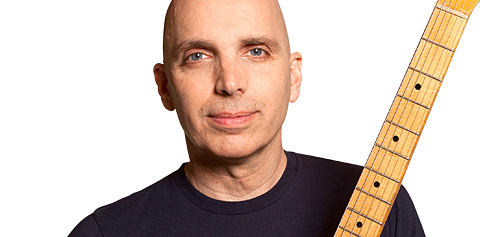

When he emerged in the late ’80s, rock guitarist Joe Satriani stood apart from the hair-band crowd for several reasons. Like most of his contemporaries, his style was a mix of classical and classic rock, heavily influenced by Jimi Hendrix and Jimmy Page. Also like his peers, he was fully capable of the shred-tastic scalar runs and quick-fingered tricks that were the flavor of the day.

But the similarities mostly ended there, because while most ’80s rock players were working solos to dress up regular ol’ songs, Satch’s music was almost entirely instrumental. His style focused on melodic runs like those heard on “Surfin’ With the Alien,” his 1988 song that set him apart from the crowd in that 1) it was an instrumental and 2) it was a hit!

While you’ll rarely see him onstage playing anything other than his signature-model Ibanez, in the studio, he makes heavy use of a bevy of cool vintage instruments.

Most recently, Satriani joined Sammy Hagar, Michael Anthony, and Chad Smith in Chickenfoot, a straight-up rock-and-roll collaboration that, as we’ll learn, first happened in Vegas… but didn’t stay in Vegas! We caught up with him as Chickenfoot’s second album, Chickenfoot III, was set for release.

You can receive more great articles like this in our twice-monthly e-mail newsletter, Vintage Guitar Overdrive, FREE from your friends at Vintage Guitar magazine. VG Overdrive also keeps you up-to-date on VG’s exclusive product giveaways! CLICK HERE to receive the FREE Vintage Guitar Overdrive.

What are some of your earliest musical memories?

I remember a moment… My family was in upstate Vermont, on summer vacation. I couldn’t have been more than six or seven. We were dropping off my older twin sisters at a dance for teenagers – they’re eight years older – and they let me step in the door for a minute. The band was playing “Satisfaction” by the Rolling Stones, and the feeling I got watching the sax player doing Keith’s riff was the greatest I’d had up to that moment. The excitement of it – the sound of the band. I remember thinking from that moment, “That’s what I want to do. I want to make music.” Even at that young age, I knew it was the greatest thing ever. I was there for, literally, 30 seconds. Maybe it was really loud, and I remember being ushered out. But I couldn’t stop talking about it.

Then, I remember watching “The Ed Sullivan Show” with my family, and how we’d wait weeks to see a rock-and-roll band do the show. Then, after I saw the Stones and Beatles, I wanted to play the drums; I was the youngest of five kids, so making a lot of noise was part of the program!

I studied drums for two years, but at the same time, my sister, Marian, who is about five years older, started playing guitar. She had a nylon-string acoustic, and started to write songs. I got to see her perform at her school, and it was the strangest experience, watching her go through songs I’d heard in her bedroom or in the backyard. There she was, onstage. I remember worrying whether she was going to get through it okay. But I remember loving it, as well. I kind of connected that emotion to what I felt listening to that band in Vermont.

Also, my sisters’ boyfriends used to play records at our house. They’d ask me, “Hey, Joey. What do you think about this?” It would be Hendrix and Led Zeppelin, the Stones, and the Beatles.

So I started to get more into guitar, and I sort of turned into a Hendrix fanatic – I took to every Hendrix record that wound up in the house. And I started to go to shows; the first I saw was either Jethro Tull or Chicago Transit Authority at the Westbury Music Fair, on Long Island. It was all sort of happening around me. I was too young to experience the ’60s, but through my siblings, the records were handed down starting with the rock of the ’50s and leading up to everything that was happening from the beginning of rock through ’66, right up until ’70.

As my sisters would leave go to college or move out, their records would be left behind, and I absorbed all of it.

