There once was a time when pointy headstocks, locking vibratos, and refrigerator-sized effects racks were the norm. Fast players with flashy gadgets ruled the world – until, that is, an unassuming young rocker appeared on the scene to shake things upside down and bring back the basics.

That player was Slash – lead guitarist with a band called Guns N’ Roses. Armed with a simple setup that included a Les Paul Standard and 100-watt Marshall, he made his mark by showing players that all you need to achieve greatness are a true sense of melody, good tone, driving ambition, and an attitude that separates you from the masses.

Once Guns hit, players began to follow suit by taking the minimalist approach favored by Slash. They also started buying Les Pauls, which had become the hard-sell instruments of the era, and returning to a basic guitar/amp setup. Both Gibson and Marshall recognized Slash’s influence and honored him with signature models.

Fast forward. After spending most of the ’90s in low-profile style, in 2003, Slash returned with a new band called Velvet Revolver, which arrived just in time to rescue radio from an overflow of bands with no substance and soul, and bringing back the true spirit of American rock and roll.

Vintage Guitar was recently invited to indulge its voyeuristic fetishes with a visit inside Slash’s guitar vault, a collection assembled over years and including some of the finest examples of Gibson and various other cool instruments. Slash proudly showed us his personal favorites, then discussed Velvet Revolver and how its first album came together.

Vintage Guitar: You have an amazing guitar collection. Do you have any favorites?

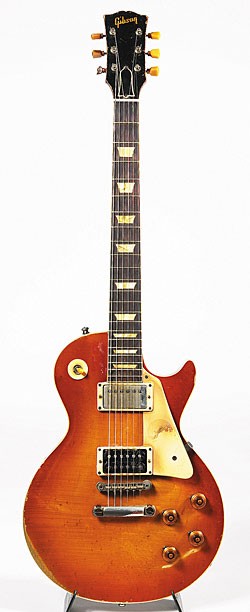

Slash: I’m really attached to my guitars. Everything I have in some way, shape, or form is a favorite. I’m partial to Les Pauls, of course. A couple of them are replicas, and one is very dear to me because it’s the guitar that really cut the ties between me and any other sort of guitars. It was built by Kris Derrig, and I got it through Guns N’ Roses’ management when we were doing basic tracks for Appetite For Destruction. I was experimenting with guitars, but didn’t have any money so I couldn’t just go pick up anything I wanted. Being in the studio for the first time, I realized that I had to get a guitar that really sounded good. I’d been using Les Pauls, but they’d get stolen or I’d hock them. So Alan Niven, the band’s original manager, gave me this hand-made ’59 Les Paul Standard replica. I took it in the studio with a rented Marshall, and it sounded great! And I’ve never really used another. It has zebra-striped Seymour Duncan Alnico II pickups.

The very first electric guitar I ever had was a Memphis Les Paul copy. I didn’t know much about guitars, or that different guitars sounded like. But I was drawn to Les Pauls. As I got older, the Memphis gave up the ghost. From there, I ended up with a B.C. Rich Mockingbird. I worked in a music store, so I had a chance to get a Strat, then I went through a couple of other Les Paul copies. When Guns N’ Roses started, I was getting a better idea of what different guitar players sounded like and what they used. I picked up one of Steve Hunter’s Les Pauls at one point, and later hocked it. I also hocked my Mockingbird during the more chemical-dependent days of my youth. Then I went through various Jacksons and would try anything Albert at Guitars R Us would loan me.

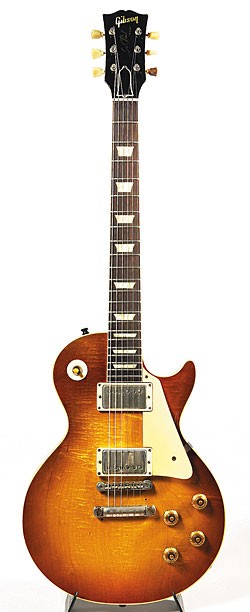

I ended up in the studio with the Les Paul replica, and that was my main guitar through the beginning of the first Guns N’ Roses tour. I later got another replica made by someone named Max. I had those two on the road for the first year. Then, when Gibson gave me a deal on two Les Paul Standards, I put the away replicas because I’d banged the crap out of them. And I pretty much used the Gibsons throughout Guns N’ Roses, Snakepit, and Slash’s Blues Ball bands. Now they’re very roadworn, so I put them away, because they’re really good guitars. After that, I started to use newer ones, including my signature models.

