-

Wolf Marshall

Pat Martino

Redefined Jazzman

Pat Martino is a legend. He has been delighting the globe’s collective ear for more than 50 years, making an undeniable impact on guitarists across the spectrum; Pete Townshend, Carlos Santana and Jerry Garcia are among his fans, along with (predictably) countless jazz performers. His credits read like a who’s who, and he has innovated

-

Wolf Marshall

Fretprints: Tony Rice

Newgrass Fusion Master

The world lost one of its most innovative and defining guitar voices on December 25, 2020. Bluegrass maestro Tony Rice – singer, composer, supremely accomplished sideman, solo artist, and flatpicking virtuoso – personified the evolution of an American folk form and its cross-pollination with jazz, classical, and pop tangents. With Rice’s imaginative vision and prodigious

-

Wolf Marshall

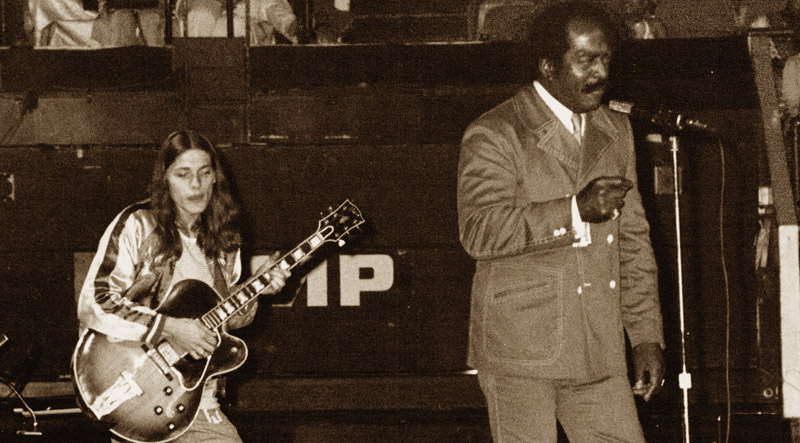

Fretprints: Robben Ford

The Early Years: Emergence of a Blues/Jazz Virtuoso

“Who is this kid?” gasped incredulous attendees of the Guitar Explosion festival at the Hollywood Bowl in June, 1973. It was a typical summer day, but the concert was anything but; an expectant audience there to see Roy Buchanan, T-Bone Walker, Shuggie Otis, Kenny Burrell, Joe Pass, Herb Ellis, Mary Osborne, and Jim Hall was

-

Wolf Marshall

Wes Montgomery: His Life and His Music

Oliver Dunskus

You don’t have to be a bebopper thumbing a Gibson L-5 to appreciate the music of Wes Montgomery – arguably the greatest jazz guitarist of all time. While his fan base includes Carlos Santana, Eric Johnson, Pat Martino, George Benson, and Pat Metheny, precious little has been written about his history and artistry. Oliver Dunskus’

-

Wolf Marshall

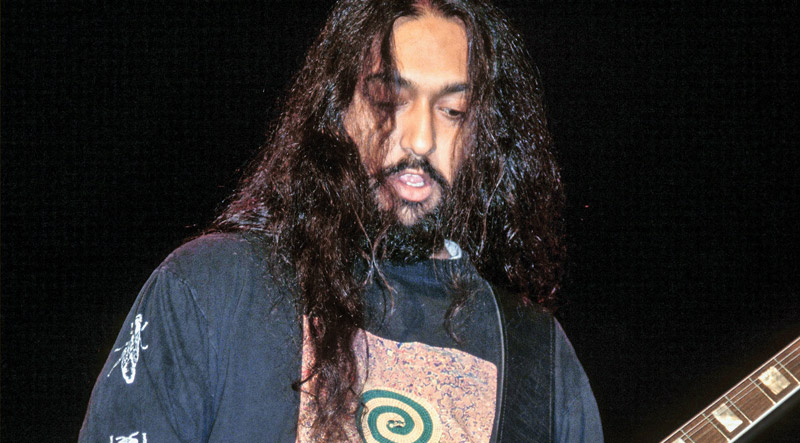

Fretprints: Kim Thayil

The Grungy Flowering of Soundgarden

In 1991, a movement emerged from Seattle that shook the musical world to its core. Seemingly overnight, a cadre of unlikely “grunge” bands from the Northwest rose quickly to attain musical dominance, sweeping aside the shred, glam, and prog-rock excesses of the ’80s. As the movement took hold, an alternative-rock attitude defined a generation of

-

Wolf Marshall

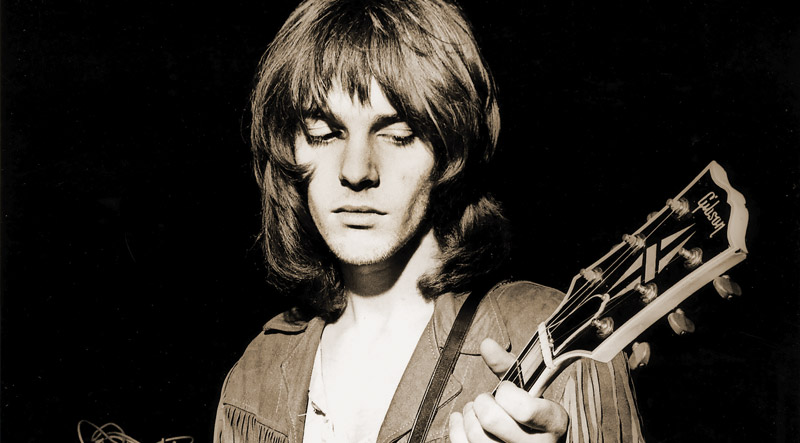

Peter Frampton

Part One: The Humble Pie Years

Formed with two formidable front men in Steve Marriott and Peter Frampton, Humble Pie was one of the earliest “supergroups” to emerge from the British Invasion and embody aspirations beyond pop. Marriott rocked audiences as vocalist of Small Faces, which scored hit singles with “Itchycoo Park,” “All or Nothing,” “Tin Soldier” and “Lazy Sunday.” Frampton

-

Wolf Marshall

Jimmy Bryant

Country-Jazz Virtuoso

When Leo Fender strode into a cowboy bar on the outskirts of Hollywood one day in 1950, he had no idea the contraption he was toting would become a central force in a new age of music. The Riverside Rancho offered an inviting atmosphere enjoyed by locals but was hardly the venue for myth making.

-

Wolf Marshall

Jerry Miller

Back to Basics

Jerry Miller is back. For many he never left – especially admirers of his innovative playing with the legendary Moby Grape. Clapton, Page, and Stills are on that list, as well as dozens of guitar heroes. Miller reached out to VG to share a preview of his newest recording venture, which finds him moving in

-

Wolf Marshall

Kenny Burrell

Playing It, Meaning It, Living It

Few can claim the title of living legend. Kenny Burrell is just such a person. In fact he’s more – he’s living history, past, present and future. His credentials are voluminous and accomplishments staggering, and he hasn’t stopped. He has recorded at least 108 albums as a band leader and is today, at age 82,

-

Wolf Marshall

Carl Verheyen

The Tools of Trading 8s

Carl Verheyen is a member of that elite (and shrinking) group of musicians known as “session guitarists.” Super-qualified pickers, they’re the hired guns brought in for the most demanding and important recording dates. They command triple-scale fees, but work in a pressure cooker where time is money, where skillsets call for expertise in blues, jazz,