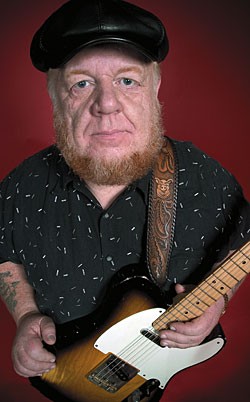

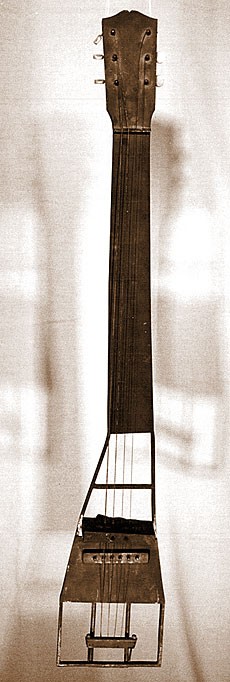

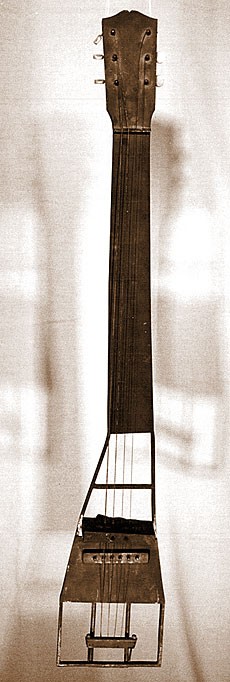

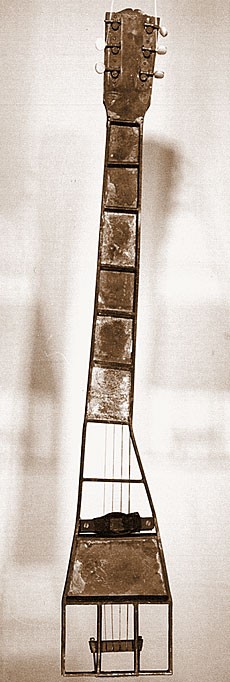

Alvino Rey and the prototype lapsteel he has kept for more than 61 years. Photos: Lynn Wheelwright

Talk about skeletons in your closet!! Believe it or not, this is the first electric guitar from the prestigious Gibson, Inc., today known as Gibson Musical Instruments.

Obviously not a production model, this instrument, used in the first stages of research and development, is too crude to even be considered a prototype of the production model. For starters, the guitar was made entirely of brass, using no wood. This was a unique approach, particularly for Gibson!

A simple ladder frame was brazed together to hold basically everything, starting with the “body” – a small piece of .050″ sheet brass mounted on top of the frame only, supporting the bridge. Also mounted to the top side of the frame only is the fingerboard, again of sheet brass. The scale length measures approximately 24 3/4″ (Gibson’s standard), although the 19 hand-sketched fret markers were only roughly laid out. The peghead shape verifies the Gibson connection and like the body and fingerboard, is made of sheet brass. A matching piece is mounted on the underside of the frame, for attachment of the tuners. These are the inexpensive strip tuners of the era, with plastic buttons.

The nut was cut from brass and brazed to the frame (is this the first brass nut?) and a rough trapeze tailpiece, with very short arms, was secured to the bottom rail of the frame. The bridge was fabricated from a slab of brass, with strings sitting on six individual brass rod saddles, nonadjustable for height. Floating free and secured only by string tension, it’s possible they were experimenting with pickup/bridge relationships by moving the bridge instead of the pickup.

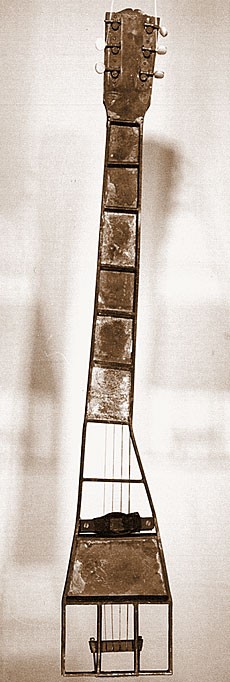

The agenda for designers Alvino Rey (Musical Advisor) and John Kutilek (Electrical Engineer for Lyon & Healy) was to come up with a patentable pickup, to avoid the possible lawsuits and licensing fees common in the early radio market. Well, this pickup was certainly different from anything on the market (although they all worked/work on the same principles of basic physics). The arrangement of the components is similar to the early Fender “boxcar” pickups of the ’40s, with the strings running between the top magnet and the coil. All magnetic pickups use a coil of wire in a magnetic field, so the arrangement of these components was of the utmost importance. A second magnet runs underneath the coil and both are approximately 4″ long of 5/8″ X 5/8″ stock (the magnetic alignment appears to be quite different from the expected reading; unfortunately, no real experts have confirmed or checked this out in person, so we’ll move on). The single coil is wound with a heavier gauge wire than normal and has two bolts running through it, acting as the bobbin for the windings. The bolts are secured to the bottom magnet and three nuts on each act as spacers to hold the coil in place. The bolts also project through the coil and each has a roughly-shaped piece of metal that acts as a three-strings-in-one polepiece.