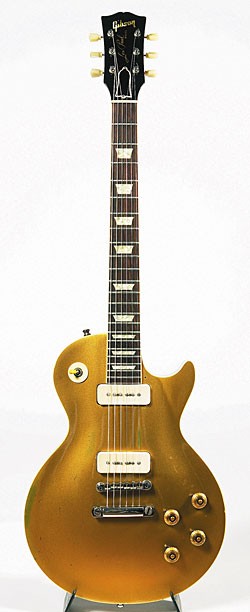

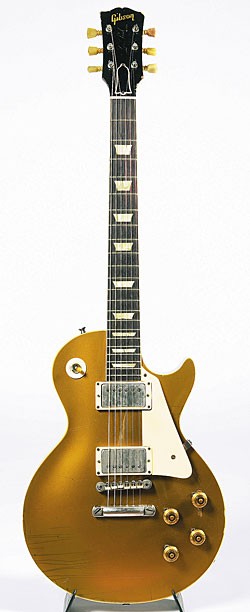

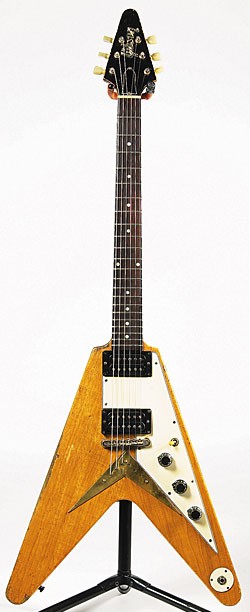

Over the years I’ve picked up instruments that I’d pay huge sums of money for and are very special to me; the original Les Paul Standards from ’59 and ’58; the goldtops – a ’58, a ’57, and a ’56 with P-90s; the doubleneck is a ’67 EDS-1275 that I found at Guitars R Us. It was already refinished in black, but I got it when I was buying guitars for particular songs. That one was the “Knocking On Heaven’s Door” guitar, and I had it on the road just for that one song on the Use Your Illusion tours in the ’90s. Then there’s the ’58 Flying V and ’59 Explorer, which were just things I had to have. The Explorer and the V were never taken on the road, but the goldtops influenced me to get a reissue from the Gibson Custom Shop – a 1960 Classic that sounded amazing. It was stolen from me. I got another once since, but it’s a different model. I like Les Paul Juniors, too, and have a few of them. I’ll write a certain song, and know when that’s the kind of guitar sound I need, so I want to have one close by.

I’ve never taken any of the real old guitars on the road because I’m reckless when I play. You won’t see me toss a really good guitar or do something real dramatic, but I’ve broken a lot of stuff onstage, so I need something that doesn’t have much sentimental value. I do get attached to a new guitar if I’ve learned how to make it do what I need. Then I’ll keep it out for as long as I can, then if it really becomes my baby, I’ll put it away and get another one for the next tour.

But I haven’t been buying old guitars for a long time. I break them out when I’m doing sessions.

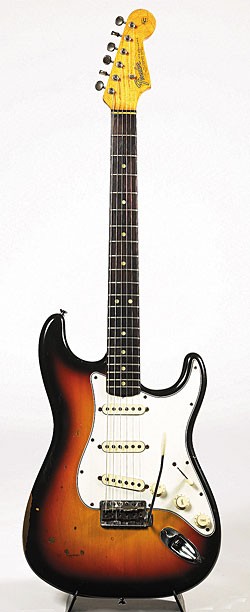

Les Paul replica built by Kris Derrig.

Do you recall the story behind your Firebird?

I picked up the Firebird from Guitars R Us, which was my main guitar source for a long time. I went down to do a video for something in a guitar store, and saw it on the wall. I’ve always loved Firebirds. They’re great, but I’ve never been able to find something to apply it to, except in Slash’s Blues Ball. Still, I had to get it! I just love the way they look, and they’re great for slide and for a Johnny Winter kind of sound – that sort of nasally pseudo-Strat tone.

