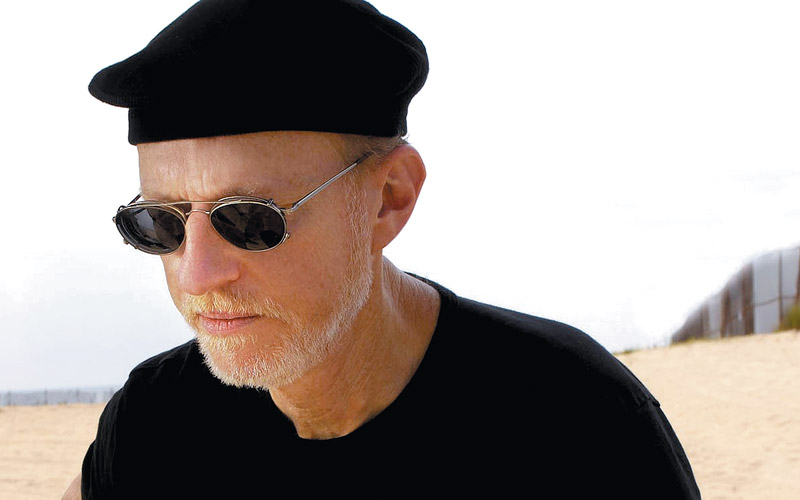

Although by most estimates he produced fewer than 100 Trainwreck amps, Ken Fischer – tech, designer, and amp-maker – will be remembered as one of the most authoritative and intuitive tube-amp gurus ever to have touched soldering iron to circuit. Born in Bayonne, New Jersey, in 1945, Fischer died at his home in Colonia on December 23. He was 61 and since 1988 had suffered from chronic fatigue immune dysfunction syndrome and related complications, and while his illness had prevented him from making his own amps or doing regular tech work since the late ’80s/early ’90s, he continued until his death to design circuits and contribute his knowledge to the tube-amp world at large.

Despite the enormity of his reputation in certain circles, Fischer was denied fame and recognition among the broader guitar community, and certainly would have achieved it if not for the impediment of his illness. His limited contact with guitarists beyond those on the Eastern seaboard whose amps he serviced in the early ’80s, and the major names and collectors who bought the amps he built in the years that followed, meant he remained a somewhat enigmatic figure to many. This image was in no way fostered by the reality of the kind, generous, and frequently jocular man his friends and acquaintances knew him to be.

Fischer’s formal training came in the form of electronics classes at a vocational high school, an RCA diploma course in electrical engineering, a tour of duty with the Navy as an aviation and anti-submarine technician, and employment as an assembler, technician and, ultimately, engineer with Ampeg in Linden, New Jersey, in the mid 1960s. After some years away from his vocation spent repairing motorcycles, Fischer returned to guitar amps in 1981 and founded Trainwreck Circuits. Initially an amp repair and modification business, he also built the first from-scratch Trainwreck amp in late 1982/early ’83 at a customer’s request. Through sheer word-of-mouth demand, he was soon forced to build more in his spare time as his amps began to be heard by a wider circle of musicians in New York and New Jersey. From there, Fischer’s tremendous talent elevated him to being recognized as one of the world’s top designers of high-end, hand-built tube amps.

In an effort to further define labels such as “amp guru” or “tube genius” or “master tech” that were frequently pinned on Fischer, it’s worth noting that his talent comprised a rare combination of intensely honed skills, the two principle components of which were in the very concrete realm of the engineer, and the far more esoteric realm of the auditory elitist. Fischer possessed an old-guard tube technician’s understanding of the minutia that contributes to a circuit’s function alongside a rock guitarist’s honed appreciation for the tube as a tone generator rather than just an “amplifier” in the literal sense. As tube amp tech, designer and builder, Fischer interpreted every conceivable fine-point to achieve his goal – from the matching of wire to application, to the type of metal that transformers and chassis were made from, to relative positioning of components and on, ad infinitum. As a listener, he strove to construct an instrument that would sing with rich harmonics and respond with unparalleled sensitivity to its player’s every touch and command, to create the euphonic tonal experience that can make an electric guitar performance transcendent.

While his illness kept him from any intensive work with his own hands in his later years, Fischer made major contributions to high-end guitar amp manufacturing by designing the Komet 60 model for Komet Amplifiers, by contributing his design for an output attenuator to Michael Zaite, of Dr. Z amps, to be manufactured under license as the Air Brake, and by designing an output transformer for Dr. Z’s Stang Ray amp, an EL84-based creation designed by Zaite to emulate the tones of country picker Brad Paisley’s beloved 1960 Vox AC30. Of Fischer’s death, Zaite said, “To my mentor, my inspiration, and my true friend: may your gentle spirit find eternal peace.”

