Rick Malkin

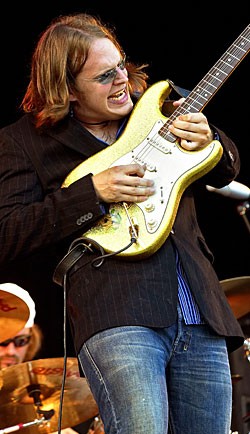

Guitarist/producer Jerry Kennedy, recipient of four Grammy awards, is proud of his three sons, all of whom are accomplished musicians and songwriters.

The Nashville veteran’s oldest, Gordon, is a Grammy-winning songwriter (Song of the Year for co-writing Eric Clapton’s “Change the World”) and a Grammy-winning guitarist (he was the other guitar player on Peter Frampton’s Fingerprints). Middle son Bryan has toured with and written hits for Garth Brooks.

A song written by youngest son Shelby (“I’m A Survivor”) is the theme for Reba McIntire’s television show, and he works as the Director of Writer/Publisher Relations in the Nashville offices of BMI.

However, Gordon is the family gearhound, and thus caretaker of the bulk of his father’s instruments, as well as an avid collector himself. Both reside in the Nashville area.

Jerry Kennedy is originally from Shreveport, Louisiana, and his first steps to playing an instrument followed familiar footsteps.

“My folks got me a Silvertone guitar when I was eight or nine,” he said. “I’d been beating on broomsticks and other things before then.” He took lessons from local legend Tillman Franks, and later got a small Martin acoustic. He attended “Louisiana Hayride” shows at the legendary Shreveport Municipal Auditorium, and recalls Hank Williams’ last performance there (“I was a kid sittin’ on the front row”). He also has a unique recollection about one of Elvis Presley’s performances at that venue.

“Me and a friend went to see the show,” he recounted. “But we got mad at all of the girls screamin’, because we couldn’t hear Scotty (Moore) when Elvis was doin’ his shakin’. It upset us that we couldn’t hear the guitar.”

When he was 11 years old, Kennedy signed with RCA, and recorded singles that included Chet Atkins on some sessions.

“I did two sides in Dallas and four sides in Nashville, and Chet was the leader on the Nashville sessions. I was just a kid, and it was very intimidating; he was my idol at the time and I’d listened to as much of his stuff as I could get my hands on.”

In the mid ’50s, Kennedy also got his first electric guitar, a Fender Telecaster. By the age of 18, he was in the “Hayride” house band. Later, he went on the road with Johnny Horton and acquired a ’58 Les Paul Standard.

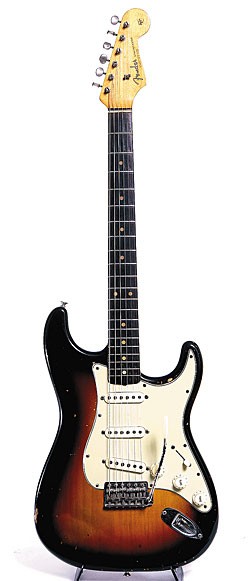

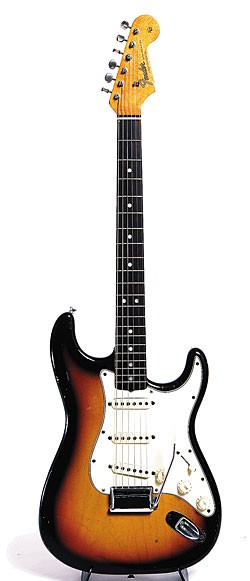

“When I was playing dances with Horton, that guitar was too heavy,” he remarked. “Billy Sanford, another picker from Shreveport, had a Stratocaster that was a lot lighter, so I swapped with him and moved to Nashville in March of 1961. Shelby Singleton talked me into coming here to record, and after I got here I realized I had the wrong kind of guitar for the kind of music he was doing. So I went to Hewgley’s Music and traded that Strat for a (Gibson ES-) 335.”

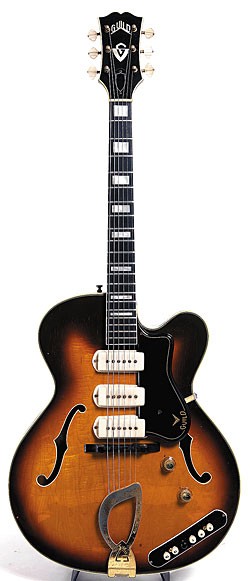

That ’61 335 is something of an icon – Kennedy played it while recording the guitar parts on Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman,” Elvis Presley’s “Good Luck Charm,” Tammy Wynette’s “Stand By Your Man,” and Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde album, and countless other songs and albums. Furthermore, Gordon Kennedy has used the guitar on sessions with Jewel, Garth Brooks, Frampton, SheDaisy, and others. It’s now on display at the Musician’s Hall of Fame in downtown Nashville.