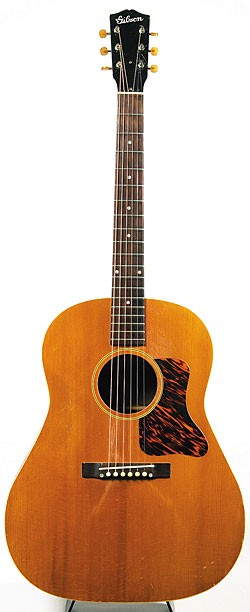

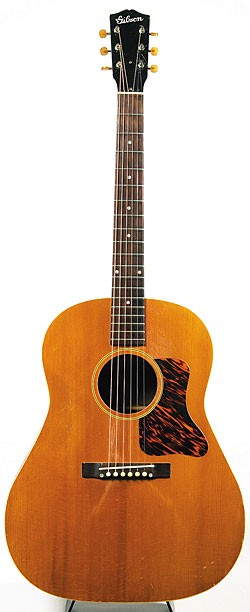

You also have some older acoustics.

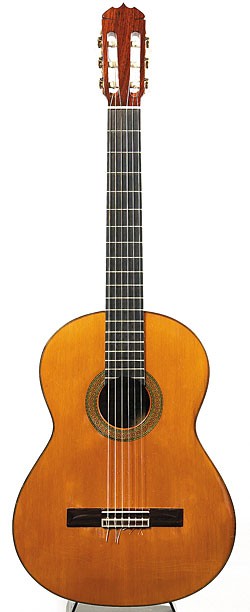

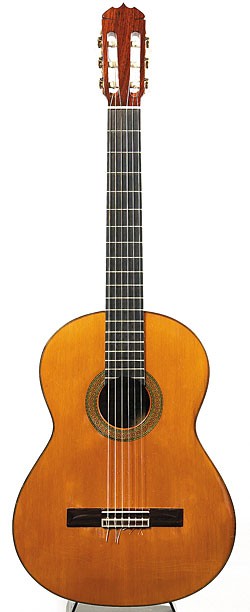

They’re two old Martins and a Ramirez classical that I picked up. I’m partial to acoustic guitars. Since I was a kid, I wanted to graduate to a Martin. So when I got a chance to pick up a couple, I did. Same with the Ramirez.

Have they been used on any recordings?

Yes. I’ve used a lot of acoustics. I used the Martins the most during the Use Your Illusion recordings. There’s a song called “Double Talkin’ Jive,” with an outro that fades into the electric part of the song, and it’s all a Flamenco-style thing. That’s what I bought the Ramirez for. I figured if I was going to have a nylon-string, I was going to have a great one. I really haven’t bought any since because that one is so perfect. I’m not sure how old it is. I also used it on a sort of “pseudo hit” that is all instrumental Spanish guitar. If you listen to adult contemporary radio, right next to Kenny G, there I am, and you’d never know! It’s called “Obsession Confession,” and it was for a soundtrack for a Quentin Tarantino-produced movie called Curdled. I hear it all the time in malls. What scared me is that my mom called me one day and said that she was sitting in the bathtub – already too much information (laughs) and heard this music, and that at the end the DJ said it was Slash. She told me what it was, and it’s been sort of a standard on adult contemporary radio ever since.

Was it odd to hear your music back-to-back with Kenny G!

I actually did a gig at UCLA – some jazz festival – and Kenny G played, as well. It was a strange kind of surroundings for me! But over the years, I’ve managed to fit into all kinds of niches. I think it’s a good thing to do because it keeps you humble and keeps your chops up, and if it’s something that you actually like and don’t play all the time, it’s good to test your skills. The very first guitar I ever had was a beat-up old Spanish guitar my grandmother gave me. It had one string on it, and I learned about half the cover songs I know today on that one string! I was learning to play Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin on a Spanish guitar! I finally graduated to six strings, on a guitar I carried around for a year. So I’ve have a thing for Spanish guitar, even if I do use a pick. I just like the feel of it.

With different types of guitars, do you notice any change in your style or approach to playing?

