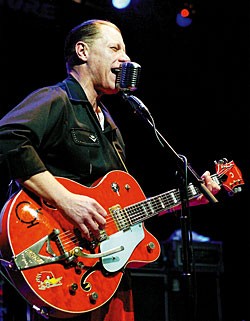

Photo: Brian Blauser

Experiencing a Tommy Emmanuel performance is one of those “You-shoulda-been-there” musical epiphanies. Emmanuel strides onstage with his acoustic guitar, displaying a self-assured countenance under his widow’s peak, and proceeds to mesmerize.

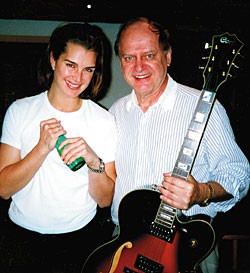

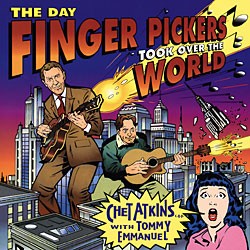

The Australian is also one of the privileged few pickers who recorded a duo album with the legendary Chet Atkins; their 1997 Columbia release, The Day Finger Pickers Took Over The World, was nominated for a Grammy. Being an Atkins protegé is just one of the many facets of Emmanuel’s decades-long career, and when VG caught up with him, he was in the middle of a tour, anxious to talk about the release of his first true solo album, Only, on Steve Vai’s Favored Nations label.

Vintage Guitar: Your earliest musical efforts involved playing in a family band.

Tommy Emmanuel: The first music I remember listening to would have been Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Snow, and some traditional Australian country singers. The Shadows were big, we listened to them, the Ventures, Duane Eddy, and some traditional Hawaiian music, as well. Merle Travis and Joe Maphis were high on our list, but it was hard to get that kind of music in Australia. My brothers, sisters, and mom and dad and I were all music nuts; we loved to play and learn.

I heard Chet when I was seven years old, and that kind of changed the course of my whole life. I was happy being the rhythm player in a band – my brother played lead – and when I heard that sound, it blew my mind. I could hear what was going on; I just didn’t know how to do it. But I kept at it, and eventually worked it out. Chet was not only an influence, he was a person who set a standard for you to look up to – in playing, sound, recording, quality of melody.

Did hearing Chet make you want to play more acoustic, even at that age?

Well, I wasn’t really aware of much difference; it was just guitar! It was a little later in life that I got into acoustic, but I’ve played electric all the time, and I still play electric a bit, but not much on tour.

I’ve still got my first electric guitar, an Australian-made instrument called a Maton, and I still play Maton acoustics on the road. I’m not an endorser, but I play their guitars, and they sound great. I’m a big fan of Martins, Gibsons, and Larivees, but at the moment I can’t travel with many of my guitars – I do have some wonderful Taylors, too – but I’m on tour all the time, and I take Matons out with me. You can play cricket with ’em (laughs)! They hold up very well.

Who played what in your family band?

My oldest brother, Chris, was on drums, my sister, Virginia, played Hawaiian steel guitar, my brother, Phil, was on lead, and I played rhythm and bass. I wasn’t so aware of bass guitar; I was kind of playing bass and rhythm at the same time. We formed the band in 1960, and it wasn’t until a couple of years down the road when we were playing a show with a bunch of other bands that I saw something onstage in the band that came on after us, and I asked my brother, “What’s that other guitar up there?,” and he said, “I don’t know; it’s only got four strings!” That was the first time I’d really noticed what a bass guitar was.

Emmanuel poses with his mentor, Chet Atkins, in 1997, the year their collaboration album, The Day Finger Pickers Took Over the World, was released.

You established yourself in Australian sessions before you achieved international acclaim.

Between 1975 and 1990, I played on an enormous amount of records and film soundtracks; people like Air Supply, Roberta Flack, and a lot of Australian bands. I was was offered the soundtrack to the Crocodile Dundee film – the first one – but I turned it down because I didn’t think it would get off the ground. In hindsight, what a fool I was (chuckles).

