Ivan “Lord Bizarre” Symaeys with a 1965 Wandré Bikini and an assortment of guitars. All photos by Joe Bigley.

When most Americans think of Belgium, it’s usually beer, chocolate, or waffles – all commodities that deserve their excellent reputations. Although the people in its Flemish- and French-speaking regions do not always agree on things, Belgium is a friendly little country with a rich, diverse culture. It benefits from being centrally located in Europe and most Belgians speak very good English freely with foreign visitors.

Leuven is an attractive university town about 10 miles east of Brussels. Its academic and medical institutions date to the 15th century or earlier. The sights, lively night scene, and old-world charm would be enough to recommend a visit, but for those with a passion for unusual vintage electric guitars it holds an extra treasure – Lord Bizarre’s Electric Guitar and Amp Museum.

Ivan Symaeys is its proud proprietor. An electronics technician by trade, he operates a repair shop called Rock, where he works on guitars, amps, PA gear, and old juke boxes. A serious collector of kitschy old arcade games, gas pumps, and juke boxes, he is an imposing figure with long, dark hair and a bushy beard, reminiscent of Bob “The Bear” Hite of Canned Heat or the caretaker in the Harry Potter movies.

Symaeys immediately warms up in any conversation that begins with guitars. He’s funny, very knowledgeable, opinionated, and like many Europeans, fascinated with “Americana” – especially old rock and roll memorabilia.

As a teenager, being handy with electronics and having no money, in 1969 he decided to build an electric guitar. He carved a body, grabbed a telephone microphone to use as a pickup, and fashioned frets out of copper wire. He copied the fretboard dimensions from a friend’s guitar but got the measurements wrong, so it’s only playable up to the fifth fret. It looks like something out of the Flintstones, but it’s a nice accomplishment for a 13-year-old. He used a converted FM radio as an amp, but after growing tired of his rig’s distorted tone, ordered a Fuji electric guitar from a catalog and began rocking with friends in the garage. Years later, his time consumed by electronics school, he became fascinated by electric devices, and started repairing juke boxes. Business grew to include other electronic equipment, including amplifiers.

![The main hall of the museum. Some pieces that appear to be modified (such as the four-pickup model [LOWER LEFT]) are actually stock. If Lord Bizzare finds an album showing one of his guitars, he displays it near the instrument. The main hall of the museum. Some pieces that appear to be modified (such as the four-pickup model [LOWER LEFT]) are actually stock. If Lord Bizzare finds an album showing one of his guitars, he displays it near the instrument.](/wp-content/uploads/3832/02a-bizzare.jpg)

The collection is precariously assembled throughout the house – watch your step! Lord Bizzarre intends to expand so his display area can do justice to these treasures.

In 1995 he began to collect guitars in earnest, buying first a used Gibson SG, then an Ibanez Rocket Roll II, followed by others in rapid succession. Before long, gathering guitars became an obsession for Symaeys, and he began to focus on obscure brands, especially from Eastern Europe. Each new axe presented a challenge in figuring out just what he had in front of him, and what made it tick – and there were electronic surprises galore! Popular Western brands such as Fender or Gibson don’t hold his interest because there’s little to discover in terms of their origin, history, or how they work and sound.

In his early days of collecting, Symaeys bought any unusual or interesting electric. Lately, though, he has become more selective. Most pieces he obtains have “issues” and he claims to not pay a lot for his guitars, saying doing so would take the fun out of it.

Symaeys’ collection today includes about 350 guitars and 50 amps from the 1950s to the ’80s. About 200 are on display throughout the building that houses the museum, and the rest await restoration.

Symaeys is a fountain of information, and while a visit to his museum is a treat, it’s also an education. He enjoys showing his collection and offers commentary about favorites or any piece an observer might point out. The collection has gradually overtaken his entire three-story house. He doesn’t play much these days, but he knows the story behind each guitar and regularly caresses each, “So they don’t feel forgotten or orphaned.”

