Somewhere in the world right now, a Foreigner song is playing on the radio. Literally. Thanks to nearly 20 mega-hit singles, 75 million units sold, and legions of fans, the band has earned a solid place in pop-music history.

Somewhere in the world right now, a Foreigner song is playing on the radio. Literally. Thanks to nearly 20 mega-hit singles, 75 million units sold, and legions of fans, the band has earned a solid place in pop-music history.

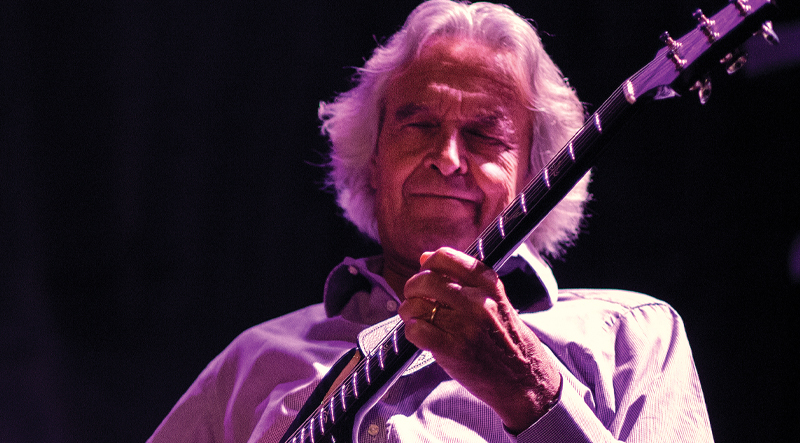

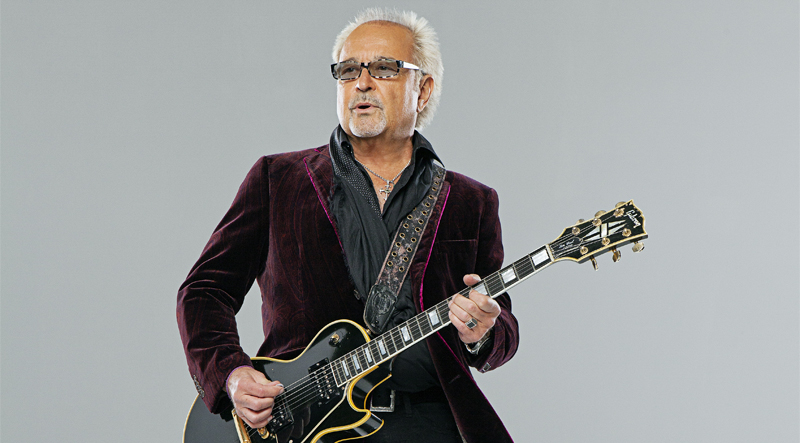

Founder, guitarist, keyboardist, vocalist, songwriter, and producer Mick Jones guided the group to dizzying heights from the late 1970s through the late ’80s as it created some of the most popular songs of the era – “Feels Like the First Time,” “Cold as Ice,” “Long, Long Way from Home,” “Hot Blooded,” “Double Vision,” “Blue Morning, Blue Day,” “Dirty White Boy,” “Head Games,” “Urgent,” “Waiting for a Girl Like You,” “Juke Box Hero,” “Break it Up,” “I Want to Know What Love Is,” “That Was Yesterday,” “Say You Will” and “I Don’t Want to Live Without You.”

Founder, guitarist, keyboardist, vocalist, songwriter, and producer Mick Jones guided the group to dizzying heights from the late 1970s through the late ’80s as it created some of the most popular songs of the era – “Feels Like the First Time,” “Cold as Ice,” “Long, Long Way from Home,” “Hot Blooded,” “Double Vision,” “Blue Morning, Blue Day,” “Dirty White Boy,” “Head Games,” “Urgent,” “Waiting for a Girl Like You,” “Juke Box Hero,” “Break it Up,” “I Want to Know What Love Is,” “That Was Yesterday,” “Say You Will” and “I Don’t Want to Live Without You.”

