Americans tend to link the beginnings of the Beatles phenomenon to a specific date – February 9, 1964, when the group first appeared on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” The truth, as always, is that the band’s records had crashed the American charts weeks before, and the run-up to this seemingly overnight phenomenon had taken years.

The Beatles runaway success in the U.K. began in early 1963, which means it has been 50 years since their breakthrough from regional popularity to dominance of the U.K. music scene. Despite all that has come since, no musical act has been more influential. They changed the way pop music was made, sold, even thought of, and brought the guitar even more to the forefront. It’s amazing how many players continue to cite the band as an influence, and new generations discovering their records are captured by the ingenuity, scope, and talent of the (in John Lennon’s words) “Band that made it very big.”

Recently, this was highlighted by a period publication titled Big Beat Boys, issued by Britain’s top music weekly Melody Maker in the spring of 1963. There are thousands of souvenir booklets from the heyday of Beatlemania, but this early one is a bit different. The focus of this “look at the thriving international beat scene – in which Britain is playing a bigger part than ever before” was on the Beatles and other “beat” bands in their wake – alongside a few already established acts still rated as “Beat” performers. Melody Maker was aimed at music biz professionals and serious fans, especially musicians. All advertising in Big Beat Boys is for guitars and amps – the tools of the revolution, aimed not at a female fan base, but budding players. “Just get an electric guitar” every page hints, and this could be you! Not just the Beatles, but every act featured has a guitar-centric lineup, and it shows how inextricably linked this musical explosion was to the electric guitar. Of course, between the street-level skiffle of the late ’50s and the rise (from 1960) of the instrumental quartet The Shadows, it’s safe to say the youth of the U.K. were already in guitar-oriented mode. The Shadows had established electric guitar as a viable, even career-making solo instrument, and similar bands had sprung up all over England. Despite Decca producer Dick Rowe’s rejecting the Beatles in early ’62 with a pithy “Groups with guitars are on the way out, Mr. Epstein!” the truth was the groundswell of singing, jiving guitarists had not yet even been seriously tapped!

Even at this early point, the Beatles combined guitars, drums, and vocal in a compelling way. Compared to the polite vocals of most English artistes, Lennon and McCartney’s full-throated singing and bracing harmonies were a revelation. The combination of uninhibited strumming and “big beat” drumming was less unusual on their Liverpool home turf, but to the rest of the country an excitingly novel sound. The more studied and controlled echo-soaked instrumental approach of the Shadows was the 1962 template for most English bands. The beloved “Shads” were still rated as major stars in Big Beat Boys, with a full feature. Others cut from the same cloth were also profiled. Top among them were Jet Harris and Tony Meehan, the Shadows’ rhythm section, who had quit the group but re-teamed as an instrumental duo. Their twanging, Duane-Eddyesque early-’63 smash “Diamonds” was led by Jet’s six-string bass; when he tried to sing, the jig was up! Another was The Tornadoes, producer Joe Meek’s chart-topping quintet that achieved a lone success in the U.S. with the inimitable single, “Telstar.” The record’s combination of unearthly electronic keyboard and shimmering, echoed guitar was certainly unique, but lost appeal quickly when the Beatles ushered in the new “singing, swinging” Beat style. In early ’63, these older bands were still rated as stars.

While hardly achieved overnight, the Beatles’ U.K. success proved unprecedented in scope. By the spring of ’63, the band’s audience had been building for more than two years; domination of the massive Liverpool scene was secured in January, 1962, when the band won the first Merseybeat popularity poll. Their initial Parlophone 45, “Love Me Do,” released in November of ’62, was huge in the north (possibly juiced by manager Brian Epstein “buying in” thousands) but only a middling national hit. And while this catchy (if fairly crude) sing-along gave little indication of the songwriting talent of its authors, it was the fact that those writers were also the band’s vocalists that was noteworthy. While some American rock and roll artists composed their own material, in Britain it was almost unknown. At the time, the use of harmonica was trendy due to hits like Bruce Chanel’s “Hey Baby” and Frank Ifield’s U.K. smash “I Remember You.” Viewed as a bit of an oddball record by the U.K. press, “Love Me Do” was a solid start but it was the Beatles next single that would really launch them – and the Beat era – into the stratosphere.

