60s, and I’m sure somebody – probably Clarence – said “Oh, it sounds better” (laughs)!

MU: Right. It’s like people think if they buy an Eric Clapton model Martin they’ll sound like Eric Clapton. What doesn’t come with the guitar is 10 of [Clapton’s] (wiggles his fingers).

SE: Yeah, and people are afraid to buy my artist model, because they’re afraid they’ll become Communists!

When I started buying these Martins, we were down in the shop and Matt gave me his “size 1 lecture,” which is, “This is where it all starts…”- the idea that this particular model is where the technology developed. So I decided I wanted one.

MU: Size 1 is Standard, that’s the Martin name. An 0 is Concert, 00 is Grand Concert. Size 1 is called Standard because it is the standard from which all else was extrapolated. Steve’s a wonderful guitar – it’s my favorite Style 1. Doris bought it at a pawn shop called Unredeemed Pledge.

SE: I’ve had it almost two years. I tune it to D or just above D because it’s so old and sometimes I’m gone a pretty long time. I was just on the road almost a year, and I left it in Nashville, tuned down, all that time. I just brought it up to the city.

If you drop any guitar a whole tone, you’re releasing at least 20 percent of the string tension, maybe 25 – a huge amount, anyway. It’s almost the same as removing the strings.

The funny thing is when I get it out after it’s been tuned down like that, it really sounds good. But when I tune it up to pitch, it’s like “Now I remember why I bought this guitar.” Because they want to be at concert pitch. That’s what they were designed for and that’s when they perform. It’s a ****in’ great guitar. I’ll use this guitar so much on the new record.

MU: It only occurred to me recently, when this guitar came back, that this bridge is not original, and is in fact a 1920s Martin factory bridge. You look at enough Martin bridges and you see how they changed the contour, shape, and form over the years. Because different guys were making them; you know, one guy makes bridges for three years and 11 days, and then is put on something else and a new guy makes the bridges. Each man had a style.

SE: Some people would call this a parlor guitar, but that term pisses me off because it makes no sense. I don’t understand what a parlor guitar is supposed to be, you know? I don’t think people bought guitars to have in their parlors. Pianos, yeah. One of the main reasons I’m not a piano player is you can’t hitchhike with them. That’s the cool thing about guitars – they’re portable. That was the whole deal at one time, and that’s why they didn’t go away. Chicks dig them, too. I’m from Texas and I didn’t play football, so it was football or this, and I wasn’t very athletic…

’74 Martin 000-45

1937 National Model O.

Back of the National O.

1951 National 1155

What pickup system are you using?

SE: Tom used to install the Fishman Matrix I in my guitars, but that system has been superceded by the Matrix Infinity. It comes with soundhole-mounted controls that are just bothersome to me and one more thing to break or come loose – I preferred the simplicity of the earlier Matrix I. As it turns out, Martin’s Thinline Gold Plus Natural 1, which is also made by Fishman, is the same as the old Matrix I, so that’s what Tom’s installing now. I run it through the Fishman Aura mixed 70 percent Aura and 30 percent Natural 1.

I prefer the Aura to using a blended system – i.e. a microphone inside the guitar and a saddle pickup blended together by a stereo pre-amp. The blender system works, and it sounds much better than a pickup by itself, but the weakness of it still is that saddle pickups, and internal microphones, lack air. The attack is too “on top” – without the natural delay you get when you put a microphone in front of a guitar, and it takes a nanosecond for the sound to get there.

The blended system acts like an electric guitar – like an electric guitar plugged right into a stereo – because there’s not that delay, and that totally changes the way you play. The Aura puts the air back into a live performance.

The other cool thing is that even if you’re using floor wedges, you can put exactly what the audience is hearing back through the monitors, and you actually get to enjoy what your guitar sounds like. With the blender systems, you couldn’t put the microphone back through the monitors.

Live, you play a Martin M-21 Steve Earle signature model. What makes the guitar different?

