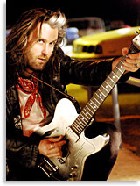

C.C. Adcock hunches over his Telecaster like a tiger ready to pounce. He stands on one foot, the other leg twisting like an unmanned fire hose – one leg wrapping and unwrapping around the other uncontrollably, while he precariously keeps his balance. He stands on tiptoes and backpedals as if it will help him reach a bend on his B string. He runs forward a few steps, thinks better of it, stops, and jumps straight into the air like a scared cat – his guitar squalling and shrieking accordingly.

And this is in the recording studio. Doing an overdub. On somebody else’s album.

Louisiana’s Charles “C.C.” Adcock is the musical/cultural equivalent of blackened redfish: a well-to-do white boy rolled in spices, dipped in grease, then fried. His it-ain’t-the-heat-it’s-the-humidity “swamp rock” occupies the space where R.L. Burnside and Doug Kershaw meet at the crossroads and sell their collective soul to Keith Richards.

Ten years ago, the singer/guitarist/songwriter released a self-titled debut on Island Records that charted the past, present, and future of Louisiana music. Already a veteran sideman to Buckwheat Zydeco and Bo Diddley, Adcock revealed a style that was authentic and imaginative, and seemed remarkably formed for someone in his mid 20s.

After producing two CDs by Cajun accordion master Steve Riley and one by the swamp pop super group Li’l Band Of Gold (which includes Adcock, Riley, and singer/drummer Warren Storm), Adcock recently released his solo followup, Lafayette Marquis on Yep Roc. Alongside collaborations with Mike Napolitano, Doyle Bramhall II, Mike Elizondo, and Tarka Cordell, who produced C.C.’s first effort, the envelope-pushing set includes one track produced by the late Jack Nitzsche, from what turned out to be the Oscar-winning producer’s last project. On that cut, “Stealin’ All Day,” Nitzsche, Phil Spector’s former arranger and right-hand man, turns the trio of Adcock, bassist Jason Burns, and drummer Chris Hunter into a bigger wall of sound than Spector could ever dream of.

Why the 10-year gap between CDs?

“Have you heard what’s been going on in the past 10 years?” the guitarist asks. “It wasn’t exactly a party I wanted to go to. When I heard Nirvana, I thought, ‘It’s not my thing, but it’s cool; everything’s getting ready to open up wide.’ A couple of months later, I heard Pearl Jam, and I pretty much knew we were going to be in for at least 10 years of locust plague – getting really bad. Not only did I not care to have any of those flavors in me, even a lot of the roots cats that we dig got so mediocre and forgettable. It got to the point where I couldn’t even listen to my favorite blues records, because they reminded me of somebody I’d seen recently just dumbing it down. But I was making music the whole time, working with different people and learning a lot, especially from Jack Nitzsche, and this record is an amalgamation of all that.”

Nitzsche was the second legendary producer Adcock had an association with, the first being the late Denny Cordell, whose credits include Joe Cocker, Moody Blues, and Leon Russell. “Denny gave me my first big break, vis-à-vis his son, Tarka. Thanks to his dad, Tarka had grown up with all these great rock and roll and blues records, and he had a real good understanding of American music – especially the Southern variety, including my hometown. He looked me up when he was in New Orleans, and I showed him some stuff I’d been working on, and he took it back to show his dad – who turned out to be Denny Cordell. Denny was actually one of the last of that old school, before A&R guys were just over-promoted Tower Records executives.

“I actually feel kind of slighted when I don’t have that sort of guidance around me – mentors of that stature. And that also comes from growing up in Lafayette, on a musical level – being around people like Li’l Buck [guitarist Paul Sinegal] and players of that ilk and generation. I also met Doyle Bramhall (Sr.) at an early age, and he’s always been a guiding hand – both in music and in being a human being. He and Denny and Jack all instilled what it was to be a musician and have a heart – what making music and making art is about.”

Prior to working with Adcock, Jack Nitzsche’s most recent rock album was Graham Parker’s Squeezing Out Sparks, in 1979.

“I knew Jack’s name from the Stones and Phil Spector stuff,” Adcock admits. “But I had no idea how heavy this cat was and how deep it was going to get – that there were people on this planet who took rock and roll to that level. It was good to see that first-hand – that rock and roll is a cool art form and not just greasy kid’s stuff. Jack’s idea of producing certainly was not like it is today – like, ‘I’ve got some cool effects.’ His idea was, ‘Let me pump you up and play on all your strengths and help you recognize how to make greater your best assets.’ And then just knock you down to the most infantile, embryonic, heartless level, and build you back up again – and do that about 5,000 dozen times. Then you might be ready to sing a vocal. It was outrageous and grandiose – but that’s one the greatest qualities of my favorite rock and roll. He was one part Mozart and one part Fred Sanford.”