In 2017, Foreigner marked the 40th anniversary of its self-titled debut album with a tour, the two-disc compilation 40, and Jones’ autobiography, A Foreigner’s Tale.

Despite Foreigner’s rapid rise, Jones was hardly an overnight success. The Brit spent years making his bones in bands like Nero and the Gladiators before backing Johnny Hallyday (the “French Elvis”), then joined Spooky Tooth in ’73/’74. For a quick few months in ’76, he was a member of the Leslie West Band before being left nearly broke in New York.

“Everything somehow came together in my life,” he recalled. “I’d been floundering around in New York and had to make a living. I was thinking of going back to England, when suddenly I started writing a bunch of songs. I thought, ‘What am I going to do with these? Oh, of course. Form a band!’ That was really the start of it and it just started growing from there. The excitement started to ferment.”

Manager Bud Prager found rehearsal space for Jones to audition members of a new band, and among those to show up was vocalist Lou Gramm. A lineup quickly solidified and the group eventually signed with Atlantic Records.

“I’d gotten used to the life around the excitement of stage, studio, and producing. So I had an arsenal to dig from,” said Jones.

Foreigner’s blend of riffs, power chords, hypnotizing hooks, and melodies appealed to rockers and pop fans alike. Its style evident from the beginning, success was almost instantaneous as Foreigner shot up the charts and saturated airwaves.

Looking back, Jones recalls feeling that the album was a solid collection of songs, and he was cautiously optimistic a hit single could emerge.

“I didn’t so much think of monster hits. I thought they were really good album tracks and there might be a shot at a single, but there were no high expectations. We were prepared to slog it out and try to build a reputation.”

He had no idea.

“Everything that happened was crazy,” he added. “It gradually came together. There were problems finding the right makeup of the band, but we overcame them. And we were lucky to find a champion at the record company in John Kalodner.”

Radio was crucial in breaking the band. Atlantic’s staff loved Foreigner, but since the band was a new signing, it hadn’t attracted much attention from founder Ahmet Ertegun, who was focused on his superstar acts, not using his power and influence to open doors. But Foreigner would soon become a priority.

“We didn’t get special treatment from Ahmet at that time,” said Jones, who’s now 72. “He was busy with the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin. We had to earn our association with him, and it had a lot do with staff being very into the album. They loved it.

“When I look back on ‘Feels Like the First Time,’ it was a very pivotal start. It was the first song that I’d written by myself for several years. As corny as it sounds, it did feel like the first time! I couldn’t believe it, really. We’d hear all of these incredible stats about sales and airplay, but it was so far beyond our expectations. It was a nice surprise, I have to say! Those were very giddy times.”

Hitting the road near the release of Foreigner rapidly built the fan base.

“We did some club dates and a few bits of tours here and there with Ted Nugent and Uriah Heep. The first break, really, was getting to tour with the Doobie Brothers. That gave us great exposure. They were a very hot band at the time and something to compete with. Everything went great. They were very kind, and helped nurture us a bit.”

Foreigner enjoyed triumphs with Double Vision, Head Games, 4, Agent Provocateur, and Inside Information, all of which sold millions.

The public embrace practically guaranteed an unkindly response from music critics. Jones isn’t exactly sure why they ripped Foreigner.

“There was a feeling they didn’t have any part in discovering the band, due to the nature of the way we formed,” he said. “But I’ve been able to talk with many that were closet Foreigner fans. Like [Rolling Stone and Creem critic] Lester Bangs, whose forté at the parties was playing air guitar to ‘Hot Blooded.’

“It was the same with [Sex Pistols vocalist] Johnny Rotten at one point!” he laughed. “The number of musicians and younger bands these days that quote my name as an big influence is very gratifying. We were never the critics’ darlings. I think with 4 they started to pay more attention because we did stretch out a bit, but you have remember that we came out of the dawn of punk and new wave – even disco was huge! We had a lot to combat.”