Fischer is survived by his mother Esther, a sister, Mona, and a brother, Scott. His funeral was held December 28 at Beth Israel Cemetery in Woodbridge, New Jersey.

Thoughts From a Legend

(Ed Note: Ken Fischer was one of the most respected designers in the tube amp world. VG contributor/amplifier historian Dave Hunter spoke to him at length in February, 2005, for his book, The Guitar Amp Handbook (Backbeat Books) and this interview is excerpted from the tapes of that conversation).

Although he was clearly in pain at the time, Fischer was jovial, effusive, enthusiastic, and eager to share his knowledge. His designs live on in the form of the Komet 60 amplifier and the Trainwreck-licensed Dr. Z Air Brake attenuator, as well as the Fischer-designed output transformer used in the Dr. Z Stang Ray.

As reads the early history of so many great talents before they hit their creative stride, Fischer’s childhood and early adulthood sketch the story of rambling, dabbling, and experimentation. He tinkered with tube circuits as a kid growing up in New Jersey, picked up the electric guitar, got hooked on rock and roll and motorcycles, and studied some electronics in school. Later, Fischer took an RCA engineering course after leaving high school, then did a stint in the Navy as an aviation and anti-submarine technician. As a young man, he worked as a TV and radio repairman, bummed around on his motorcycle (where he earned the “Trainwreck” handle for his wild riding style), and eventually answered a want ad from a newspaper in New Jersey, where Ampeg was seeking assemblers. Although Fischer didn’t know it at the time, this was the fork in the road that would put him on the path to his true calling.

Dave Hunter: After a certain amount of training and a lot of self-teaching, you got your official start in the guitar amp world working for Ampeg in the mid 1960s.

Ken Fischer: Yeah. At first, I was on the final assembly line, and about the second week, a bunch of Gemini IIs were coming down… I said, “Hold it, man. These amps have got a mistake in them.” I went to the supervisor and told him they had a wrong-value resistor in there, and he said, “How would you know that?” I told him I could read the code and it’s wrong, so he should get an engineer out here. When the engineer came out, he said, “You can read the color codes?” So I told him about the RCA course, and he said, “That’s what the vice president of the company took. You know electronics – you’re a tech. Why are you working on the assembly line?” They had a tech leaving the final assembly room, where they check out the amps, so they moved me down there. And on my first day they had a pile of over 100 amps in the corner that needed fixing because they’d been getting backed up. They said, “You’re probably not going to keep up, so you’re just going to make the pile bigger, but if you eventually figure out how to work, you’ll be okay.”

Two weeks later, I’d not only fixed every amp in the place, but the 100-amp pile was gone. Their jaws just dropped.

So they recognized your abilities pretty quickly?

Well, Everette Hull, the president of Ampeg, recognized that I was pretty talented, and whenever one of his personal friends would come in – an artist or someone – he would have me work on their amp. Ampeg was always full of major artists, because don’t forget, we did all the jazz guys and the country guys – Ernest Tubb & The Texas Troubadours, Lionel Hampton, Dizzy Gillespie, all the guitarists; “The Tonight Show” was in New York, so we got Barney Kessel, Herb Ellis, Tony Mattola – we had guys like that in there day in, day out.

Everette Hull said to me, “When one of these guys comes in, you stick with him all day and make it right. Whatever it takes to get his amp right and make him happy, that’s what you do. Then at the end of the day when he says ‘How much?’ you tell him it’s on the house. And if he tries to give you a tip, don’t accept it.” He had this thing about quality and pleasing customers.

There’s a lot to be said for that.

Sure. That’s one of the ideas that he really impressed me strongly with. Some of his ideas were absolutely stupid. For example, when The Beatles and The Rolling Stones were out, he was saying things like, “Rock and roll doesn’t swing, it never will, it’s not musical, and we will not ever make anything for rock and roll.” And he was proud of saying that, because his guys were playing bebop, jazz… and Everette himself was an excellent musician. So I worked there for a couple of years and learned what the corporate structure was, and that was not so good. Then when they sold the company, the new owner was not a musician. The day the deal was signed, I quit. I was still into motorcycles, so I just rode and did bike repair for a number of years.

When did you get back into amps?

Well, the U.S. government put huge tariffs on imported motorcycles to try to save the U.S. motorcycle industry, urged by Harley-Davidson, so business slowed down a lot for me. I didn’t want to go back to dry cleaning, so I decided to repair amplifiers. I put a couple of ads in local newspapers, set myself up as a business, and in 1981 I officially became Trainwreck Circuits.