The Museum

After eight years of serious collecting, in 2003 Symaeys opened the Lord Bizarre museum on the top floor of his house. A low-key affair, surrounding streets bear no signs pointing out its location. Nor does the building itself. He thoroughly enjoys playing host to visitors, but Lord Bizarre is a working man, and simpley doesn’t have the time to indulge the leisurely curious bouncing in off the street day and night! He doesn’t advertise the museum; you won’t find it in the phone book or any tourist guide book. People find out about it by word of mouth.

The main hall of the museum. Some pieces that appear to be modified (such as the four-pickup model [LOWER LEFT]) are actually stock. If Lord Bizzare finds an album showing one of his guitars, he displays it near the instrument.

The museum is “space challenged” and can accommodate only a few visitors at a time. When the front door opens, visitors are greeted by guitars hung in two rows on the wall in the entrance hall – beginning within inches of the door! Symaeys greets guests amidst a wealth of eye-catching Japanese guitars with names like Zimgar, Teisco, and Kay, most in oddball shapes or colors with funky appointments – green guitars with red pickguards, zircon-encrusted pickups, switches, toggles, and controls. Many bear no names on their bodies, headstocks, or anywhere else. A few have a single pickup that slides into any position between the neck and the bridge. Or there’s a set of spacey guitars in three different metalflake colors with different knobs, pickguards, or necks. Fret markers range from dots to bars to triangles, some in colors. Some mark only two positions on the fretboard, while others mark every position. There are strangely-shaped headstocks of various sizes, many striped or mottled with pearloid. Some fretboards are made of mysterious woods, others are simply painted. And a visitor sees all of this before they get to the actual museum!

Getting to the formal museum section requires traversing two sets of stairs. Guitars line the staircases and each landing, perched alongside amps, toy-related guitars, and rock memorabilia. At times, one literally has to watch their step to avoid an instrument! The host realizes it’s a bit anarchic and is planning an addition to the top floor to get better organized and provide more display space.

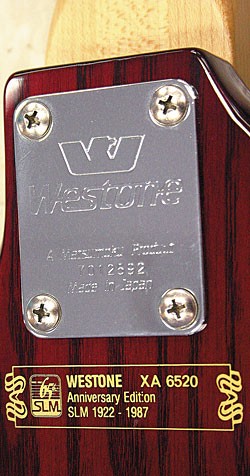

The collection is roughly grouped by country of origin; the first set is comprised of Korean guitars, mostly knock-offs of Gibson instruments. Symaeys explains that many manufacturers started building very low-end cheesy instruments, but with time and reinvestment in their product, the guitar became very playable. Samick (and its Hondo brand) falls into this category. Examining the early models versus the later ones reveals better body contours, components, and fit and finish. One example is a beautiful Samick inspired by the Ampeg Dan Armstrong plexiglass model. Like the original, it’s a weighty axe!

Some of the forlorn instruments await parts so they can graduate to “museum display” status.

Guitars made in the now-defunct Soviet Union appear next. They are particularly aggressive-looking and loaded with switches and built-in effects. How could anyone select a specific setting in the face of such a multitude of switch permutations, levers, buttons, and dials while playing a gig? Their vibratos look to be adapted from a ’50s Buick instead of a guitar, and on some, the bar is mounted in the center of the bridge, protruding at such an angle high enough to damage one’s forearm during frenzied playing! Most of these specimens, Symaeys says, are not particularly well-made, and when the built-in effects actually work, they tend to sound lousy. An exception is the exotic “Roden” bass (a Russian-language tribute to sculptor Rodin). It has a unique, elegant design.