Like the Electro/Rickenbacker, the top of the pickup acted as a handrest. The pickup was hardwired to a cable, so there is no output jack or controls. Considering Mr. Rey’s early employment of both volume and tone controls for sound effects, this seems odd. Unfortunately, the instrument “took a dive” a few years ago, so the electronics are not currently functioning, although it’s possible the guitar could be restored. The cable (with four-prong PA connector) has broken off and the pickup came apart from the body, although it has been reattached. The original asymmetrical shape of the guitar has been somewhat exaggerated by the tension of the four remaining original strings, which today do not quite line up with the fingerboard.

Other than these “minor details,” the guitar would probably work as well as it ever was supposed to. There never was a case, and the requisite matching amp of a production model is also not available, as the research and development was done through the L & H factory’s PA system.

So, as a “collector’s item” (as antique/flea market dealers love to say) it would appear to be incomplete and in only VG– condition. To anyone with an appreciation for the broad scope of Gibson’s history, it should be obvious that this is a most important disc-overy…and that its existence and documentation today is a miracle. Otherwise, who would believe it?

Alvino plans to be present to “unveil” the guitar at the Gibson booth at the Winter NAMM Show (Anaheim Convention Center, January 16-18, 1997), coinciding with it being featured in their new catalog. It will also be on display at the Vintage Guitar magazine booth the weekend of January 17-19 the California VAMM Guitar Show (Orange County Fairgrounds).

gen•e•sis (jen’ sis) n. [Gr] the origin or coming into being of something

When Gibson released their first production electric guitar and amplifier in late 1935, they were already well-established as a progressive acoustic instrument company, known for both innovative design and high standards of craftsmanship. The electric instruments of the 60-plus years since have maintained the design and craftsmanship tradition while playing a continually influential role in the acceptance of the electric guitar.

Popular with the general public since their inception, a vast majority of the models are still considered seriously for professional use. The number of Gibson instruments from the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s and ’60s that today reside in the elite $2,500-and-up section of the vintage electric guitar market is testimony to their timelessness, usefulness and desirability. Their near total domination of the “five figures and up” category speaks volumes.

Needless to say, much has been written about the importance of Gibson’s electrics, yet little has been told about the mid-1935 experiments by Alvino Rey, John Kutilek and later, Walter Fuller, that led to their introduction. All three of these key figures are alive today and were contacted for their recollections on the subject. Amazingly, the research and development guitar from the earliest experiments has also survived – a silent corpse of trial and error today, but the inspiration for all those wonderful Gibson electrics that followed. The 27-year-old Alvino Rey had the wherewithal in 1935 to hold on to Gibson’s first electric guitar and has kept it relatively intact for 61 years. To help put the design of the instrument into perspective, here’s a look at the company’s involvement with electrics from Lloyd Loar to the ES-150.

On more than one occasion prior to 1935, the folks at Gibson dabbled with the idea of electrifying the guitar, using a pickup and an amplifier. However, the contemporary state of electronic technology did not allow them much room for success. As far back as 1923-’24, Gibson employees Lloyd Loar, Lewis Williams and Clifford Buttleman were investigating the possibilities of applying recent advances in radio technology to stringed instruments. While some experimenting appears to have been done, there is little evidence a working model was ever actually built.

Front and rear view of the brass-framed lapsteel prototype. Note how it has “deformed” over time.

They encountered several problems. In the early ’20s, operating an audio amplifier required the use of inefficient B+ batteries (also separate A, and in some cases, C batteries), making the reproduction of music (broadcast radio and early electrified Victrolas) somewhat impractical, as well as expensive. The single-ended triode amplifiers were very low-powered and the one and two-stage circuits lacked enough gain to bring weak signals to full output. While local radio stations supplied a strong enough signal to allow for the use of a large speaker horn (similar in shape to the acoustic model of the Victrolas), headphones were often needed to hear distant stations. Cone speakers were still in the development stage. Only the largest (and very expensive) public address systems could amplify a signal to a level louder than the original, whether voice or music, and the frequency range of the giant horns lacked seriously at both ends of the spectrum. Even with the early development of talking pictures, electricity was used to transmit and audibly reproduce real world sounds, not make them louder. This suggests the extent, results and importance of the Lloyd Loar-era Gibson “experiments” have been exaggerated over the years (as does research into Loar’s vocations following his departure – he did not immediately jump into electric guitar building, as has been implied in the past). It would be a number of years before Gibson was again involved with developing an electric instrument.