Jerry detailed that the unusual-looking gizmo on the guitar is a palm pedal built by Dean Porter and installed circa 1963.

“He built one for me and one for Grady Martin,” he recalled. “That’s the only two I know of. It was something different; a crazy idea, but I said ‘Let’s go for it.’”

He also recalled using an Ampeg amplifier on “Pretty Woman,” which he described as “…one of the warmest-sounding amps I’ve ever used. After that, a Fender Twin owned by the studio became my favorite. If I’d been the wrong kind of guy, I would have eased out the back door with it! But I always looked forward to playing it, and since then I’ve pretty much stayed with Fenders.”

Kennedy acquired other requisite instruments for studio musicians of the era, including a Dobro (heard on “Harper Valley PTA,” “Engine #9,” and other hits), which he and legendary producer Harold Bradley bought in the mid ’60s, and a Danelectro six-string bass guitar he played on sessions by Ray Price and Brenda Lee and more notably on “Ahab the Arab” by Ray Stevens. “We loosened the pickup on it to where it was kinda touchin’ the strings to get that sound,” he noted. Bradley is also cited by Kennedy as the creator of the fabled Nashville “tick-tack” sound, achieved by doubling a Danelectro six-string bass guitar with an upright bass.

He later acquired a ’62 Sobrinos De Domingo Esteo flamenco guitar that Roy Orbison brought back from Spain, and there’s a Gibson ES-175 given to him by Howard Roberts.

In 1966, Jerry became the Vice-President of Mercury Records’ Nashville division, succeeding Singleton. The shift to the producer’s chair had begun in ’62, when Singleton asked Jerry to produce a Rex Allen session. He gradually got more into production rather than session work, and a list of recording artists with whom he’s worked is too long to be printed here; the perception would be that a list of artists with whom he hasn’t worked would be shorter. His extensive work with Jerry Lee Lewis and the Statler Brothers is noteworthy, and he even produced the Statlers’ hilarious comedy material in the ’70s, when they lampooned small-town country bands under the pseudonym Lester “Roadhog” Moran & His Cadillac Cowboys.

“That was Lew Dewitt on guitar,” Kennedy recalled with a laugh. “I don’t remember what he played, but it sounds awful. And it was awesome that they could sing off-key. It took a lot of talent to sing like that, and for Lew to play like that, although we’ve all tried to live that project down all these years. Somebody told me that album was on every bus leaving Nashville back when it was released – a must for the bus. It’s good to know that people still remember Roadhog. We’re proud of it, but we wouldn’t want to do it again.”

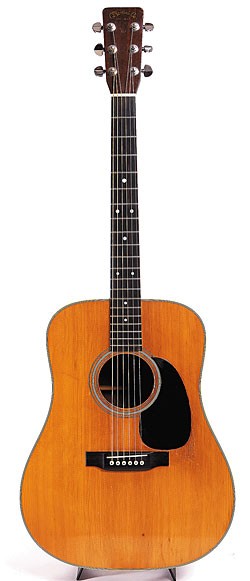

The career move to producer didn’t stop Kennedy from garnering new instruments that provided new sounds, including a ’67 Coral Electric Sitar, and he got a Martin acoustic in the early ’70s from Hank Williams, Jr., with Bradley as go-between. He also toured on occasion with selected artists throughout the ensuing decades.

Jerry now considers himself retired, and takes a lot of pride in the accomplishments of his sons.

“All three are great songwriters,” he summarized. They’ve all written songs that meant something. I’m prouder of those three boys than anything I ever did.”

As the first-born child of a Nashville veteran, Gordon Kennedy recalls seeing guitars and amplifiers around his childhood home “since I can remember. We had a piano and a juke box when we lived in Goodletsville, and the juke box was stuffed with 45s that my father was involved with, as either a player or producer. The earliest things I can remember that he produced was some of Roger Miller’s stuff.

“When I tried to break into the studio scene here, there were a couple of people, like Harold Bradley and Chip Young, who showed me the ropes; Jerry Reed, too. Besides my father, guys like that were the ones who pulled me aside and said things like, ‘Let me show you how to do this.’ And Chip would show me how to make my strings last longer – little tricks of the trade. They were willing to pass things along to me instead of looking at me like I was a new kid. Every time I met Chet Atkins, he always had something kind and sweet to say about my dad.”

