Explore the G blues scale with acclaimed mandolinist Andrew Hendryx. Originally appeared on a Facebook Live Lesson on Sunday, April 5th, 2020. Keep up with Andrew HERE!

Explore the G blues scale with acclaimed mandolinist Andrew Hendryx. Originally appeared on a Facebook Live Lesson on Sunday, April 5th, 2020. Keep up with Andrew HERE!

Given that tone guru Ken Fischer is no longer with us, Trainwrecks are arguably fixed to an even higher standard by the laws of supply and demand. Please welcome, then, this rare appearance of “Nancy,” an early Trainwreck Express model built by Fischer in 1986 in his New Jersey shop. One of what is believed by its maker’s own estimation to be “probably 100 Trainwrecks in the world,” Nancy (Fischer used feminine names on his amps rather than serial numbers) is nevertheless no under-glass collector’s piece, but a living, (fire) breathing tone machine that has continued to pay her way in the hands of hard-working musicians since rolling out of the shop 23 years ago, and that’s more than you can say for a lot of $35,000 vintage gear out there today.

Owned for the past five years by guitarist and producer Matte Henderson, who has worked with everyone from Henry Kaiser and Robert Fripp to Jewel and Natalie Merchant, Nancy was previously played for many years by a hard-gigging guitarist from Texas, whose taped-on notes “5” and “6” still adorn the input and speaker outs, reminders of which cable goes where.

Although Fischer maintained two relatively steady models in the Liverpool and the Express, and added the Rocket to the lineup a few years later, each amp really was an individual creation, and no two were ever exactly alike. Each was tweaked to suit his evolving notions of perfect tone, and to meet the desires of the player for whom he was building it, and components also varied throughout the decade and a half that he was manufacturing amps. Recalling his first encounter with Trainwreck, Henderson tells us, “Henry Kaiser invited me to California to record with him in 1990, and he had eight Dumbles at the time, so I was really looking forward to trying those. When I got there, he said, ‘I just got this amp here…’ and plugged me into a Trainwreck Liverpool. I just went, ‘Oh my God, I’ve got to get one of these!’ So I bought a Liverpool from Kenny, and an Express after that.” In addition to becoming a customer, Henderson also acted as a handy phone demo guy for Fischer: potential customers would discuss the amps with the maker, then call Henderson for a quick over-the-phone playing demonstration to hear what they sounded like.

The Liverpool and Express are differentiated, most obviously, by their use of four EL84s and two EL34s, respectively. As a result, the former is usually referred to as being “Voxy” to the latter’s “Marshally,” though every one of each model is also quite different from either of those vintage British brands. Nancy further differentiates itself from later Expresses by being one of the earlier versions made with the Stancor transformers from the Chicago Standard Transformer Company, which Fischer used from 1985 to ’89. As Fischer himself related, “In 1989… Stancor stopped making those transformers, so I bought up all they had left of those to get me through the year with a few spares.” Post-1990, he used “…about 12 different transformer companies.”

Aside from merely being historically interesting, the use of Stancors in the earlier Expresses such as this one also signaled a different sonic signature. Where later “black tranny” Expresses leaned more heavily toward high-gain tones, the Stancor Trainwrecks, though still plenty gainy when you want them to be, had a slightly browner, more vintagey blues-rock vibe. “It’s more of a small-box ’68 Marshall,” Henderson confirms. “Tube tuning is what these amps are all about; they run fairly low plate voltages (around 380 volts DC on the EL34s).” What really makes Trainwrecks tick, of course, is the circuit going on underneath the hood, and more than that, the way Fischer laid out the components, connected the wires, and selected individual resistor and capacitor types and values by hand to fine-tune the overall tone and feel of the amplifiers. The intense skill that the man applied to his craft is further attested to by the fact that, while other makers have lifted the lids on existing Trainwrecks and copied their circuits, any experienced Tranwreck player will tell you that none of these so-called “clones” ever quite attains the sensitivity and complexity of Fischer’s own creations.

In addition to – arguably in contrast to – their unparalleled electrical workings, Trainwrecks sported decidedly DIY-looking cabinets and cosmetics. As a case in point, check out Nancy’s polished hardwood shell and front panels, the wood-burner etched control legends and starburst motif, and the stick-on Dymo labels that tell you what’s what ’round the rear. Guitarists who were not in the know years back could be forgiven for passing one of these over as some tubehead’s basement Marshall-like project, but any player who had a shot at one for reasonable money in the late ’80s or early ’90s and didn’t bite is certainly kicking themselves now.

The first Trainwreck Liverpool rolled out the door in 1983 at a price of $650. A year later that was raised to $1,000 for either model, then through the course of the ’90s inflation took it to $1,200, then $1,600, then finally $1,800 as the cost of parts increased. Long unable to build any new amps due to a raft of illnesses, Fischer saw the price of used Trainwrecks rise to $22,000 or more during his lifetime, and in the three years since his death on December 23, 2006, good Trainwrecks have pushed past the $30,000 mark. While he was still making amps, he not only offered customers a two-week trial with a full money-back guarantee, but declared he would refund the cost of shipping both ways if a buyer wanted to return his amp. None ever did.

Shortly before his death, Fischer revised the offer. “Several years back I instituted a policy; any Trainwreck amp out there has a ‘triple-your-money-back’ original-purchase-price guarantee. So if you’ve got a Trainwreck and you don’t want it any more, send it back to me and I’ll look up the original purchase price and refund it triple.” As it happens, the “new policy” had no takers either.

Dave Hunter is an American musician and journalist who has worked in both Britain and the U.S. He’s a former editor of The Guitar Magazine (UK).

This article originally appeared in VG May 2010 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

The Stathopoulo family legacy starts in 1903, when 40-year-old Greek immigrant and luthier Anastasios Stathopoulo came to New York. He established himself as a maker and importer of instruments, including Greek bouzoukis, mandolins, and even violins and cellos. A fine example of his early work is the 1907 mandolin (shown here) that was sitting on a shelf in Epiphone’s Nashville headquarters. The basic design is similar to other bowl-back mandolins of that period, but also shows off the skills of a very experienced luthier, with beautifully intricate inlay and purflings made of mother-of-pearl, abalone, and ebony, with a solid tortoiseshell bridge and inlaid pickguard.

In 1909, Anastasios (not yet a U.S. citizen) patented a “new, original and ornamental design for the Mandolin” (Pat. 40,010). Its most striking feature was the cello-style scrolled headstock with a carved animal’s head that appeared on several of his instruments. Tragically, this era ended abruptly in 1915, when Anastasios, a 52-year-old husband and father of six, died from “a long illness.”

By 1917, the newly christened “House of Stathopoulo” ushered in the second era in the history of the family’s growing musical instrument business, including the first of three banjo designs by Epi Stathopoulo, Anastasios’ eldest son and general manager. Unfortunately, little is known about this period following Anastasios’ death by way of advertising or company catalogs. A 1920 trade magazine, The Violinist, barely mentions the Stathopoulo shop on West 39th Street, despite its self-proclaimed 40 years of experience as a dealer and importer of violins. It would take several years before the Epiphone name became synomous with high-quality instruments like the Recording banjos of the 1920s and the Masterbilt archtop guitars of the ’30s.

There are no company catalogs or price lists with harp guitars, and strangely, no mention of a harp guitar in the Epiphone book. The label inside the body identifies “House of Stathopoulo, New York” as its maker, yet the harp guitar seems to lack the “quality workmanship, strength, and durability” stated on it. The missing corner of the label may have had a date, and the hand-written “No. 781” doesn’t narrow it down, since there are no serial number records prior to 1935. Although previously dated as circa 1910, it’s far more likely the harp guitar was built between 1920 and ’22, and clearly is not the work of a master craftsman like Anastasios Stathopoulo, which would have dated it to pre-1915.

The enormous two-piece rosewood back still has visible kerf marks from a lack of adequate planing and scraping. All six linear feet of the higher-grade rosewood rims are nicely formed, but not quite a match to the back. The shape of the mirrored pegheads may have inspired another Greek-American luthier, one Clarence Leonidas “Leo” Fender, but are a bit crude with more visible saw marks, indicative of a novice builder. They join each of the two necks with loose V joints that split and cracked under the strain of the strings. Scott Harrison, head of Epiphone’s R&D department, can point to several poorly repaired cracks, sloppy refinishing, and patches, extra bracing, and enough excess glue inside the body for three harp guitars. The massive rosewood bridge anchors the six strings and six sub-bass strings, but three extra holes in the peghead seems to indicate it once had a total of 15 strings. The bare spot on the top was probably the pickguard’s location, but no evidence of what type, or if it was original or added later. However, there are several design features that are distinctly Epiphone, including the mother-of-pearl fingerboard inlays of varying shapes and sizes, and the seven-piece laminated neck construction.