With the release of the rectifier tube in late 1927, amplifiers for audio reproduction became practical, no longer relying on batteries. Circuit and component improvements, such as push/pull outputs employing screen grid tubes, led to the amplifying of music for reaching more people than was possible with acoustic instruments. When the 1920s met the 1930s, Gibson electrified a small number of acoustic archtops, e.g. J. Bellson’s famous L-4 (with amplifier) photo and an extant L-5 model owned by collector Scott Chinery.

Apparently, all of these were designed in the style of late-’20s Stromberg-Voisinet and Vega production models, using a pickup mounted to the underside of the top (leftover pickups from this time may very well have been mistakenly attributed to Loar’s tenure). While far from the volume of a modern electric guitar/amplifier set, stringed instruments were beginning to compete with the louder brass and woodwinds, as well as the recently-released resonator instruments by National and Dobro.

The designs of all the early pickups were based on the reproduction of vibrations being acoustically transferred from the strings, through the bridge and into the body. The idea of an electric instrument with a string-driven magnetic pickup, as opposed to earlier electrified instruments, would become the industry standard by the mid-’30s (except for ViviTone), with the George Beauchamp designed Electro Steel and Spanish models hitting the market in October, 1932.

Dobro followed with a full-page ad for the All-Electric in April, 1933, using an under-the-strings magnetic pickup design patented by Dobro and reportedly purchased for $600 from an Arthur Stimpson, listed as the designer (new info regarding Stimpson and Paul Tutmarc’s roles in the regionally released, early-’30s Audiovox electric instruments and amplifiers should hit the pages of this magazine soon). Vega offered the “Vegaphone Amplifier for all stringed instruments” (undoubtedly including some kind of pickup) in July, 1933, with the statement “Amplification is not new to Vega.” The Volu-Tone amplifier and pickup set of September, 1933, featured a pickup of the string-driven magnetic-type that mounted to the top of any steel-stringed instrument.

The idea of adding a pickup (and amplifier) to an existing instrument actually made a lot of sense, especially considering the lack of quality common to the production electrics before 1936 (as in Harmony and Regal bodies with Rickenbacker and National/Dobro electronics). All the electric instruments were sold with an amplifier as part of a set, and priced as such.

By mid 1935, it was obvious the electric guitar market was growing quickly, with favorable response from the general public. The Electro line had additionally taken on the Rickenbacker name and was being distributed and promoted on a national level by the Progressive Musical Instrument Corp. of New York, and the Coast Wholesale Music Co. of San Francisco. The National and Dobro companies had moved in together at 6920 McKinley Avenue, in Los Angeles, and were featured in large ads promoting aluminum steels and wooden Spanish models. A number of highly-visible guitarists were going electric, so when Gibson’s main archtop competitor, Epiphone, entered the electric guitar field, the folks in Kalamazoo seemingly had no choice but to join the race (for details on the Gibson/Epiphone rivalry see Jim Fisch and L.B. Fred’s new book Epiphone, The House of Stathopoulo).

Looking at the mid-1935 Gibson R & D guitar gives the impression the company was starting from scratch, which is not entirely the case. Enter the highest profile electric guitarist of the time, Alvino Rey, featured daily over the airwaves nationally with Horace Heidt’s Brigadiers.

Rey had purchased an Electro steel guitar in 1932, and quickly integrated the new sound into his radio act. When the band came to Chicago from San Francisco in May of 1935, Gibson’s General Manager, Guy Hart, quickly approached Rey (an endorser of the L-5 since 1929) for a new project, seeking his experience, his ear and his Electro steel guitar and amp (Andre Duchossoir’s revised edition of Gibson Electrics stated the year was 1934, based on statements from Gibson employees; however, the Rey’s family scrapbook – as well as Gibson catalogs – definitely place Rey in San Francisco for all of 1934 and not in Chicago until May of 1935).

Lacking the necessary test equipment to develop an electric guitar and amplifier set, Gibson subcontracted the long-established musical merchandise giant Lyon & Healy, Chicago, to perform the R & D (Electro/Rickenbacker, National, Dobro, Vega and Epiphone also subcontracted the building of their amplifiers). Working at the L & H factory with their top electrical engineer, John Kutilek, Rey was given the opportunity to try some of the designs he had been accumulating during his years with the Electro set.

As you will see in later features on Mr. Rey and his personally-designed instruments, the man created whatever he needed to make an instrument accommodate his musical id. Handwritten notes and diagrams on hotel stationary from 1935 have survived, suggesting a one-man think tank, e.g. placing two separate coils in series (humbucking), having the tuner shafts placed so that the strings pulled straight over the nut, having the tuners at the bottom end of the guitar acting as individual tailpieces (Steinberger style), adding variable capacitance to the tone circuit (Varitone) and jumping from the speaker output of one amp into the input of a second.