Is it fair to say you established yourself in most of the world’s markets, and the U.S. is the last “frontier?”

I think America, England, and Germany are the new frontiers for me, because I’ve done a lot in Australia and Asia, and things are building well.

I’m really just getting going (in the U.S.); it takes time, and you have to keep coming back. I think getting the Only album out on Favored Nations is gonna take things up to a new level.

Describe how you eventually met and began your musical association with Chet Atkins.

I had been writing to Chet since my dad died. As I said, I just about lived inside (Chet’s) albums; that was my whole world. As I found out once I got to know him well, he would listen to people from around the world, and would want to know what they were doing. People who were from Australia that went to the States would take him my tapes. He was fascinated by his influence on people so far away.

In 1980, I finally got to make the trip to Nashville; we met in person and played. We had a great time. By ’88, I’d had enough of playing on everybody else’s albums, and I started my solo career. I got a tour with John Denver in ’88 that kind of “launched” me into the public. The musicians knew me, but when the public discovered what I did, it appealed to them. I’m always out there playing for the people, anyway, and I think that’s another reason I got so much studio work – because I didn’t approach a session like a studio player; I approached it like a real performance; what was right for the track.

Was James Burton the guitarist for Denver at the time?

Yeah, and that’s somebody else who taught us so much. All those old Ricky Nelson and Elvis records; we all bought them and learned from them. Jerry Scheff was with John Denver then, too. I saw them, along with Glen Hardin and Ronnie Tutt – the “Elvis” tour – boy, did they play great!

The Day Finger Pickers Took Over the World

Was The Day Finger Pickers Took Over The World the first time you’d recorded with Atkins?

No, the first thing we recorded together was in ’93, on my album The Journey; a track called “Villa Anita.” From that time on, we started to get close, like family. Every time I came to Nashville, he’d invite me up to his house, and I ended up staying because he had kind of a “granny flat” on the side. I’d get up early in the morning, come up to the kitchen and sit with him and (Atkins’ wife) Leona, and we’d start playing.

Details about The Day Finger Pickers Took Over The World?

We both wrote for the album, and wanted to do “Waltzing Matilda,” the famous Australian song. I wrote a song on there called “Mr. Guitar,” which is dedicated to him, and another original of mine on there is “Dixie McGuire.” We did an arrangement of a tune called “Borsolino,” which is from an Italian movie. We sing together on “The Day Finger Pickers Took Over The World,” and there are a couple of comedy songs; “Mel Bay” is kind of a spoof about how we’re two guys who bought Mel Bay’s books.

Other exciting times with other notable players besides Chet?

I was the opening act for Eric Clapton on an Australian tour, and he was very nice to me. I’ve toured with Tina Turner and Michael Bolton.

Has any of your live material ever been released on CD?

I’m sure there are live albums all over the world, but there’s no label on them (laughs)!

How many Chet Atkins Appreciation Society conventions have you attended?

Every one since 1996.

One of your more exciting numbers, as performed at that organization’s closing concert in 1997, is “Initiation,” which you announced was inspired by an Aboriginal ritual. The song included use echo and percussion effects you play on the guitar body. Tell us about how you set things up for that song.

The song is a piece of musical drama; it’s supposed to be telling the story of the ritual where a boy proves himself to be a man. It takes time, and he has to go through all sorts of tests; they circumcise him with a rock, cut him, burn him, and leave him out where he has to survive. I try to create an atmosphere using the body of the guitar, and I try to create sound effects that add to the storyline.

I use extreme EQ on it; exagerrated midrange and bottom-end. That’s the way you get those sounds, but if you bang on (the guitar) too hard, you’ll break speakers, so I have to be real careful at the same time. I use digital delay, and the sound man at the front puts some long reverb on it; about four seconds. And I crank everything up until it’s almost in the red. While that’s going on with all of those noises that are supposed sound like wind, rain, thunder, and animal sounds.

The band, 1963. Left to right, Tommy, Phil, Virginia, Chris Emmanuel.