This was a tough area because there were a lot of famous shops where famous musicians would go when they’d play New York. Within one year, they were all complaining that I had stolen all their business. Because when I started Trainwreck I said, “There’s no bench charge. Come in and I’ll give you an estimate, and if you don’t like the estimate take the amp out. No problem.” Everybody else had a bench charge, besides anything else they’d do, as soon as you walk in the door. I got to the point where I had a separate guy whose job it was to take the chassis out of the cabinets. I’d fix the amps, and he’d put them back together, because my time was more valuable fixing the amps. I got this reputation that I could fix amps while guys waited, so I was getting amps from Boston down to North Carolina. Guys would make appointments, I’d say, “Come up here, I’ll fix the amp while you sit and wait,” and no other place would do that.

When did you build your first Trainwreck amp?

It was around 1982, and I was friends with a woman who was working directly under Ahmet Ertegun in New York, with Atlantic Records. They had an artist that they were recording, his name was Caspar McCloud, and he was one of the two original John Lennons in “Beatlemania” at the Winter Garden. Alternate shows were done by Marshall Crenshaw, and I worked on his amps, too. Marshall was down here several zillion times in the old days. So Caspar comes down here and says, “I just did an album for Atlantic and they bought me a Mesa Boogie.” I never had a problem with a Mesa Boogie amp, but it doesn’t sound like a Vox, which was what Caspar had been playing before. But one thing that Mesa had that Vox didn’t have was high gain. He liked that for the solos, but he didn’t like the master volume and he didn’t like the 6L6 sound – he liked EL84s. So I made a prototype from a stripped out old Super Reverb chassis I had, mounted some transformers, and put two EL84s in it. He came down, and I said, “The amp I’d make you would be twice as powerful, but this is the basic premise.” He loved it, so he said, “Make me the full-size one. By the way, what are you going to do with this one?” I said, “Oh, it’s just old junk parts, you can have it.”

So, in January, 1983, the first real Trainwreck – done from scratch on my own chassis – was Caspar’s Liverpool 30, Ginger, which is now owned by a guy who works in New York City as a detective.

But that was it – I made him the amp, and I wasn’t planning on making any more. I was making a lot more money repairing amps and selling tubes. And what can you sell them for? The first Trainwreck sold for $650 and took me several days to build, whereas I was making a $1,000 a day fixing amps.

But word got around…

Yeah. Caspar would play the amp in the studio, and guys would say, “Hey, what kind of amp is that?” Before you know it, they’d be saying, “I want one.” I told them they’d have to wait, because I had 50 Marshall heads stacked up awaiting repair, 20 AC30s… I started building more amps, but I always thought it was just a part-time thing. I brought the price up to $1,000. In 1984 I added a model called the Express. There was a guy I became friendly with, I was always servicing and modifying his Marshalls. He said, “I like EL34s, and I like the Liverpool sound. But can you do something a little more aggressive and crunchy?” So I made the first Express. Through the years, I’d raise the prices a little bit because the cost of parts would go up and so forth. So they’d be $1,200, then $1,600, then $1,800.

Then I decided I was going to make a series of amps kind of based on Vox amps, but not a clone, because I don’t do clones. I did the Rocket, but I got chronic fatigue immune dysfunction syndrome in 1988, so my health was terrible at this time. I was still doing repairs, but on the basis that I couldn’t promise it for any particular day, because I might spend a day in bed. I would always be going to doctors and they’d be diagnosing things. Then other things started happening with me – I got a GI bleed, I had a stroke, and whatever.

So I made one Rocket for myself, just as a prototype, then a friend played it and wanted one. I’d gotten four transformers when I ordered the prototype because I wanted to see how consistent they were, so I built a second one for him, then I ended up building a total of about 12 of them – I don’t really count because I give them names instead of serial numbers. If you give me the name of an amp, I can tell you what model it is, what it sounds like, everything. If you give me a serial number off an amp, that doesn’t mean anything. I used to put in my brochure, “You wouldn’t give your children serial numbers. Neither would I.”

So that’s what happened. But I eventually got so sick that I couldn’t do repairs any more, period. Although I do so for some famous rock stars, because I have an agreement that the guys bring them down here and get the parts for me, and I’m not going to box them or ship them. So I’ve been doing that for Mark Knopfler, and working with Metallica, and Aerosmith and Ritchie Sambora, because he’s a Jersey guy. Billy Gibbons was the first famous guy to buy a Trainwreck, back in the ’80s. It’s just easier for me to deal with guys like that because they appreciate [the circumstances], “Well, do it if you can do it…”

And they’ve got other amps to play meanwhile.

Yeah, they can get by. And they can afford to send a guy down with the amp, which most ordinary guys can’t do. So that’s basically what’s been happening.

I designed amps for these two guys down in Baton Rouge, Louisiana – the Komet 80 – which was a limited edition of 20 KT88-powered amps.