In Deep With Professor Satchafunkilus

A Look at a few of Satriani’s Guitars, Vintage and Otherwise

1955 Gibson Les Paul (1) The goldtop. When Mike Pearce brought that to me, I fell in love because of the way it sounded. But I also loved its look; it’s exactly my kind of guitar – totally beat-up look. Mike said, “I think this belonged to Steve Hunter,” which that added to its caché.It looked right and came in a case that had “Steve Hunter” on it. We were just psyched, because Steve Hunter is part of our rock-and-roll DNA. I was gonna get the guitar, anyway, just because it was a beautiful piece.

Fast-forward a year or so, and I’m onstage with Steve Hunter at a benefit for a friend. Afterward, I said, “Steve, I have this beautiful goldtop that used to belong to you.” And, right away he says, “I don’t know where the heck that started, but I’ve never owned that.” It was further proof that often in life, so much is in the mind! We look at an old guitar and if somebody says something like, “Jimmy Page owned this for a year,” your brain goes haywire and you start to think the guitar’s got more mojo. I have to remind myself, any time Mike brings over a guitar, to not buy something because it was once owned by someone or was once on the cover of Vintage Guitar or something!

1958 Gibson Les Paul Junior (2) Pierre de Beauport found that for me around the time of The Extremist. It and the ’58 TV Special started me thinking about collecting guitars not as primary instruments. I had my Ibanez model and knew it was the tool I’d need to express myself. But I started to realize that in order to create textures you’d call “classic rock,” you needed tools from that era. I’ve had quite a few Juniors and got rid of most because they didn’t compare.

1958 Gibson Les Paul TV Special (3) That is such a great player. I walked into Chris Cobb’s shop, Real Guitars, in San Francisco, one day, not thinking of buying anything. But there were two ’60s Strats – a ’64 and a ’61 – on consignment. I couldn’t believe it, I’d been looking for something like them for 10 years. So then and there, I bought them. Then Chris said, “If you’re in the mood for buying stuff, I’ve got my Special here.” He brought this thing out, and I could not believe it. I’d owned some nice ones, but they always fought me, as a player. This one, though, is amazing. Talk about mojo! I couldn’t believe how great it sounded and how easy it was to play. He had bought it from an old rock-and-roll player who told him he was the only owner. My neurosis kicked in, and I had to have it. So that was an expensive afternoon, as I walked out with three cases!

1960 Gibson Les Paul Special (4) The Cherry Red double-cutaway. I got that at Gruhn’s, in Nashville. I loved that guitar up until two weeks ago, when we did the photo shoot. I was like, “How come I haven’t played this recently?” So I plugged it into Sam’s half-stack there in the studio, and I just didn’t get anything from it. I was like, “Oh no,” which is the beginning of the reverse neurosis, where I tell myself, “I have to get rid of this because…”

What was your first guitar?

It was a Hagstrom III, white with a black pickguard – a very cool guitar. It had the smallest, most-narrow, finished neck I’ve ever played. I used it for a year and a half, and played my very first shows on it.

Do you still have it?

No. But on a Chickenfoot tour a couple years ago, a fan who knew I’d been looking for one brought one to a show for me.

What was your first amp?

A Univox U65Rn, I think. We lived a few miles from Plainview, New York, where Unicord was based. It imported or distributed Marshall at the time, and made a couple budget amps; mine was one of them – narrow 1×12, solidstate with reverb. Not very reliable.

I eventually got into a band with a guy who had a stack made by Lafayette, which was an electronics shop, like Radio Shack, on the East Coast. I believe his was tube. And our bass player had a Heathkit amp, where you buy the parts and build it yourself. Eventually, I wound up with a Fender Bandmaster. By then I’d sold the Hagstrom and found a late-’60s Telecaster with a maple neck. Someone had painted it black. I had a humbucker installed at a shop in New York City where Larry DiMarzio was working. That was my first brush with Larry, but I didn’t know who he was (laughs)!

Was that Tele your first good guitar?