In fact, Foreigner took critical darlings like the Ramones and the Cars on tour with them.

“I was interested in a lot of contemporary music… always have been,” said Jones. “I keep my ear to the ground. I listen to what my children are getting into.”

Wearing so many creative hats can be exhausting, but Jones thinks of himself primarily as a guitarist and songwriter. He fused the two roles to create a signature style.

Wearing so many creative hats can be exhausting, but Jones thinks of himself primarily as a guitarist and songwriter. He fused the two roles to create a signature style.

“I’ve always figured it’s halfway between rhythm and lead. Pete Townshend was a big influence on me, on back to Chuck Berry; he was probably the best combination of lead-guitar and incredible rhythm. That motivated me to go for the feel. Foreigner is a guitar-driven band, really. Much more these days than it probably was at the beginning.”

Speaking of guitars, Jones has used just a handful over the years. His first decent electric was a Burns, a popular brand in England in the ’60s. Early in his professional career, he moved to a Gibson SG, then an ES-345.

“The 345 was almost identical to the one Chuck Berry played. It was a rich orange-red color – my favorite guitar. It was a real classic and had a lot of history. Unfortunately, it was stolen. Instead of getting another, I bought my first Les Paul in the mid ’70s.”

His arsenal during the Foreigner years included two single-cut Les Pauls. He also has an appreciation for Teles and Strats. When he tracked guitar parts on Foreigner records, he enhanced the tone of the Les Paul by layering on a Tele to give it sparkle. His attraction to the Strat is the influence of his early idol, Buddy Holly. Jones also owns a handful of Precision basses and Gibson J-200s.

“I own probably about 30 guitars,” he said. “I never was an avid collector. I just occasionally bought one if I’d see something interesting. There were a few choice stores on the tour circuit. We’d arrive a day early and have a look around.”

Jones co-produced all of Foreigner’s albums with heavy hitters like Keith Olsen, Roy Thomas Baker and Robert John “Mutt” Lange. Spending time in the studio may have been a necessary evil, but he wasn’t glued to a console.

“We took time doing the albums and spent a bit more than we needed to, sometimes, but it paid off pretty well.

“Now, I get claustrophobic spending too much time in the studio. After 4, actually, I started feeling like the studio was leading the pack.”

Contributing to his growing restlessness at the time was work as producer on Van Halen’s 5150 along with Billy Joel’s Storm Front. In the wake of their success, he turned down other producing opportunities.

“That’s when I really started to feel trapped. Doing the Van Halen album was intense in what was a very small control room. They were highly excitable boys! Working with them was great and I got to understand just how gifted Eddie was. It was a learning experience. A big one.”

Through the late ’80s, Jones kept a grip on Foreigner though his creative partnership with Gramm was splintering. In ’87, they released the troubled Inside Information and in ’89 Jones issued his star-studded solo album with appearances by Joel, Ian Hunter, Carly Simon, Hugh McCracken, Joe Lynn Turner, Simon Kirke, Steve Ferrone, and others. Gramm, who was launching a solo career, left Foreigner and was replaced by Johnny Edwards for 1991’s Unusual Heat. Gramm was back in the fold by ’92 and Foreigner soldiered on until dissolving in 2002, when he departed once again.

In ’05, Jones revived Foreigner with vocalist Kelly Hansen, former Dokken and Dio bassist Jeff Pilson, and saxophonist/guitarist/keyboardist Tom Gimbel. Their first album was 2009’s Can’t Slow Down and Jones said the four of them work well together.

“They’re really into it. The dedication is intense; Kelly gives 200 percent every night and there’s a really good vibe – no sour grapes, no baggage. Just great musicianship. It shows with the crowds. Through some problems I’ve had the past few years, health-wise, they’ve carried the flag. I owe them a lot and I’m so appreciative they’ve stuck with me through thick and thin.