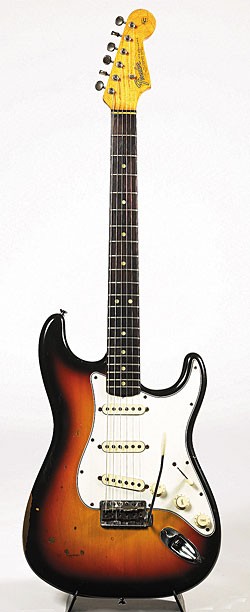

Yes. One of the reasons the Les Paul is such a mainstay for me is because once I got that sound and feel down, it gave me license to do what I wanted. But if I pick up a Strat, I play completely different. I actually think that the Strat – hands down – is probably the best rock and roll guitar, but they’re really not for me because they’re just too unpredictable and too light. I will use one every so often if I want something that just really screams, but I have to go through a dozen to find the right one. I’m not as “chameleon-like” on any guitar – like if Jeff Beck were to pick something up and play, regardless of what kind of guitar it is, he sounds like Beck. But if you give me the wrong guitar to play a certain kind of song, it’s not going to work.

Does playing with different musicians also affect your approach to the instrument?

Definitely! That’s a big factor because I play a lot. Again, it’s very humbling to play with musicians outside of your usual genre, because you have to listen, and get away from what’s familiar, and then be open-minded enough to understand where they’re coming from. But the more you do that and the broader the span of musical styles you can adapt to, the more you grow as a musician and learn to play with other people by picking up on those nuances. It’s not something you can easily drink in. Playing with Ray Charles was one of the major events for me, where I had to play with a master, and pick it up right away.

Are you ever intimidated in those situations?

I’m always intimidated! In a way, I’m pretty shy about that kind of stuff. That’s probably why I make myself just get into it, put the blinders on, and go for it. It does intimidate me, but not to the point where I can’t perform.

When you’re playing with a “legend,” live or in the studio, do you feel more pressure?

It’s easier in the studio because you have more time. A good example is the Ray Charles thing. We did some stuff for the movie about him, and I was given chord charts… but I don’t read music! I’ve sat in with Les Paul and Blue Lou enough times, and I watch Lou’s fingerings and how he moves up and down the neck, but it’s something I’ve just never really been able to grasp.

Going into the studio with Ray was one of those things where the beats and chords changes were pretty rapid. I asked to go home and sit with the music for a bit, sat up all night and learned it, then came back and recorded it the next day. It was pretty hard. But it would have been twice as hard to spontaneously do it live. A lot of times, when you jam live, there is no rehearsal. So I’d still say being able to adapt at the moment, to get up there and play something like that, is more stressful than having a chance to have one, two, or three takes in the studio.

Several members of Velvet Revolver were also in Guns N’ Roses. How do things compare?

I hadn’t played with [Guns bassist] Duff [McKagan] in about seven years. We got together on some of [former Guns N’ Roses guitarist] Izzy’s [Stradlin] stuff here and there, but hadn’t really played together in a long time. During those years, I’d been playing and really had been through a lot. I’d grown as a person, but probably even more as a musician. Duff was doing what he was doing, and [drummer] Matt [Sorum] was always playing previously-recorded material. He recorded the Use Your Illusion records with us, but we had already written the songs before he joined. So this was the first time I’d written material with him. It was also the first time in seven years that Duff and I played together on new songs.

So it was new for all of us because of all that had gone on in that seven-year period. It was exciting. Then Dave Kushner brought a kind of technophonic guitar style to the table, which I wasn’t too familiar with. I’d heard it, but he has a very original way of doing it that just fit well with my old-school rock playing, so that was great. Then [vocalist] Scott [Weiland] came in and gave it a voice which just turned everything into something really interesting. We auditioned so many singers before Scott came around, and I’d heard songs go in a lot of directions. Scott gave it a life that fit perfectly.

We went into the studio and made a record of some of the stuff that we’d written before Scott joined, as well as some of the stuff we’d written with Scott. We threw it all together, banged it out, and we were on the road before the album even came out! We’re still touring, and I’m working on material for the next one. I keep a little digital recorder with me, and record stuff in hotel rooms and during breaks. I put ideas down as they come to mind. After the next leg is over, we’re going to start pre-production.

Was there a lot of material that didn’t make it onto this first Velvet Revolver record?