The heart-shaped sound hole, off-center bridge, and asymmetrical 20″ lower bout help it stand as a one-of-a-kind creation and provide a glimpse into a transitional period prior to the formation of the Epiphone Banjo Corporation. It also speaks volumes about how the Stathopoulo brothers struggled to establish an identity building new, original designs.

This harp guitar provides a link between The House of Stathopoulo and the Roy Smeck Octochorda, another unusual eight-string Hawaiian guitar that until recently had never been associated with Epiphone. Stories floating around about the origins of the octochorda credit Sam Moore, a vaudeville-era novelty instrumentalist, as being its inventor. Well, Moore may have been the first performer to use an octochorda, but a 1922 article stated it was invented by Harry Skinner of Chicago, who worked in Lyon & Healy’s violin department. Skinner also co-authored Moore’s first hit, “Laughing Rag,” with Moore on octochorda. A 1924 photo showed the vaudeville team of Moore and Freed as “…enthusiastic users of Lyon & Healy Instruments” with Moore playing their Bell Guitar.

Sometime in 1923, another talented multi-instrumentalist, Roy Smeck, met Moore while on the Orpheum and Keith vaudeville circuit, and according to Vincent Cortese, author of Roy Smeck: The Wizard of the Strings in His Life and Times, Smeck said, “Sam Moore invented the octachorda tuning” (open E7) and “[Smeck] was the only other one to play the octachorda in vaudeville.” Smeck also stated that his octochorda was one of only two made, but “[Sam’s] was a regular guitar, without the heart-shaped sound hole.” A music-trade editorial from June, 1924, supports Smeck’s claim and specifically mentions the octachorda as “the only one in its existence.” The logical conclusion is Harry Skinner’s invention was probably an eight-string version of the Lyon & Healy Bell Guitar, not an earlier version of Smeck’s octochorda. Several other accounts credit the Harmony Company with building the octochorda, and Smeck himself is mainly responsible for this story. “Roy told me Harmony built the octochorda,” said Cortese. But after seeing pictures of the House of Stathopoulo harp guitar, commented, “Now you got me scratching my head… everything happened for Roy after the Vitaphone film,” including his association with Harmony.

Vinny was, of course referring to Roy’s overnight rise to stardom after appearing in Warner Brother’s 1926 Vitaphone short film, His Pastimes. Roy was signed for $350 by Harry Warner, one of the four original Warner Brothers, to appear in what became Smeck’s chance of a lifetime. On August 6, 1926, more than a year before Warner Brothers released the first feature length-talking picture, The Jazz Singer, highbrow New Yorkers paid a whopping $10 to see the feature film Don Juan, starring John Barrymore. The prelude included a series of short talkies by renowned artists of the day like operatic singers Anna Case and Giovanni Martinelli, Ephrim Zimbalist, Sr., and the newly discovered “Wizard of the Strings,” Roy Smeck. As New Times reviewer Mordant Hall wrote the next day, “The seductive twanging of a guitar manipulated by Roy Smeck captured the audience. Every note appeared to come straight from the instrument and one almost forgot that the Vitaphone was responsible for the realistic effect.” In fact, this was no mere guitar, but the then-unknown octochorda.

In 1927, the President of Harmony, Jay Krauss, approached Roy with an endorsement deal to take advantage of the incredible success of the Vitaphone film and introduced the Vita-Uke, followed by several other designs including the six-string Vita-Guitar. Some of these “novelty” instruments had sound holes shaped like trained seals, and others had airplane-shaped “aero-bridges,” meant to capitalize on the celebrity of Charles Lindbergh. It certainly paid off, as a reported 500,000 units were sold in the first three years. The wizard had his octochorda long before Harmony came knocking. Further proof is an editorial from 1924 announcing that Smeck was signed by Paul Specht’s Alamac Orchestra for “orchestral and solo recording work” using seven instruments, including the octochorda. This was after the tour with Olga Myra and the Southland Entertainers, when Roy first met Sam Moore

Unfortunately, the octochorda disappeared circa 1930. One account says it was stolen from Smeck’s hotel room, but another explanation is his brief marriage and ensuing divorce from Olga Myra, a contortionist/dancer/violinist, who “…left me with $7 and a ukulele.”

The octochorda doesn’t appear on any Smeck recordings after 1928, and apparently vanished from the face of the earth. That is until one fateful day in 1994, when uke collector Randy Klimpert visited an antique shop and noticed a strange instrument, tagged “Circa 1890 Handcrafted: Possibly Spanish.” The shop owner offered a creative tale of his own, telling Klimpert it was “…made by slaves for their master during the Civil War.” Without knowing what it was, Klimpert bought it and after a bit of research realized it was in fact, the Roy Smeck Octochorda. In a cruel twist of fate, it happened just months after Smeck died at age 94.

Nobody knows how the octochorda wound up in an antique shop, and there are few clues regarding its life after Smeck. One exception is its appearance in the 1973 book The Steel String Guitar, by Donald Brosnac, in which it appears with the caption, “Harmony Octochorda 1929 – Photographed at the Harmony Guitar Co.” and sporting a giant carved-eagle bridge that was not on Smeck’s ’20s version. At some point, Harmony could have added the bridge and claimed the instrument as their own design, but the 1929 dating is clearly not accurate.

As it turns out, the harp guitar and octochorda were not the only two examples of these unique designs. A photo belonging to renowned harp guitarist Gregg Miner shows a similar instrument with six strings – a “sextachorda” with mother-of-pearl and abalone inlay and purfling around the body and sound hole. Though its peghead is obscured in the photo, there is a faint outline of a standard six-string slot-head configuration, and it is shown being played like a conventional six-string, not lap-style.

So, the harp guitar, Roy Smeck’s octochorda, and the sextachorda share many traits. Were they designed and built by Epi Stathopoulo himself? Perhaps, as all three share the downward-slanting cutaway that would reappear on Epiphone’s Recording Guitars of the late 1920s/early ’30s. In a sense, the octochorda’s cello-style scroll-top peghead is a fitting tribute to Anastasios Stathopoulo’s 1909 mandolin design, and brings our story full circle to when a Greek immigrant wanted to make instruments that would stand out.

Copyright 2009 Paul M. Fox.

This article originally appeared in VG May 2010 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

The band and its musical patriarch have defined resilience in their march forward, keeping the music fresh and vibrant with longtime friends/co-guitarists Rickey Medlocke and Hughie Thomasson, regular album releases, and diligent touring.

And the fates have given Rossington no breaks. In early 2003 he underwent triple-bypass heart surgery. But the guitarist, far from being the type to complain, was soon back at it, recording and prepping a world tour.

We recently caught up with Rossington, Medlocke, and Thomasson as they set out on the road to support their latest offering, Viscious Cycle, and soak up some of the rewards that come with being veterans – like having Gibson/Epiphone issue no fewer than three guitars in their honor!

Vintage Guitar: What inspired you to become a musician, and how did the guitar become your main instrument?

Gary Rossington: It was actually Elvis, way back when. I used to take a broom and play it in front of a mirror, like him on guitar.

Then, when the Beatles, Stones, and all of the British groups came out, that’s what got me going. I was 13 or 14 when the Beatles came out and Allen, Ronnie, and me saw those guys [and] thought they were so cool. We wanted to be like them, and I wanted to play guitar! I thought guitar was the neatest thing. We taught ourselves and went for it.

What was your first guitar?

I still got it, believe it or not – an early-’60s Silvertone from Sears I bought with money from doing a paper route. They had an acoustic for eight bucks. Then they had this electric with a case and a speaker in it. I got that one and I still own it – and it still works.

What’s the story about how you got your 1959 Les Paul?

The first time we were ever in Nashville, playing a club called the Briar Patch, a girl said she had a Gibson Les Paul in her closet. That’s all she knew.

So we went to her house and it was a nice Les Paul. It was in great shape, but you could see it hadn’t been picked up for a long time. They didn’t know what they had and they wanted to sell it for $1,000. So I went back with $1,000 and they said, “No.” Somebody told them it was worth $2,000 to $3,000. I told them not to sell it.

A few weekends went by and we were playing that club again, so I went over and got it.

Why did you name it after your mother, Bernice?

My father died when I was 10, so my mother raised me. She helped us get the band going, and helped me buy guitars. I had a paper route, but she put money in even though we didn’t have much. I just loved her a lot and missed her a lot when I was on the road, so I called it Bernice.

When did Gibson approach you about the Rossington signature Les Paul and SG guitars?