Any idea how many Trainwrecks you made over the years?

I don’t count them, because I think it’s a total jinx. I have a record book with every Trainwreck I ever made; the name of the amp, the year it was built, what kind of amp it was, what tubes it left with. And I could easily count them, but it’s not that many. If I was to guess, I’d say there were probably 100 Trainwrecks in the world.

What do you think about the fact that they have become such collector’s items?

That’s kinda’ nice, and bad at the same time. People say, “Hey Ken, you started the boutique thing.” I get that all the time, but I say, “No, I didn’t.” The guy I truly believed started the boutique amps in the modern sense was Howard Alexander Dumble. He had amps out way before me, and it seems his amps and my amps are the ones that are now the high end of that market. You know, a guy just paid $28,000 for an Express. Though if you’re lucky, you can still spot one for under $20,000. But that was kind of nice, although it never benefited me, because I never charged anything like that for an amp. If I sold an amp to a guy for $650 and he turned around and sold it for $20,000 that didn’t benefit me. Several years back I instituted a policy; any Trainwreck amp out there has a “Triple your money back” original purchase price guarantee. So if you’ve got a Trainwreck and you don’t want it any more, send it back to me and I’ll look up the original purchase price and refund it triple. Everybody cracks up at that, because I’m offering maybe $3,600 back for an amp that’s worth $20,000.

When people call me an “icon” and stuff, I hate that. The only term I will go with is “guru” because a guru is a teacher, and I like to share knowledge. So yeah, I will go with that.

Anyway, when the amps started going up, that was kinda’ cool at first. But now they’ve reached the point where a lot of real musicians can’t afford them, so the amps just sit around. When I made amps, I always thought of them as something to make music, to make the world better, make people happy.

That’s kind of sad.

Yeah. But that’s the way it is with vintage guitars or collectable amps. People are afraid to take it out. In that respect, I’ve actually sold amps and done things for people because I like [my work] to be out there making music. I had an amp in 1998 that I was selling, and one guy who was a great guitar player, I sold him that amp for $5,000 less than I could have got for it because he was going to play it out. The other guy was going to [take it] into the music room in his mansion. I’d rather lose the $5,000 and have the amp played out than have it sit in a room with one guy.

Are you still designing circuits?

Oh, sure. I’m designing amps all the time… Just little amps to play for myself, or amps I’ll end up giving away to friends or whatever. What I like about electronics and amp design is the innovation. I enjoy finding that little thing in a circuit that just makes the difference. When I went to school at RCA, the guy always told us to be creative, “Don’t just follow the book.” I guess, when you’re doing amps, there’s this thing that to me is like… there’s guys who can write songs, and there’s guys who can’t write songs; it’s the same with electronics. I come up with clever little ideas all the time, and I have a little log book where I log all these ideas. I have a little circuit where you can change the bias on a cathode-biased amp without changing the cathode resistor; I have over 100 master volumes for amps; all kinds of things. I like inventing stuff.

Do you think you’ll ever publish your own circuits?

I don’t know. I’ve got a lot of things that might help a lot of guys out, but at the same time I don’t like to reward amp builders who aren’t coming up with their own ideas, who just want to copy stuff. Guys will call and ask for stuff, and I’ll help them if I know what they’re going to do with them and they’ll respect what I give them. Like [Michael Zaite]; I’ve told him some of my ideas and he built things from circuits I’ve given him. Like a little amp I designed called a Dirty Little Monster, a single-ended amp, and Joe Walsh wanted a couple of these for recording. But when [Zaite] came out with his own single-ended amp, it was different, a single EL84 at four watts, so I know I can trust the guy and give him something, and he’s not just going to call it his own. He does very original designs himself, and that’s why we get along so well. And the other thing is, he’s actually an engineer. He knows what he’s doing.

“When people call me an ‘icon’ and stuff, I hate that. The only term I will go with is ‘guru’ because a guru is a teacher, and I like to share knowledge. So yeah, I will go with that.”

Final Stop for Trainwreck

Ken Fischer may be gone, but he hasn’t been forgotten. Over the past month, 70 of Ken’s fans, family, friends and the most talented amp builders on the planet joined forces to pay him homage by constructing the “Ken Fischer Memorial Amp.” A collective labor of love to create one last authentic Trainwreck Amplifier, and bid farewell to a man many consider one of the founding fathers of the boutique amp business.

Next month, we’ll get the whole story, as well as details on plans to auction the amp and donate the proceeds to Ken’s family.

This article originally appeared in VG’s April 2007 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Everybody goes to Rudy’s, but they don’t go to find the cheapest stuff or deal their way to the lowest

Everybody goes to Rudy’s, but they don’t go to find the cheapest stuff or deal their way to the lowest