“The longevity has proved itself. We’ve strived for the last 12 years to invent a new Foreigner legacy, and it seems to be paying off. We never did a lot of video or photo sessions, so a lot of people didn’t really remember the band. They remembered the songs. But I think we’ve regained stature and have a lot of kids coming to shows, plus there’s the more-mature audience, as well. The atmosphere is as strong as it’s ever been for me, with crowd participation and excitement.”

Fans at certain shows in the summer and fall were treated to guest appearances by alumni; Gramm, drummer Dennis Elliott, keyboardist Al Greenwood, guitarist/keyboardist/saxophonist Ian McDonald and bass guitarist Rick Wills all participated (original bass guitarist Ed Gagliardi died in 2014). Wills appeared June 11 in Marbella, Spain. Gramm, Greenwood, and McDonald sat in July 20 Wantagh, New York. Elliott played August 2 in Tampa, Florida. The biggest news was Elliott, Gramm, Greenwood, McDonald, and Wills all performing on October 6 and 7 in Mount Pleasant, Michigan; both nights were filmed and recorded for a forthcoming television special/DVD/album.

New music from Foreigner is forthcoming.

“I’m working with a fantastic cellist named Dave Eggar,” Jones said. “It’s been so exciting working with him – he’s innovative and fresh and powerful.”

Though his career has been loaded with highlights including a Grammy nomination for Best New Artist in ’77, being inducted with Gramm into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, having saxophonist Junior Walker cut the solo for “Urgent,” topping the Billboard album chart with 4 and the singles chart with “I Want to Know What Love Is,” there’s one particularly vivid memory for Jones.

“The first time we played Madison Square Garden was huge because I live in New York. Everybody was there from the label, and I had my parents there from England. I remember thinking, ‘Wow, it doesn’t get much better than this!’ But it did.”

This article originally appeared in VG January 2018 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

“I first met Tom and the Heartbreakers on the Dogs With Wings Tour in the summer of ’95. I had just joined Pete Droge’s band and we were their opener for a two-month trek across the U.S. A fan since day one, I’d seen them a few times, so I was excited. After our set, we’d often stay to watch theirs. It was like going to school. Their energy, the pacing, the extended jams on songs like ‘It’s Good To Be King.’ Production and sound were always stellar, Tom’s interaction with the audience was warm and sincere, his gestures grand.

“I first met Tom and the Heartbreakers on the Dogs With Wings Tour in the summer of ’95. I had just joined Pete Droge’s band and we were their opener for a two-month trek across the U.S. A fan since day one, I’d seen them a few times, so I was excited. After our set, we’d often stay to watch theirs. It was like going to school. Their energy, the pacing, the extended jams on songs like ‘It’s Good To Be King.’ Production and sound were always stellar, Tom’s interaction with the audience was warm and sincere, his gestures grand.

The Master Model instruments created at Gibson in the early 1920s are famous for their sound and build. Credit for their design is often laid at the feet of “acoustic engineer” Lloyd A. Loar, but recent study calls into question the role he played – and may even position him as a mere tool of the company’s marketing.

The Master Model instruments created at Gibson in the early 1920s are famous for their sound and build. Credit for their design is often laid at the feet of “acoustic engineer” Lloyd A. Loar, but recent study calls into question the role he played – and may even position him as a mere tool of the company’s marketing.

Befitting a guitarist from America’s heartland, Charlie Ballantine’s mixes jazz, folk-rock, surf/instro, blues, pop, and country into a simmering pot of guitar sound and style. His instrumental work is beautiful and complex, ranging from melodic journeys to raging heavier sounds. Charlie’s latest CD is Where is My Mind?, a strong album that marks him as a young player to watch.

Befitting a guitarist from America’s heartland, Charlie Ballantine’s mixes jazz, folk-rock, surf/instro, blues, pop, and country into a simmering pot of guitar sound and style. His instrumental work is beautiful and complex, ranging from melodic journeys to raging heavier sounds. Charlie’s latest CD is Where is My Mind?, a strong album that marks him as a young player to watch.