The gloriously soulful music recorded by Stax Records is still entertaining listeners six decades after its release, and the label has been celebrating its 60th anniversary with a reissue campaign. The first offerings are 10 Stax Classics compilations from artists including Booker T. & The MG’s, Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, Albert King and others.

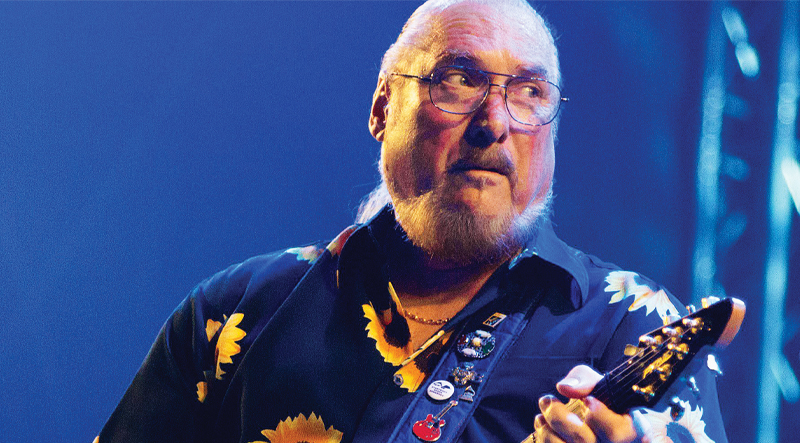

Central to the story is guitarist/songwriter/producer Steve Cropper. “The Colonel” was a member of Booker T. & The MG’s, best known for the 1962 instrumental “Green Onions” and as the house band for most of the label’s music.

“I have my theory on what made Stax and Memphis music great,” said Cropper. “Every time I look at my wife at a concert and we see people dancing, I’ll say, ‘You know why that was a hit, don’t you?’ and she’ll say, ‘Yeah, because you can dance to it,’ and I’ll say, ‘Exactly!’”

Cropper is still a busy man at 76, though due to his success – he also co-wrote and/or produced/co-produced standards like Wilson Pickett’s “In the Midnight Hour,” Eddie Floyd’s “Knock on Wood” and Otis Redding’s “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” – he can work when he wants. He’s been promoting Stax’s anniversary and the 50th anniversary of both the legendary Stax/Volt European tour and Redding’s scorching set (backed by The MG’s) at the Monterey Pop Festival.

Since Booker T. & The MG’s backed Stax artists, a certain stylistic feel was inherent, but they strived to make the other artists’ music different so it didn’t just sound like a guest vocalist or instrumentalist.

“The best example is Albert King, who became the most-famous blues guitar player of all time. Listen to any of his records then to the records we made with him. We took what he was doing and made it dance blues. We just brought it up a notch,” Cropper said. “That energy, I think, is what sold Stax music.”

Though responsible for so much fantastic music, Cropper is still electrified when he hears it on the airwaves.

“I think the most excitement and the biggest thrill you will ever get out of being a musician or a songwriter is hearing either something you’ve played on or wrote when it’s on the radio,” said Cropper. “That’s a thrill you just can’t explain to people. That is the ultimate.”

Those heady early days at Stax directly led Cropper to this point in his life and career. Stax music mattered then and still does now.

“You can’t hold that music down,” he said. “It’s too good.”

These days, he tours regularly with The Original Blues Brothers Band and the group’s new album, The Last Shade of Blue Before Black, is set for a fall release. Cropper and saxophonist Lou Marini ground the band, which was conceived by “Saturday Night Live” comedians Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi. 1980’s musical comedy The Blues Brothers is a beloved cult classic.

“A lot of people don’t know this, but the basics of the Blues Brothers band that played on the first record, Briefcase Full of Blues, and did the movies had done two albums and two world tours with Levon Helm & The RCO All-Stars,” said Cropper.

Early in his career, he was known for playing a Fender Esquire and Telecaster. Cropper said the guitars didn’t distort, and engineers and producers preferred the way their clean tone cut through on songs’ backbeats.

“I liked the Tele because it had two pickups. It was a little more versatile than an Esquire, which had one pickup,” said Cropper.

His main guitar for the past nine years has been a Peavey custom.

“It’s a one-of-a-kind Telecaster copy and it’s laminated so it’s very light. It’s a solidbody, but it’s all been hollowed out and laminated. It’s a great guitar. Great tone,” he said.

Cropper also had a Peavey signature model, the Cropper Classic, created because he envisioned a quality, affordable Telecaster-like guitar for beginning guitarists.

“I spoke with Hartley Peavey and said, ‘I need to put a Tele-style guitar on the market for under $1,000.’ He said, ‘I’ll build that guitar for you.’ It’s not a cheap guitar,” said Cropper. “I’ve got fan mail that said, ‘I bought it because it had your name on it, and now it’s my favorite guitar. I take it everywhere I go.’”

Cropper isn’t much of a collector and he’s not much into acoustic guitars, but when the economy tanked nearly a decade ago, as an investment for his children he bought several Gibson J-200s that people were selling. He also has a Gretsch Chet Atkins model given to him by The Who drummer Keith Moon.

This article originally appeared in VG January 2018 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Katana amps also have USB outputs to access the Boss Tone Studio effects editor via computer. Hooking the amp to a PC or Mac also allows downloading new sounds from the Tone Central website and tweaking up to 55 customizable effects. There are 15 default effects and you can use three at once. The best part is that you can save the effects, tone, and EQ settings for instant recall using the Channel Preset buttons. Players can purchase a separate Boss GA-FC foot pedal to access sounds quickly at gigs.

Katana amps also have USB outputs to access the Boss Tone Studio effects editor via computer. Hooking the amp to a PC or Mac also allows downloading new sounds from the Tone Central website and tweaking up to 55 customizable effects. There are 15 default effects and you can use three at once. The best part is that you can save the effects, tone, and EQ settings for instant recall using the Channel Preset buttons. Players can purchase a separate Boss GA-FC foot pedal to access sounds quickly at gigs.

On the job, the Bias Head offers a vast assortment of tones even without loading software. Pull up fat cleans or hairy distortions with ease and, when you find a sound you like, save it with the blue LED button. The real magic is when you link it to your computer or compatible mobile device using the app and Bluetooth. Adjust parameters to your own taste, download other guitarists’ presets, or record other amps and adjust them with the ToneMatch software.

On the job, the Bias Head offers a vast assortment of tones even without loading software. Pull up fat cleans or hairy distortions with ease and, when you find a sound you like, save it with the blue LED button. The real magic is when you link it to your computer or compatible mobile device using the app and Bluetooth. Adjust parameters to your own taste, download other guitarists’ presets, or record other amps and adjust them with the ToneMatch software.