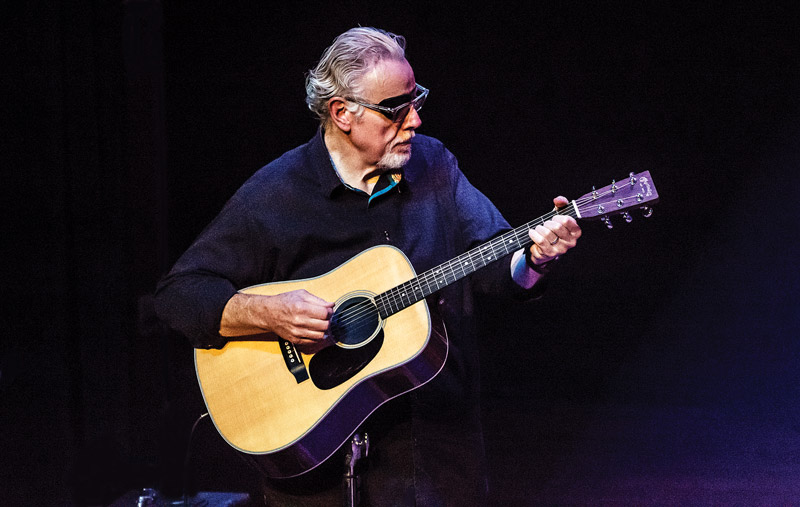

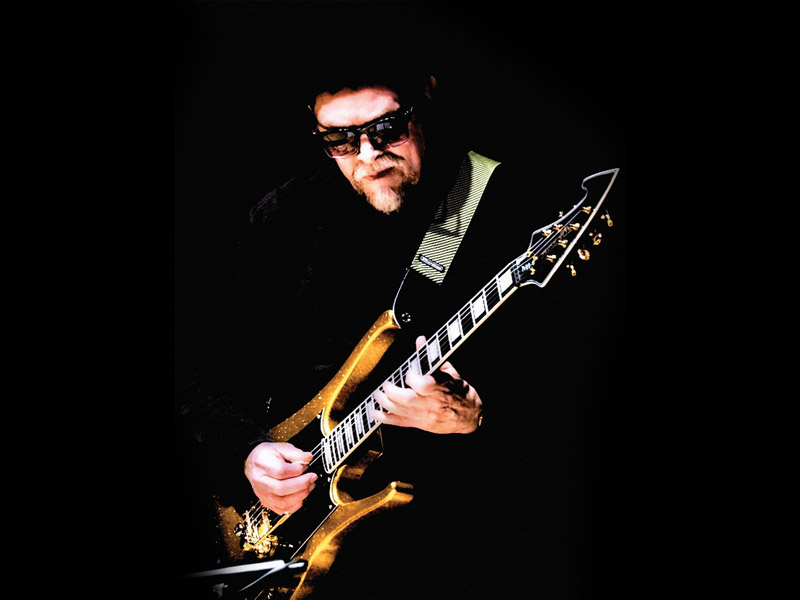

Phil deGruy is the rare jazz artist who’s also a bona fide entertainer – and a funny one, at that. His flashy, inventive playing is complemented by amusing asides and lyric parody. In fact, his observations on modern life could qualify for any stand-up comedy stage.

His unorthodox instruments attract the musicians in every crowd, but his overall mojo is the result of years entertaining at the grassroots level. Based in New Orleans, deGruy’s search for career nirvana included stops in Los Angeles and Nashville. Moreover, he studied with Ted Greene and Lenny Breau, the latter of whom once insisted deGruy (pronounced “degree”) give an ad hoc performance for Chet Atkins.

“I was living in L.A. when I heard Lenny was teaching in Nashville,” said deGruy. “So I made the drive. We hung out for about week, and I studied with him. Unfortunately, that was a dark time for him because he was a serious abuser. But, four years later I was going through Nashville again and heard Lenny was in town. We got together and played, then he said, ‘Chet’s got to hear you.’ And while we were at Chet’s place, Les Paul called. So I was immersed in all that.”

Even though his abilities can surprise all except regular fans, deGruy is modest enough to know he’s onstage to entertain. He’s perhaps New Orleans’ best-kept entertainment secret. In addition to stage presence, he discloses chops nurtured by Ted and Lenny, both integral parts of his backstory. And of course there were thousands of hours in the woodshed.

deGruy can hold his own with anyone from Tommy Emmanuel to Pat Metheny, but it’s not his style to challenge all comers. He’s an affable, astute guy who Greene said, “has chops for days.” And he presents a show that furthers his stature as one of today’s few true bon vivant players – one who’ll grab the attention of any musician within a hundred city blocks. His work is steeped in tradition, but edges the needle toward the red.

deGruy believes talent develops more naturally when it’s nurtured early, preferably from a musical family.

“I was 11 when I was forbidden to play our family’s guitar,” he laughs, remembering how his older brothers eventually tired of the instrument while he quickly grew to love the attention gained by playing it at school. “The Beatles and Clapton were the match, Chet was the fuse, and Lenny was the bomb.”

Many of today’s prominent players profess amazement and admiration for deGruy’s magic. His under-the-radar brilliance has impressed many heavies who’ve invited him to share the bill at their concerts. For instance, he recently contacted Steve Vai with a guest-list request for the rocker’s New Orleans concert. Instead, deGruy found himself opening the show and enjoying a killer jam at the sound check.

“Phil sounds like John Coltrane meets Mel Brooks at a party for Salvador Dali,” Vai told photographer Bob Barry in his new book, John Pisano’s Guitar Night, which documents two decades at the annual event considered a rite of passage for those in the Los Angeles jazz-guitar community.

He’s also shared bills with Andy Summers, Todd Rundgren, Stanley Jordan, Michael Hedges, Eric Johnson, Steps Ahead, Tuck and Patti, and Charlie Hunter, who turned deGruy on to using a fanned-fret instrument.

deGruy’s guitars are obviously unique and he went through a series of seven-stringed instruments. His first was from New Orleans guitar maker Jimmy Foster, but now he plays one made by Ralph Novak, inventor of the fanned-fret system.

“Ralph really created the ergonomics I needed,” he said. “I have a longer bass string, yet a shorter treble string because of the high A that I need to tune up to pitch. I’ve also incorporated complementary strings in various intervals from Ab to Ab where the pickguard would normally be.

“It’s what Pythagoras would build if he were alive,” deGruy laughs.

In addition, deGruy played Pierre Bensusan’s guitar festival in France, where he was featured along with Tommy Emmanuel. deGruy also modestly mentions a phone call from Steely Dan a few years back, expressing interest in auditioning him, but “…I just couldn’t go back to the six-string,” he said.

The Becker/Fagen connection is hardly superficial; Jay Graydon, who created the solo for Steely Dan’s hit “Peg,” is producing deGruy’s next album.

Other extraordinary names in deGruy’s life include Emily Remler and Larry Coryell. Both are now sadly gone, but Coryell, who loved unconventional talent, was enamored enough to hang out whenever possible and invite deGruy to sit in at a performance in Asheville.

When someone approaches deGruy to express awe in his ability, his stock response is, “Don’t confuse talent with someone who has a lot of time on his hands!” – Jim Carlton

This article originally appeared in VG‘s June 2018 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.