Collaborations have rendered some of the greatest tunes in the history of music. Whittle the subject to “just” guitarists, and the truth remains – two are often better than one. The axiom is holding true for Susan Tedeschi and Derek Trucks.

Each a top-tier star in their own right, the two, now married for more than a decade, built careers on slow-but-sure arcs, along the way honing their chops and creating some of the best music to roll out of the blues and (in Trucks’ case) “other” genres.

Three years ago, both set aside their accomplished bands to form a musical alliance that more closely mirrors their personal lives. Despite the potential to alienate their respective fans, they liked the idea of starting fresh, and especially the chance to spend more time together and with their two children.

The Tedeschi Trucks Band will release its sophomore studio album, Made Up Mind, August 20.

Susan Tedeschi

Susan Tedeschi’s solo career has been marked by consistently strong material that established her as a force vocally and thanks to the Telecaster she so ably wields. She readily acknowledges the risk she and Trucks have undertaken in shedding their previous bands to form the TTB.

“When you make a change like that, not everybody is going to be happy. But we had been on the road for a good 10 years while being married to – but not seeing – each other.

“People understand that artists re-create themselves all the time; if you don’t, things get stale,” she added. “We want to keep learning and growing, working on new material, writing more, and learning more about each other,” she added. “Plus, we have so much in common, musically – we both love soulful R&B, blues, gospel, American roots music, and obviously, we share a love of jazz.

“In a lot of ways, I feel really blessed that Derek wanted to be in a band with me,” she added. “I think he’s an extraordinary guitar player; I can’t name a better one alive, really. And I’m not just saying that because I’m married to him (laughs)!”

Who most influenced your decision to play guitar?

I started playing guitar because my dad did. He taught me some folky blues chords on acoustic, but then I picked electric because I heard Magic Sam, John Lee Hooker, B.B. King, Freddie King, Otis Rush, T-Bone Walker, and Johnny “Guitar” Watson. They made me go, “Wait a minute…” So I bought a bunch of records and started to get obsessed. I kept discovering artists – Charlie Christian, Jimmy Rogers, Muddy Waters – Elmore James was a huge influence on Derek and me both. He could sing so beautifully and had this amazing tone on guitar.

Did you have a decent guitar right away?

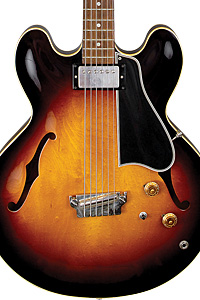

I was playing a Strat with a rosewood neck – American Standard, teal green/blue. It was my boyfriend’s at the time and he let me play it for about a year, then I bought my teal bluish-green Tele. I learned on those and I had a blond dot-neck reissue 335.

Not a bad crop…

No, and I actually started playing on my dad’s old Martin when I was 13 or 14. I switched to electric when I was 22.

Did you have a good amp right away – something to adequately complement the three electrics?

I had some weird little cheapy at first – a Peavey Bandit or something (laughs)! In 1993 or ’94 I bought a ’64 Deluxe Reverb and to this day it’s my favorite. We have tons of amps sent to us, and we both love that one. When I got it, it had original filter caps and everything. I played it for years then upgraded to a Super when I got into bigger clubs.

How did you and Derek decide who, from your band, would be brought aboard TTB?

Well, I suggested Falcon, who some people know as Tyler Greenwell (laughs), the drummer I’ve been playing with, because he’s wonderful – versatile – and I love the way he plays behind a singer, he’s sensitive to that and very easy to work with. He’s one of those people everybody loves and wants on their team. Derek had a couple of drummers in mind, too, so we gave them a shot. When J.J. Johnson came to the house, Tyler was playing and we had another drum kit next to him. J.J. sat down and they met right there, on the drums, in our studio, and instantly had a chemistry. J.J.’s a phenomenal drummer – one of the best studio players out there and has toured with Boz Scaggs, Doyle Bramhall, II, Gary Clark, Jr., John Mayer – you name ’em. When the two connected, that was really the start of the new group; it was Derek and I, the two drummers and the Burbridge brothers (Oteil and Kofi) – all these little pairings happening. There’s just a lot of chemistry amongst these musicians. They’re all so talented and can go in 100 different directions, so it’s never boring. And, everybody’s a lot of fun!

Was there much adjustment for you in the transition from solo act?