SE: I am completely and totally queer for Style-21 guitars because I’ve always liked the “plainness” of them – like 18-style mahogany models are plain, but have rosewood back and sides. I own three M-size guitars that are fancier – a 42, a 36, and a 38. I also have a 000-45S. I’ve got the fancy guitars because they’re collectible, and they’re really good. But I really like plainer guitars, and I have this thing for the style 21.

I’m the first to admit it may have absolutely f***in’ nothing to do with reality – and it’s totally one of those things a guitar player will say – especially those as bad as I am – but I’ve always felt more comfortable on rosewood fretboards.

MU: It was Steve’s idea to go with the M-21. I gave him some technical details, but we wanted the best sound for the least cost possible, and that will be a Style 21 in the tradition of the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s. My own personal guitar, which I’ve had since the ’70s – is a 000-21 from the ’50s – I love it. It’s my guitar. So Steve and I agreed that the 21 was the way to go, with tortoise binding and some other things like peghead shape, for example.

SE: The peghead shape was the only major variation from the period that the Style 21 appointments came from. Because in the ’50s and ’60s they were really round because the sanding or shaping jig had worn down over the years. Ours is a late-’40s shape.

The main reason I went to this body shape was the depth. Hanging my arm over a f***in’ dreadnought was ergonomically kicking my old ass. It was hurting my shoulder, and the inside of my arm. I used to think it was silly when people thought there was one size of guitars for fingerpicking, and one size for flatpicking, because I fingerpicked on a dreadnought just fine, you know? But I also stood on the hoods of station wagons going down the interstate and did some other s**t that was bad for me!

MU: It comes together visually. And we really hit it, even with the pickguard – it’s the best-looking pickguard they have. Little things, like the purfling around the top and the soundhole… I wanted certain stuff. When it came down to the internal stuff, I went with what Dick Boak suggested, coming from the sales realm.

The guitar has forward-shifted bracing. What is that?

MU: It refers to the original 1930s top-bracing pattern Martin devised for 14-fret dreadnoughts. The X is closer to the soundhole than it was after 1939 or so, when they figured out that moving the braces back some would be stronger structurally, so they abandoned the original forward pattern. It’s very soughtafter today in older guitars, and new custom Martins ordered by guys who are convinced that a guitar with forward-shifted bracing sounds better.

So many times, I have laid a stack of $100 bills on a table and said to anyone who claims to know the difference, “I will now find you 10 guitars – half with and half without forward-shifted bracing. Match my money, and guess right more than half the time with a blindfold on.” They won’t do it. You know why? Because it’s a load!

How receptive was Martin to these nuances?

MU: Oh, totally! Dick is the best! He is more responsible for Martin’s public image having improved exponentially for the past 20 years. He’s a wonderful guy, and he’s smart.

Front of a 1928 National Triolian

Back of a 1928 National Triolian

’51 Gibson CF-100

This ’65 Gibson J-100 was ordered from the factory with two pickguards – one for a J-100 and a J-200.

The restraint with the M-21 is what’s so great, and that comes from the combination of what Steve wanted and my knowledge of what can be done, what can’t be done, and what should be done.

SE: Yeah, I wanted to keep the price as low as we could on a solid-wood Martin. Matt sells them for the mid-$3,000s. Nowadays that’s not expensive for a solid-wood acoustic – especially a Martin.

MU: Steve and I had a great time collaborating. I’m of the school that the right idea will come to me at the right time. Sometimes, I’d let the paperwork sit on my desk for two or three weeks. Then, I’d pick it up and say, “Oh, yeah… that part, it should be done that way.” So it was months before we had all the details down. It could have been done in an hour, perhaps, but for us it was months talking back and forth, and back and forth with Dick.

When Steve and I signed off, we knew it was going to be a great guitar. But when the first ones came, we were so happy with them – and proud. And it really is more than the sum of its parts, I think. You pick it up, you say, “Wow! It looks like there’s not much here.” And there’s not. But it’s a lot of small nots that add up to something great, you know?

