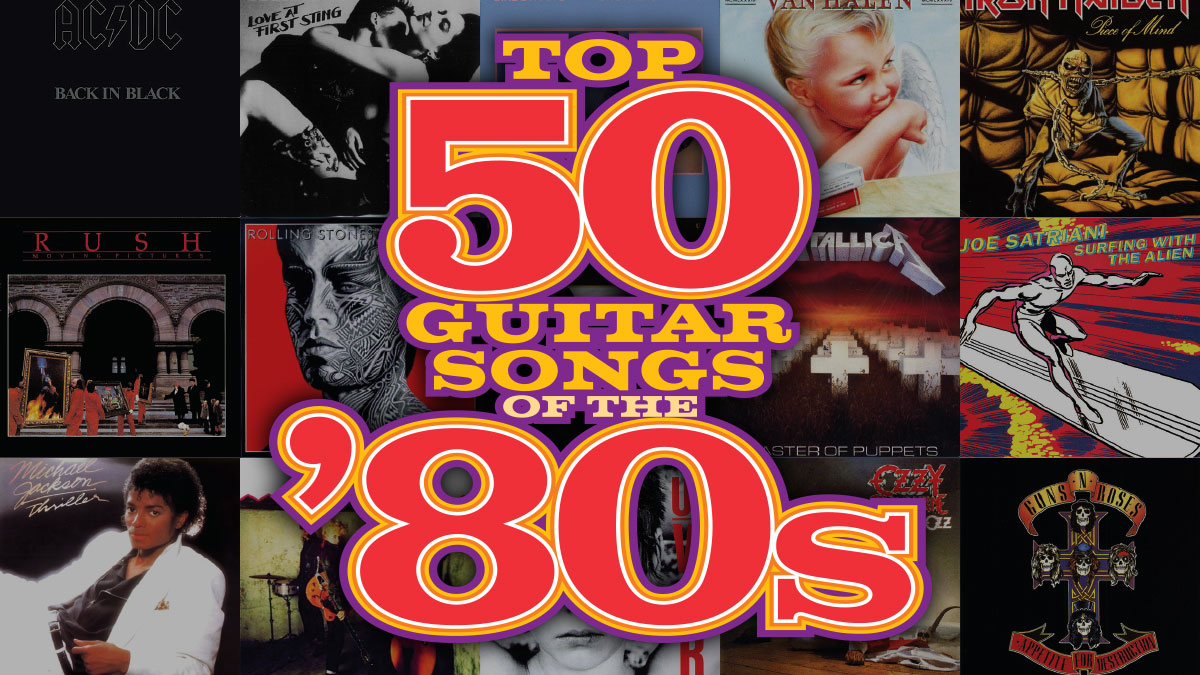

By the Readers and Staff of Vintage Guitar

Based on input from Vintage Guitar magazine staff and readers, this feature presents the results of a poll highlighting the 50 coolest guitar-driven songs of the 1980s, as chosen by our audience.

Check out our YouTube Top 50 Guitar Songs of the ’80s video playlist.

Check out our Spotify Top 50 Guitar Songs of the ’80s video playlist.

1 “Back In Black”

1 “Back In Black”

AC/DC, Back In Black, 1980

Though assailed by the increasingly popular synthesizer in turn-of-the-decade pop music, real rock bands stuck with what worked – guitars, bass, and drums – and none purveyed the spirit better than AC/DC. Loud, “dirty,” and quite capable of raising parental ire, the band churned out successive hit albums, all with their trademark catchy lyrics and hooks. “Excess” claimed vocalist/lyricist Bon Scott in 1979, and in terms of mass popularity, AC/DC peaked with Back In Black; the album introduced new vocalist Brian Johnson, and the title track – a fitting ode to Scott – is kicked off with Angus Young’s SG/Marshall setup delivering his famous driven-but-not-too-distorted tone with three chords that form a riff every aspiring guitarist learns, first thing.

2 “Crazy Train”

2 “Crazy Train”

Ozzy Osbourne, Blizzard of Ozz , 1981

Determined to show his ex mates in Black Sabbath he’d be just fine without them, Ozzy snagged L.A. guitarist Randy Rhoads to lay down licks on his first solo album. Nice call, there, Prince of Darkness! The quiet type, Rhoads’ spoke loudly with his musical ability and stylistic curiosity, which melded to make him one of the greatest players of his generation, and for this track, he created a riff that to this day remains atop the “gotta learn it” list for every kid with his first guitar.

3 “Sweet Child O’ Mine”

3 “Sweet Child O’ Mine”

Guns ’N Roses, Appetite For Destruction, 1987

Case study in how a hooky little lick – in this case played as a joke – can serve as the perfect setup to a great set of lyrics, which in turn inspire an equally remarkable guitar solo (or in this case, three!). With Guns guitarist Slash, things were never fancy. His style is meat-and-potatoes, his tone the tried-and-true Les Paul (well, back then, a Les Paul copy) through a Marshall, occasionally spiced with wah. And here, they combine on the first hit from what many consider the decade’s best album, the song’s intro serves as trademark not only for the band, but for the era.