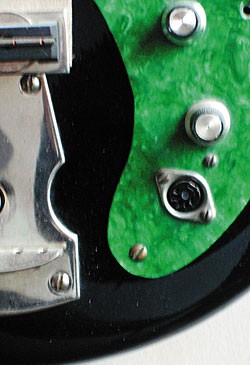

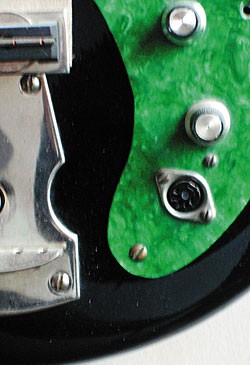

Several factories cranked out the same model guitar. This explains variations on a basic theme; one interesting feature of the Soviet-bloc guitars is the use of DIN plugs in place of the standard 1/4″ phone jacks (some even use banana plugs). The use of DIN plugs shows coordination, or least interplay, across the guitar industry behind the Iron Curtain, or at least that they copied what they could get their hands on. Iconic American goods like electric guitars were difficult to obtain in the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Interestingly, the guitars of this era are not clones of popular U.S./U.K. models, which suggests designers did not have had actual specimens of Western instruments to copy. Photographs, perhaps, but not actual guitars.

To be fair, companies behind the iron curtain probably did not have access to the best building materials and may not have done research and development on a consumer luxury item like an electric guitar. They used what they had, and these components didn’t always withstand the test of time. In Lord Bizarre’s museum, many tuners, metal parts, adhesives, and woods have corroded. Certain cracks each year get longer and deeper. One pickguard is slowly dissolving into a sticky goo. The bridge of one acoustic has become so misshapen the strings have popped, one-by-one, while the guitar has remained on a wall hanger. But the blemishes are part of the real-world appeal of this collection. These are not pristine instruments that have spent most of their lives under a bed. They were played, and played hard, by musicians creating spirited rock and roll in countries where doing so was effectively breaking the law. There is a lot of history here.

This poor guitar from the Soviet Union has lost its bridge and all but the body is slowly dissolving into rust or goo. The vibrato unit may have also served as a kitchen appliance and thus may have been made of better metal!

Unlike 1/4″ plugs commonly used in the West, guitars from the Soviet bloc frequently used DIN plugs for amp connections. They were widely used for other audio component applications.

Other countries of note in the collection include Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria. Poland’s Defil brand produced some wild original and knock-off models. Symaeys has a lot of experience working on Polish guitars and considers himself an expert. He is now particularly fascinated by Bulgarian electrics and finds them the most challenging to investigate because virtually no information exists about these guitars. He regularly interacts with other collectors of Soviet-bloc guitars but electronic details are few and far between. He is considering spending his vacation in Bulgaria this year to hunt down and speak with people involved with these instruments’ manufacture to become more enlightened in the area. The man is on a mission.

Asked about his favorite guitar in the collection, Symaeys takes a long moment to ponder before saying, “The Dynacord Cora.” He has two – one red, one green. Talk about strange? These are one-piece neck/body constructs which are about 4″ wide at its widest part. This contains the pickup, bridge, controls and input jack. Surrounding this “rail” is a gold or silver colored tubular frame in the shape of a pointy horned double-cutaway. They are striking to behold, but apparently difficult to play.

Another favorite is his Italian Wandré “Spazial.” Wandré Pioli (profiled in VG’s “The Different Strummer,” November and December ’99) was an innovative musical instrument designer and manufacturer of quality guitars, many of which are very collectible today. The Spazial has a body made of a Bakelite-like substance and an aluminum neck. Other Italian makes are well-represented in the museum, including Eko, the accordion maker that switched focus during the guitar craze of the ’60s. It had a lot of accordion plastic in inventory, and it made for flashy/shiny guitars without the labor- and time-consuming process of multiple painting runs. They could produce appealing stripes, sparkles, or textured patterns with plastic covers and some glue. In addition, choice woods weren’t required for bodies that were going to be covered in plastics.

The Lord Bizzare collection does not contain many American amps, but one exception is this 1967 Fender Band Master with six 10″ speakers, which also serves a handy guitar stand!

The appeal of the King reaches far and wide. This Chinese solidbody from the ’60s has the word “Elvis” punched through the elevated pickguard. It’s the only identifier on the guitar.