A year or so ago, a guy from Gibson called and asked if he could copy mine to do a signature model. I thought it was the neatest thing since sliced bread, because I love Gibson guitars. I’ve always played Les Pauls, and bought a lot of them. But they wanted to do this in honor of me, and it is such an honor!

They had Bernice for about a week. They drew it out and re-created the scars, nicks, and scratches, then put the same pickups, knobs, electronics, and hardware on it. It looks just like my original. They did the same with the ’61 SG I played “Freebird” on.

I’ve had a few other guitars throughout the years, but I’ve still got both originals. I use one [of the signature models] onstage now because I don’t want to take the originals out. I’ve used both for “Freebird” and one of the signature Les Pauls for the whole set. It’s real nice. It sounds great and stays in tune. I love it!

What gauge of strings do you typically use?

I use .010, .013, .017, .026, .036, .046 Dean Markleys. They’re great.

What amps are you using live and in the studio?

In the studio, I’ve always used the same Peavey Mace. It’s 25 or 30 years old. I put new tubes in it every year, as well as new wires and fuses when it needs it. It sounds really good.

We got a deal with Peavey long ago; Hartley Peavey gave us a couple of amps, and we been using ’em ever since. I think they sound great.

We used to use Marshalls, and Rickey still uses Marshalls. We also used Line 6 Amp Farm [software] in the studio, which sound like just about any kind of amp.

Talk about Vicious Cycle. What was the inspiration for the material?

I’m proud of that album because we worked so hard on it. We put our hearts and souls into it to show people that [although] there are new faces, we’re the same band and the same spirit. We had to prove we’re more than just an old band playing old songs. We got a couple new writers, and some of the songs were taken from real stories. We tried to write about things that are going on today, and about the way we felt.

We try to keep our style and sound – be the real deal, and not use a bunch of effects, so we can play ’em live!

Everything we write or put on a record, we want to be able to play live, if people like it. So we did all that on this record.

I believe this year we had something to prove, what with the new faces in the band. There was a lot of talk about why we were still going on. When you’re involved with something like this, it’s bigger than all of us. People want to hear the old songs and the new. We’re gonna play a bunch of ’em this summer along with the old, and it’s going to be fun. When we play the old songs, I feel Ronnie, Allen, Steve, and Leon – all of them – onstage with us. It’s spiritual.

What inspires your songwriting?

I think it comes through you. Any guitar player can come up with a few riffs. [Once I come up with a riff], I add to it and Rickey, Hughie, and Johnny will expand on my idea. With lyrics, once we get an idea, we sit around and throw lyrics back and forth.

Most of the songs are true stories. “Hell Or Heaven” is about people I see every day; they’re in hell because of their life, what they got themselves into, or the way they think about everything. But they can make heaven on Earth if they just appreciate the good things in life.

“Lucky Man” is about why we all feel so lucky. We’ve been through a lot of tragedy and a lot of hard times. But you know it’s just life. And if you look at some places around the world, you think about how bad those people have it… they don’t even have food or water. It makes you think about how lucky you are.

We’ve had a lot of bad luck and bad accidents, but we’re so lucky to be able to be playing music and to be in America. We have fans come every night, and families who love us. What more do you need? We’re lucky to be able to play music and do something we love. Skynyrd lives on. The name, the music, and all the guys.

As long as we can play the music they helped create, they’re still alive and people will remember them. It’s a big thing and I feel lucky to be a part of it.

“Red, White and Blue” has been embraced as a patriotic anthem. How did that song come about?

That was written by Johnny, Donnie [Van Zandt], and the Warren brothers [Brett and Brad]. The first time I heard it, I loved it. I hate to say it, but it’s totally us. You know, our hair is turning white and we’ve always been red-blooded Americans, and rednecks.

It’s such a pretty song and such a great song to play. I always use a Gibson Les Paul or a Gibson SG. But on that song, I used Rickey’s Stratocaster because it just happened to be plugged in. It’s the only song I think I’ve ever played on a Strat.

Is that you playing the bird call at the end?

Yeah, at the very end, that’s me. I did that with a slide. I did it for “Freebird,” too. I turn the slide upside down and sort of hit the string with the side of the bottle and it just makes it sing.

What kind of slide do you use?

I use a Coricidan bottle I got from Duane Allman. He was one of my big inspirations. I just love him and I got to meet him and know him.

I always use glass because it has the best sound, more sustain, and it gets that true “scratchy” sound. I’ve got about a hundred of them.

What tuning did you use on the new record?

We play in standard tuning and Rickey uses dropped-D tuning. But on “Dead Man Walkin’,” we all tuned to open G. We wrote it on an old Dobro blues guitar, and that’s Rickey playing it.

With three guitar players in the band, how do you construct parts?

We think about it, and play off of each other. Once you’ve got one part, you don’t want somebody doing what you’re doing, so you’ve got to write a counterpart. We’ve been playing together so long that we know each other and what we’re going to do.

I’ll play my part then show it to Rickey or vice versa. Then he’ll come up with a counterpart to it that’s a little different. On “Lucky Man” there was enough rhythm going, so I just played slide. Same with “Red, White and Blue.”

You have to listen and write your own part. Then somebody else writes their part to you. In days before, I’ve written or thought of parts to go with my part. I’d show Allen or Ed King or one of those guys, but usually they all do it themselves. That’s why it’s a band.

When you get a band together instead of just studio cats or certain people, if you write a part or a song and then you go and present it to the band, everybody puts their parts to it. It just grows and grows. Sometimes it becomes a great song.

You must be really proud to be celebrating the 30th anniversary of the band.

Yes, I’m very proud of being a part of Skynyrd, from the old guys to the new. I know we’ve had a lot of tragedy and misfortune, but that’s just life.

What goals do you have for the future for both yourself and Lynyrd Skynyrd?

My plans and dreams are to keep going with Skynyrd – to tour every year and do a new album every couple of years, to show people we’ve still got it.

And I don’t ever want to do a farewell tour, where we say, “This is the last time,” and then we go back out again another time like a lot of groups do. There are a lot of groups that have “final toured” 10 times.

With Lynyrd Skynyrd, I want us to just not be there one day. I would like to tour for 10 or 20 more years, writing songs and getting on like the Rolling Stones, B.B. King, or Clapton. All the blues guys just keep on going, and I think we’ll do that. – Arlene R. Weiss

Vintage Guitar: Many people are surprised to learn you were originally a drummer for Lynyrd Skynyrd in the early ’70s.

Rickey Medlocke: Yes, I joined the band as a drummer and played for about three years. I’ve been back now since ’96, playing guitar. I knew in my heart that I would probably never achieve greatness as a drummer and that my talents lied within guitar and singing. I left Skynyrd so that I could play guitar, and as fate would have it, it’s all kind of worked out. The vicious cycle came around and here I am, back with them again!

Which players influenced you as a guitarist?

I was raised in a musical environment. My grandad, Shorty Medlocke, had his own bands and toured with musicians from Nashville and the southeast. He was even on a television show out of Jacksonville from 1953 through ’58. It was a cool schtick with a grandfather and grandson.

At the time I was playing banjo, which was my very first instrument. I had a miniature five-string and I played and sang with him until I was about eight years old. I started playing guitar when I was about five years old and guitar has always been my real love.

As a kid, I listened to records galore and radio stations back in the ’50s. I started listening to a lot of the early stuff like Elvis Presley when I was five or six years old. Of course, Carl Perkins played on some of the old Elvis Presley sessions, and I enjoyed him. He also played on a lot of sessions for Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, and people from the Sun Records label. My grandfather listened to a lot of old Mississippi Delta blues stuff, so I ended up listening to a lot of the old black players like Sun House, Robert Johnson, Mississippi John Hurt, and Leadbelly. It was like a Mississippi Delta blues/bluegrass/country environment. The blues was really my biggest influence getting into rock and roll, and I still love the blues.

By the mid ’60s I’d started listening to the Beatles. I loved them. Then I happened to hear a Jimi Hendrix record on a local radio station and I was just in awe of what was going on with the guitar and what he was playing.

