There was a time in the mythic ’70s when guitarists were real men and lugged around 15-pound Morley Rotating Wah pedals to gigs and studios. And if they weren’t real men, they had roadies who were!

From the accelerator-like pedal to the chrome-plated chassis, Morley’s RWV and the firm’s other super-duty pedals were the American muscle cars of guitar effects. They were renowned for their sound and their reliability, and if they ever broke down, they’d have a solid second life as boat anchors.

The Morley wah was truly a better mousetrap. Thomas Organ Company had pioneered the wah pedal in ’67 with its Cry Baby and Vox Clyde McCoy models. But Morley did the wah one better. Then, the firm added other effects to the menu, including the flagship EVO wah with volume and echo, and the groovy RWV with volume, wah, and rotating Leslie-like sound.

These creations came from the mind of Raymond Lubow. The Bronx-born Lubow studied electronics at Manhattan’s Hebrew Tech before serving in the Army Signal Corps during World War II. Post-war, he settled in Los Angeles and opened a radio repair business, similar to a certain Mr. Fender down the road in Fullerton.

It was hardly a background that hinted at far-out contraptions, but in the mid ’60s, Lubow designed an electromechanical echo unit employing a rotating disc inside a metal drum filled with electrostatic “mystery” oil. With his brother, Marvin, counting the money, Lubow started Tel-Ray Electronics, the name derived from his shop that repaired televisions and radios. Tel-Ray’s Ad-n-Echo stand-alone unit allowed musicians to re-create echo effects without echo chambers or the famed Sun Studios dual-tape-machine setup. Sold as the Adineko, the compact component was included as an OEM part in amps and effects units from Rickenbacker, Fender, Gibson, Univox, Vox, and others.

Lubow developed his oil-can concept further to simulate the spinning-speaker sound of a Leslie speaker cabinet. The brothers took their Rotating Sound pedal to market as the Morley – offering “more-lee” than a “less-lee.” Get it?

Lubow’s oil-can technology was brilliant in its simplicity. He used the metal can as a rotating capacitor, driven by a small motor. A wire brush transferred the signal to the exterior of the drum, where another brush on the inside picked it up. The conductive oil served as a buffering layer inside the drum, and the delay time was determined by how fast the drum and its mysterious liquid was spinning.

The oil-can unit was housed on a solid, chrome-plated metal chassis with a rubber-covered treadle pedal. The Morley was near bullet-proof – truly a stompbox you could stomp on!

Thanks to that large chrome housing, Morleys also boasted a long pedal throw – much longer than the Cry Baby/Vox. This allowed for subtle and precise control of the volume and wah – even if you were wearing cowboy boots and bell bottoms.

The Lubows began mixing and matching components and soon had a full line of pedals. They added a volume control to the Adineko plus a wah effect, and soon had the EVO Echo Volume pedal. Substituting their Rotating Sound Synthesizer into the unit, in 1971/’72 they created the RWV Rotating Wah Volume pedal. Retail price was a steep $259.95.

Inside, the Morley was unique. The Cry Baby/Vox wah used a rack-and-pinion gear from the pedal to drive a potentiometer, a setup that became commonplace on the numerous copycats. The Morley, however, used an electro-optical circuit with the pedal operating a shutter that controlled the amount of light from a bulb that reached a Light Dependent Resistor (LDR).

The great advantage of the LDR circuit was doing away with that electromechanical potentiometer. Pots can load a guitar signal, which cuts into the treble sound; the Morley’s LDR retained the full spectrum of a player’s tone. And as pots get dirty over time, their sound gets scratchy – another thing omitted by the LDR circuit.

Still, that little light bulb was one of the few things that would stop working on a Morley. But come on, how many guitarists does it really take to change a light bulb? In addition, Morley pedals were not dependent on a 9-volt battery or wall-wart transformer; Lubow instead designed the effects to run on AC and wired them with a standard cord.

Morley pedals were big. Darn big. Place an RWV next to a Maestro Fuzz-Tone (reining fuzz driver of the day) and the RWV dwarfs the little fellow. It could even make your Marshall plexi stack feel, um, inadequate.

Throughout the bad ol’ ’70s, the range of Morley pedals kept growing, all with that chrome chassis; there was the WVO Wah Volume, VPFV Phaser Volume Wah, CFL Chorus Flanger, ECV Echo Chorus Vibrato, PFL Flanger, CO Volume Compressor, PWF Power Wah Fuzz, and more. All began life as the plain-old indestructible VOL Volume pedal.

To market their wares, the Lubow brothers hired political cartoonist Hank Hinton to draw the character of one of those real men – the wailing, long-haired ’70s rock guitarist who would soon be building his biceps by touting the Morley Rotating Wah to gigs. “The Morley Man” is still used in the company’s ads.

Plug a natural-finished ’70s Strat – an ideal guitar for the era – into an RWV, and you can began to play with combinations of the effect’s three features – the volume control, wah, and rotating-speaker simulator. But to truly appreciate the RWV, get all three going at once. Turn the Intensity knob, and that little oil can spins for all its worth. The Variation lever adjusts the tone from watery to drought. The sound is a swelling, whacked-out, dreamy voice that instantly turns you into that wailing, long-haired Morley Man. It’s a pure, anti-establishmentarianistic chromed tone.

You can receive more great articles like this in our twice-monthly e-mail newsletter, Vintage Guitar Overdrive, FREE from your friends at Vintage Guitar magazine. VG Overdrive also keeps you up-to-date on VG’s exclusive product giveaways! CLICK HERE to receive the FREE Vintage Guitar Overdrive.

This article originally appeared in Vintage Guitar magazine January 2013 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

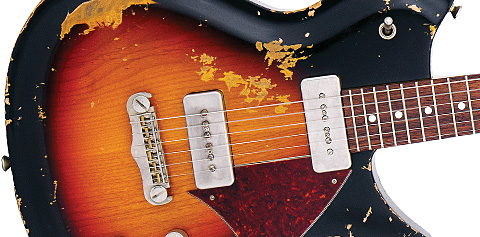

Introduced in the late 1950s as Fender’s “jazz guitar,” the Jazzmaster was also supposed to compete in the market with Gibson’s semi-hollow ES line. But despite its very specific moniker, the guitar never caught on with the jazz crowd.

Introduced in the late 1950s as Fender’s “jazz guitar,” the Jazzmaster was also supposed to compete in the market with Gibson’s semi-hollow ES line. But despite its very specific moniker, the guitar never caught on with the jazz crowd.

Renowned folk singer/songwriter, musicologist, organizer, and political activist Pete Seeger died January 27 at a hospital in New York City. He was 94 and passed from natural causes.

Renowned folk singer/songwriter, musicologist, organizer, and political activist Pete Seeger died January 27 at a hospital in New York City. He was 94 and passed from natural causes.