Some of the more radical designs are from Dutch manufacturer Egmond, which sometimes used blocks of unrouted wood for guitar bodies. All-in-one units contained pickups, pickguard, controls, and input jack in a design that allowed for a surprising thin slab of wood. Some models were fitted with long trapeze-style bridges, like Egmond’s Manhattan, which were equipped with a their cord hard-wired to the guitar. This all-in-one concept was made from either molded plastic or wood painted in high gloss to look like plastic!

One of the more eyecatching mainstream pieces is a ’67 Fender Band Master with six speakers and a black control panel. There’s also the ’56 Gibson GA-90 that strays from the norm, and a ’62 Hagstrom portable. A bit smaller than a portable typewriter from its era, it opens to reveal a tube circuit that produces about four watts, complete with tremolo! It looks like a transistor radio.

As visitors make their way down the steps on the way out, they pass the Lord Bizarre workshop on the first floor, where repairs happen and guitars are propped about in various states of repair, some awaiting parts, others for Symaeys to receive some piece of technical information or simply find time to bring them back to life.

Ask Lord Bizarre about the one guitar in the world he wishes he could own, and he’ll tell you without pause, “a Jolana Big Beat from Czechoslovakia.” It’s rare, beautiful, and has dazzling electronics including a built-in radio. Not surprising, really, that he would name a guitar that is so utterly unique, but here it would hardly seem out of the ordinary!

Next time you’re in Belgium, plan to visit the Lord Bizarre museum. Contact him via lordbizarre.com to schedule a tour. And allow ample time!

Joe Bigley is a cancer researcher who often travels to Europe. During his trips he tries to visit guitar-related venues. He still has his first 1964 Silvertone acoustic and plays with friends in a garage band. He lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

This article originally appeared in VG

‘s October 2008 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar

magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Ace Frehley’s first solo album was released in 1978, when each member of Kiss simultaneously released solo albums. As it turned out, Frehley’s was the runaway favorite among fans and critics alike, and scored a hit single with a cover of Hello’s “New York Groove.”

Ace Frehley’s first solo album was released in 1978, when each member of Kiss simultaneously released solo albums. As it turned out, Frehley’s was the runaway favorite among fans and critics alike, and scored a hit single with a cover of Hello’s “New York Groove.” As for guitars, I’m a Gibson guy, but I use old Fenders, too. I have four Strats and five Teles. I played Rocklahoma last July, and the day after the show I hit some pawn shops. I found a Strat and Tele from the mid ’80s, and I got both for $1,000. The Tele sounded so good I put it on four or five songs I’d already recorded. It had that early Jimmy Page sound, and I used it on “Genghis Khan,” “Change The World,” and a couple others. I used the Strat on a couple of tracks, too. I have another cream-white Strat from the ’80s with a rosewood fingerboard and big frets. Then I found an ’83 Strat that sounds great, in a pawn shop on Santa Monica Boulevard. When you play it without an amp, it’s nearly twice as loud as my other Strats – very resonant. So I used those and a couple of others here and there.

As for guitars, I’m a Gibson guy, but I use old Fenders, too. I have four Strats and five Teles. I played Rocklahoma last July, and the day after the show I hit some pawn shops. I found a Strat and Tele from the mid ’80s, and I got both for $1,000. The Tele sounded so good I put it on four or five songs I’d already recorded. It had that early Jimmy Page sound, and I used it on “Genghis Khan,” “Change The World,” and a couple others. I used the Strat on a couple of tracks, too. I have another cream-white Strat from the ’80s with a rosewood fingerboard and big frets. Then I found an ’83 Strat that sounds great, in a pawn shop on Santa Monica Boulevard. When you play it without an amp, it’s nearly twice as loud as my other Strats – very resonant. So I used those and a couple of others here and there.

![The main hall of the museum. Some pieces that appear to be modified (such as the four-pickup model [LOWER LEFT]) are actually stock. If Lord Bizzare finds an album showing one of his guitars, he displays it near the instrument. The main hall of the museum. Some pieces that appear to be modified (such as the four-pickup model [LOWER LEFT]) are actually stock. If Lord Bizzare finds an album showing one of his guitars, he displays it near the instrument.](/wp-content/uploads/3832/02a-bizzare.jpg)