I’ve got this groove going, kind of like a pulse. The way I play the melody with the digital delay, it sounds like there’s at least two things going on at the same time. In fact, people are always looking around to see who else is playing! Or they’re at least looking around for a lot more equipment, and there isn’t any.

Is “Initiation” your standout concert piece?

Yeah, but I play a lot of different styles. I play flatpick style as well as thumb- and fingerstyle. I play blues, jazz and country, but I’m a melody player; that’s my main criteria. I try to make people feel good when I play; I’m in the happiness business!

“Initiation” isn’t the only song where you hit your guitar with your hands to evoke a percussion effect. Has your style ever been compared to Michael Hedges or Preston Reed?

I think it’s totally different. I don’t know whether people compare me to those guys or not, but occasionally people will say, “Do you listen to a lot of Michael Hedges?,” and the truth is, I didn’t. But I really liked what he did. In fact, when we were making Only, we played a lot of Michael Hedges’ albums in the control room before we started working. He had a beautiful tone.

How did you earn the coveted “Certified Guitar Player” (C.G.P.) designation?

That had to come from Chet, and it was a total surprise to me when he gave me the award, which says “For A Lifetime Contribution to the Art of Finger-Style Guitar.”

It’s his way of recognizing someone who has taken what he’s done and has done something different. But I’ve also taught all over the world, and I continue to do that; I’m like an ambassador for him for that style. I try to pass it on to others.

Only is all original material, but do you have any favorite covers, besides “Waltzing Matilda?”

I really enjoy Beatles songs, but I choose carefully what I want to play. Everything has to work; the arrangement has to work and the melody has to be strong.

Why was Only recorded in Germany?

A friend of mine has a great studio there. My wife and daughters and I had moved from Australia to England, and I didn’t want to go all the way back to Austraila to record. At the time, my youngest daughter was having some health problems, so I didn’t want to be far away. She’s fine now.

Did you write specifically for that album, especially since it was your first true solo album?

There were some songs I’d written a few years ago that I reworked, and I started writing the rest of them on the road. I didn’t write specifically for that project, but once I got my freedom from another label, I wanted to make a solo acoustic album because a lot of people told me they wanted to hear me play on my own.

One could infer that “Train to Dusseldorf” might have been written specifically for Only.

That was written about two weeks before we recorded, but my only criteria was to try and write the best songs I can.

How long did it take to record the album?

Two afternoons. Everything was one take, except for track number five, “Questions.” I did a take of it the first evening, came back and listened to it the next morning, and said “Nah, I can do it better; I can get a better feel on it,” so I did it again. But everything else, I just played once.

“Biskie” is about a minute and half long, and the last 10 seconds have about a zillion notes.

(Laughs) I wrote it, then I did have to practice it. It’s the name of the daughter of a friend of mine named Will Harmon who lives in Knoxville. She’s been to a lot of my shows; she’s really sweet. She became a fan, so I wrote her a song!

You played at the closing ceremonies for the 2000 Sydney Olympics. How did it feel to be performing for a television audience estimated at 2.75 billion?

Well, NBC went to a commercial break (chuckles)… But it was very exciting. My brother and I rehearsed for about a week; we did a John Jorgenson song called “Back on Terra Firma.” There were 150,000 people in the stadium; 30,000 people on the ground there. That was just the live gig not counting the television feed, so plenty of people heard it.

After a long career, you’ve finally gotten a true solo album out. Are you satisfied with the way Only turned out?

Well, at the time, I did the best I could in the short time I had, and I think the strength of the songwriting and performance is there. I can play the songs a lot better now – I’ve “polished” them – plus I’ve written a lot of new songs, so my next album will be solo acoustic, as well. Hopefully, the next album will be out around April.

The fact it only took Tommy Emmanuel two afternoons to record Only, plus the fact that all but one track on the album were first takes underlines the level of his abilities. There are still musicians who can be entertainers without videos and other visual aids, and Emmanuel exemplifies the same dedication as his mentor, Chet Atkins.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Dec ’02 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.