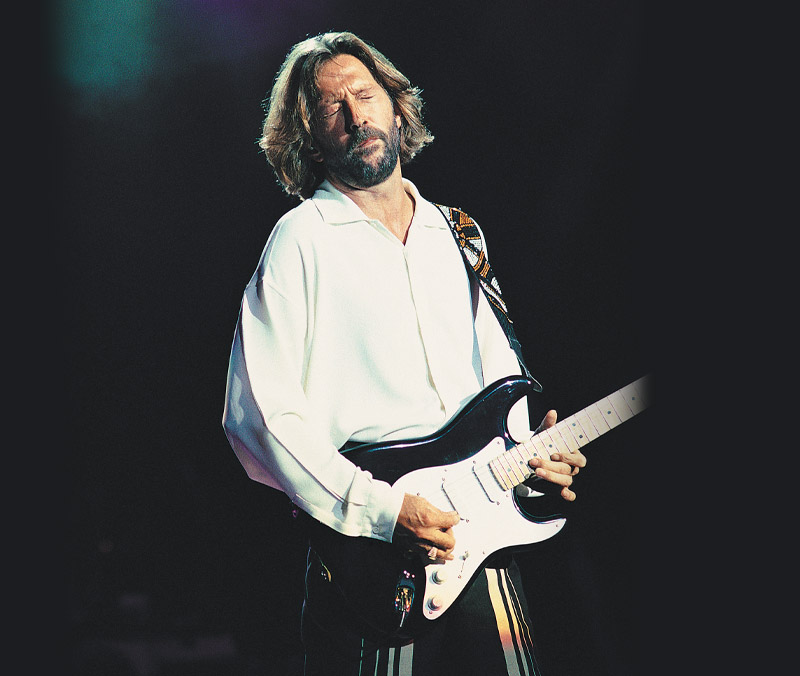

After that I followed Eric Clapton with Cream, then Jeff Beck with the Jeff Beck Group, and then Jimmy Page. In my teenage years, when I was learning how to play leads, my three favorite guitar players were definitely Hendrix, Clapton, and Beck. I still listen to those guys today. I’ve got some incredible footage of Beck playing live in Japan. His style and technique are just unbelievable. His tone is just… ahhh. You wonder what planet he came from.

I’ve always said that you bake the cake with Hendrix, Clapton, and Beck, but the icing is Billy Gibbons’ hands stuck on top. He’s always been a hero, as well as one of my dearest friends.

One of my best experiences was when we did the tour several years ago when ZZ Top and Skynyrd hooked up. My biggest thrill was getting to eat dinner at catering with Billy Gibbons and talk about cars, guitars, and music. I had the time of my life on that tour. I got to hang with Dusty, too, and he and I would take trips together. We went to the wrestling matches several times. It was just great camaraderie.

I’m also a huge Eric Johnson fanatic. He is a virtuoso. Sometimes when he’s playing guitar it’s like someone playing a violin. He’s just incredible. There are a lot of wonderful guitar players walking around – too numerous to mention. The world is full of talent, but to me those five guys are the cream of the crop.

Which players motivated your choices in gear?

Without a doubt, it was Clapton, Hendrix, and Beck. The combination of Gibson and Marshall together has always been my favorite. I’m still using an old Explorer and old Les Pauls. I do use a Stratocaster once in a while for certain songs, like “Sweet Home Alabama.” I like a Strat for the cleanliness and I use it for slide a lot of times.

Describe your live rig.

I’ve got an arsenal of guitars from the late ’50s right up through the late ’60s.

I love old guitars, and I don’t spare nothing being able to use them. I’ve taken some of my old guitars off the road, but Gibson has been wonderful enough to recreate a lot of my guitars in their Custom Shop.

I guess I’m a purist when it comes down to it, because I just love playing those old ones. I’ve still got my old Les Paul Black Beauty on the road with me and I just can’t turn it loose. I still love old Gibson PAF pickups and that’s what I love about the Seymour Duncan stuff. Seymour Duncan is the real deal. I have some ancient Seymour Duncan pickups loaded in a couple of my oldest guitars. I’ve never changed them out because they’ve never gone bad and as long as they’re still working, I’m gonna keep them there. In fact, the pickups in my black Les Paul are vintage JB models. They’re great. I basically use a lot of JBs, but I started using some other ones. I’ve got a couple of Pearly Gates in another Les Paul because for the density of the wood, they fit pretty well perfect.

For strings, I’m using a standard set of GHS .010s on most guitars. For guitars with dropped tuning, I’ll use a set of .011s. My picks are brass and they’re custom made for me by a guy named Len Milheim in Michigan. He’s got a die to cut them and he polishes and refines them like a teardrop. That’s how I get that metallic “squank” out of my strings. I’ll hold my pick with my thumb and forefinger and I’ll play with my index finger right next to it. This year I’m also using some transparent red heavy-gauge plastic picks by Dunlop that have my signature on them.

For the Vicious Cycle tour, I’ve got several old amps – hot-rodded ’70 and ’71 100-watt heads that I’ve been using for many years and an early JCM 800 head Jim Marshall gave to me when I was in Blackfoot. Skynyrd is sponsored by Peavey and I am using a Peavey straight cabinet. For effects, I use a Boss chorus and a Crybaby wah that was beefed up so it keeps the signal very steady so I don’t lose any volume.

How do you set the tone controls on your Marshall amps?

Usually, I like more beefiness and bass. I like running my bass at around 6 or 7 and I like running the mids at about 3. If you’re looking at it like a clock, I like running the bass at around 2 o’clock, dropping the mids back at about 10 o’clock, the presence is straight up between 12 and 1 o’clock, and the treble is at about 11 o’clock. The volume is another story. There aren’t enough numbers up there for me! But I’ll usually run the preamp at about 2 o’clock and the master volume at about 2 o’clock.

How does your live rig differ from the setup you used in the studio?

Well, actually it doesn’t differ a whole lot. I mean, 90 percent of the time what I play live is what I played in the studio. I love being able to recreate what I do live. I use Marshall amps, Gibson guitars, and once in a while a Stratocaster. I used a Stratocaster quite a bit on Vicious Cycle. But for the beefiness of the rhythm and a lot of the leads, I’m still a Gibson guy.

Do you take older guitars into the studio that you wouldn’t take on the road?

Absolutely. We fight with them a lot of times for tuning, but I’m just too much of a purist.

Not too long ago, I worked with a producer who was really a stickler on the tuning thing. I am, too, but he hated us having old guitars because they just didn’t tune properly. Get over it! I’m gonna use these freakin’ old guitars because they sound like nothing else in the world!

As a three-guitar band, how does Skynyrd separate things sonically and technically?

Well, each one of us has our own style, our own sound, our own tone. I have a real low-endy, beefy kind of tone, whereas Hughie has the single-coil Stratocaster sound, and Gary has a real nice smooth midrangey tone. You put it all together and it just blends great.

That’s the beauty of this band; we never fight over who’s going to play what leads in what songs because we just go with whoever’s style of lead playing fits whatever style of song it is. Actually, while we’re writing the songs, we start figuring out parts and who’s going to play where. Everything just comes together naturally.

Do you all work together when writing?

Oh, yeah. Gary, Johnny, Hughie and myself, we come in with ideas and then everybody starts adding their input. That’s how we come up it, lyrics and all.

How do you document the ideas?

There are usually one or two tape machines running, and we’re also jotting down notes and lyrics so we can review everything. We keep it all recorded and cataloged.

Do you ever demo the songs before making the record?

We have before, and we did demo some this time around to see how the basics would work out. But on other ones, we just went in and cut the basic tracks without making demos first.

Was the recording process for Vicious Cycle different in any way from previous studio experiences with Skynyrd?

Not really. It was approached the same way. Although for some of the songs, we recorded some of the tracks live and then went back and overdubbed our parts. We typically cut the basics and then go back and listen to everybody’s parts, then decide what should be replaced.

In general, we try to keep a natural feel to it. It’s really just standard procedure.

There are two tracks on the new CD now with Leon [Wilkeson] still on them. He played bass on “Lucky Man” and “The Way,” which we had started recording several years ago, before he died, and we were able to save the tracks. They made it onto the record, so we were able to put Leon on the CD one last time. It was very cool.

Where do you see the most change in yourself as a player?

I’ve been playing guitar for 48 years and I’ve become more seasoned. It’s just like good whiskey – it gets better over time.

I also find that I approach things nowadays from a slightly different side. I listen to the song. When you’re young, the song plays to you and you play your part. You want it to be great and you want to shine. As time goes on, you realize that the song doesn’t make you, you make the song. It’s what you put into it. My grandaddy Shorty always used to say you have to “kiss” it, which means “keep it simple, stupid!” Simplicity is the best policy. Honestly, that’s what the average person understands. They don’t understand that in four bars you played 25 notes. They just want to hear something that moves them and gives them chills – something they can relate to.

That’s what I believe, and I’d pass that advice onto everybody. – Lisa Sharken

Vintage Guitar: Who were your main influences in style and tone? How have those influences changed from early on to now?