It was great, had a Bigsby. With that guitar, I think I fell in love with the sound of wood, or at least understood what a guitar was supposed to sound like. The Hagstrom was just such an odd-sounding thing, had microphonic pickups, very thin and electronic-sounding. The only thing it had going for it was it was light, like an SG, and it had a great vibrato, much like what Brian May put on his guitars. So I learned how to do vibrato-bar tricks even before I knew much about music. I didn’t know modes or what was going on with chords, but I knew how to do dive-bombs, squeals, and make a fool of myself in front of my friends.

After that, I was in a band with a lead-guitar player named John Ricio, who took me under his wing and guided me toward the Tele, and eventually, a Les Paul Deluxe we found in the paper. The guy was wiling to trade for the Telecaster, which by then I had almost destroyed. The Deluxe’s mini-humbuckers made the transition from a Fender to a Gibson guitar a little easier.

What did you do to progress as a player?

I studied chord charts and my sister moved on, so I wound up with a couple of books. I’d bug my friends to write down all the chords they’d learned, so I had a couple loose-leaf pages with hastily drawn barre chords, and I’d play every chord on a piece of paper every day, over and over, figuring out how to connect chords to the music I was hearing on records.

At the time, I was going to a public high school – Carle Place High School – but it had an amazing music program headed by this guy named Bill Westcott. And I had to be in the school chorus, so I had to learn how to sight-read because we sang classical choral music. By that, time I was playing in bands that were doing Sabbath and Zeppelin songs, and I was taking a music theory class that was absolutely amazing; he gave us a college education in music. I graduated a half year early, so, the first part of my senior year, I took double courses of everything, including his advanced music-theory class that only had myself and another student in it. We covered everything.

So, while I was playing in bands doing free shows in the park and at parties, I was learning about Lydian-Dominant, how to sight-read and play piano. It was like I went to school in some small European principality – pretty remarkable, and Bill was a gifted young concert pianist who wound up at this small high school… poor guy! I can imagine him looking at me, a kid in motorcycle boots, black jeans, a t-shirt, hair down to his shoulders. All I wanted to do was play heavy rock. So, like a good teenager, I’d resist every time he’d try to teach me something! Eventually, though, we saw eye-to-eye and I wound up actually working with him; I played bass for these gigs he did in restaurants. He’d play standards – he was a brilliant piano player, could play any kind of music and turn any song into any style. I’d very lightly follow the lines around him.

I started to understand how you collect intelligence on being a guitar player. Not only with the music I was doing in school, but how to stretch a Rolling Stones song to 12 minutes at a backyard party, which was fun. My friends now tell me I took it very seriously! And I did spend a lot of time practicing. They’d tell me, “Hey, there’s a party over here.” And I’d be, “Ahhh, see you later.”

During this time, I went to three lessons with Billy Bower, who had a pamphlet of arpeggios and extended scales, which was just what I needed, because I was getting kind of overwhelmed interpreting music theory and trying to put it on the fretboard. This was right around the time I switched to the Les Paul Deluxe, because I remember practicing all that scale work, eight hours a day on it.

1958 Gibson L-5CES (5) I struggled with that guitar. It’s one of those where you open the case, look at it, smell it, and fall in love. But if I can’t figure out how to play good music on it, eventually it starts to bother me that I’ve got this expensive guitar and there’s 100 guys out there who could play beautiful music on it. Instead, it’s in my closet. That really bothers me. It and the Cherry Red Special are on the list labeled “Maybe I should sell them and find another Hagstrom III or something…” (laughs) Who knows?

1965 Gibson J-45 (6) I was in Caracas, Venezuela, one evening and a guy walked up to me in front of a restaurant and said, “I am such a big fan of yours, I would love for you to have this guitar.” So I said, “Well, thank you.” Great, you know? It has the adjustable bridge and is a beautiful guitar. I loved it immediately, and I wrote songs on it right away; I wrote “Bitten By the Wolf,” that wound up on the first Chickenfoot record. I think I wrote “Different Devil,” too, on the new Chickenfoot record. The bridge was a mistake for Gibson, but the guitar is a beautiful example of the magic they can create with their acoustics. I had Gary Brawer put on a new bridge, and man that guitar sounds great – best Gibson acoustic I’ve ever owned.