Yeah, I had to get comfortable with my position, you know? When you’re in a band this big – at first it was nine pieces, now it’s 11 – you’re playing for the songs, playing for the music, instead of playing to show off. It is a very tricky thing! When you’re a band leader, you’re in charge and you can choose whichever songs you want to do and twist it up. But with this band, I had to compromise – with my husband of all people! But, he’s on the money when it comes to music and I have a lot of faith in him and his decisions. If I don’t agree with something, we talk about it. I don’t play as much lead guitar now, obviously, because he’s in the band, and you go with your strengths.

So it’s been a learning experience, but it’s been amazing and really good for me. I still feel like I’m in the front – I perform like I would in a solo band, but a lot of the pressure is off. I don’t have to concentrate on guitar so much, so I can focus more on singing, which is a good thing. I play guitar most of the night and I get to solo on a lot of the blues stuff.

I feel really lucky to be involved with an improvisational, soulful, rockin’ band that’s always pushing and moving and growing.

How do you describe the new album?

It’s a bunch of great songs – very diverse. There are blues/rock songs like “The Storm,” where Derek gets a Hendrix feel at the end. There are anthemy, beautiful ballads… There’s just a mix of blues, jazz, and funk. “Made Up Mind” has an upbeat gospel attitude with a badass groove and a crunchy, fat guitar riff. “Do I Look Worried” starts out sounding like a Screamin’ Jay Hawkins tune but ends up being quite different. “Idle Wind” we wrote with Gary Louris, of the Jayhawks, and once the band played it, it became a different song. At first, it sounded folk-rock, then we put flute on the beginning, gave it a badass solo, and it became this whole other thing none of us could describe.

There’s a lot of dynamics on this record, and mixed genres creating sounds.

Is there one closer to something you might have done solo?

There is, and it’s funny because it’s one of the only ones I didn’t help write (laughs); my friends Sonja Kitchell and Eric Krasno wrote it and it’s called “It’s So Heavy.” The chords are sort of like something from The Band – folky, cool, simple, where it’s really easy to tell a story. And it’s dramatic, which I like, and it reflects the times we live in. It’s about how there’s a lot of changes going on. So, that kind of song is something I would play regularly.

A lot of the tunes I would do in my band, but I don’t know if I could have pulled it off the same way (laughs)! Some of them may be a little bit different, stylistically, but it comes from the same place – blues, rock.

Do you have a favorite track or two?

We released “Part of Me” as a single, and it’s a great tune. Doyle wrote it with us and came up with the melody, drums, bass, everything. We just had to write lyrics. It’s a really cool tune; it just feels like an old Motown song or something – upbeat and positive. People love that, plus it’s real danceable and fun. I also love “It’s So Heavy,” I love “Made Up Mind.” “Calling Out To You” is a really beautiful ballad. Eric has written for both records, and he started to write that song during the first record but there weren’t words until he got together with a friend. They’re beautiful and I love the story and the way it sounds.

What gear are you taking on the road?

I take my turquoise Tele. A couple of years ago, Derek asked me, “If you could have any guitar…?” I said, “Well, there’s two; a blond dot-neck 335, 1960. I’ve always had the reissue, and it’s awesome, but… And then, my birth-year Strat, 1970, and they’re sometimes hard to find and can be expensive. But Derek bought both; he’s insane! I’ve been playing the Strat every day. It’s sunburst, rosewood neck, and I love it, it’s gorgeous, sounds so warm and beautiful, really comfortable.

Those are on the road with you?

Not the 335 – I keep that at home. There were only 88 of those made. But I do take the Strat everywhere.

Which amps are you playing live?

I still play through a Super, and right now I have a ’65 that George Alessandro got working really well and hot-rodded a little. It sounds amazing. For backup, I use a reissue that works pretty well, too. It’s not as warm and the reverb doesn’t sound the same, but I just have to dial it up a little different.

How about pedals?

I use a Vox wah and a Moollon overdrive, made by a guy who gave some to Doyle and Derek when they were out with Clapton. I love it. I use it to boost solos.

What do you think of Derek’s playing?

Well, I love Clapton, I love Hendrix, I love Duane Allman, but, technically, Derek hits fewer bad notes than all three of them (laughs)! I find his playing inspiring, and to be in a band with him is amazing. TTB is our dream band – people who inspire us to keep pushing harder. If you set yourself with a lot of people smarter than you, whether in a class or a band, you do better things.