Being a product of both his time and geography, Adcock straddled commercial rock and regional traditions from his first band at age 12. “Zydeco and Cajun music and swamp pop were just always in the air. In Lafayette back then, you were into AC/DC, 13 years old, wearing the T-shirt at the mall – but ZZ Top sounded really good. And you could go to a festival and see Clifton Chenier, or go to Grant Street and hear the T-Birds. In Lafayette, you want to make people dance. We did Rolling Stones, along with hand-me-down blues records by Johnny Winter and Muddy Waters, and local Cajun and honky-tonk records. We were definitely into making music that made people dance, not music that made people sit around and think. So you’ve got to have a shuffle or a swing or a little zydeco rhythm. They’re not going to dance to ‘Back In Black’ or Rush. But some ’80s stuff was really about dancing, too. I mean, ‘Yall’d Think She’d Be Good 2 Me’ on the new CD – I’m sorry, that’s the Adam Ant, ‘Don’t drink, don’t smoke, what do you do?’ beat [“Goody Two Shoes”]. But it’s also a great parade beat that I heard in New Orleans when I was a kid. Same damn beat.”

“Swamp pop” is probably a more parochial style than even zydeco or Cajun, which have become universally popular over the past couple of decades.

“Warren Storm, who’s a founding member of that, will tell you that swamp pop is nothing but rhythm and blues,” Adcock points out. “I think it’s subconsciously more complex than that. It’s dance music, which it has in common with Cajun and zydeco, but it was the Cajun/Creole take on rock and roll and R&B. In the Deep South, things were a lot more integrated than even the history books understand. Blacks and whites lived amongst each other. No matter what the political situation was, there was a lot of interaction.

“So in that way, the food and the music, the culture, is borrowed back and forth and heavily influenced by one another. And I think it’s fair to say in that tradeoff, white people got a pretty good deal because black folks have great music and great food,” he laughs. “But after several generations of that tradeoff, it’s all one and the same. Swamp pop, like a lot of things down here, was a pretty color-blind trading of licks and styles. The rock and roll made down here is slightly more laid-back, and the singers are a lot more soulful. I’m not saying they don’t have good music and food in other places; it just don’t quite sound or taste the same. Swamp pop has more of a loping beat. A lot of people say it was based pretty strictly on Fats Domino, because he was, and still is, such an influential figure. His sound and style, and the whole essence of Fats, is about a good time. It’s a 6/8 triplet thing. But besides the rhythmic part, really sweet melodies are what swamp pop is all about, no matter how tough of a rock and roll song it is.”

Adcock’s debut CD included a stinging version of Bo Diddley’s “Bo’s Bounce” – or “Beaux’s Bounce,” as Adcock spells it. He reveals, “All that is is an Echoplex and a wooden Guyatone guitar that Bo gave me – then made me buy the case, for $75 – after he’d embarrassed me in front of a crowd of people because I’d been begging him to teach me what the trick was on ‘Bo’s Bounce.’ He tells me he doesn’t remember, then does it as the encore, with the drumstick trick [cranking the Echoplex and hitting the strings on the neck with a drumstick], and then hands me the stick. And I ain’t got no Echoplex. So I sit there and beat the **** out of a gorgeous Strat in the heat of the moment, trying to make it do what he just did, and having people chuckle and snicker. Then I hand it back to him and he does dibba-dibba-dibba-dibba with the stick, real fast, hands it back to me and I go whack-whack, doot-doot, swack-swack, really lame. Back and forth.

“Finally, I pulled something out – something that wasn’t ‘Bo’s Bounce’ – just to turn the audience my way eventually. It was like Bo Diddley had watched ‘Crossroads’ and wanted to mess my head up. But the joke was on him, because in those couple of minutes of me sweating it in front of a packed house, I got the gist of what he’d done. The next morning, by sun-up, I had it. And now I use it all the time; it’s such a great rhythmic thing to do. So thank you, Bo Diddley.”

Bo is just one of Adcock’s rootsy guitar influences.

“I start with the local guys, because I was able to see them at an early age,” he details. “There’s no way that listening to something on record comes close to being able to hear a record and then go see it, night after night. When you’re in those formative years, it leaves such a lasting impression on you. In that sense, I went to see Paul Sinegal, who played with Clifton and Rockin’ Dopsie. I saw him in clubs, at festivals, playing in the street at Mardi Gras, and we later had a band with him and me and Sonny Landreth, Cowboy Stew. Hearing Sonny early on – not so much trying to cop his style, because it was already ‘uncoppable,’ but the fact that he was playing something completely different made me think that was something to strive for. Then Gatemouth Brown, who played Grant Street it seemed every Saturday one summer when I was about 14. Seeing him play with his fingers, and the way he’d work a chromatic blues scale and make it so lyrical – I learned a lot about playing lead guitar by watching him.

“I got to see Earl King a lot, and I got the fact that he was a ‘bluesman’ but wasn’t playing blues; he was playing music – like Jimmy Reed. He was playing hits, not styles. And when he’d solo, he’d have that watery Strat sound, which always reminded me of New Orleans – that wet sound. He’d play solos by moving chords around, a half-step up or down; not lick-oriented things, but very musical. And getting to see Jimmie Vaughan with the Fabulous Thunderbirds – as a dance band. They didn’t have hits and weren’t on the radio, but they played Lafayette fairly often. Whereas Sonny was a Gibson guy at that time and had his Firebird – that warm, buttery sound – Jimmie was all about that big twang. I recognized that twang – that’s pretty much what an electric guitar was invented to do, unless you’re playing a supper club.”