1966 Fender XII (7) Michael Pearce got that for me. I’d mentioned to him I wanted one. I had a Rickenbacker and he said, “A lot of people who say they used the Rickenbacker, actually used Fender XII.” So he shows up one day with this beautiful Candy Apple Red XII, and I put it on just about every record. It’s just an amazing-sounding guitar. I learned that it does what the Rickenbacker doesn’t – but it doesn’t do what the Rickenbacker does (laughs)! The Rickenbacker goes “twang” like nothing else. Put it into an AC30, turn it up, and it’s the ultimate “fairy dust” guitar, for if you need a little sparkle for a bridge or chorus. Anytime I have difficult parts to play that need to be mellow, and not overtly twangy, I use the Fender. There’s a song called “Cool New Way,” on the Super Colossal record that’s just guitars with harmonics – no chording – and I put the Fender on the left channel and the Rickenbacker on the right, and they complemented each other so well.

It led me to create the Ibanez JS-1200, and I actually took detailed pictures of this guitar’s finish and told Ibanez, “It would be nice to have a JS with this color.”

1990 Ibanez JS-2 Chrome Boy and Refractor (8, 9) I originally had three of these from that period, called Chrome Boy, Refractor, and Pearly. Pearly was stolen years ago while I was touring. The Chrome Boy was my favorite, while Pearly had a lighter tone, for some reason. The chrome finish really created a different tone every time a body was dipped in that material. Unfortunately, they used real chrome, and any fissures created when the finish lifted the sealant off the body would crack and create a knife-edge. So there’s a lot thick plastic applied to the guitar to protect my hands from being shredded by chrome dog-earring from the body. These sounded better year after year. At first, when the guys delivered the guitars, I remember thinking, “Boy, these sound compressed or something,” and I put them in the rack. And I don’t know if just being jostled around and exposed to stage volume every night sort of seasoned them, but later, they became my favorites, especially the Chrome Boy.

Do you still have that guitar?

No, I sold that, too… it followed me to Japan and California, and I traded it to Second Hand Guitars in partial payment for a ’54 refinished hardtail Strat.

Going back a bit, there’s a rather romantic, folklore-like twist in your history having to do with your reaction to hearing about the passing of Jimi Hendrix…

Yeah, that was very traumatic for me. I really loved Hendrix, and I didn’t realize just how much I did until I was told he had died.

It was an otherwise beautiful day in September, early days of the school year. I loved football, though I wasn’t a great player; I loved puttin’ on the gear and hittin’ everybody, running around. And I remember, very clearly, being outside the gym doors on the way to practice when a friend told me Hendrix died. I remember turning around and walking right into the coach’s office; coach Reddon was a wiry, intense ex-Marine who ran the gym like we were Marines. So I was kinda petrified, but I was going through this cathartic experience, dealing with the news. I remember blurting out, “Jimi Hendrix has died. I’m quitting the team. I’m gonna be a guitar player.”

To my surprise, he didn’t say anything to dissuade me. He just said, “Okay, bring your gear back.” That’s all I remember from that exchange because it was such a tumultuous moment in my life. I remember sadness, then going home and putting on Hendrix records. An hour later, with the seven Satrianis at the dinner table, I told my family what I was planning to do. There was shock and horror (laughs) in the kitchen! But my sister, Carol, had just finished her first week teaching art at a local high school, and she said, “Well, I’ll donate my first paycheck to get you a guitar.” So I had a budget, and eventually that Hagstrom fit into it. It was $120.

So you weren’t thinking about a Stratocaster?

I don’t think I knew what it was, to be honest. I don’t think I understood what Gibson or Fender or any of that stuff was. I just kind of looked at the shapes and knew Hendrix had a white one and a black one, and that’s all. Someone should have sat me down and told me what was going on!

Still, the Hagstrom looked cool, and it put me in “the club.” Most of the guitars in the local store were atrocious-looking, and I didn’t know where another music store was, so… (laughs)!

As your career progressed did you develop a preference for certain instruments?