Derek Trucks

Derek Trucks has been hitting the stage with a guitar since he was nine years old, progressing from a Jay (not Kay!) acoustic to a Gibson SG. He briefly studied guitar with a family friend, but mostly learned by playing along with Eat a Peach, Fillmore East, Layla, and Elmore James records.

The nephew of Allman Brothers Band founding member/drummer Butch Trucks, he was barely a teen when he began taking the stage as a guest of the ABB. Though his proclivity for playing slide had him being hailed as the “second coming of Duane Allman,” he established a musical identity all his own and in the mid ’90s emerged with the Derek Trucks Band, unveiling a world-music bent. In its later stages, the DTB adopted a stronger blues/soul feel.

What was your first good guitar and amp?

My parents got me a pawnshop Yamaha acoustic, which was definitely better than that garage-sale Jay. My first electric was similar to the Jay – pretty terrible (laughs)! The first guitar I was really excited about was the SG, which I got when was 11 or 12. The first electric was cool, but the SG was the pinnacle.

Being so young, did you recognize the difference in the feel and quality of that guitar?

Yeah. Some of it was psychological – a guitar you’ve wanted so bad – so it’s automatically the best guitar you’ve ever played!

What amp were you playing through at the time?

The first amp I gigged was a Fender Super 60, one of those with red knobs, late ’80s/early ’90s. But one of the things about growing up playing the blues scene in Jacksonville was all the musicians had good vintage gear, including a lot blackface Fenders.

How old were you when you first first made a guest appearance with the Allman Brothers?

I was 11 or 12. The first time I played with them, though, was in Miami. I was backing Ace Moreland, a blues musician from Oklahoma who was living in Jacksonville, and we were playing at this South Beach bar called Tropics International, and the Allman Brothers were there, recording their reunion record – ’89, maybe ’90, somewhere in there. Greg [Allman], Warren [Haynes], Allan Woody, and my uncle, Butch [Trucks] came out and sat in. That was the first time I met those guys. I was nine or 10 at that point.

Which song did you do?

It was kind of a blur (laughs)! Probably “One Way Out” or something, but I’m not sure. A year or two later, our paths crossed in Atlanta, and I sat in with the Allman Brothers Band the first time.

Were you a little freaked out?

Yeah, pretty nervous. I didn’t know them except for my uncle, and they were mythical creatures, in a way.

But you eventually become a regular guest, then a member of the band…

I got the call to join in 1999, and I’ve been full-time with them since.

You met Susan when she was opening for ABB, right?

Yeah, the first year I was in the band was her breakout year. She was opening a string of shows, starting in New Orleans, and we met on the road.

Were you familiar with her music?

Not really. I had seen her name. I remember how, after [a Derek Truck Band] set, me and my bass player, Todd Smallie, were trying to hang out with these girls, and they were trying to turn us on to Susan’s music (laughs)! We were like, “Yeah, that’s great, whatever.”

Did you pay any attention to Susan’s set that night?

No, we were focused on the girls, but it just wasn’t happening for us (laughs)! They were adamant about us knowing about Susan Tedeschi. I met her not long after that.

What do you recall about the first time you heard her playing and singing?

I remember hearing about her before that tour, so Oteil Burbridge and I went out front one day during sound check, and I remember being shocked at her sincerity. I have a really low bulls**t threshold when it comes to music, and I was expecting it to be another, “Alright, that’s cute… Next!” (laughs) But she was entirely different, and you couldn’t deny what was there.

The more I got to know her and the more I’d see her perform, I saw that she had that thing great artists have, which is the ability to tap into a musical energy source. I don’t think you can learn it, it’s either there or it’s not.

What was the impetus behind the formation of Tedeschi Trucks Band?

At the time, I was seriously considering taking a break from my band, and also trying to convince Susan, “Now is the time if we’re going to do something serious.”

Herbie Hancock came to the house to have Oteil, Kofi, and [Derek Trucks Band vocalist] Mike Mattison play on a song he was doing. At that point, it hit me that we could take a stab at a larger band. I started thinking about how there were so many players I’d love to play with. And when you’re thinking about a band, you have to consider chemistry and who will make it fresh and different.

What did you consider as you chose members?

A lot of things. I’d been thinking about it for a long time, and we were going to start small, but then I was thinking about the Burbridge brothers – how there’d be something great about having siblings and a married couple in a band. So it was Oteil and Kofi, me and Susan, and we were talking to Charlie Drayton about drumming, but the scheduling didn’t work.