4 “Money For Nothing”

4 “Money For Nothing”

Dire Straits, Brothers In Arms, 1985

Though glossier than previous Dire Straits hits, guitarist Mark Knopfler followed up this song’s synthy intro (and Sting’s haunting “I want my MTV” vocal line) with one hellaciously hooky riff that helped make the track the band’s best-selling single. Chasing a different tone, Knopfler eschewed his trademark Strat for this and instead used a Les Paul Junior through a Laney amp.

5 “Start Me Up”

5 “Start Me Up”

The Rolling Stones, Tattoo You, 1981

Perhaps the last great Stones lick – plied by Keef with his Tele strung just five-wide and tuned to open G – kicks off a song that was actually a cast-off from 1975’s Black and Blue album, where it began life as a reggae tune, and was bypassed again as a rock song when the band worked up 1977’s Some Girls and 1979’s Emotional Rescue.

6 “Pride and Joy”

6 “Pride and Joy”

Stevie Ray Vaughan, Texas Flood, 1983

With lyrics inspired by his relationship with a woman (not the same one who inspired his trademark instrumental, “Lenny”!), the track is a simple blues shuffle, dressed up considerably front to back by SRV’s glorious Strat tone (at this point played through a Marshall Model 4140 Club & Country and a blackface Fender Vibroverb). The first of his singles to chart, it introduced SRV to the masses – and his unmistakable playing style, from the intro to one of his best solos to the Freddie-King-inspired conclusion.

7 “Welcome to the Jungle”

7 “Welcome to the Jungle”

Guns ’N Roses, Appetite For Destruction, 1987

8 “Hot For Teacher”

8 “Hot For Teacher”

Van Halen, 1984, 1984

9 “Panama”

9 “Panama”

Van Halen, 1984, 1984

Van Halen at its artistic peak; the band’s final album with original vocalist David Lee Roth was arguably its best work. And these two tracks, especially, oozed the essence of that original lineup – whether in the form of Roth’s cocksure front-man style (in terms of both song lyrics and live performance) or the tightly syncopated interplay between brothers Alex and Eddie Van Halen.

10 “Hell’s Bells”

10 “Hell’s Bells”

AC/DC, Back In Black, 1980

The coolest riff on an album with a handful of the best ever played, the introductory blending of the sanctuary bell (does it toll for thee?) with Angus Young’s perfectly plied (and harmonically sinister) A minor, D/A, and C/A chords is sheer musical alchemy.

11 “Rock You Like a Hurricane”

11 “Rock You Like a Hurricane”

Scorpions, Love at First Sting, 1984

Germany’s entry to the heavy metal games were driven by two guitars, and most would say the combination that helped create this song – Rudolph Schenker and Matthias Jabs – were its best one-two punch. Schenker has long been a hardcore fan of the Gibson Flying V, while Jabs spent time on a Gibson Explorer or one of his modded Fender Stratocasters.

12 “Beat It”

12 “Beat It”

Michael Jackson, Thriller, 1982

In a stroke of marketing genius, Michael Jackson and producer Quincy Jones asked Eddie Van Halen – at the time, the undisputed king of rock guitar – to play a solo atop a viciously driving R&B rhythm. The end result became what every guitar geek knows is the best song on what happens to be the best-selling album of all time. Oh, and Steve Lukather’s rhythm-guitar groove ain’t bad, either!

13 “Master of Puppets”

13 “Master of Puppets”

Metallica, Master of Puppets, 1986

14 “Sunday Bloody Sunday”

14 “Sunday Bloody Sunday”

U2, War, 1983

A call for political peace in the band’s home country of Ireland, the song was a hit in the U.K. but didn’t catch on in the U.S. (beyond the college-radio crowd) until released as a video shot during a performance at Colorado’s Red Rocks Amphitheater. For most Americans, it served as an introduction to the Edge’s jangly, delay-fed guitar tone and melodic playing style.

15 “Surfing with the Alien”

15 “Surfing with the Alien”

Joe Satriani, Surfing with the Alien, 1987

16 “Jump”

16 “Jump”

Van Halen, 1984, 1984

17 “I Love Rock and Roll”

17 “I Love Rock and Roll”

Joan Jett & The Blackhearts, I Love Rock and Roll, 1981

A true rock-and-roll success story; the dark horse of the disbanded Runaways (Lita Ford and Michael Steele were supposed to emerge as the stars) covers a disregarded single by an all-but-forgotten British pop band to create one of rock’s greatest anthems. Gritty, in-your-face, and with an overt girl-takes-the-guy message viewed as empowering, it was number one on Billboard’s Hot 100 for seven weeks. Had Gibson been handing out signature models at the time, Jett’s Melody Maker might have been a best-seller.