Hughie Thomasson: Well, they’re constantly changing…

I started playing guitar when I was eight years old and first saw the Beatles not long after that. Of course, that influenced me and I started playing in a band when I was 12. We realized early on that we could work and do a lot more shows if we learned Beatles songs. Everyone loved the Beatles and a lot of the bands in the Tampa area, where I grew up, didn’t play Beatles songs. We did, so we got a lot more gigs than they did because of that.

We also learned that we could do three cover songs then put in one of our original songs, and get away with it. However, if you tried to play all of your originals, people wouldn’t like that very much.

In my teenage years, I went through a number of different bands. Dave & The Diamonds, was the first band I was in. Then we were the Rogues, then the Four Letter Words, and then finally the Outlaws.

Then from the Outlaws, I came to Skynyrd. So I’ve had quite the long playing career, you might say, and I’ve been very blessed to be a part of all of this.

A lot of the influences I’ve picked up on along the way were from Jimi Hendrix, Duane Allman, and a lot of people of the late ’60s, like the Byrds. We loved all kinds of music, so we played all kinds of music. I guess I’m kind of a hybrid guitar player. I love everything from classical to bluegrass. I actually grew up playing bluegrass with my family. So I’ve had many influences since I started.

Was guitar your first instrument?

Yes. Actually, I play steel guitar and banjo as well, but guitar is my main instrument.

Which players influenced your gear preferences?

Well, that’s Hendrix. I always liked the tone of his guitar – a Fender guitar. That’s what I use and that’s what I’ve always used. It’s my main guitar. I have other guitars, but I play a Fender. I do customize them to get the sound I want – I’ll change the tone pots, or add preamps, or change pickups. I have Seymour Duncan pickups in some of my guitars, EMGs in some, and Fender Noiseless pickups in others. I also have humbucking pickups in some.

There are lots of things you can do to change the tone of a guitar right down to moving your tone knob just one number and it changes everything. The amp settings affect the sound, as well.

So it’s a combination of things, and not just the guitar. I like a clean tone with a lot of sustain, and that’s what I’ve always tried to stick with. It seems to work with my style of playing and fits well with Gary and Rickey, who play Gibson guitars. My Fender is like the meat in the sandwich.

Tell us about your current live rig.

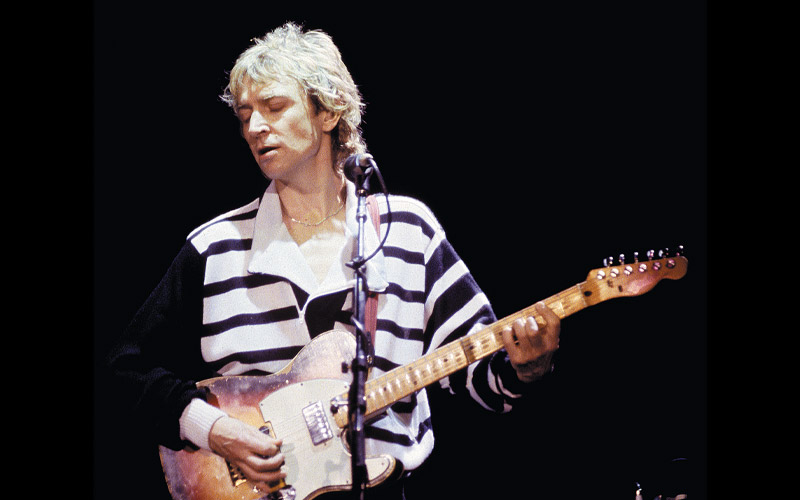

I’m using Fender guitars – mostly Stratocasters – and I have Teles, as well.

I carry a number of guitars with me, but I do have one Gibson, a Les Paul. As far as amps go, I use a Fender Super Twin and a Cyber-Twin, and a Peavey 100-watt Classic. I change the speakers in my cabinets, but I can’t tell you what those, are or I’d have to kill you!

I also have a couple of pedals by Boss – a Distortion and a tuner. I also have a wireless by Nady, and that’s about the extent of it. We keep it pretty simple when it comes to the gear. I think you get a better sound when you use less electronics. Less is more. You get a truer sound and a clearer signal. When you start putting other stuff inline, it weakens your signal from the guitar and it ends up changing before it gets to the amp.

How do you set the tone controls on your amplifiers?

It depends on the hall we’re in. We make minor adjustments according to each venue, so it’s always different. We try to maintain the same sound, but you do have to make adjustments to get back that sound from one building to another. We go in and do soundchecks, and my guitar tech has the basic settings down that we start from every day. We adjust from there until we get the sound that I’m used to having. I like a cleaner tone, so we use the preamp a little bit lower and the master a little bit higher. But everything is pretty much adjusted from 12 o’clock. We’ll go from there until we tune it into the room.

How are your guitars set up?

My guitars are set up with a .010 to .052 set and they’re set up pretty normal. I use Fender strings on some guitars and I use Dean Markley strings on other guitars. We just make sure that the guitar is in tune with itself, so that the intonation is correct on the guitar. We spend a lot of time checking that because if the guitar isn’t in tune with itself as you go up the neck, it will go out of tune on you and a lot of people don’t realize that. That’s why it sounds good when you’re playing down low on the neck, but as you travel up the neck, the guitar goes out of tune, and there’s nothing you can do about it once you’re playing.

So we’re very meticulous in making sure intonation is correct.

What type of picks do you prefer?

I use a standard medium plastic pick. One thing I do is I do sharpen the edges of the picks a little bit which gives the pick a little more bite. It allows you to turn the pick sideways and to attack the string with a different edge. Some people use sandpaper to sharpen it, but I take a knife and scrape it until it becomes almost serrated. I do it on all three sides. You have to be careful because it will actually cut you. I call them “sharpened” picks. That allows me to get a lot of the “pop” overtones and the overtones that you wouldn’t normally get from a rounded smooth pick. So that’s a little secret I just gave away!

Does your live rig differ from your setup on Vicious Cycle?

It doesn’t very much. However, because of all the advances in technology, in the studio we now have the option of using things like Line 6 Amp Farm for amp sounds. We did use that, but we mainly used the Cyber-Twin on a whole lot of the Vicious Cycle record. In fact, everybody in the band played through it at one time or another. We used whatever sounds best. You know, sometimes a smaller amp works better in the studio than your big rig that you use onstage. So we had a number of different rigs that we used – everything from a 15-watt Yamaha tube amp that I’ve had for about 20 years, all the way up to the Cyber-Twin, and everything in between. So it just depends on what you’re looking for that song, and the combination of the guitar and the amp to get the tone, sustain, and all the little things you’re looking for. Sometimes we would use a combination of Amp Farm and a mic’ed amp together to get the sound we were looking for. It’s tedious work sometimes. It’s really fine tuning. That’s the hard part. You get close, but you’re not there and you have to take the time to really dial it in. And you’ve got to have good ears. One thing that I found out in the studio is if you spend too much time listening to yourself or listening to the work that you’re doing too loud, you will burn your ears out and you will not hear good. So therefore, you’re never going to hear what you’re looking for – your true tone. So it’s a combination of whatever sounds best.

Do you have a preference for older or newer gear?

I prefer the newer gear. I have some older guitars like my ’72 Strat that I used on the Outlaws (Arista, 1975) record. I recorded “Green Grass and High Tides” and all those songs with it. Other than that, I don’t have many vintage guitars. I kind of go through them. I play them so hard that I end up having to re-fret them a lot.

Every year or so I have to re-fret all my guitars. I’m pretty hard on them. I have a light touch, but when you play the same songs during a show like we do, and you play over and over in the same position, it has a tendency to wear those frets down in the same place. When that happens, the guitar doesn’t play well in other places down the neck. So we’re constantly working on them, keeping them fresh and ready to rock.

Nobody wants to mess with an old vintage guitar. I think if you change a saddle or pot, or anything on it, that’s going to change the sound of the guitar. And when it comes time to working on them, I don’t know. That’s why I prefer new guitars. I have guitars going back, six, eight or 10 years, but those aren’t vintage guitars in my book. I have a tendency to stay with the newer stuff and go with the modifications that I need to make them sound the way I like them to sound.

I don’t have many older guitars. I just seem to wear them out, then refurbish them and keep them. I’ve got some nice Gibson acoustics that are vintage. I couldn’t even tell you the model number on the oldest one because there’s not one on it. There’s a stamp on the inside, but I don’t recall what it is. It’s somewhere in the neighborhood of about 35 years old. I also have a rare, very old Emmons pedal steel guitar that was given to me by Toy Caldwell of the Marshall Tucker Band.