I remember hanging out with Doyle Bramhall a lot on the Clapton tour we did together, and he recommended J.J. Johnson as a drummer. But I also knew Susan was really comfortable with Tyler, and I wanted a piece or two in the band Susan wouldn’t have to think about when we played, because it was going be so different. This was from scratch, and we were going to re-learn how to push the boulder uphill. So I thought having somebody she felt really comfortable with would be great because, standing up front and being the lead singer, she needed total confidence. When J.J. showed up, we were rehearsing and Tyler was on one of the drum sets, but J.J. sat behind the other and, before any introductions were even made, fell right into the fold. It was a pretty great moment, and there was total musical respect – two people who listened, no jockeying for position – and it has remained that way. Their chemistry said it all. That’s when I realized that we were onto something, and once you have that solid base, you can start thinking about other things. Mike [Mattison] always factored in for me, he’s such an amazing songwriter and presence. It’s hard to find great musicians who are sane (laughs) outside of music and I’ve always appreciated the way Mike’s mind works – his organizational skills, the way he thinks about tunes… the big picture. So, I’ve always loved the idea of having Mike being a part of this. More than just singing but kind of behind the scenes a little bit more. He was a big help along the way – a great sounding board.

In any band, it’s difficult and you have to make sure it stays on the right path, but this is a bigger task than anything I ever been a part of.

Speaking of staying on track, Oteil quit the band last year. Were you surprised?

It wasn’t a shock. When you’re the one dealing with everything the whole way through, you see and feel things coming. For a lot of the band, it was a surprise, but one of the jobs as a bandleader is dealing with that stuff. And while it’s not always the case, with most major changes I’ve dealt with, it’s for the better. If things aren’t right – if somebody’s torn and they want to be home and not on the road… well, with a band this big, you’ve got to either be in or out.

Focused.

Yeah, it’s the only way. And I understand the pull to be home as much as anybody; I have kids, and I’ve been doing this since I was nine years old. But to truly make something go, you’ve got to give a part of who you are and what you do. Everybody’s in a different stage of their life. Stepping away has worked out well for Oteil, I know he’s in a better place not having to wear multiple hats. And for the band, it’s been a blessing. The new record happened in the middle of it all, and I think it’s the strongest thing anybody in this band has been a part of. It wouldn’t have happened the same way if that change wasn’t going on.

You filled his spot on the album with some great players…

Yeah, Pino Palladino, Bakithi, George Reiff, Dave Monsey – it’s been an amazing experience to have some of the greatest bass players on Earth contribute. It shows what makes a band special when you’re playing with different people. And that’s not to say it hasn’t been challenging, but I think that’s what separates a “real” band (laughs) is dealing with stuff like that. When it went down, I thought about the Allman Brothers. I was like, “Wait… They lost Duane and Berry. We can deal with this.”

Going in, my thinking was, “Let’s play with a bunch of different people.” After a relationship, you rebound with a bunch of hot chicks (laughs)! We’re gonna do that with bass players. So, we called some of my favorites.

Are any of them looking for a permanent gig?

As a band, we’re going to have a heart-to-heart. It’s a pretty exciting prospect, diving all the way in, and we’ve had an amazing run of players on the road. It’s a good position to be in, for sure.

Made Up Mind has a nice mix of soul, blues, R&B, and some roots-rock. In your mind, what kind of music it?

It’s been a while since I thought of our music in stylistic terms. It’s all the music we’ve digested up to this point, all the music we’ve played. It’s influenced by my group, by Susan’s bands, years on the road with the Allman Brothers, the things J.J. has done, my time with Eric Clapton. There has been some maturation. In a way, it feels like the first definitive statement this band has put on tape. Revelator was us finding our way around in the studio, and the live record was us starting to realize the potential. But this is the first time we went into a project with full confidence, thinking “The songs are good, this is just gonna happen.” When I talk about it, it’s more a general excitement I have that explains what it is.

Did the band work the songs on the road, or did you come in pretty fresh.

A few of them were played on the road, but I do love coming in with the band hitting it fresh – everybody sinking their teeth into the songs for the first time. Once we got comfortable with an arrangement and everybody had a feel for their part – which usually happened by take two or three, occasionally take one – we got a pretty good take quickly. I like the idea of the birth of a song being captured on tape.

What are some its highlights for you, personally?