While Gordon had access to his father’s instruments at an early age, he recalls owning the ubiquitous Harmony acoustic guitar. “But when I started to get serious about guitar, my dad could see what was coming,” he said. “So he got me a Fender Telecaster for Christmas when I was 15, and I still use it. Along with his 335, I’ve probably used those two guitars on 80 percent of the recordings I’ve played on.”

Two months after he got the Tele, he got his first gig, playing in a band with Jerry Reed’s daughter at a school talent show. The set list consisted of the Pointer Sisters’ “Yes We Can Can,” Hank Williams’ “Hey Good Lookin’,” and the Doobie Brothers’ “Listen to the Music.” And Jerry Reed helped Gordon adjust his amp for the gig – by turning it up!

“I never really wanted to play in Top 40 bands,” Gordon said. “But Dann Huff, who’s now a top producer in Nashville and L.A., his brother David, and I had a band in high school, and we played everything from McCartney to Bachman-Turner Overdrive to Brothers Johnson to Barry Manilow; we were all over the map. And even back then we picked things to play because they were great songs, not because of a certain guitar part.”

The younger Kennedy came to public notice in a contemporary Christian band called Whiteheart.

“The third band I ever played in had David Huff on drums again, and Larry Stewart and David Ennis, who would join Restless Heart,” he said. “And after that band, I moved over to Whiteheart. I joined to fill in for Dann (Huff) for three shows, and was with them for six years. I think there were some Dove-award nominations along the way, but we lost to Petra every year!”

“Change the World” was co-written by Kennedy, Wayne Kirkpatrick and Tommy Sims. Performed by Clapton for the movie Phenomenon, the song had phenomenal chart success in its own right a decade ago.

“It holds the record for being in the Top 20 for 81 straight weeks, starting in the summer of ’96,” Kennedy enthused. “And I think it was in the top spot for 17 weeks. The other day, I decided to buy some different versions of that song, and I think I downloaded – legally, mind you – 23 versions of it.”

As for his use of guitars for songwriting, Gordon noted “Three-fourths of the time, for me it involves an acoustic guitar to start a song. Sometimes I’ll fool myself into thinking I’m practicing on electric, and I’ll just be riffing, but I’ll hear something, then I’ll record it so it may end up in a song.

“I have some gourmet guitars I like to play just because they feel so good – Lowden, Avalon, Langejans – and there are certain acoustics I like better live because of their pickup system. Lately, I’ve been playing the Frampton model Martin, and I have a Clapton Martin I got when all of the action on the song was going on. I also like writing on my ’59 Gibson J-45.”

As for his guitar-collecting propensity, Gordon noted, “To me, ‘collecting’ is sort of a loose term because I use those instruments. It just so happens that some of the things I enjoy using the most are among the most soughtafter instruments around.”

Gordon began his education about the importance of classic instruments while he was still in high school.

“There was a guitar in a closet at home; it looked like my Telecaster and didn’t have a case,” he recalled. “I checked it out; it was an Esquire. I started playing it, and that’s what made me notice the difference between something made in the ’70s and something made in the ’50s. Then I’d compare guitars at local music stores to my dad’s ’61 ES-335. But not every ’59 Strat you pick up is gonna be a great guitar; you still have to compare.”

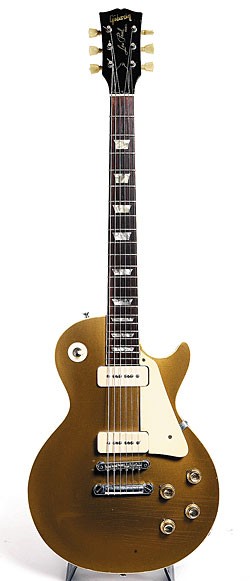

Kennedy’s comparison shopping credo is exemplified by the story of his purchase of a ’59 Gibson Les Paul Standard that was formerly owned by John Sebastian of the Lovin’ Spoonful. He examined a total of five late-’50s Bursts at one retailer.

“The Sebastian Les Paul sounded the best, out of the case,” he recounted. “The other four – two ’58s and two ’59s – were in new condition, and had these stories about people playing them for 30 minutes then storing them. But the Sebastian guitar sounded great plugged in, and when I heard it through a little blackface (Fender) Deluxe Reverb, it was over. The other four weren’t even close. So they’re not always the same just because of a serial number or because they’ve got P.A.F. pickups.”

