1966 Vox Guitar-organ and ’66 Phantom XII. The Guitar-organ was a Dick Denney creation that combined the mechanical elements of a Phantom guitar with the oscillators of a Continental electric keyboard. Photo: VG Archive.

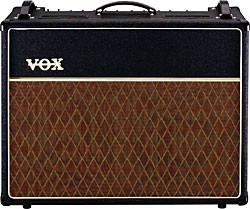

In an industry hardwired to perpetually churn out a “next big thing,” any design that remains the kid to beat for going on 50 years deserves it’s own chapter in the annals of tone. And Vox has certainly got it.

Mention that oft-wielded phrase “class A” and Vox’s AC30 and AC15 amplifiers come to mind first every time… followed by the plethora of significant models from dozens of other makers, boutique and production alike, who owe an enormous debt to Dick Denney’s seminal EL84-based creations. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, Vox amplifiers must feel flattered to pieces here in their sixth decade.

Vox founder Tom Jennings’ Jennings Organ Company had been selling portable organs and related gear since 1951, but upon establishing Jennings Musical Instruments (JMI) in 1957 in order to cash in on a booming guitar craze, he set engineer Dick Denney to the task of designing an amplifier aimed at doing just that. The AC15 was released as the new company’s flagship model, to almost immediate acceptance from British guitarists on the skiffle, jazz, dance band and – most crucially – rock and roll scenes. Musicians of the day were gagging for gigworthy, home-grown products amidst a dry period for quality that was exacerbated by a ban on the importation of U.S.-made goods that lasted from 1951 to ’59. The Shadows, pop crooner Cliff Richard’s backing band, became almost immediate endorsees and stuck with the AC15 until success demanded a bigger amplifier (Vox’s impetus for releasing the AC30), and virtually any British guitarist of note of the late 1950s and early ’60s will have played through an AC15 at one time or another.

The AC15 (its name an abbreviation of “Amplifier Combined with Speaker, 15 watts”) is frequently billed as the first tube amp designed specifically for the electric guitar. There is an element of truth to that, although the claim is also a bit misleading. To clarify, while Fender, Gibson, Valco, and other manufacturers were producing amps from adaptations of circuits found in the applications handbooks that tube manufacturers such as RCA, G.E., and Mullard routinely provided with their products – which laid the groundwork for hi-fi amps, P.A. amps, accordion amps, whatever – Denney crafted the AC15’s circuit from the ground up with the intention of flattering the natural tones of the electric guitar. As excellent and successful as Fender’s Deluxe and Tremolux amps of the late ’50s were, few other manufacturers gave much consideration to the designs of their sub-20-watt models. Denney was different. Instead of just cobbling together a medium-powered gramophone amp with a 1/4″ input and a built-in speaker, he voiced every element of the AC15’s circuit to accentuate the guitar’s full lows, forward mids, and shimmering highs.

One of his more extraordinary steps was to employ the very efficient and lush-sounding Mullard phase inverter topology to drive the output stage, which has since become known as the “long-tailed pair.” This is a more complex stage than other manufacturers of the time were willing to take the trouble to put into a relatively small amp. Fender had only just started using it in its big Bassman, and would only put it in the high-powered Twin a year later. (For a more detailed examination of the AC15 see the “Amp-O-Rama” column, March ’07.) Although the AC15 is viewed as the template for many two-EL84-based amps that would follow, it is quite different from most. The EF86 pentode preamp tube in the Normal (a.k.a. “Brilliant”) channel, EZ81 rectifier tube, and versatile “Vibravox” tremolo/vibrato effect make it stand apart from anything available at that time or for the next 45 years, in the U.S. in particular. In recent years, TopHat, Gabriel Sound Garage, 65 Amps, and a handful of custom-order makers have launched more meticulous recreations of the AC15, and these high-end homages give a good indication of the AC15’s desirability today. The demand for this format has also recently led Vox to reissue its own hand-wired AC15.