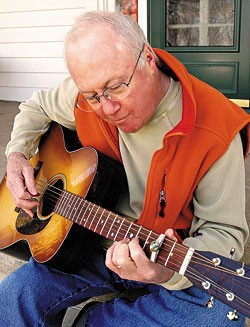

What electronic tuners do you like or use?

SE: You know, I finally figured that I needed to learn how to tune a ****ing guitar again, because I’ve toured so much at a level where I had a guitar tech handing me tuned guitars every night. It wasn’t until 10 years ago, when I made the bluegrass record, that I was back in the realm of people who played a lot better than I could. And one reason they did is their ears were really great. All of a sudden, I had to listen. And I’m into that vintage thing. My wife says I make records like a civil war re-enactor cause I use all this old gear, you know? But bluegrass, the way we do it, works better when you play it around one microphone.

Yeah, the bluegrass thing – Norman Blake won’t use a tuner. That’s a little hardcore. The tuners I own clip directly to the guitar, and work pretty well.

Do you tune to the rise or fall of the note?

SE: Out of habit, I tune to the fall, because if you’re ham-handed, which I used to be, you have to wait to get a true reading. I mean, it’s maybe not sharp enough at first that you can hear it, but the tuner can definitely hear it.

You keep them well tuned – sometimes without using a tuner.

SE: Having a guitar tech is most of it. I mean, I do end up having to tune them myself sometimes. But 10 years ago, I couldn’t have done that. I’d sort of forgotten how to tune, from having a crew with roadies and guitar techs. But I find it necessary to re-learn as much as I can. Not just in case I have to, but because it’s good for me. It’s like remembering what I am and how I got to where I am – just going back and sort of remembering life for all it is.

You know, when I’m coming out of the subway, I always give anybody sitting there buskin’ at least a dollar, because there, but for the grace of God… And I’ve busked. I can take one of these guitars and I busk. If I was going to take one, it’d probably be my M-21 sunburst, because I think it would hold up. Until recently, I would have been really embarrassed to talk to any magazine that was for and about guitar players. But you know what? I’ve decided recently I’m a pretty f**ing good guitar player! But how did I get that way? And how did I get to be a pretty good songwriter? Because I have a huge amount of respect for tradition, and a huge amount of respect for history. I’m very, very interested in where I came from and where all this came from. But I’m also not afraid to throw all that out the f***ing window every once in awhile, and I don’t let somebody tell me “Because that’s the way it is” and let that always stop me, you know? I accept some people’s authority that things are the way they are. I’m still here, I’m still alive – literally – because of the very act of unlearning behavior that was really, really, really ingrained. And now I’m re-learning a lot of stuff, going as far back to when I was 14 or 15 and almost had “C.F. Martin and Co., established in 1833” tattooed on my back after I bought my first Martin. My girlfriend talked me out of it, and then I became very anti-Martin for a long time. In fact, anybody would probably have assumed that if I ever had an artist guitar it would be a Gibson, because I’ve been associated with them for such a long time.

Speaking of Gibsons, I have a ’65 J-100 that was ordered from the factory with two pickguards – one for a J-100 and a J-200. Matt bought it from the original owner at the Spartanburg (South Carolina) guitar show. I don’t know who owned it, but his initials, CP, are on the guitar. You know the spaces between every fret that are not filled with one of those crowns? He inlaid something in each one, and they’re all different. It looks like Leonardo da Vinci threw up on it. There are crescent moons, stars, his initials, and the words “peace and love” laid out in this f***in’ Masonic-looking [way] that’s unreadable, but it works. It’s like Donovan meets Eddy Arnold. When Matt saw it, he said, “Steve Earle!”

There are only a few Gibsons I’m still in the market for. One is a J-35, and there’s a really good natural-top early-’40s one in the store I’ve looked at real hard. I haven’t jumped on it for some reason, but I want a ’30s version rather than an early-’40s. I guess I associate J-35s with the ’30s. I’m after the one where the top has three tone bars rather than two. And I’ve got a really good CF-100, but Matt’s got another one, and I may buy that. They’re really good guitars when they’re good.

What do you think your future might hold, in terms of guitars?