We wrote lots of music, and we recorded everything. Then we gave bits and pieces of it to Scott. Most of the first stuff, he just went for. We also wrote a lot of new material with Scott. Then, out of 60-some songs we’d come up with, we picked 12. It was easy because we pretty much used the first stuff Scott went for. “Slither” was one of those songs. “Fall To Pieces” was something written before Duff, Matt, and I started. I was in the process of putting together another pseudo solo thing when this band popped up. So I had material that I’d recently written, and “Fall To Pieces” was one of those songs. All the stuff that didn’t get used could be for the next record. But at the same time, I hate going backward, and everybody’s writing new stuff. So we’ll see what happens.

You’ve always favored the Les Paul/Marshall combination, but have you added anything to the mix?

Marshall built me an amp (Marshall’s first-ever signature model) based on the Jubilee series that I’d always used. And I’ve been using that pretty much all the time. But doing the Velvet Revolver record, I expanded a little bit. I started using some old Fender combos like a tweed Champ and silverface Twin. I used different Marshall heads, too – anything that was around the studio – and tried to do things differently every so often because I didn’t want everything to sound the same. I experimented to see what kinds of applications there were for different amps, doing things like mixing a Marshall with a reissue Vox AC30 I picked up at Guitar Center. But there was nothing really out of left field, except a few different amps and some really old funky pedals.

What were some of those old pedals?

I have no idea! I borrowed alot of different things. I had some old harmonizers and octave dividers that had a little distortion in them because they were so messed up. There was an old distortion/wah pedal from around 1971 that one of the engineers had, and it sounded amazing. Sometimes I’d pick up something that just sounded really cool and try to find something to apply it to. So I’m not as stuck in a one-dimensional kind of thing as I embark on this next leg of my career.

When you started recording, were you using your standard setup or did you randomly plug things in as you discovered different gear?

Well, it started out pretty standard, with everything set up the way I normally do it. From there, I started experimenting. I would take the first song we’d record, and it would probably be the most simple song and need the least amount of scrutiny, and then used my imagination. So I’m looking forward to going into the studio and doing this next record because I’m going to get a chance to experiment with the ideas that have been brewing in my head for while we’ve been on the road over the last 15 months.

Did you use a variety of guitars for different sounds?

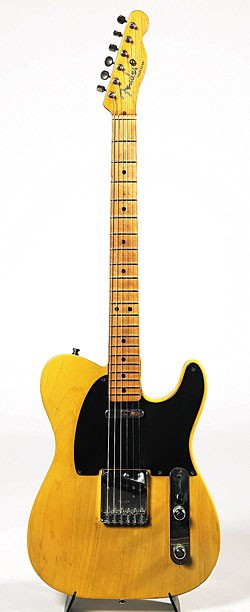

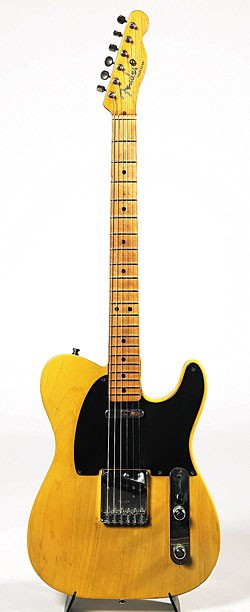

Yes. A good example is the first song on the record, “Sucker Train Blues.” I used a six-string bass, a Telecaster, and a Strat, which is pretty much unheard of, for me. I don’t know where that came from, but it worked out great. And there’s a song recorded for The Fantastic Four soundtrack, and I used a Fender Mustang as well as a Les Paul. It was a real quick recording – one night for the whole song. That was something that I’d heard in my head first. If there’s a musical idea or a riff of some sort, I already know in my head how I want it to sound, so I’ll grab whatever guitar I think is going to get that sound, and if it doesn’t work I’ll try something else and start the process of elimination until I find it.

Was there one particular guitar that you favored throughout the recording?

I follow the old adage, “If it isn’t broke, don’t fix it.” So when I go into the studio, the Les Paul replica I used on Appetite For Destruction has always been my main guitar. It will always be there. I got another one recently made by Kris Derrig that sounds great, and it comes with, too. Then I start breaking out whatever I need, based on the ideas I have. But when I go in to do pre-production, I’ll just take one guitar – the first ’59 Les Paul replica by Kris. I record all the basic tracks with that guitar, then go back and re-do some parts, trying different stuff.