1965 Vox Berkeley Super Reverb. Photo: VG Archive. Amp courtesy Bob Tekippe.

A year after the AC15’s arrival, Vox introduced the little AC4 practice amp, and the “student” sized AC10, which had features similar to the AC15 but produced only about 10 watts into two 10″ Goodmans Axiom speakers. Meanwhile, rock and roll’s appeal continued to grow, and a more powerful amp was also needed, so Denney and Jennings designed a big brother. In creating the amp that would ultimately fit the bill, they simply doubled the two-EL84 output stage of the AC15, added a GZ34 rectifier and larger transformers to provide adequate power and output, and the AC30/4 was born (the 4 denoting its four inputs, two each for the Normal and Vib-Trem channels). The increased power made it a more versatile and more rocking amp all-round, which is actually capable of putting out more than 36 watts in good condition, and it quickly became the flagship of the Vox line. Both the AC15 and the AC30 originally carried the more unusual EF86 preamp tube in their Normal channels, which most likely fell out of favor with guitar amp makers because it can become extremely microphonic when exposed to mechanical vibrations over an extended period of time (which pretty much defines a roaring, 36-watt 2×12″ combo amp). They also originally had Vox’s unique Cut control, which can be used to reduce high frequencies at the output stage without severely dulling the overall tone of the amp – a very useful feature in any amp based on EL84s, which can be prone to aggravating high-frequency artifacts if not tamed adequately. In 1960, Vox changed the AC30’s Normal channel to employ the less troublesome ECC83 (a.k.a. 12AX7) in place of the EF86, although the AC15 retained the pentode until its demise at the end of the ’60s.

Throughout the early ’60s, the AC30 and AC15 shared another ingredient that deserves a slice of the credit for helping to create “the Vox sound.” Vox had started off using Goodmans Axiom speakers and standard Celestion G12s in the late 1950s, but Dick Denney was never entirely happy with either. They commissioned a more guitar-oriented driver from Celestion that was finished in a striking blue enamel (later in silver, too) and re-labeled by Vox: the legendary alnico speaker that became known as the “Vox Blue.” This unit has the reputation of being one of the sweetest, most flattering speakers ever used for guitar, and it helped push the AC15 and AC30 over the top on tonal terms.

In the eyes – and ears – of many players, the archetypal AC30 wasn’t born until a couple years after the model’s introduction, when Denney devised the Top Boost tone circuit. This was essentially an adaptation of the cathode-follower tone stack as famously used on Fender’s tweed Bassman, minus the Middle control and tweaked for the AC30, and was first available in 1961 as a back-to-factory retrofit modification, which included adding the extra preamp tube required and mounting the Top Boost’s Treble and Bass controls on a plate bolted to the amp’s back panel. In ’64, the AC30 Top Boost model came direct from the Vox factory as an upgrade option, with the extra knobs mounted right on the main control panel and six inputs for the Vib-Trem, Normal and Brilliant channels. Wherever you find it, this Top Boost EQ stage adds the extra sparkle and high-end content that bands of the day were looking for to help cut through a mix, and is a big part of that classic Vox shimmer and chime. Most early Vox endorsees had moved over to the AC30, Hank Marvin and The Shadows being most notable among them – a fact which might have inspired a young beat group from Liverpool to acquire a pair of fawn AC30s in 1962. Very soon, The Beatles would prove Vox’s greatest international ambassadors, helping to make the brand a sensation in the U.S. as well as the U.K.

1963 Vox AC-2. Photo: VG Archive. Amp courtesy Bruce Barnes.

The Fab Four’s runaway success soon demanded even bigger amplifiers, and over the next couple of years virtually every significant advancement in Vox’s firepower was made thanks to a specific request from The Beatles. In ’63, Denney designed the prototypes for the 50-watt AC50 specifically to suit John Lennon and George Harrison’s need for more volume; the bass version of the AC100 was conceived immediately on the heels of these to help Paul McCartney’s bass be heard over the thousands of screaming fans that were turning out to see the band. These amps were offered to the general public in ’64, by which time The Beatles needed even bigger amps, and the AC100 guitar head and cab were developed again specifically to suit Lennon and Harrison’s needs – and just in time for the band’s second U.S. tour, begun in August of ’64. The AC50 and AC100 used two and four EL34 output tubes respectively to produce a nominal 50 and 100 watts, although noted Vox historian and amp tech Dave Petersen (co-author of The Vox Story with Dick Denney) has said an AC50 can put out close to 70 watts in a good tailwind. These amps were designed specifically to produce as much clean, punchy power as was practical, and consequently these aren’t great crunch-rock or lead amps like some other notable tube designs of the day. Consequently, while the AC50 and AC100 are somewhat collectible – thanks in large part to their Beatle associations – they have never achieved the desirability of the AC30 or AC15, or perhaps even the AC10.