The lapsteel’s pickup, photographed from the bridge side.

Less practical (but equally fascinating to ponder) were the ideas of piano hammers under the strings, running the strings in series with the pickup coil, and last but not least, connecting the bar (steel) electrically to the circuit! Unfortunately, this brainstorming did not produce a truly-unique instrument in the time afforded, and the guitar-half of the project was sent to Kalamazoo after approximately three months.

It is important to remember that Gibson was an industry leader, and that simply releasing a clone of instruments already on the market was not part of its original plan. Avoiding a patent infringement on the pickup design was most important, and much of the time at L & H was devoted to that end. Different materials for the bodies were also tried, with a number of other “prototypes” constructed. But Rey’s Electro set, the experiment’s laboratory control, could not be topped before the project moved to the Gibson factory.

Time had become a factor as the company basically started over on the instrument with Walter Fuller heading the R & D (Kutilek/L & H was still responsible for the production model E-150 amplifier). Electro/Rickenbackers had aluminum bodies, Dobros had aluminum bodies, Nationals had aluminum bodies, so the “new” Gibsons, released only a few months later, had aluminum bodies (Vega and Supro aluminum steels, advertised in 1936, were possibly also on the market in 1935).

Electro/Rickenbacker’s horseshoe pickup was more identifiable than Dobro and National’s, so Gibson reworked the magnets-under-the-coil style, using the ends of two specially-ordered Alnico bar magnets at opposite ends of the coil to develop a stronger field than was available from any single magnet. This is the pickup referred to today as the “Charlie Christian model.”

In only a few short months, the company was able to release a respectable steel guitar, placing Gibson in a growing market that would move approximately 2,000 sets in 1935 and twice that in 1936 (according to NAMM figures published at the end of 1936). The E-150 set included the tweed Lyon & Healy made amp, a matching tweed case for the instrument and the aluminum steel guitar which featured Alvino Rey’s tone roll-off control, the first production electric instrument with this oft taken-for-granted circuit. Rey, still involved with Gibson, received one of the first examples of this model for himself, as well as a doubleneck, made up of two aluminum instruments mounted into rubber and sunk into a Gibson-made curly maple body (more on these in future articles).

According to factory records, 98 aluminum steels were assembled, including seven that went to the “Singing Guitar Orchestra” of Kalamazoo. These were still being shipped as late as March 1936.

Epiphone began running ads for its wooden-body Electar steel guitars (also an electric Spanish, both with very Electro/Rickenbacker-like pickups) in November of 1935, and around the start of 1936, Gibson followed them in their choice of construction material. Negative dealer response to the simple aluminum body and difficulties in casting the bodies are other often-cited possibilities for the switch to wood.

While the Epiphone was rather plain, Gibson’s new EH-150 steel was a superbly-crafted miniature guitar, featuring bound top, neck and pickup and inlaid fingerboards and headstocks.

Was this guitar influential? In 1936, Rickenbacker, Dobro, National, Vega, Supro and Supertone, by Sears, all had aluminum bodies. By the end of 1937, they had all switched to wood, except Rickenbacker, which was actively pursuing Bakelite.

There was no mention of any electric instruments in Gibson’s “New Models – Gibson Guitars” flyer dated January 1, 1936, which introduced the “Advanced Models,” “Improved Models,” and “New Models” of archtops, as well as all the flat-tops, the Roy Smeck Stage Deluxe and Radio Grande Hawaiian Guitars, and the new tweed cases (“Alvino Rey – Horace Heidt’s Brigadiers – Chicago” was pictured with a Super 400). A Gibson ad from May 1936 listed all styles of instruments made by the company, again with no mention of anything electric, even though the first electric Spanish guitars were about to be shipped. Finally, in October, 1936, an ad was run for the new wood-bodied EH-150 set with no mention of any other electrics.

It seems the company was playing it safe and getting back endorser and dealer response before launching a serious promotional campaign. Gibson’s Catalog X, of December, 1936, was the first to feature electric instruments and Alvino and Horace were pictured with the wood-bodied EH-150. The EH designation distinguished the “New Model – Electric Hawaiian Guitars” (EH-150 and EH-100) from the “New ES-150 Model Electric Spanish Guitar” officially released late in 1936. The importance of the ES-150, with its pickup mounted near the neck in defiance to Rickenbacker, Dobro, National, Vega and Epiphone Spanish models, should be well-known to readers of this magazine. The rest, as they say, is history.

This article originally appeared in VG

‘s Feb. ’97 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar

magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.