Why do your vintage guitars often take a back seat to the newer ones?

I’ve found that I can usually make a guitar work, no matter when it was made. I use so many new Gibsons and other instruments, and I’ve just learned to adapt to them. You just have to break them in. The thing about vintage guitars is I’m not a collector for a collector’s sake, although I think guitars are probably some of the sexiest things in the world and I love having one close by. The vintage ones obviously have a certain kind of allure to them. But my whole reason for getting into vintage guitars was that I would hear them and they would have a certain kind of feel and tone, especially with the old PAFs. That’s why I’ve only collected so many, and they all have a certain tone and personality. You can draw on that when you want to hear something for a particular song. I truly love and respect old guitars, but I need to use what works best in each situation, and it really doesn’t matter whether it’s old or new.

Are your vintage instruments stock, or at least the same way you purchased them?

Yes. I haven’t messed with any because I don’t take them on the road. There’s no reason to screw them up. You fix certain things, like yesterday I broke a tuning peg on the ’58 Les Paul Standard, and I’m going to have to fix it. I have huge appreciation for old stuff, but if I can’t use it, I don’t need it around, and I don’t use the stuff often enough as it is. I only use it in the studio, for its personality. Plus, it’s such a liability these days, and I would never leave the old stuff in my house again. I keep everything pretty secure. If I saw a guitar I wanted, and it was worth it and sounded amazing, I might consider it. I borrowed a ’59 Les Paul Standard from Dave Wiederman a few weeks ago that had Les Paul’s signature on the body. I wanted so much to keep it because I haven’t bought any old guitars in such a long time. But once it was out of sight, it was out of mind. When you’ve got a bunch of guitars like that, there’s a feeling of not wanting anything to happen to them, so you treat them like pieces of porcelain. But at the same time all I have to do is hear something that sounds right and, like I said, it doesn’t matter whether it’s old or new. But there’s nothing like the look of a good-condition ’59!

Do you have a favorite guitar for writing?

I’ve got one on the road I write with, and I carry it on the bus. It’s a Les Paul Standard, a 2000-something model. I have another Standard from the ’90s that I write with at home. You can’t go wrong with Standards. Then I’ve got a newer small-bodied Gibson acoustic I use around the house. I recently got a Gibson jumbo acoustic with a maple body that I use to write with on the road.

Which guitars are with you onstage?

I think there are about 16. I’ve got a backup for every guitar. I have a few different Les Pauls – my regular Standard, a goldtop, and a black Standard with a Bigsby. I also have a couple of B.C. Rich Mockingbirds and a B.C. Rich Bich 10 that I use as a six-string. There are a pair of Guild doublenecks I designed with Guild a while back. It’s acoustic on the top and electric on the bottom, and a red Gibson EDS-1275. Everything is fairly new. I think the red Mockingbird is the oldest one I take out. I bought that from some guy on the street – literally on the sidewalk. I was at a club and he told me about it, and I bought it from him. I use it is primarily for the vibrato because I won’t take a Strat on the road. The tremolo on the Mockingbird is a Floyd Rose. All things considered, me and the Mockingbird go back and forth, but I use it for “Sucker Train Blues.” I use the Bich for Stone Temple Pilots songs.

How are your guitars set up?

I use an .011-.048 custom Ernie Ball set for the electrics, and for the acoustics, a .013 set. The action isn’t too high or too low, and I like a lot of tension. I play really hard and intonation is a big deal with me. But if I’m not careful, I’ll bend the strings too far, so I like everything to be very tight. I also use 1.14 mm Dunlop Tortex picks.

Describe your live rig.

I use four Slash signature model Marshalls, two for my dirty sound and two for my clean sound, with one cabinet for each head. I haven’t really expanded it for years. I use a Boss EQ to kick solos up a notch, a Dunlop Crybaby wah, and a Boss octave pedal, which I sometimes use with the wah pedal. I’ve also got a Dean Markley voice box, Yamaha SPX90 for chorus, the same Boss digital delay pedal I’ve had for years, and a Nady wireless.