I do have quite a collection of amps. I’ve got everything from a ’65 Fender Bassman all the way up the Cyber-Twin. I have a bunch of different Fender amps including a ’65 Super Twin, two Peavey 100-watt Classics, and a 15-watt Yamaha. I did part of the Ghost Riders… (Outlaws, 1980) record with that amp. We just put a very expensive microphone on it and it sounded like a million dollars.

What advice would you give to other players on developing their tone?

Just keep searching and playing and trying new things, and when you hear it, you’ll know it.

But you shouldn’t be satisfied with it being just okay. It’s got to be you – you’ve got to feel it, you’ve got to know it, and it’s got to work for you. When you hit that note and it sustains just right, then you know you’re there. Sometimes guys never find that and sometimes they find it straight away. Everybody’s different and it depends on how much time you’re willing to put into it.

Like I’ve always said, you get out of it what you put into it. If you spend a lot of time working on it, then you’re going to end up getting the sound you want.

One of my favorite guitar players is Eric Johnson. He has an enormous amount of tones and sounds, and I know for a fact he spends a tremendous amount of time meticulously going through every aspect of his equipment. That’s what you have to do if you want to develop your own sound. You really have to spend the time.

What advice would you give on playing in a multi-guitar band?

It’s difficult with three guitars, like we have with Lynyrd Skynyrd and did with the Outlaws, as well.

It’s extremely difficult to hear each guitar while the whole band is playing and know who is playing what. It’s something we are constantly aware of and working on, and it’s not an easy task.

If you have the right combination of people willing to work together and compromise, then you can get there. The three guitar players in this band work together very well, as does the whole band. We all have an opinion, but we don’t force it on each other. We wait and we try to help each other, and do what’s best for the band – what makes it sound like Skynyrd the most. – Lisa Sharken

This article originally appeared in VG‘s October 2003 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

In Episdoe 23 of “Have Guitar Will Travel,” host James Patrick Regan speaks with singer/songwriter/A-list session guitarist Jedd Hughes. A veteran of the Nashville scene, Hughes grew up in Australia before seeking musical stardom in the U.S. Here, he talks about his long, sometimes rocky, but successful road, including backing Patti Loveless, Rodney Crowell, Emmylou Harris, and Vince Gill, as well as his solo career and new album, “West.”

In Episdoe 23 of “Have Guitar Will Travel,” host James Patrick Regan speaks with singer/songwriter/A-list session guitarist Jedd Hughes. A veteran of the Nashville scene, Hughes grew up in Australia before seeking musical stardom in the U.S. Here, he talks about his long, sometimes rocky, but successful road, including backing Patti Loveless, Rodney Crowell, Emmylou Harris, and Vince Gill, as well as his solo career and new album, “West.”Each episode is available on Apple Podcast, Stitcher, iheartradio, Tune In, Google Play Music, and Spotify!

Have Guitar Will Travel, hosted by James Patrick Regan, otherwise known as Jimmy from the Deadlies, is presented by Vintage Guitar magazine, the destination for guitar enthusiasts. Podcast episodes feature guitar players, builders, dealers and more – all with great experiences to share! Find all podcasts at www.vintageguitar.com/category/podcasts.

But it is true that when Rod Price’s slide hand is in action, it isn’t easy to capture on film – as fans of guitarist and the legendary English band, Foghat, can attest. When Price straps on his modified late-’50s Gibson Les Paul Jr., he becomes one of the best slide players in the business.

And if there’s a commonality between the man, his playing, and his music, it’s that they are all “open;” Price plays slide guitar exclusively in the key of open E, the title of his first solo album is Open (Burnside Records), and then there’s the candid manner in which he discussed his musical history and personal travails in his first real interview since the death of Foghat bandmate Lonesome Dave Peverett (VG, December ’91) in February of 1999.

Vintage Guitar: You were born in London, in 1947. Did you come from a musical family?

Rod Price: Yeah; my father was deeply into classical music, as was my older brother. The radio was also on continuously, so I got a diverse listening experience. I’d heard things on the radio like Roy Rogers’ “Four Legged Friend,” when I was a child, and I’d say to myself, “That’s not it.” It was really bizarre, because I didn’t even know what I was looking for. Then one day I heard Big Bill Broonzy, and I said, “What the heck is that? That’s what I’ve been looking for!” It was an epiphany – a spiritual experience – from hearing an E7 chord. In my world, nobody had ever added a seventh to a major chord.

Was the Broonzy song on the BBC, or Radio Luxembourg?

BBC, probably around ’59. Radio Luxembourg didn’t really happen until a little later. So Big Bill Broonzy albums were the first records I got. I played those for years; he was a wonderful guitar player, and I adored his voice. His singing sounded warm, silky, and fatherly. I was sold; I knew what I wanted to do.

After that, I got a country blues album that had artists like Leroy Carr, Scrapper Blackwell, and Robert Johnson on it. There was a store in London where everybody used to go to get their blues and jazz albums; a wonderful, dusty old place called Dorbel’s, which closed a few years ago, and what was great about the albums is you could get a lot of clues about the music from the liner notes.

One of my earliest influences was Tampa Red, probably because he was one of the first guys who played single-note slide. But as far as I’m concerned, Scrapper Blackwell – the guitarist with Leroy Carr – was the man, he did some solo stuff in the ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s, and some wonderful person found him in Indiana in the ’60s and recorded him yet again. Blackwell is truly one of the most underrated players in history; his stuff sounded like Robert Johnson before Robert Johnson came on the scene. He wrote songs like “How Long” and “Blues Before Sunrise.” If you ever get to hear him, you’ll be knocked on your ass because you won’t believe what you’re hearing.

He was part Cherokee Indian, and he’s now gone – and it pisses me off that he was mugged and murdered when he was an old man. I was about 15 when I first heard him, and he blew me away more than any other guitar player I’ve ever heard.

I went through the rock and roll thing as well; the Shadows, Eddie Cochran – in fact, on my next album, I’m doing one of Eddie Cochran’s instrumentals.

It sounds like your early interest in the blues came full-circle on Open, which sounds like purist Chicago-type blues instead of earlier country blues…and it certainly doesn’t sound like blues/rock or heavy blues.

Absolutely, and I’m glad you clarified that. I could’ve done an album of all-original stuff, but I’d started with [Graham “Shakey Vick” Vickery] back in ’65, and I wanted to pay him back.

Were you not as interested in rock and roll and Radio Luxembourg as others might have been, due to your dedication to purist blues?

It helped; I needed rock and roll to help become aware of players like Buddy Guy, who I didn’t even know existed; I’d grown up listening to country blues. But I didn’t have a big record collection; in my mind, the blues had already engulfed me, so pop and rock and roll were kind of meaningless.

Did you take any formal guitar lessons?

I played for about a year on my own, and then told myself I’d like to know what I was doing. I left school at 15; they wouldn’t allow me in the musical appreciation society because I was one grade below. I took what were “music lessons” more than “guitar lessons,” including music theory, and I started listening to Davey Graham, a wonderful player who did an eclectic mix of blues, folk, and jazz. I played some of his songs for my music teacher, who said it was crap, so that was the day I left (laughs)!

Tell me about some of your earliest instruments.

The first one was some sunburst no-name thing with f-holes. I had a couple of Höfners, and the first good electric I had was a Gibson Melody Maker, which I used with Shakey Vick’s Big City Blues Band and Dynaflow Blues. I thought I was following Eric Clapton and Keith Richards down their “guitar roads,” but I didn’t realize they had more than one guitar! I’d see Richards with something like an Epiphone, and the next time I saw him, he was playing something else. I went through a period playing a Tele, which was mainly from seeing Clapton in the Yardbirds. Then I tried Strats. When I was in those two bands, we worked a lot because we’d open our own clubs. It was a great time to experiment with guitars and get your chops together.

When did you start concentrating on slide guitar and open tunings?

When I heard Robert Johnson, I told myself I’d never get that good, but I thought it might sound interesting on electric guitar, and that was before I heard Elmore James. Then there was a plethora of other influences; believe it or not, the first person I ever heard play electric slide live was (the Rolling Stones’) Brian Jones.

I went home and got an old piece of brass tubing, and found I could be far more expressive in my playing. I remember thinking, “If I can get this down, I’ll be a much better player,” but I put it aside for a while. I didn’t really begin concentrating on it again until I could afford more than one guitar. When I first got with Foghat, I only had one guitar, so on the first album I played in regular tuning. I also played in regular tuning on the second album, but I’d bought a new guitar, so after that album I started concentrating on slide in open E. I don’t know why I chose it; there were very few books around. I might have gotten it from Elmore James, although I think he tuned down to D a lot. That’s the only open tuning I’ve used.

Details about your “pre-Foghat” bands?