Part and parcel of the big twang is Adcock’s penchant for tremolo and vibrato. “Sometimes I use a Magnatone M-15 with two 10s, and an M-13. When you get that Magnatone stereo vibrato going, that’s my favorite sound. I actually got the amp after I made the first record, so I could get the sound I got with an MXR phase-shifter and a blue Boss chorus. And any tremolo is good – whether it’s Ricky Martin or Britney Spears’ new record. When I put [masking] tape down on a mixing board, getting ready to track, around channel 21 or 22 I always put ‘trem.’ I know eventually there’ll be at least one tremolo pass. It just makes stuff sound better. It’s like the genesis of electric guitar effects. It never gets old; it’s always good. What sounds better than ‘Rumble’ by Link Wray or whoever was playing guitar on Isaac Hayes stuff like ‘Walk On By’? I actually like the tremolo that cuts off. I like front-porch tremolo, that’s got a nice peak and valley to it, but I also like to just get the old machine-gun tremolo going, too – where it actually stops, like a delay almost. Max intensity, but with no peak and valley – literally like a cut.”

But his technique probably accounts for his tone more than his choice of equipment. “There’s distortion always,” he begins, “just because it’s amplifiers turned up loud. Everything I own is sort of broken. I need at least two or three of everything just to equal one. So a lot of times, things will short out on a gig, and I’ll just bypass everything and go straight to the amp. A lot of it is the way you pick, using your fingers, playing back by the bridge, the attack. That’s something I picked up from the different guitar players I was listening to – how varied everyone’s approach was. I’d play Li’l Buck’s guitar, and he had, like, .008s on there – super light, but a huge sound. Then Sonny obviously running his hand up behind the slide; and Gatemouth playing with his finger, just finessing it; and Jimmie, who sounded like a wall-of-twang orchestra in, basically, a three-piece band. He was so deliberately playing simple. His left and right hands were very deliberate gestures. The way he’d play Jimmy Reed was like, ‘Check it out, dude; I’m playing Jimmy Reed.’ And doing nothing but Jimmy Reed – and listen how good it sounds. Subtlety, when you’ve got a pompadour, wearing flashy clothes.

“I was watching people evoke various tones out of instruments, no matter what the instrument or amp was. I use the tone knob on my guitar a lot. No matter what guitar I’m playing, I find you can really make them sound better usually by rolling the tone off a little bit, and then using the tone as a dynamic like you use a volume knob.

“The way Nitzsche would arrange was based on frequency as much as volume or thickness. He’d figure out a part not based on what notes needed to be there as much as what frequency of sound needed to be there. You can put an amazing amount of things in one place without it sounding cluttered or overdone, and still have it sound real simple, and really groove, as long as you don’t have a lot of overlapping frequencies. Even in a three-piece, if you’re playing rhythm and you’ve got your tone wide open, and you jump into a solo, you can still have a bunch of volume, but turn your tone all the way down and make a real muddy sound. Invite people to come into you and listen. Then later on in the solo, when you need to sting it, you can jack up that tone, and it sounds like you just brought it big-time. And it certainly helps with distortion.

“Even if you don’t have the right ****, no matter how rank the distortion is, if you turn the tone down to zero, it sort of sounds like Hendrix,” he adds, laughing.

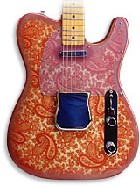

In addition to Teles and his ’66 Strat, some of the guitars Adcock is most associated with are James Trussart’s metal-bodied electrics.

“James is making great guitars. It’s pretty hard to improve on what Fender and Gibson and Danelectro did along the way, but his guitars all have that great intersection of being completely stylish and cool and different, without compromising sound or the way they play. I love his guitars. I outfit them with different things, based on whether they’re hollowbodies or semi-hollow, or if I want them to sound more like Teles or Gibsons.”

On the other hand, Adcock says, “I personally like Mexican Fenders. It’s kind of like what CDs have done for reissues. They’re stamping out guitars now that play, look, sound, and are set up great, and they’re getting it right. The best new guitar I’ve played in a while was one of those Jimmie Vaughan Fender Strats.”

Adcock’s overriding philosophy and objective is something he learned from his guitar heroes, although he views it as something bigger than the instrument.

“I got to play with Hubert Sumlin several times, after years of listening to those records with Howlin’ Wolf,” he smiles. “And whether it’s Hubert or Bo or Sonny or Hendrix, it’s all about trying to use the guitar as an instrument of making music, not as playing guitar – approaching a solo as an outlet for emotion. How to get sounds out of the guitar, and whatever works for the song, not what licks can I play here. When I’m really playing good, and my mind is opened up and I’m having a great night, I feel like the whole guitar and the effects pedals and the volume and the sound and rhythm – it’s just like putty in your hand, and you can do whatever you want to with it. There’s zero rules – no matter how goofy you want to get. Just get some sound out of this box, right now, and make some people feel that that sound has something to do with your interpretation of the vibe you’re trying to get across.”

Photo: Terri Fensel, courtesy of Yep Roc.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Feb. ’05 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

.jpg)