Info: www.winfieldamps.com

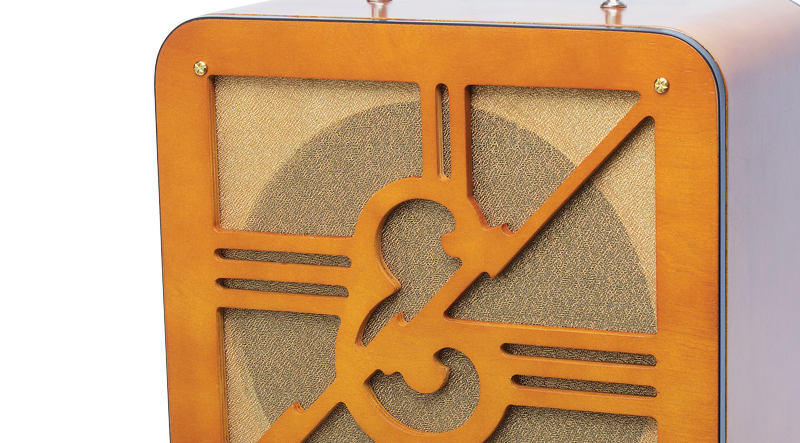

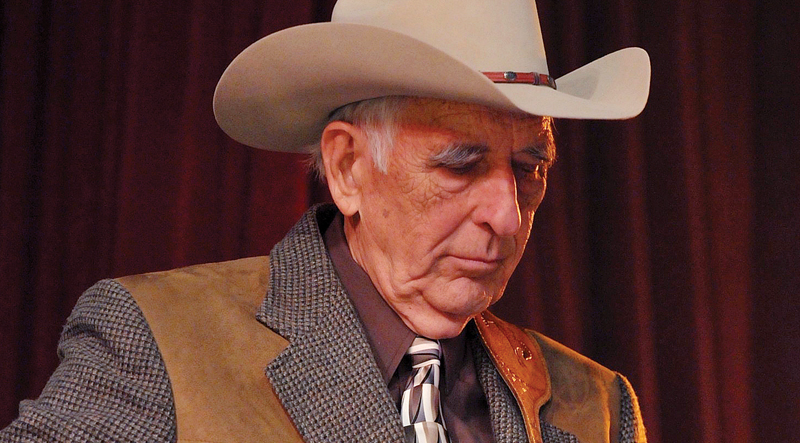

Unlike most amp builders who take up the challenge to create amplifiers that replicate the sounds of the 1960s, Winfield Thomas was actually wielding those sounds as a musician in the mid-’60s. Over the years since then, his amp designs have impressed. He’s created a line of hand-wired beauties utilizing circuit boards, Teflon wire, and modern components. Still, his amps harken back to his youth – simple, straightforward, and oozing complex tones, Winfield amps exhibit the aural template and old-school workmanship of a bygone era.

Winfield’s Dust Devil 15-watt combo is one such model, and it’s a rock-solid tone monster. The master volume-controlled two-channel Dust Devil has just enough modern bells and whistles to be dangerous. It also provides a powerful base tone for pedals and simply rages as a plug-in-and-go blues beast. Voiced with American attitude and EQ flexibility, Channel One features 12AX7 preamp tubes controlled by Loudness One (volume), Treble, and Bass chicken knobs. This channel is advertised as the classic ’60s clean, blackface side of the amp spectrum.

Channel Two, or the Cyclone Channel, is Winfield’s interpretation of the UK amplifiers of the same era. (He offers a standalone version of this amp as well.) This channel uses EF86 preamp tubes and features independent Loudness Two (volume) and Tone knobs. Combined with a 5AR4 rectifier tube, two EL84s, and one 12AX7 (phase inverter) in the power section, the Dust Devil covers a lot of ground in the low-wattage realm. A Cut control, a push/pull knob to engage the Master Volume, and an External Speaker input complete the appointments. Oh, yeah – it’s also lightweight and handsome without any prissy affectations, and its single 12″ Celestion Alnico Blue speaker perfectly complements each channel.

At 34 pounds, the Dust Devil combines a rugged British personality with American sonic colors. With the help of an A-B-Y box you can engage either channel, or both for some wicked tones. It’s a loud 15 watts that will work well with a full band but get a good workout against a loud drummer. More importantly it makes the perfect recording amp where the nuances of timbre and texture are under a microscope.

Voiced dark and crispy in the best possible way, Channel One excels in fat, lustrous clean tones for rock and blues. Thicker-sounding, more substantive, and more consistent than an elderly Deluxe Reverb, the Dust Devil is the perfect example of what rich-sounding boutique rigs are about. It’ll fatten the dinkiest Telecaster and offer Strats bark and growl. Though it’s not suited for pristine funk or jazz, reining the Devil in with your guitar’s Volume control will get you close. Cranking the Loudness control elicits beautiful harmonic overtones, and the EQ, while not overly dramatic, gets the job done.

Plugging into Channel Two the differences are subtle. The British side offers more percussive attack. The Tone knob helps quell or enhances this attribute, while the Cut knob works great for fine-tuning EQ. With the preamp section cranked and the pulled Master Volume lowered to room temperature, all manner of woolly mayhem will ensue from either channel. Channel One gets the win in the truculence department, but Channel Two has more clarity.

Winfield’s Dust Devil is a nice piece of craftsmanship that does what it was designed to do. It lacks crystal-clean headroom, but that’s for another kind of amp.

This article originally appeared in VG June 2017 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.