When I was 17, a friend told me he had a band for me; they were doing Elvis Presley, rock and roll stuff. I didn’t know if I was ready, but I did it for three or four months, just for the experience. Then I went to the old, reliable Melody Maker, by that time, I was hitting the blues clubs in London, checking out Clapton and others. The magic of those times is indescribable. There were times when you could see American blues musicians like Bukka White, Little Walter, and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee, all on the same bill! And I’m sure people like Eric Clapton and Peter Green would have been in those audiences, too. We were totally engrossed in this American music that had so much feeling and was so true and real. I wasn’t interested in something like psychedelic music at all.

I was an original member of Shakey Vick’s band, but I was the last guy to come onboard. I found out by reading Melody Maker that they were looking for a guitar player, went for the audition, and got the job. Graham (Shakey Vick) really knew about all of this wonderful music, so that was when my education really began. The first rehearsal I did, [Savoy Brown singer] Chris Youlden was there. It turned out Graham and Chris co-owned a Robert Johnson album, a Blind Boy Fuller album, and one other, and each week when we had rehearsal, I’d steal one of ’em to listen to (chuckles). I’d replace it the next week, but steal another one.

Chris used to sit in with the band, and we couldn’t play very well, but we had feeling and raw emotion. Dave Peverett sat in with us, as well – he’d met Shakey and Chris years before I did. We also got to play with Champion Jack Dupree, which was a big thrill, of course.

How did the Dynaflow Blues band differ from the Shakey Vick band?

Well, Shakey Vick (laughs)…one time when at a Tuesday night gig, we asked Graham about the money from Saturday night, and he said, “Well, I spent it on the horses.” So we said, “Screw this,” but Graham and I still can have a good laugh about it, and he doesn’t mind me telling that story. We formed Dynaflow Blues with another harp player, and that lasted for about a year. The original harp player went off to college, and I was in a music store one day, and ran into Duster Bennett, who was a one-man band we had seen with Fleetwood Mac. He played kick drum, hi-hat, guitar, and harp. He did a few gigs with Dynaflow, but I’d go to his house to learn. He bought a cheap Harmony from me just so I could get a better guitar. He was a real sweetheart; he was killed in a car wreck in 1976. I thought he was the best harp player in England. My next album is dedicated to him.

Black Cats Bones came after that, and definitely wasn’t a purist blues band. The Barbed Wire Sandwich album was heavy blues/rock.

It was, and that’s where Paul Kossoff and Simon Kirke were before Free. I did that for about a year also, and didn’t get much out of it.

By that time, what instruments and amps were you using?

Prior to that, I was using a Vox AC-30 with Shakey Vick and Dynaflow, and a Tele, for the most part. I was playing a Strat in Black Cat Bones, through an Orange amp; they had just come out.

I played with some other folks for about a year, but we never really gigged. It was, however, a year of learning for me. We had jams that went all night; a lot of them were based on the stuff Sugarcane Harris did with Frank Zappa. Although it wasn’t what I wanted to do, it was great to jam on it. That band broke up, and blues was actually waning a little bit around that time, 1970 or ’71.

One day, I looked in the Melody Maker, and an ad said, “Wanted: Blues guitarist/pianist for blues band.” I made the call – although I wasn’t a pianist and spoke with a gentleman for a long time; he was being very secretive, and eventually I said, “Dave? Is that you?”

Peverett?

Yeah, and he said, “Rod? Is that you?” (laughs). Three of the members of Savoy Brown were forming their own band, and even though we had already jammed together back in Shakey Vick, I still had to do the audition. I was kind of surprised I got the gig, because there were some great players there.

Who played which guitar part on the call-and-respond intro to “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” on Foghat’s first album?

(chuckles) Dave did the first one, I did the second – where the note kind of bends down. That was a new black Strat through a Hiwatt.

What do you think caused Foghat to break away from other bands back then?

(pauses) Incessant touring certainly helped. I think we had a good foundation with our dedication to the blues, and we played with every ounce of emotion and energy we had. Pure, raw excitement and energy. We wanted to play, and I think if you’ve got that attitude, you’ve got a better chance of making it. None of us ever said anything like, “Wow, wouldn’t it be great to have a gold album,” or “Wouldn’t it be great to work $20,000 gigs;” we would talk about how we could do a Willie Dixon song we liked. I think it was actually a type of innocence that gave us that edge, plus just a passion for music.

A lot of players cite the band’s ’77 live album, which ends with a rave-up version of “Slow Ride.” Your slide guitar is shrieking on that track…

The album does seem a solid favorite; I think it captures the essence of what was going on. During that period, I was using a Sunn Model T 100-watt amp, an SG for slide, and a Les Paul for regular lead.

Any memorable gigs you’d want to cite?

Actually the most memorable experience wasn’t a gig; it was having dinner at Willie Dixon’s house. Around ’76 or ’77, we were in Chicago, and Shirley, his daughter, came down to the first show, and the next night, Willie came down. We were going to be based out of Chicago for a few weeks, and he invited us for dinner. It was probably the most special evening of my life. He was so humble and kind; he said, “I know what it’s like being on the road – you boys need a real good home-cooked meal.” We had a big roast, and were stuffed! That was when he’d just had his leg amputated, and his son was telling him he was needing to watch his weight. Willie looked down at his stomach and said, “I’m watchin’ it, son” (laughs). We talked about his record royalties and he pulled out all of these old 78s we were drooling over. He noted that regarding royalties, “You guys paid me,” and I think he was grateful that we hadn’t done what some others did. He really liked our version of “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” and I was really touched. Dave and I had dinner with his daughter a couple of years after he’d passed away, and she told us Willie always asked about us.

In the convoluted history of Foghat’s personnel changes, you departed on more than one occasion.

I’ll be glad to tell you the whole story. Around the time we did the Stone Blue album, I was exhausted. We’d been touring constantly, and the album was a struggle to get done correctly. I remember lying on the floor in my house, asking myself, “Why am I doing this?” I had a nervous breakdown, and one thing that made it more sickening was when I walked in the Foghat office one afternoon before we had to leave for a show that evening, and I collapsed on the floor.

The doctor came over and said I’d had a very severe anxiety attack; my body was telling me to stop. The doctor said, “I want Rod in the hospital right now. He’s exhausted, he’s dehydrated, he’s shot.” And I remember the manager saying, “We’ve got a gig tonight,” so he took me down to a local bar, got me a couple of shots, and put me on a plane. That was really the beginning of the end.

I made it through the recording of Boogie Motel, and I was drinking way too heavily, but I thought of it as self-medication. I went to a lot of doctors, trying to find out what was wrong with me, and this was at a time when nobody really knew much about anxiety and panic attacks. I was looking for help and I couldn’t get it. Specialists would go through me and couldn’t find anything wrong.

All I wanted to do on the road was play, then go to my room with some alcohol and leave the planet for awhile. I don’t mind talking about it, because I think it’s important for your readers to understand what happened. The point is, the rest of the band seemed to be riding the wave okay, but I was taking my soul, cutting it open, and showing it to everybody else. I did that onstage every night, and I realized later that I couldn’t do it for five months at a time.

I wasn’t that involved with Boogie Motel, and I wasn’t that happy with the direction of the music. There were problems with producers, and it seemed everyone was getting tired. What I didn’t realize, until recently, is that I wanted the band to fire me, and they did. I was gone in early 1980.

I shut down in the ’80s, and was pretty lost. I’ve found out since that I had clinical depression, which is why I was trying to self-medicate. It took a long time for the medical arts to catch up with what I had, as many people have found out.

At one point, there were two versions of Foghat, one fronted by Peverett that was based in Orlando, and one featuring (drummer) Roger Earl that was handled by a PR company out of New Hampshire. You had an association with Peverett’s version in the early ’90s.

I went to England to visit my parents, and one of the people I spent time with was Colin Earl, Roger’s brother. I was feeling a little better, and told Colin I wanted to get in touch with Dave, because we’d split up, but had never really talked about what happened. Colin told me Dave was living in Orlando, so when I got back to the States, I called; I didn’t think any problem should have destroyed our friendship; we’d spent 10 years on the road together making some great music. I had no plans on getting back together with Dave. I spoke with his wife, and Dave called the next day; he was out on the road with his Foghat. We had a wonderful talk. Before you knew it, we were discussing Robert Johnson and Elmore James.

He came to Boston about a week later, and asked me to come sit in with the band. I’d started to play again, and was doing some demos. When I played with Dave, he told me I was better than I used to be, and asked me to join the band. He also had a guitar player named Brian with him, and didn’t want to let him go. I toured for a little while with them, but three guitars were too much. We did a tour in Germany with Molly Hatchet that was actually one of the most enjoyable times I ever had with Dave, but when we came back, I was still tired and still depressed, but I didn’t know it, and that’s when I left again.