Well, there was a long period of anxiety, like most players, about what I should play. I’d be in a band and have some sort of a Fender-y kind of a setup, then the band would change or someone would say, “You know, that doesn’t really sound like Tony Iommi or Jimmy Page,” and I’d have the wrong tool. And I couldn’t even think about having three or four guitars… or even two! I just had one. So making a leap to a Gibson was huge in terms of tone. You either played a Fender or a Gibson, and god forbid if you should switch to an SG or a Les Paul, then the band wants to do a lot of Hendrix. You’re kinda like, “Oh, no!” (laughs)

And I was dealing with amps that were not even remotely professional. I could never afford a Marshall, and loud Fenders were not part of my scene. I was lucky to have that Bandmaster! It was big, but didn’t make much of a sound. So I struggled with that. Once I started to play the Tele, though, I knew it was a real guitar and I started to understand what it could and couldn’t do. I guess that drove me to the Les Paul, but that was frustrating, as well, because I was familiar with all of the Tele’s Fender characteristics. So I flipped into a ’54 Strat, which was beautiful but had been refinished. So it had a gold-tint neck and the body was refinished in what we called “avocado sunburst.” The guy who did it was a true artist, it was beautiful. It had weak pickups, so it had beautiful sustain and very nice presence, and it was a hardtail, which was kind of interesting, and I really got into that. That was when I’d returned from bouncing between Japan and New York, and was setting down roots in Berkeley. I did a lot of teaching with that guitar, but I realized I needed to take advantage of parts being offered by different companies like Boogie Bodies and ESP. So I started to put together my own guitars with humbucking pickups with a bunch of electronics configurations. Those were my main guitars for four or five years.

1984 Kramer Pacer 10) This is the guitar I used for the first two solo albums, Not of This Earth and Surfin’ With the Alien. After I finished Surfin’, I went to a NAMM show and we started passing the album around. That’s when my relationship started with Ibanez; I was introduced to D’Addario and DiMarzio and, through Steve Vai, the guys at Ibanez. They said, “We’d love to make you a guitar.” And I said, “Please! Help me.” Because the Pacer was constantly falling apart or went way out of tune.It was unusual because it wasn’t a production model. I bought it at Guitar Center, and it was put together, I believe, in the back. It had a Pacer body, the neck was from some other Pacer, and it had a mixture of gold and silver hardware. The original Schaller pickups were long gone, I’d replaced them with Seymour Duncans or DiMarzios, and every couple of weeks there’d be something different in that guitar. At one point, back when Floyd Rose vibratos used to screw right into the body, the wood was so light the post would be stripped within a couple of weeks. I was so happy to stop playing that guitar (laughs)! It was rough. But it’s a cool part of my history.

1990 Ibanez JS 3 Donnie Hunt 11, 12, 13) I have three original Donnie Hunt guitars. Donnie was an artist in the Bay Area who passed away a couple of years ago. He taught art at the Oakland School of Arts and Crafts, and basically painted everything in his environment – his loft, his phone, refrigerator, shoes, jackets, whatever. I had him paint a couple of guitars, then took him to Ibanez, and they basically hired him. I think he painted 300 versions, all incredibly different. Donnie also did a lot of embarrassing clothing from my early career! It was thrift-store stuff – very difficult to clean on the road! I originally had four of them, but my favorite one was stolen.

What time period was that?

This was around ’78 through ’84. Then, somewhere in there, I picked up a Kramer Pacer with an original Floyd Rose without the fine-tuners. I was in a band called the Squares, which was like Van Halen meets the Everly Brothers – it was weird, sorta like Green Day, except we weren’t good (laughs)! We floundered, maybe because I was really bringing heavy metal and fusion; I liked the Ramones, but I liked Van Halen, so it was kinda mixed up, and the guys weren’t into it. My current drummer, Jeff Campitelli, who I’ve played with more than anybody, was in that band, and was more into traditional rock – definitely not into the stuff I was into! Our bass player was a whole other case. But during that period, the guitars I put together were fantastic for what we were doing. I needed something that took advantage of the Floyd Rose, and I was trying to develop a melodic solo voice, rather than just a wall of sound, which is what my guitar did in the band.