Ironically, the JMI company’s success in the early to mid 1960s, kickstarted in large part by Beatlemania, also triggered the company’s downfall. In a rather frantic effort to acquire the funds necessary to expand and capitalize on the rock and roll boom and Vox’s newfound popularity in particular, Jennings sought out investors, and eventually sold a major portion of the company to the Royston Group toward the end of ’64. A deal was configured to license the Vox name to the Thomas Organ Company, of California, in order to (so Jennings thought) distribute U.K.-made Vox amps throughout the U.S., which Vox intended to manufacture in greater numbers than ever thanks to the fresh injection of cash. What actually happened, however, was that after importing a few genuine tube-based Vox amps, Thomas Organ began to manufacture its own far-inferior solidstate amps in California, and to sell these Vox-branded versions to American guitarists eager to get their hands on Beatles-associated gear. In hindsight it sounds like an incredible con job, but it was all apparently legal according to the paperwork that Vox, Thomas Organ and Royston inked at the time. While Vox continued to manufacture some of the greatest tone machines of all time back in England, players in the U.S. were being sold these repairman’s nightmares from Thomas Organ with Brit-associated names like Westminster, Royal Guardsman, and Cambridge, and were scratching their heads when harsh and totally non-Beatlesy sounds woofed out of them. To add insult to injury, these amps were frequently sold off the back of magazine ads that showed The Beatles playing U.K.-made Vox tube amps. (It’s worth noting that Denney designed a quite decent-sounding and more reliable range of solidstate amps in 1966, which included the 35-watt Conqueror and 50-watt Defiant, both of which are rumored to have been used by The Beatles for the recording of Sgt. Pepper.)

Dick Denney (left) and Tom Jennings in the 1960s with a Vox teardrop guitar. Photo courtesy of Korg.

Having lost virtually all control of the company, Tom Jennings departed Vox in ’67, and designer Dick Denney went with him. Together, Denney and Jennings established the short-lived Jennings Electronic Industries (JEI) in 1968 in Vox’s Dartford premises, where they manufactured some effects pedals, an early synthesizer, and a tube guitar combo called the AC40 which, yep, had three channels including Vib-Trem, Top Boost tone controls, four EL84 output tubes, and two Celestion alnico G12 speakers. JEI dissolved in 1973.

Vox has always been best known for amplifiers, but a few other instruments deserve a cursory mention at least. JMI first jumped into the electric guitar game in 1961 with the Stroller, Clubman, and Apache models, manufactured by an English furniture maker. In ’62 JMI’s Dartford factory ramped up production for its own model, the Phantom, with three single-coil pickups, a “Hank Marvin” vibrato, a bolt-on neck made by Italian guitar manufacturer Eko, and a distinctive, trapezoidal body conceived by The Design Centre in London. The Phantoms were joined by the more oblong and rounded Mark VI and Mark XII in 1964, the former perhaps most famously seen in prototype form in the hands of Rolling Stone Brian Jones. Full production was moved to Eko’s Italian factory in ’66, and the line was discontinued in ’69. More budget-minded Vox guitars from offshore manufacturers occasionally surfaced over the years, but the brand wouldn’t be seen on a quality electric guitar for more than two decades. The Phantom name is now owned by another manufacturer; American-made versions of the Vox Mark Series guitars were reintroduced in the late ’90s to an enthusiastic reception in some quarters, but the range has once again been discontinued.