There are quite a few. I think there’s some really amazing vocal moments – the sentiment behind “It’s So Heavy” and what was going on, personally, plus it has an amazing, heartfelt lyric, and the delivery is as honest as it gets. The way “Idle Wind” came together, the way it felt and sounded from start to finish, feels really good. Tracking “Sweet and Low” was one of the few times I’ve been in any situation where, when the last note finished ringing, everybody on either side of the glass knew that was the take. It was a pretty amazing moment.

I’ve listened to it a lot, between mixing and mastering and putting it down, and little things poke out at different times – the horn section, Kofi’s amazing keyboard stuff. He’s kind of the unsung hero of this whole thing.

Do you stay consistent with your gear?

Yeah, but in the studio I take more liberties. At the beginning of each tune, I have a sound in mind. Me, Jim Scott, Bobby Tis, who’s engineering it with us, go into the room and play the riff or the theme of the song and try to get a sound. Sometimes, you plug into what’s tried and true – a blackface Deluxe – and you’re like, “Yeah, that’s good… Maybe a little boring. Okay, let’s try something else.” (laughs) And on quite a few songs we ended up playing through an old Ampeg B-12 or B-15, switching back and forth, totally pinning it. “Whiskey Leg” was a Firebird through the B-12, “Made Up Mind” was my SG through the B-12, and it’s an amazing sound. I had never used that rig before, but there’s something about being able to play low strings and getting everything you want out of them. Playing through a bass amp was a nice revelation because if I want to capture the low-end of the guitar, I usually have to record it somewhat quiet – you can’t push the amp too hard. But when you’re playing through an old bass rig, you can give it whatever you want and it will deal. That was fun.

Which other guitars did you use?

The 335 on a few of the tunes, like the solo stuff on “Part of Me” and “All I Need.” Doyle Bramhall (II) is playing the same 335 on the main rhythm of “Part of Me.” The acoustic stuff is a converted ’30s Martin 0-17H on “I’m Calling Out To You.”

What’s the story with that guitar?

A good friend, David Drake, is really into acoustic guitars, and he started bringing instruments for me to play. I was recording with John Leventhal, and he had a handful of magical-sounding acoustics – that was first time I really got excited about a vintage acoustic, and I mentioned to David the models and years, and he perked up and said “I know where to find those.” He’d go and find these amazing instruments, and when I go to New York for the Beacon Theater run with the Allmans every year, we go on an acoustic-guitar search (laughs) and try to find something we might need for the studio or the road. He has found some amazing instruments – old Gibson acoustics, that magic Martin 0-17H.

Is the Firebird vintage?

Yep. It’s a sunburst IV from ’65. It’s a great-sounding instrument.

Do you use any vintage SGs?

Yeah, I have a really nice ’61 that I love, and not too long ago I got Johnny Jenkins’ old SG, the one he played on Otis Redding’s “These Arms of Mine.” He broke its headstock at the Atlanta Pop Festival, and I think Capricorn Records bought the guitar from him, had it fixed, and it was in Savannah, Georgia, for years. It’s a pretty amazing guitar. He took a soldering iron and wrote his name in cursive on the front – really beautiful script. It’s part of the Allman Brothers/Capricorn/Duane/Otis Redding lore. It lives in the studio.

And you and Gibson developed your signature SG…

Yeah, and it’s what I use, for the most part. we’ve been working on an updated version. For a while, I was playing a ’63 reissue that I put a stoptail on, but left the big piece of metal (from the Maestro vibrato) on because it looked nice. I used it for a long time, so they did a version of that. They’re doing a new one.

What about the 335 you use in the studio?

It’s a Cherry Red ’65 I bought on the road early on when I was playing with the Allman Brothers.

Is it set up standard or do you have to do any modifications to play slide on it?

No, the track I used it on wasn’t with slide, but I was tuned to open E.

This article originally appeared in VG October 2013 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