So you were right there early in the Superstrat thing…

Yeah, in the late ’70s, if you were a rock player, you were probably frustrated with the Fender vs. Gibson dilemma. I knew a hundred guys who were doing the same thing. And when Van Halen came out, we all went, “See! That’s what we’re talking about.” We felt kinda vindicated by Eddie. Suddenly, those weird Frankenstein guitars gained validity.

So, when did you start scoring cool vintage guitars?

It’s funny, when you talk about “scoring” guitars, I remember some that had jewelry-store value, but I could never connect with them. And others maybe have less value as collectibles, but they give me love year after year.

I have a ’58 Esquire with a Tele setup that a friend, Chris Kelly, found for me while I was recording The Extremist. I used it right away and it wound up on every record after that. Most of my other guitars have come from Mike Pearce, who in my address book is called “International Man of Mystery” (laughs)! I’ve known Michael for a very long time, he was actually a student of mine back when I was teaching at a guitar store in Berkeley. Fast-forward a couple decades, and he owns two music stores in Japan. But as we became friends, he wound up being this procurer of vintage and unusual instruments. My goal has always been to find great examples of great player instruments, so I can use them on records, and Mike educated me on all the elements.

I’ve had great Strats I never should have sold – mint and beautiful, but they just didn’t like me. I never played anything good on them. So I let them go.

Do you have any favorite guitars at the moment?

I used my ’59 ES-335 a couple of months ago on the new Chickenfoot record, for a song called “Somethin’ Gone Wrong.” We were looking at the song – it was pretty much finished – and our engineer/producer, Mike Fraser, said, “I’ve got an idea. Why don’t you put on a guitar and just kinda play some melodies wandering around? Then we’ll see if there are spots where we can mix it with Sam’s voice.” There was already a bunch of Ibanez guitars on the track, and I remember thinking, “Let’s just pull out the 335.” So I plugged it into the Marshall and got a very nice, warm tone out of it. So I just started wandering through the track. And when Mike mixed it, he kept all of it. I was shocked, but everybody who heard it was like “Wow, what is that?” It was just the perfect moment, the perfect suggestion, and the perfect guitar with the perfect amp. And I played in a way I’ve never played before; that guitar worked its mojo on me. I restrained myself just right, and it sounds huge.

Are there other vintage guitars in your collection that have similar stories or for which you have a similar affinity?

Sure. The ’58 Esquire. There was a period in the mid ’90s when I was into that thing so much. We used it extensively on The Extremist to do Tele-like things – add that sparkle. For the Time Machine compilation, we recorded three new songs, and I decided, “I’m just gonna play the Esquire.” I think we had Seymour Duncan pickups in it at the time – the thing has had about a hundred different pickups. I plugged it into a little 17-watt amp made by Matt Wells, then ran it through a vintage Marshall 4×12, and recorded three songs using it as the primary guitar – “All Alone,” the Billy Holliday song, a trio recording called “The Mighty Turtle Head,” and the title track “Time Machine,” where I used it for the rhythm parts. Then, I wound up using it quite a bit on Joe Satriani, which Glyn Johns produced. That was a bit rougher, because those were live recordings in a situation where I wasn’t sure what I was doing on some tracks, so you hear me struggling with the Tele.

The Telecaster is the one electric guitar you can never dominate, really. There are guys who come close, but most of the time, it has its way with you.

The Ibanez still figures heavily into your recordings…

Yeah, it’s on just about everything. And on tour I play strictly Ibanez guitars because I have so much catalog to cover, with melodies and solos using every conceivable technique. The JS (Satriani’s signature Ibanez line) guitars have been molded since ’88 to reflect this “job” I’ve fallen into. It’s the guitar that allows me to do all those things I can’t do with the Esquire or the 335, which goes out of tune after eight bars! The JS resolves the struggle – “Am I going to play Fender or am I going to play Gibson?” Instead of having to make a choice, I’ve got a 251/2″-scale guitar with humbuckers, compound radius, frets are just the way I like them, and its neck feels more vintage. But the guitar is like a modern sports car.