I don’t know what happened with Roger going out as Foghat; I understand that at one point, Roger had wanted to use the name of one of our publishing companies, but I really wasn’t around.

When did you finally get in the clear, health-wise?

Not until three years ago, when I truly found the right doctor. I’d put on a great deal of weight and my M.D. decided, after I’d tried just about everything, that I should try Prozac. I said, “I’m not depressed” – or so I thought – but he said it would help cut my appetite. I started taking it, and for the first time in my life, I felt normal. You’ve probably heard a lot of nightmares stories about that drug, but the truth is that it was one of the first really good drugs for depression. Then I got on another prescription called Paxil, which totally saved my life, my marriage, everything. At that point, I’d started working out, and the irony was that when I really started feeling better for good, the band (Foghat) was back together.

And this time, it was the original foursome.

(Producer) Rick Rubin wanted to put the band back together, but he was also in the middle of recording an album with Johnny Cash. Rick got in touch with our old manager, and ultimately we didn’t end up recording with Rick; we recorded for Paul Fiskett, who had been president of Bearsville Records, and who now had Modern Records, Stevie Nicks’ label.

Were you satisfied with the way Return of the Boogie Men and the live album recorded in the mid ’90s turned out?

No, and let’s take one at a time: I thought Return of the Boogie Men was a wonderful opportunity for Dave and me, because we’d gathered a great deal of material independently. So when we got together, writing the album took 10 minutes (chuckles)! Dave and I believed we should have waited on Rick, but we were coerced into this other deal, and the other producer only had a certain amount of time to work with us, because he had other projects. So to a certain extent, we were rushed; however I do believe that some of our later best work is on that album.

When the Boogie Men album came out, I said I thought we should do another live album, and a video of it. At a meeting early in the tour, I said we should do it within a month, because by that time we would’ve gotten the cobwebs off and would’ve started to get hot. But as a tour goes on, you tend to get a little tired. Unfortunately, due to finances, we couldn’t do it ’til the end of the tour, so we were a little exhausted. A lot of the material we wanted on the live album didn’t end up on it. It was okay, but…

Do you still prefer the mid-’70s live album?

I never listen to them. It’s funny; whenever I do something and get it done, I go on to the next thing.

Do you feel like talking about Lonesome Dave’s passing?

Another bit of irony is that when I started getting my head really clear, I told myself that I didn’t think I could record and tour like that for another five, 10 years – that’s what they were talking about doing. I had two other projects I wanted to do; one was the blues album, and the other was the next album I’ll be doing.

We were taking a break, and Dave’s wife got ill, then Dave got ill. It was truly a dark time. I have a five-year-old son – my only child – and the thought of leaving him at home and not educating him in the ways of the world was too much for me. My wife is a very caring and loving woman, and she’s put up with a lot of crap over the years. It was a horrible time to leave the band, but the point is, there was never a good time to do so.

Being on the road can take a lot of the important parts of your life away from you. My son totally changed my life, and I think my music has actually improved since he was born; by giving, you get. Dave and I had talked about doing a blues album together, but it never came to pass because Dave was happy doing the Foghat thing, and he had in fact done a lot of recordings I think will eventually be released.

I spoke to Dave, basically telling him, “I don’t want to bother you with this while you’re ill, but I’ve got to take care of my family.” The good thing is there were no hard feelings; we talked a time or two afterwards.

One Sunday night, I was at (producer) Tom Dawes’ studio, putting the finishing touches on the Open album. I’d spoken to Dave about a week before, and he wanted a copy of the album. That night, my wife called and said there’d been a call from Orlando; that Dave had been told by the doctors that he only had about six weeks to live. So that night, I left New York and drove back to New Hampshire; the next morning my wife woke me to say he’d already passed away; he didn’t have six weeks after all.

What can you say? It was unexpected, because he’d been fighting it for a while.

So now, you’ve come full circle in more ways than one – back to Chicago-type blues, with Graham Vickery once again. Some will hear it and say it’s authentic, but with an English interpretation.

It’s got that type of edge, and I think it represents a part of me that was always there.

I never wanted, for example, to perfectly copy an Elmore James solo. But I wanted to do everything I could with his spirit. Some people said the album has too many covers, but I don’t like that word because I was paying tribute and homage to all of these wonderful people who’ve inspired me my entire life. One of the things I hoped is that the money for the writers of those songs will get to their families. Their music has kept me alive all these years.

Any personal favorites on the album?

“Sittin’ On Top Of The World.”

…which is an instrumental version of the Howlin’ Wolf song…

I’ve always wanted to do an instrumental version of it, to show people where it came from. I think it’s one of the most beautiful melodies in the world. The band was real hot, and we had no rehearsals

“Sittin’ On Top Of The World” is my personal favorite, but I wanted to take all of the songs Graham knew inside out, and I wanted people to know what I used to do 35 years ago.

The slide guitar on “Sittin’ On Top Of The World” gets so high up, some might think it’s a lapsteel.

(chuckles) That’s the highest I’ve ever been on a slide. I remember after the take, Tom Dawes said, “Hey Rod, I think you were a little flat on that last note,” and I said, “Listen, there’s no room between the pick and the slide! Whaddaya want me to do?”

The great thing about Tom, though – he produced (Foghat’s) Rock and Roll and Energized – is he really lets me go, but makes sure I don’t stray, y’know? He’s a gentleman and a wonderful all-around musician. I’m grateful we rekindled our friendship; he gave me a great deal of guidance.

You brought a highly-modified double-cutaway Les Paul to a Texas guitar show some years ago, and that appears to be the same one in your current publicity photo.

Greg Morgan has been my guitar tech for years, and back when I was using that SG (with Foghat), we had Grovers (tuning keys) on it, and they can tend to pull the neck down a bit due to their weight. When I’m playing slide, I don’t hold onto the neck very much, and that SG was too top-heavy. We even tried altering the strap, but it wasn’t working. He told me to try Dave’s guitar; Dave, as you know, always played Juniors. I liked the way it felt, so when we were in Nashville, Greg picked out a beat up Les Paul Jr., and basically rebuilt the entire thing. He re-routed, re-fretted it, and painted it. When I got it, I’d never played another guitar like it. It has two PAF humbuckers; I like their warmth, and I feel like the slide is my voice, so those pickups help.

You see, when I used to take solos in the early days, I used to sing different lyrics to myself while I was playing the guitar, and that was how my slide playing developed.

Did you use any other guitars on the album?

That’s a ’62 reissue Strat on “Elevator Woman,” and it’s got Texas Special pickups. I also used an SRV Strat, but that Junior has been my main guitar for many years. What’s interesting is that I don’t play it whenever I’m just sitting around, but when I get onstage, I have to have that guitar. I’m not a big collector, and as the Junior pretty much defines my voice, I follow the saying about “If it ain’t broke…” The only thing I’m needing in my collection in a good dobro, and Liberty Guitars makes some magnificent ones, so I may get one of those. Otherwise, I’m happy with what I’ve got.

What about current amps?

I’m using Soldano. I’ve got one made for me without reverb, it’s like one of their Atomic models, but it’s set up like a (Fender) Twin, which tells you something about wattage – it’s totally irrelevant. This thing is an absolute gem. Mike is really into his amplifiers, and they’re magnificent. He’s one of the nicest guys I’ve met.

It sounds like you’ve become more of a homebody – and for good reason – but players usually do have to tour to support a new album.

I will be touring, but in a modified way. I prefer to play clubs, and I love to meet the fans. I’ll be playing on a permanent basis on the New England circuit, including New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. I’ll also be going to Chicago and the West Coast, but I just won’t be doing incredibly long tours. Playing live is still the joy of my life.

This is almost a philosophical finale given the type of music you love; do you think it’s possible, these days, to write new, purist blues music?

Well, the next album I’m doing is still very blues-based, but not necessarily in I/IV/V songs. I would not want to do another Open, although I’m very happy I did that album, of course. On the next one, I’ll be singing some of the songs myself, and there will be horns on some of the tracks. I’ll be doing a few covers, but I’ve already written more new songs. I think it’s the next natural step for me, and to explain that verbally would be very hard (laughs). All I want to do is be a better player.

Price’s conversation about his musical and personal history didn’t pull any punches, nor does his guitar playing. The legendary guitarist now knows his priorities in all facets of life, and looks forward to making his own music on his own terms. He has certainly earned the opportunity.

This article originally appeared in VG June and July 2001 issues. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.