“Please Please Me” with its combination of vibrant harmony, pumping bass, harmonica, and guitar and drum hooks (and surprisingly urgent lyrical leer) was not like anything heard before. Released on Friday, January 11 1963 this record quickly stormed the U.K. charts, ending up at either #1 or #2 depending on which chart one consulted. Within a month, the Beatles were called to EMI’s Abbey Road studios to record a full LP. This first album was intended as a quick cash-in, but the Beatles insisted, despite the limited time and budget, that every track be given the same care as their singles. “We’d been through buying LP’s filled with rubbish,” Lennon recalled years later, explaining the groups’ insistence that the collection stand on its own merits. Luckily, EMI producer George Martin concurred, and the public responded – the band’s first LP would spend 30 weeks at #1 on the Record Retailer chart – only losing that spot to the group’s second LP late in the year! The group’s April 1963 single “From Me To You” shot straight to #1, consolidating their status – and the reputation of the Lennon-McCartney songwriting team.

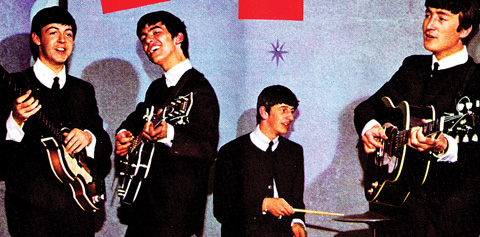

At the time Big Beat Boys was published, this was the sum total of the Beatles’ output (unless you count the earlier “My Bonnie”) but they were already described as “The most exciting sound ever to hit British records… Their crackling in-person performances knock out audiences all over Britain.” The band was then trucking up and down the country through one of the harshest winters in memory, touring with (and gaining headline status over) established stars including teen sensation Helen Shapiro, Americans Chris Montez and Tommy Roe, and even the great Roy Orbison. “Booming Beatles Beat All – They have the whole pop world in their hands,” mused Big Beat Boys author Chris Roberts. Of special interest to guitarists, this fabulous run-on sentence specifically credits the “Boys’” instruments: “John, who plays an American Rickenbacker guitar, used his harmonica as an experiment on a few dates of record, with George’s whining Gretsch guitar sound close behind, and Paul’s Höfner bass bouncing along beneath.” Interestingly, the pictures show Lennon’s Gibson J-160E, which was not mentioned. “And John, Paul, and George find time to sing – in snappy coloured voices – at the same time,” the text goes on, in charming phrasing. There’s only a passing mention of those “famous” haircuts!

Other talent from their hometown was also featured. In March, 1963, “Please Please Me” was followed up the charts by Liverpool rivals Gerry and the Pacemakers, also under the wing of Brian Epstein and beneficiaries of a unique Beatles castoff. When George Martin signed the Beatles, he had a song that he thought perfect to launch them into the charts – “How Do You Do It,” an upbeat pop number by Londoner Mitch Murray. A defining moment in Beatles history came with the group – Lennon in particular – rejecting the idea. The band worked up an arrangement and recorded it in a brisk if half-hearted manor, but made it clear they preferred their own material. This refusal to be molded by an all-powerful producer was unprecedented in British pop. To his eternal credit, Martin acquiesced, but simply handed the arrangement to Gerry Marsden and his group, who scored an almost instant #1 hit in March of ’63, followed by a second with “I Like It.” Big Beat Boys’ Gerry proudly cradles his new Gretsch Tennessean on the back color cover.

Several other northern acts were profiled – Liverpool musicians’ favorites The Big 3 merited a two-page spread showing them with a classic U.K. “pre-fame” instrumental lineup of a hollowbody Framus Star Bass and Japanese-made Guyatone solidbody. Epstein protege Billy J. Kramer & The Dakotas got a feature. From nearby Manchester came Freddie and the Dreamers, alongside a very young Hollies, still clad in leather like the Hamburg-era Beatles. All of these acts had released but one 45 at this point. London instrumental bands Peter Jay and the Jaywalkers and Sounds Incorporated merited mentions, as well – both brandished saxophones alongside guitars, but had limited chart success despite being crack performing outfits. Vocal/instrumental groups Shane Fenton and the Fentones, and Brian Poole and the Tremeloes, were in the older star-plus-backing group mode – the latter being the band Decca signed instead of the Beatles in 1962!