The only thing I’m waiting on is a new Crybaby wah pedal that Dunlop made me that I’d used in the studio. It’s candy apple red with adjustable distortion and adjustable wah. It sounds amazing! It’s going to be a signature pedal and will be added to my live rig. There might be other stuff after the next record, but I’m still really a straight-up Les Paul/Marshall kind of guy. The Slash model Les Pauls have piezo saddles, though lately I’ve been using the Guild doubleneck for acoustic sounds. I just switch to the clean rig for the acoustic tones, and we put the guitar through a DI, as well.

What do you listen to for inspiration and enjoyment?

Well, I’m always looking around. My tastes haven’t changed much over the years, but they’ve grown a bit. I’ve started to like stuff that I might not have liked a few years back. It could be anything from pop songs that have a nice hook. But there’s nothing in particular. I don’t own any records – I just hear songs on the radio. I like some old-school hip-hop stuff that my wife has turned me on to, but I don’t like any of the commercial crap that’s out now. From the mid ’90s until now, I haven’t heard anything I’m really into. I still prefer the stuff I’ve listened to since I was a kid and started playing guitar – when I made rock and roll my own, as opposed to what my parents listened to. It’s the combination of all that music, like the Stones and Otis Redding, to the Who, Aerosmith, Bob Dylan, and Phoebe Snow. I was raised on the Who, Zeppelin, the Beatles, the Kinks, Yardbirds, Moody Blues – that was like my dad’s trip.

On the flipside of my family, I was raised on Marvin Gaye, the Pointer Sisters, Sly & the Family Stone, and this other blues and R&B stuff. I hated Elvis until I was about 30 years old, then I started to appreciate him.

So I’ve always listened to a lot of old stuff, but in the ’90s there was that a short period where a lot of great bands came out, and I still think those are some great records – Rage Against The Machine, Soundgarden, Nirvana, Stone Temple Pilots, Faith No More. Since then, there are very few records I really enjoy. The Foo Fighters are really good and the new record is very cool. I listen to a lot of stuff, but find myself getting bored. I’ve satellite radio in my car, and a lot of times I find myself switching between it and FM, trying to find something cool. Every so often, I’ll pick up a new CD. I picked up Joe Perry’s new CD the other day. It’s different than what I’d expect, but there’s some great playing on it. There’s a lot of music that I like, but I’m still looking for stuff that punches you in the stomach and is actually musical – and has some soul. It’s kind of hard to find.

I think a lot of people who share your feelings about music are picking up on Velvet Revolver and finding this record refreshing.

I can’t wait to get the new record out! The first one was the tip of the iceberg, and we managed to get some cool stuff on there with interesting ideas and great sounds. But it was really just like that first stab at making something exciting happen. We’ve done so much since then, and we’ve grown so much over the last 15 months as a band. We haven’t even tapped the surface, so I’m really excited about the next album!

This interview is dedicated to the memory of Marshmallow.

All Photos: Rick Gould

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Nov. ’05 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Besides fronting his own band, Verheyen also is a member of Supertramp, a gig he started in the ’80s. That one, he says, happens once or twice a decade, so it gives him plenty of time for his other musical endeavors.

Besides fronting his own band, Verheyen also is a member of Supertramp, a gig he started in the ’80s. That one, he says, happens once or twice a decade, so it gives him plenty of time for his other musical endeavors. His main live axe is a Seafoam Green Fender Stratocaster with a rosewood neck. He also has a ’58 sunburst Strat. “I feel really comfortable on the Stratocaster. More so than any other instrument. I can do more on that guitar than anything else.” That said, the “Frank Sinatra” in the studio can be pretty much any guitar, and Verheyen finds himself recording many solos with a Gibson. He uses a 335, a Les Paul, and at times, a Flying V.

His main live axe is a Seafoam Green Fender Stratocaster with a rosewood neck. He also has a ’58 sunburst Strat. “I feel really comfortable on the Stratocaster. More so than any other instrument. I can do more on that guitar than anything else.” That said, the “Frank Sinatra” in the studio can be pretty much any guitar, and Verheyen finds himself recording many solos with a Gibson. He uses a 335, a Les Paul, and at times, a Flying V.