Another of Vox’s “sidelines” – one that might have been expected to be even more of a flash in the pan than the odd-shaped guitars – has proven to be an enduring icon of tone. Like all gear manufacturers of the day, JMI saw the wisdom of offering a range of accessories alongside its popular amplifiers. From the mid ’60s the Vox range included a Volume Pedal, outboard Vibravox vib-trem, Echo DeLuxe and Vox Reverb units, a Bass Booster, Treble Booster, and Tone-Bender Fuzz and more, many of which were manufactured out of house. The Treble Booster and Tone-Bender retain some iconic status today. But looming above them all is the Vox Wah-Wah, the wah of choice of no less than Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton.

As much as the deal with Royston and Thomas Organ helped initiate the downfall of JMI, it did bring about a brief sharing of technologies that enabled Vox to ingest the design for one of rock’s greatest effects pedals.

As the rather sketchy history has it, Thomas Organ engineer Brad Plunkett invented the wah circa ’65, and it first hit the market as The Clyde McCoy Wah-Wah Pedal, named for its imitation of the then-famous trumpeter’s mute technique. From there, the pedal evolved down separate but related paths into both the Vox Wah-Wah and the Thomas Organ Cry Baby, with various changes in production location and circuit design along the way. Dick Denney adapted the schematic to make the most of local components for a brief manufacturing run in JMI’s plant in Dartford, Kent, then farmed out production to Jen Elettronica in Pescara, Italy, where the Vox transistorized effects were already being made (you begin to wonder if the men from Dartford just wanted some time in the Italian sunshine now and then). Some early Clyde McCoys were made in California, then Thomas Organ also moved production to Jen. In ’68, the most famous incarnation of the Cry Baby was offered for sale in the U.S., but Vox-branded Cry Baby pedals were also sold in the U.K. around the same time as a product distinct from the Vox Wah-Wah. Early versions of all of them were made with the red Fasel inductor, one of the components that contributes to the effects’ legendary sound. Despite their common root, the Vox and Cry Baby wahs have distinctive characteristics that have led different guitarists toward one or the other; the Vox is singing and flighty, the Cry Baby somewhat sweeter and more fluid, with a shorter rocker travel. Both have attained Holy Grail status among collectors and players.

Vox Phantom VI, Guitar-organ (with its power supply perched atop a ’64 AC30 head), and a ’64 AC30 combo. (front) a Thomas-Vox Wah Wah. Photo: VG Archive.

The rocky path that the Jennings Musical Instrument company stumbled through led to a name change to Vox Sound Ltd. in 1970. Although the convoluted licensing deal with Thomas Organ clearly played a big part in JMI’s decline, other contributing factors included a misguided effort to push U.K. solidstate amps over the clearly superior sounding tube models from the mid ’60s onward, and the increasing popularity of the heavier rock styles of Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Pete Townshend, and the like, who were doing their things through 100-watt Marshall and HiWatt stacks.

In 1970, Vox Sound Ltd revised the all-tube AC30 with added reverb and electronics manufactured on a printed circuit board (PCB) rather than the previously hand-wired tag strips of the JMI amps.The AC15, on the other hand, vanished entirely. In ’72, Vox changed hands yet again when bought up by CBS-Arbiter, for whom Tom Jennings worked as a consultant from 1973 until his death in ’78 (Dick Denney passed away in 2001). Manufacture of the AC30 was taken up at the company’s Shoeburyness factory, and the result was a product vastly inferior to anything that had gone before. The model continued to have its ups and downs throughout the ’70s and into the ’80s, at the hands of new owners Rose Morris from 1979, who continued to build AC30s to much the same Vox Sound/Arbiter formula. They remained mostly sad days for Vox lovers, and JMI AC30s from the ’60s became ever-more appreciated. The model finally saw some respect again in 1990, when Rose Morris upgraded the specs. First a Limited Edition run of 1,000 numbered “old and improved” combos was offered, then – the experiment proving a success – a standard production AC30 Vintage combo and piggyback rig in 1991. This incarnation was shortlived, but further changes continued for the better.