Do you have a favorite tone or setup?

I don’t think so. I’d say just about anything through a Marshall is really good. There are so many different ones, but the basic Marshall is the “kitchen sink” sound – it gives you everything. More than you want, maybe! It’s the most revealing amp you’ll ever plug into, I think.

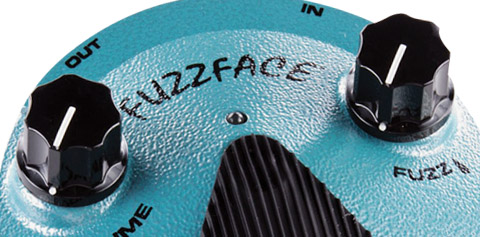

Early in my career, I tried to run from it. On the first couple of solo records… for Not of This Earth I didn’t even bring one into the studio. I was such a contrarian, I remember calling [recording engineer] John Cuniberti and saying, “I’m gonna use whatever is in the closet.” I thought that was a cool, artsy way of doing things. What happened to be in the closet was an early-’70s Pro Reverb, and I just plugged little (effects) boxes into it. We’d record quietly and use microphones like a C12A, Boss pedals, and early tube drivers made by Paul Chandler. Parts of Surfin’ With the Alien were done with a JC-20 and the DS-1 instead of the Marshall stack. We began to realize [the sound] had a lot to do with the mic and the relative tones of the other elements in the band, which was very liberating. You can say, “I need a Strat and a full stack. That’s the only thing that’s gonna make me rich, famous, and a great guitar player.” But history says, “No.” If you really look into it, you go, “Hendrix used a Tele on that song? And Jimmy Page played through a Supro?” You realize that all the great players and great albums were made with ingenuity, using unusual ingredients in terms of guitars and amps. Once you get that in your skull, you realize, “I can do what I want and I should use these tools in a creative way.”

I look at each song as its own little world, a concept I was introduced to through Hendrix and Page. I’d call them the opposite of the guitar hero who always wants to remind you of everything they can play and what their signature tone was. That wears thin on me after a song or two. Hendrix changed his sound for every song – he’d either play crazy or he’d play demure, whatever he needed to get something across. Page was the same. On some songs, his sound was small and thin, other times it was huge; sometimes it was only one guitar, sometimes he’d layer. It was artistic. I tried to carry that through my solo career, and with Chickenfoot I have a broader canvass to practice those influences.

In terms of your playing, is Chickenfoot more meat-and-potatoes?

The obvious main difference is there’s no singing in the solo gig. Melody guitar parts take the place of the vocals; the human voice is such an incredible instrument, and it changes everything, even the way the bass player and the drummer are playing. In Chickenfoot, I’m part of the rhythm section. We’re playing rock music, applying classic-rock stylings and kind of celebrating our roots. You can hear on the new record where I’m a Jimmy Page disciple until the solo, then you hear a real Jimmy Page influence. It’s kind of schizo, but it’s a support part and you can pick a lot of interesting colors that can contrast the meaning of the song. Because you’ve got lyrics, a singer, in this case Sammy, who’s delivering some kind of a message, and you can work off that in many different ways.

In an instrumental song, I don’t have the benefit of lyrics. So texture has to make that point to the listener. It’s very different. I think about “Wind In The Trees” from Black Swans and Wormhole Wizards. I was putting a melody on it and thinking, “I need something unique that can convey the feeling I had when I was a kid looking out my window in Long Island, late at night, watching the wind blow through the trees, and about what was ahead of me in life.” That’s a difficult thing to convey without lyrics.

Ibanez Futura14) Doug Doppler gave that to me as a gift a couple of years ago. Nice big piece of wood, I like that guitar. It’s really super-warm-sounding. I haven’t yet used it to record, but I keep it in the back of my mind as a great guitar for a slide part or something.

1948 Martin 000-21 15) That has an interesting bit of modification – a Sunrise pickup, which I used quite a bit on a couple of records. I asked Gary to replace the bridge and put on one of those two-piece saddles. We used it for “Starry Night” and so many songs where there’s an acoustic bed. Me and my son, ZZ… it’s our favorite acoustic in the house.