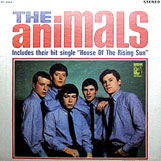

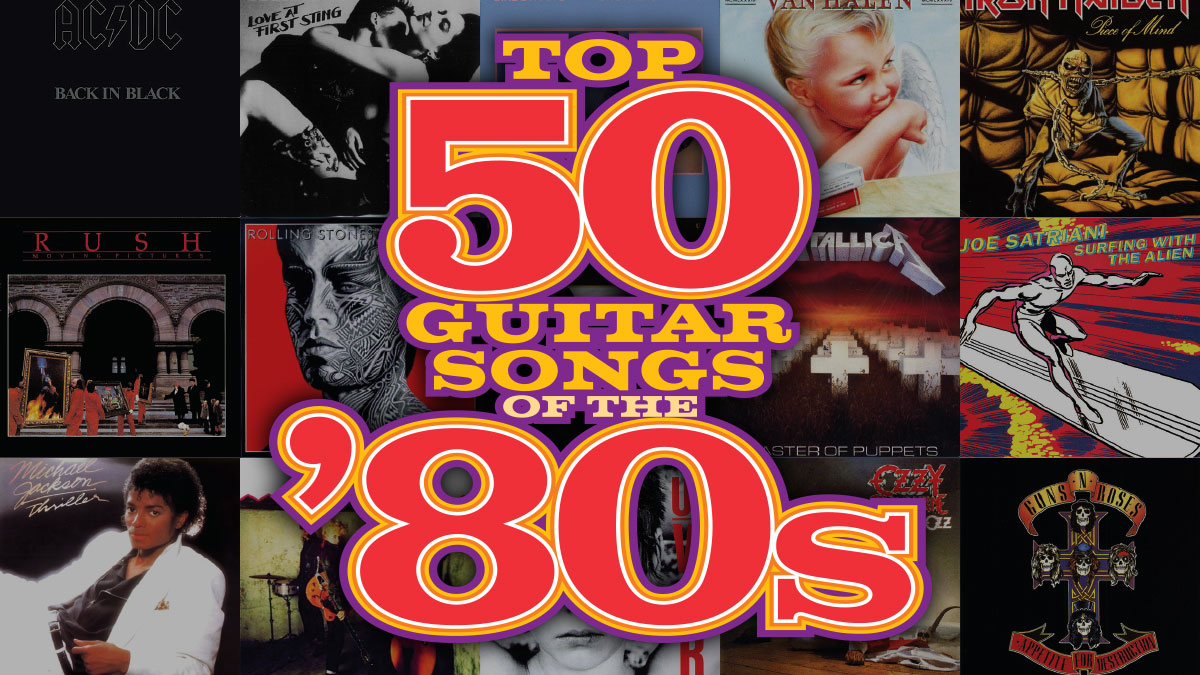

Vintage Guitar marked 25 years of publication with a year full of cool features that relied on feedback from readers who visit VintageGuitar.com. This month, we kick things off with the results of a poll to determine what readers believe to be the 50 coolest guitar-driven songs of the 1960s (VG added a bonus 25 for the online edition). The online poll told them it, “…could be an instrumental, could be a blues classic, could be a pop tune with a killer riff or solo.”

Vintage Guitar marked 25 years of publication with a year full of cool features that relied on feedback from readers who visit VintageGuitar.com. This month, we kick things off with the results of a poll to determine what readers believe to be the 50 coolest guitar-driven songs of the 1960s (VG added a bonus 25 for the online edition). The online poll told them it, “…could be an instrumental, could be a blues classic, could be a pop tune with a killer riff or solo.”

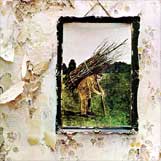

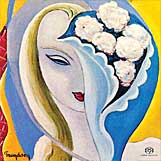

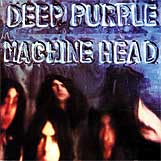

Vintage Guitar marked 25 years of publication with a year full of cool features that relied on feedback from readers who visit VintageGuitar.com. This month, we offer the results of a poll to determine what readers believe to be the 50 coolest guitar-driven songs of the 1970s. The online poll told them it, “…could be an instrumental, could be a blues classic, could be pop tune with a killer riff or solo.”

Vintage Guitar marked 25 years of publication with a year full of cool features that relied on feedback from readers who visit VintageGuitar.com. This month, we offer the results of a poll to determine what readers believe to be the 50 coolest guitar-driven songs of the 1970s. The online poll told them it, “…could be an instrumental, could be a blues classic, could be pop tune with a killer riff or solo.”

Grammy-nominated guitarist Alex Masi has been maneuvering his way through the shark-infested waters of the music industry since the 1980s. With an impressive catalog that includes everything from high-intensity instrumental rock to covering Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, he keeps things fresh with diverse projects that push his artistry forward.

Grammy-nominated guitarist Alex Masi has been maneuvering his way through the shark-infested waters of the music industry since the 1980s. With an impressive catalog that includes everything from high-intensity instrumental rock to covering Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, he keeps things fresh with diverse projects that push his artistry forward.