A recession-hit Rose Morris sold the Vox name to a new management team under the Korg umbrella in late ’92, and by ’93 further improvements were made, most visibly seen in the return of the GZ34 rectifier and the Alnico Blue speakers, newly reissued by Celestion. In ’96, Korg brought the Vox AC15 back to the market after some 26 years in the wilderness. The revised AC15TBRX model (TB=Top Boost, R=Reverb, X=Celestion Alnico Blues speaker) was an updated design more than a reissue, with master volume, reverb, and a 5Y3GT rectifier rather than an EZ81, but it nevertheless became a popular club and recording amp.

The AC30TBX made under Korg’s supervision is widely considered the best standard-production AC30 since the JMI years, and the Vox brand in general has fared extremely well through the ’90s and into the new millennium with the company’s muscle behind it. Toward the end of 2004, however, the TBX amps were discontinued and the company branched the model in two directions; for players on a tighter budget, the China-made AC30CC (Custom Classic) gave a good tube-based rendition of the class A sound with added modern features, while the limited-run Handwired AC30, designed for Vox in 2002 by boutique amp maker Tony Bruno, brought the closest available thing to the original specs and sound. The AC15CC1 (and CC1X with Alnico Blue) followed shortly after, along with – just this year – the hotly anticipated, hand-wired Heritage Series AC15H1TV, complete with EF86-based Normal channel and EZ81 rectifier tube.

Vox’s expansion into Chinese manufacturing sparked controversy among some longtime fans. But Steve Grindrod, Managing Director of Vox R&D, is quick to point out that the company went to great lengths to ensure the quality of production in Asia. When it became clear that full U.K. production was no longer viable, he undertook a “world tour” to find the best offshore manufacturing option, and a Chinese factory got the nod.

“These guys own and build various world beating hi-fi and sound reinforcement brands,” said Grindrod. “Another important factor was that some really great English audio engineering guys are based there, one of whom is one of the world’s greatest speaker designers. These things help!” Regarding the bad rap that Chinese industry often receives these days, Grindrod adds, “To put the record straight, working conditions and personnel development were very important, as well. China has its reputation, but it also has a very good and advanced side. We could have gone elsewhere and made a cheaper product, but it would not have been the same and I certainly would not have felt good about it… Also, every design step has been with the intention of retaining the classic Vox ideology and tone. Again for the record, we do all the design and manufacturing control work here in Vox R&D UK Ltd.”

The Chinese-made tube range has also expanded this year to include the larger Classic Plus amps, the AC50CPH head, AC100CPH head, and AC50CP2 combo. Alongside these and a comprehensive range of smaller solidstate practice amps and effects and a well-regarded reissue of the classic Vox Wah, the groundbreaking Valvetronix digital range, launched in 2001, caters to some guitarists’ desires to have a multiplicity of sounds available from a single amplifier. The flagship AD120VTX uses Korg’s REMS digital emulation technology in a stereo preamp designed to replicate the sounds of vintage Vox tube amps alongside many classics from other makers, and employs a single 12AX7 dual-triode in front of the output stage in an effort to give “tube-like feel” to the solidstate stereo power amps. Although the debate between the digital and all-tube camps continues to rage, the Valvetronix range – which includes a diverse number of heads and combos – has been extremely well received within the emulation field, as has the ToneLab series, which houses the same technology in a range of floor-controller-like units.

Having hung on through stormy seas for more than two decades, the Vox brand and its flagship, the AC30, appear to have achieved the stability that was, ironically, so illusive to Tom Jennings throughout the years that the most desired Vox products were being manufactured. Between the financial backing of the mighty Korg conglomerate and past and present associations with artists such as The Beatles, Brian May of Queen, Lenny Kravitz, REM’s Peter Buck, both Tom Petty and Heartbreakers lead guitarist Mike Campbell, Dave Grohl of Foo Fighters, and a shedload of contemporary artists, Vox is looking not just strong but positively musclebound heading into its second 50 years.