SE: Well, I haven’t been all that interested in electric guitars; hadn’t bought one in a couple years, and then I bought two lately. So I don’t know what’s gonna’ happen!

Martin M-21

Dan Digs In – The Martin M-21

No guitar smells as good as a new Martin, in part because they use Spanish cedar kerfing to connect the sides of the guitar to the top and back.

The M-21 Steve Earle signature model is a joint effort between the two-man team of Steve Earle and Matt Umanov, and of course, the famed manufacturer.

The M-size came into being in the mid 1970s because Martin was aware of several vintage Martin F-size archtops (built from 1935 until ’42) that had been converted to flat-tops in the ’60s by luthiers including Umanov, John Lundberg, and Eugene Clark. The F was similar in shape to Martin’s 000 models of the same era, but larger and slightly thicker from top to back. They were even larger than a dreadnought (same length, but wider), and in the conversion created a new size – the 0000.

Umanov’s conversion was of particular interest because he didn’t retain the F-model’s 24.9″ scale. Instead, he used Martin’s longer 25.4″ scale, and installed longer necks to accommodate it. He anticipated that it would have the power and tone of the Martin Orchestra model (OM), which it did. This conversion became famous in the hands of David Bromberg and is the guitar Martin patterned its M-style guitars after, beginning with the M-38 in 1977.

The OM debuted in 1929 and was Martin’s first “modern” guitar – i.e., designed specifically for steel strings, with 14 frets clear of the body and using the 25.4″ scale that would also be used on the dreadnought models to follow a couple years later. By ’34, the OM was renamed 000, as the earlier 12-fret model was discontinued, and its scale length was shortened to 24.9″, leaving the dreadnought as Martin’s only long-scale guitar for years to come. Umanov points out, however, that 14-fret long-scale 000-18s have been seen as late as mid 1935.

The OM body looks like an original 12-fret 000 that was held fast in the lower bout while being squashed 1″ shorter length-wise, thus bulging wider in the shoulders. The soundhole and bridge are moved forward to accommodate the longer neck and 14 frets clear of the body. For that to happen, the X-brace also was moved forward, and is known as “forward X,” “advanced,” or in Martin terminology, “High X” bracing. Martin uses this bracing on certain vintage reissues, including the M-21. By ’39, Martin moved it back from the soundhole toward the bridge, probably because the heavy-gauge strings used at the time wreaked havoc on the bridge area. Today, early advanced-braced guitars are highly collectible.

The M-21’s braces – top and back – are thin (5/16″) and light, adding to the guitar’s sparkly tone and fast response. The top braces are scalloped

The M-21’s shoulders and lower bout are the same width as a Gibson J-35 (115/8″ and 16″), but the waist is 1″ narrower (93/4″ vs. 103/4″). Of equal importance is the fact that the M is also considerably thinner from top to back (31/4″ tapering to 41/16″ vs. the 4″ to 5″ taper of the Gibson). For many players, the narrower waist lets the guitar nestle lower in the lap, and is easier to reach over with the picking arm. No other Martin is the same size. The closest is the Gibson J, which is the same shape, but as deep as a dreadnought.

It’s unusual for a guitar in the M-21’s price-range to come with Waverly tuners. It’s a classy touch. Its overall design is simple, elegant, and handsome, in the Style 21 mode preferred by Earle. And its loaded with little touches that only an expert like Umanov would be aware of, such as multi-layer tortoiseshell top binding (the outer color against the inner plys gives a “dark” look specific to Style 21. There’s also tortoise/single white back binding. Other Umanov design touches include;

Dan Erlewine strums the Martin M-21.

The M-21 gets Martin’s “pocketed” frets, which mimic a bound fretboard.

The M-21’s old-style peghead decal.

Back of the peghead, with no diamond volute.

|

| Top | Backs | Sides | ||||

| M-21 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.1 | |||

| J-35 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.7 | |||

| AJ | 3.6 | 3.7 | 2.7 |

|

This article originally appeared in VG‘s July 2009 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Steve Earle : Christmas Time In Washington