In 1999, a cousin in Shreveport served as the inspiration for his acquisition of a ’54 Les Paul similar to the one the cousin owned decades before. Kennedy bought the Les Paul, nine other guitars, and 11 amplifiers from a seller in Norfolk, Nebraska, and he and a friend drove a cargo van to pick up the cache.

“It took 15 hours to drive there, and 16 hours comin’ back,” he chuckled. “The three best guitars in the bunch were the goldtop, a ’61 Telecaster, and a ’59 Strat with ‘November’ stenciled in it; I was born in November of 1959. There were some great amps in there, as well. I felt this (transaction) was meant to be; I stayed in touch with (the sellers) afterwards and let them know what records I was using certain guitars on.”

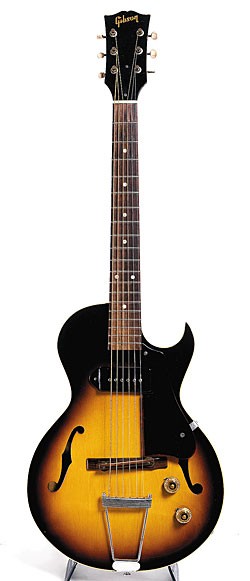

Gordon has used the goldtop on “Austin City Limits” backing Garth Brooks, and on session work with Faith Hill and SheDaisy, among others. He also owns a ’62 SG/Les Paul Standard with a sideways vibrato that he uses on occasion, but admits, “It’s hard to gravitate toward that one with Sebastian’s Les Paul sitting nearby. Also, an SG is a little awkward for me; it just has a different feel.”

The aforementioned “closet Esquire” is a ’57 that Jerry Kennedy bought from Harold Bradley for $35 in the ’60s, and Gordon used it on “Float” on Frampton’s Fingerprints album. His 1960 Gretsch 6120 was a gift from Garth Brooks, and he has used it on television shows with Brooks.

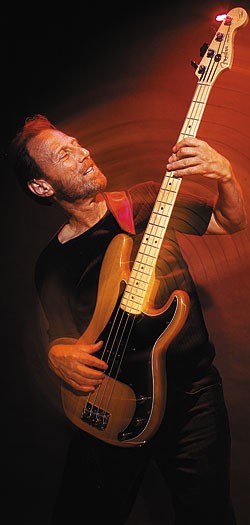

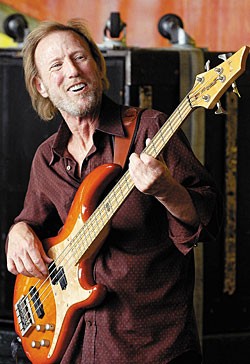

The younger Kennedy acquired a ’59 Fender Precision Bass from Jerry Reed. “He called one day and asked me to sell it,” Gordon recalled. “I asked him to get me the (serial) number off of the neck plate. I called him back 20 minutes later and said ‘Jerry, I ain’t sellin’ this bass for you. I’m buyin’ it!’ I wanted it because it was his bass, and again, I was born in ’59. He fought me for a while, with a sense of humor. About a month later, after he and I had been doing some producing together, he said, ‘I need to settle up with you, so would you be willin’ to take that bass?’ So he gave it to me. I’ve got two other basses – a newer Höfner that Leland Sklar hand-picked for me, and an early-’90s Rickenbacker.”

Gordon also has an assemblage of classic amplifiers. “These days, the ’59 tweed (Fender) Twin is rockin’ my world. To me, it’s what everything else wants to be when it grows up! It’s spectacular.”

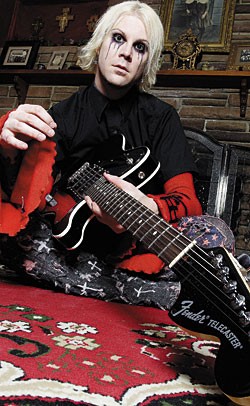

His appreciation for historically-important instruments besides his father’s ES-335 began several years ago, while on tour with a triple bill of Frampton, Styx, and Nelson, where he played, onstage, the Telecaster Joe Walsh used on the James Gang’s “Funk #49.”

These days, Gordon is more focused on songwriting than concerts and touring, and has a new home studio to handle.

“My publishing company is beatin’ my door down, yellin’ ‘Where’s our songs?’,” he chuckled. “I’ve got a quota to hand in, and my studio’s up and running. Of the first four songs I did, one already has a hold placed on it.

“But Peter and I will be working together every chance we get,” he summarized. “I also wrote with Lynyrd Skynyrd a week ago, so I’m staying busy.”

Special thanks to Peter Frampton and Lisa Jenkins.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s October 2007 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.