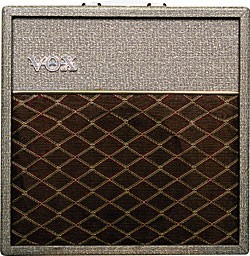

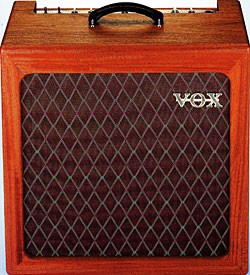

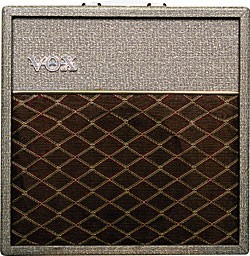

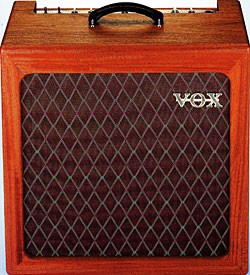

Vintage touches on the AC15H1TVL Limited Edition include a pre-1960 logo placement, vintage-inspired cream vinyl covering. Two hundred will be produced with oiled mahogany cabinets.

Woody Wonder

Vox’s limited-edition AC15H1TVL

To commemorate its 50th anniversary, Vox has issued its Heritage Collection of handwired amplifiers. The first two models, the AC15H1TV and the limited-edition AC15H1TVL, pay tribute to the AC15.

The amp uses an EF86 Pentode valve circuit (developed by Vox in 1960) in the preamp channel, combined with the 1963 Top Boost channel, coupled with Vox’s modern tone-shaping control enhancements.

Channel 1 uses the EF86 preamp and includes two inputs wired traditionally, which gives one of those inputs a 6dB gain boost. Vox says Position 1 on the two-position Bass Shift switch is voiced to the original vintage-correct bass response, while Position 2 tightens bass response and reduces muddiness during high-volume use. The three-position Brilliance switch flattens response when off, while position 1 is voiced like an early AC30 “Treble” amp and position 2 is the original Brilliance circuit, which acts as a bass cut. The EF86 Mode switch reconfigures the EF86 tube from Pentode to Triode; Triode gives lower gain and more headroom, while Pentode is the original high-gain tone with less headroom.

Through Channel 1 in Pentode mode with the Bass shift set to 1, the Cut control set to full, and the Brilliance channel off, a 1972 Fender Stratocaster sounds tight and full, with abundant, round low-end and nice sparkle. Overall, the AC15H1TVL is always very responsive. Taking the Volume up produces markedly more gain while the tone remains firm. And even with the Volume dimed, it stays tight – awash in smooth, pleasing class A gain. In Triode, it produces less gain and volume, but retains all of its tone.

With a humbucker-loaded solidbody, Channel 1 sounds wonderfully fat. Even at high gain settings it offers smooth-but-firm gain with nice sustain. The Brilliance and Bass Shift switches dial in varying degrees of clarity, while the Cut control dials in “sweet spots” galore.

With the Strat and the Brilliance switch in position 1, the AC15H1TV offers more sparkle with tighter low-end; still very smooth and sweet, with great touch response. Brilliance 2 adds sparkle with an upper-mid boost and even less low-end. Channel 2 uses the Top Boost preamp and two inputs, with a 6dB difference in gain. The highly interactive Treble and Bass controls are taken from the 1963 Top Boost circuit, and very minor adjustments of these can yield dramatic changes in tone color. The Top Cut control, per tradition, cuts high from either channel as it is turned up.

Through Channel 2 set to clean, a Strat sounds very nice, with tight lows and responsive highs. The Tone control reacts nicely. Pushing the Volume brings more upper-mid harmonics, while pushing the Gain hard for a more compressed British-style distortion; still very smooth and with brilliant highs. The Ibanez sounded big and fat, with great class A sparkle and touch-sensitivity. The ramped-up gain retains a nice top-end sparkle, with rich harmonics.

The AC15H1TVL is the official limited-edition Anniversary model, with an oiled hardwood cabinet. Only 200 will be built. The AC15H1TV, with its a Baltic birch cabinet and cream anniversary vinyl covering, will be a permanent part of the Heritage series. – Bob Tekippe

This article originally appeared in VG

‘s November 2007 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar

magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.