1969 Fender Stratocaster 16) That’s an all-original Olympic White/maple-cap Strat. It’s really beautiful; take off the pickguard and you see the original color, it’s pretty stunning. I used that for the melody on “Two Sides to Every Story” on my last solo record. Fender guitars had all sorts of tonal qualities in different years, as their pickups got hotter or weaker, they used different woods and stuff. I relate to the ’60s Strats more than I do to ’50s Strats. I was kind of brainwashed earlier in my collecting career, thinking, “You had to have a ’55 and a ’56 or whatever.” But after owning so many, and getting rid of all of ’em, my Strats now start at ’60 and I’m still looking for perfect examples of ’64 through ’69 models, because that’s what I heard on records when I as a kid.

1964 Fender Stratocaster 17) This guitar has “it.” You know how when you plug in a Strat, switch on the neck pickup, and play the G string at the 12th fret, you know right away if it’s got that beautiful tubular tone? Not too skinny, not too bright, but not dead. I plugged it in, played two notes, and I went, “Oh, this is it.” The ’61 sunburst Strat does not have that lead-guitar thing, but it has better rhythm sound than this one. That’s why I got both. I thought, “For one or two or three songs, these are gonna be the perfect guitars.”

Daunting, to be sure…

And somehow, it led me to use auto-tune, which is the weirdest thing for the melody, exploiting it… Not hiding behind it, but using it the way a guitar player would use a wah pedal. When the solo came, I looked for something different, and wound up using the Sustainiac pickup and Sansamp software.

The opposite happens in Chickenfoot, where there’s three guys in a room, Sammy in the vocal booth, and we just want to make our point, then and there, with a live track. It’s very different.

Whose idea was Chickenfoot?

I was the last guy in the band, so I’m gonna take a guess that Sammy brainstormed it! He very slowly pulled in Mike and Chad, and they’d been playing for about six months when he called me and said, “We’re playing in Vegas tomorrow. Why don’t you fly down and jump onstage for the encore? It’ll be fun.” And I thought that was what we’d be doing. So I went for a Sammy Hagar weekend, and by the time I walked offstage, we were looking at each other like, “Wow! We sound like a band. We should try this somewhere away from 5,000 screaming people and see of it works the same!” And that’s how it started.

You went in with no expectations?

None. I was busy, just about to go on tour. I’d just finished mastering Professor Satchafunkilus and had months of touring ahead of me. There was no time for another band. But this one worked for the right reasons; as soon as we played “I’m Going Down,” “Mr. Fantasy,” and “Rock and Roll” onstage, it was obvious we connected. There was that thing you always want – undeniable chemistry. We knew it was impossible – Sam was working on an album, Chad was about to go back to the Chili Peppers… It was an impossible idea, yet we pursued because it felt right.

As you see it, how does the second album compare or differ from the first?

It’s quite different. With the first, we didn’t know each other as well, personally, and it was successful because of our overwhelming enthusiasm. When we were finally on tour and reflecting on what we’d recorded, we thought, “Wow, I wish we would’ve spent more time on that.” Every week, we’d realize more about each other as players. In my case, I’d think, “Too bad I didn’t know that about Chad. I would have written more songs to exploit it.” As I got closer to Sam, I realized he’s got so much to offer, which I think is very important in a rock band, that you get to know the singer on a more intimate level, what they’re about, what’s bugging them and all that kinda stuff that’s part of rock music.

So as we got into the second record, not only did we have the experience of the first one, but we had become a touring band – had crazy jams, great times and horrible times. So we had more to bring to the party. And I had more to write about. We came in wanting to pull things out of each other. I told Sam I wanted him to sing in a lower register and get a more-intimate thing going with the fans. And he wanted me to go crazy more, loosen up. He wanted to hear more of what he saw me do onstage. So we’d exert those influences on each other, and I think we wound up with a much tighter album that sounds better, more like us. We developed a Chickenfoot sound, and we know what it is.

This article originally appeared in VG January 2012 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.