The ’63 “Big Beat” umbrella covered more than Beatlesque bands. Joe Brown and His Bruvvers were an older-sounding act mixing rock and roll with English music-hall echoes. The Springfields were a pop-folk trio who hit with “Silver Threads And Golden Needles.” The group was short-lived, but gave the world the glorious voice of Dusty Springfield, who went solo soon after. An even more unusual crew was The Karl Denver Trio, fronted by an aging Scottish yodeler! They are shown with a Framus Star Bass, Guild X-350, and Karl’s Martin D-28E. Several veteran American performers rated write-ups, including Jerry Lee Lewis (re-starting his U.K. career), Duane Eddy, the Everly Brothers and the late Buddy Holly, with an update on the Sonny-Curtis-led Crickets. Still, the focus was clearly on emerging home-grown performers.

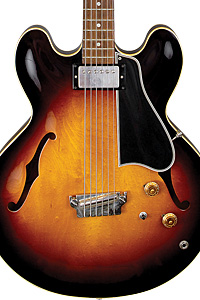

Of interest to guitar fans, Big Beat Boys carries ads from most major British instrument importer/distributors. The inside cover was taken by Selmer, the 800-pound gorilla of U.K. guitar sales. Guitar specialists since the ’30s, Selmer represented both Fender and Gibson in England, plus long-time staple Höfner, from Germany, and the budget Futurama house brand, applied to various foreign-made pieces. The company had just begun importing the unusual Höfner 500/1 violin bass due to demand from players who had seen it in Paul McCartney’s hands. All these Selmer-distributed brands would be associated with the Beatles at some point, from George’s early Futurama solidbody through the silverface amps used in Let It Be. Arbiter had the inside back cover, featuring Gretsch guitars and the notoriously oddball Trixon drums. Rose-Morris did not yet have the Rickenbacker line – at this point John Lennon’s signature guitar brand was not officially available in the U.K.. The product proffered in Big Beat Boys was Ampeg amplifiers, which had little impact in the land of Vox. Rosetti offered the Epiphone line featuring the semi-hollow Rivoli bass, already a hot item in the U.K..

The U.K.’s top musical manufacturers, JMI/Vox and Burns, had full-page ads, as well. Burns was relatively straightforward with typical pseudoscientific prose, introducing their ill-fated transistor amps and picturing the rare SplitSound six-string bass. JMI showed the Shadows (in full color) but oddly enough without guitars or amps, apparently so confident in their Vox gear they could relax “away from the bustle of show business and its attendant worries…”! Smaller fries Watkins/WEM and Fenton-Weill also had format ads – WEM’s an attractive (likely expensive) full-color spread. Both offered mid-priced gear popular with up-and-coming acts but rarely seen in professional groups. Watkins features the well-regarded Copicat echo and “New Circuit 4 Guitar” which had not yet been named the Rapier 44. There are interesting ads from the three top retailer’s in England’s north, where the “Beat boom” was still centered. Frank Hessey’s and Rushworth’s of Liverpool, along with Barratt’s of Manchester, touted their famous beat group customers and listed their extensive guitar offerings. Rushworth’s and Hessey’s counted the Beatles as customers – the Bigsby for Lennon’s Rickenbacker was fitted at Hessey’s, while their J-160E’s were ordered through Rushworth’s.

With its breathless but musician-friendly tone, Big Beat Boys is a fascinating snapshot of the Beatles and early Beat scene when it was an emerging phenomenon, confined to the U.K. and viewed as a novelty. It must have seemed like a guitar-twanging flash in the pan at the time; it’s likely nobody had any inkling of what the Beatles would become or how great their influence would be – pop groups were expected to have a lifespan of months or perhaps a few years in the limelight. Still, it made showbiz seem like good fun, if nothing else! Few besides hardcore fans remember Carl Denver, Shane Fenton or even the once-mighty Big 3 today, but they were all part of this initial U.K. beat explosion. Guitars, electric basses, and drums (with the occasional harmonica or keyboard) were suddenly the most important thing in the world to any self-respecting teenaged boy (and even a few girls). While most of these acts are largely forgotten, thanks to the talent, determination and sheer brilliance of the Beatles, we’re still feeling those Big Beat reverberations 50 years on.

This article originally appeared in VG May 2013 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.