18 “Texas Flood”

18 “Texas Flood”

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble, Texas Flood, 1983

19 “Rock This Town”

19 “Rock This Town”

Stray Cats, Stray Cats, 1981

The ’50s-inspired sounds of the Stray Cats certainly stood out in an age of ultra-modern synth-driven pop music. America’s first taste of the band (which released its first single in the U.K.) came via this track, with its fast-strumming intro setting up a sound and a song even your parents could dig! Guitarist/band leader Brian Setzer was – and remains – dedicated to the details; in the Cats, he used Gretsch guitars, usually a 6120, and usually with a (what else?) Gretsch vibrato that saw its share of work, along with a Fender Bassman or Princeton.

20 “Tom Sawyer”

20 “Tom Sawyer”

Rush, Moving Pictures, 1981

21 “Where the Streets Have No Name”

21 “Where the Streets Have No Name”

U2, The Joshua Tree, 1987

22 “The Trooper”

22 “The Trooper”

Iron Maiden, Piece of Mind, 1983

23 “You Shook Me All Night Long”

23 “You Shook Me All Night Long”

AC/DC, Back In Black, 1980

Yet another can’t-miss intro lick by Angus Young. Played anywhere even today, from basements to bars to arenas and by everyone from rockers to punks to country pickers, every person in the audience will know it – and start to groove in anticipation of the first rhythm chord.

24 “Livin’ On a Prayer”

24 “Livin’ On a Prayer”

Bon Jovi, Slippery When Wet, 1986

Introducing the talk box to a generation of rock fans perhaps not familiar with the work of Peter Frampton or Joe Walsh, Richie Sambora used it to augment a killer riff that sets up one of the catchiest sing-along choruses of the era.

25 “Couldn’t Stand the Weather”

25 “Couldn’t Stand the Weather”

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble, Couldn’t Stand the Weather, 1984

26 “Legs”

ZZ Top, Eliminator, 1983

27 “Limelight”

Rush, Moving Pictures, 1981

28 “Always With Me, Always with You”

Joe Satriani, Surfing with the Alien, 1987

29 “Stray Cat Strut”

Stray Cats, Stray Cats, 1981

30 “Paradise City”

Guns N’ Roses, Appetite for Destruction, 1987

31 “Forever Man”

Eric Clapton, Behind the Sun, 1985

32 “Cold Shot”

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble, Couldn’t Stand the Weather, 1984

33 “Ace of Spades”

Motorhead, Ace of Spades, 1980

34 “Rebel Yell”

Billy Idol, Rebel Yell, 1984

35 “She Sells Sanctuary”

The Cult, Love, 1985

36 “Photograph”

Def Leppard, Pyromania, 1983

37 “Purple Rain”

Prince and the Revolution, Purple Rain, 1984

38 “The Attitude Song”

Steve Vai, Flex-Able, 1984

39 “Another One Bites the Dust”

Queen, The Game, 1980

40 “Heat of the Moment”

Asia, Asia, 1982

41 “One”

Metallica, …And Justice For All, 1988

42 “Every Breath You Take”

The Police, Synchronicity, 1983

43 “How Soon Is Now?”

The Smiths, Meat is Murder, 1985

44 “Owner of a Lonely Heart”

Yes, 90125, 1983

45 “Don’t Tell Me You Love Me”

Night Ranger, Dawn Patrol, 1982

46 “867-5309/Jenny”

Tommy Tutone, Tommy Tutone 2, 1981

47 “Lenny”

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble, Texas Flood, 1983

48 “Gimme All Your Lovin’”

ZZ Top, Eliminator, 1983

49 “Breaking the Law”

Judas Priest, British Steel, 1980

“50 Round and Round”

Ratt, Out of the Cellar, 1984

This article originally appeared in VG July 2011 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Grammy-nominated guitarist Alex Masi has been maneuvering his way through the shark-infested waters of the music industry since the 1980s. With an impressive catalog that includes everything from high-intensity instrumental rock to covering Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, he keeps things fresh with diverse projects that push his artistry forward.

Grammy-nominated guitarist Alex Masi has been maneuvering his way through the shark-infested waters of the music industry since the 1980s. With an impressive catalog that includes everything from high-intensity instrumental rock to covering Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, he keeps things fresh with diverse projects that push his artistry forward.

Oz Noy is talented enough to pay the bills not only as a first-call New York session cat, but also as a prolific creative force in contemporary fusion. His current release is Twisted Blues Volume 2, and it’s the perfect bookend to the critically acclaimed first volume. In it, he turns the much-loved genre of blues inside out.

Oz Noy is talented enough to pay the bills not only as a first-call New York session cat, but also as a prolific creative force in contemporary fusion. His current release is Twisted Blues Volume 2, and it’s the perfect bookend to the critically acclaimed first volume. In it, he turns the much-loved genre of blues inside out.