Manuel Ramírez was one of the most important makers of the Madrid school at the turn of the 20th century. His well-organized shop was staffed by talented makers such as Santos Hernandez, Domingo Esteso, Antonio Emilio Pascual Viudes, and Modesto Borreguero (Enrique Garcia having previously left for Barcelona, and Julian Gómez Ramírez having left for Paris).

Many collectors are familiar with his most famous instrument, the wonderful example from 1912 played for so many years by Andrés Segovia, and now residing in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. This instrument was actually built by Santos Hernandez, who later restored the instrument in 1922, inserting his own restoration label below the Ramirez label. This instrument, which was originally made as an 11-string guitar for Antonio Gimenez Manjon, was one of Manuel’s finest models, the kind of ne plus ultra guitar most collectors today tend to favor, often to the detriment of the more common examples.

However, these expensive deluxe models were hardly the bread and butter guitars of the Ramírez shop, as customers who could afford the expensive models were few and far between. In fact, according to a Manuel Ramírez catalog issued circa 1912, he offered no less than 48 models ranging in price from 10 to 1,000 Pesetas. By contrast, the violins Manuel made personally ranged in price from 200 to 1,000 Pesetas for the finest violin cello. To put those prices in perspective, 1,000 Pesetas represented the average annual salary of a skilled tradesman. So it shouldn’t surprise us that most of the instruments he sold were modestly priced examples.

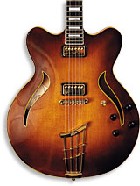

Our featured instrument this month is a Model 26 guitar made for export to the firm of Romero Agromayor and Company in South America, one of the leading importers of fine Spanish guitars in Buenos Aires, Argentina. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Uruguayan cities of Buenos Aires and Montevideo were home to millions of Spanish expatriates who had fled the civil war of 1868-1875. Many started over in South America, often earning small fortunes with the golden opportunities offered by the New World. Longing for a piece of the homeland, though, they would order fine guitars from Spanish makers, and Romero Agromayor made a small fortune importing these instruments to fill demand. In fact, so important was this trade that most makers of the era including Manuel Ramírez had special labels printed, as we see in this instrument.

Curiously, according to the catalog description, this guitar is one of “Special construction for playing popular airs (flamenco).” This is one of the earliest written references I’ve seen to date in which guitars are indicated to be specifically for “flamenco” as opposed to general usage or the concert stage. Later in the catalog, Manuel mentions guitars for “orchestra” of large model, and finally, the guitars for the concert stage, which in today’s lexicon would presumably mean “classical” guitars, although they are never referred to as such. Though possibly intended as a flamenco guitar in Spain, in South America there would have been little demand or awareness of flamenco, as few flamencos (a.k.a. gypsies) had ventured outside of Spain in those days to visit South America. It’s interesting to note that this guitar never had any golpeadores (tapping plates) installed, an essential feature of any working flamenco guitar.

The catalog description of this Model 26 is quite interesting, as it is a cypress guitar with a “top of spruce (pino abete) with a soundhole inlaid with fine black and white lines, full fan strutting, neck of cedar, fingerboard of rosewood with medium-sized frets, top and back domed and inlaid with bandings, a bridge of rosewood with rosettes of mother of pearl and veneer of ivory, wooden pegs of rosewood.”

Indeed, this exactly describes our instrument here, including the sizes stated. The catalog indicates it sold new for 50 Pesetas, and the tuning machines (which the catalog lists as an upgrade), cost an additional 5 Pesetas. Rarely did they export guitars with wooden friction pegs to the Rio de la Plata area, as the generally high humidity there made their usage very difficult. The machines appear to be American made, of the type used by Lyon & Healy during the same period. Manuel may have been ordering these tuning machines from Chicago. His better models were equipped with deluxe German-made tuning machines. The “domed” top and back is in keeping with the popular flamenco tastes of that time that favored this so-called “tablao” guitar for flamenco usage. These were very domed (arched) instruments that originally evolved in Sevilla with Manuel Soto y Solares, and migrated north to Madrid with flamenco players. In Madrid, Francisco Gonzalez and José Ramírez (older brother of Manuel) were the most prominent advocates of this style of construction, which died out by 1920, replaced with the full-blown, flatter Torres model favored by Manuel in his more expensive concert models.

Through comparative studies, I have determined this instrument was most likely made by Modesto Borreguero, as the heel is very characteristic of his work, along with several other distinctive features, such as the shape of the internal foot, the brace profiles, and the purfling and head work. Borreguero often made his neck and head of one sawn piece, rather than grafting the head to the neck, as was the more traditional Spanish custom. This instrument has an ungrafted head. It is my observation that Santos (and Antonio Emilio Pascual Viudes before him) made the most deluxe models, Esteso made the next level, and Borreguero covered the more mundane models, as was fitting to their abilities. Manuel rarely made guitars personally, although at least one example is known, dedicated to P. Gonzalez Campos on the label. Manuel, for the most part, directed the shop and when orders warranted, made some very fine violins.

Modesto Borreguero stayed on at the Ramírez shop after Manuel died in 1916 (after which the guitars were labeled, “Viuda de Manuel Ramírez”). During the Spanish Civil war (1936-’39) he lost his shop and his wife, and floundered until he was able to share shop space with Hernandez and Aguado, who learned to make guitars from Borreguero before going on to surpass Borreguero in fame and esteem. Later, he also taught Vicente Pérez Camacho to make guitars while working for the Casa Garrido. His last guitars date to around 1963, making him one of the last surviving members of the original Manuel Ramírez workshop to work in Madrid, the other being Antonio Emilio Pascual Viudes, who had emigrated to Buenos Aires in 1909 and died there circa ’61.

At first glance, this appears to be a rather indifferent instrument, with the top looking for all the world like it had been salvaged from an orange crate, the fingerboard (with original frets still intact) showing the tear out from the hand plane Borreguero never bothered to scrape clean, and the purfling work, which meanders seriously around the border, not to mention enough glue runs inside to make a second guitar. But place this in the hands of a skilled player, and watch their eyes pop out. Surely if ever there was a poster child for the adage that the wood alone does not make a fine instrument, it is this guitar. Clearly, the design is what’s important, not the quality of the wood. In this department, Borreguero got all the important talking points nailed down, from neck angle to bracing to bridge design and beyond. Despite its nearly century of age and several heavy-handed repairs, this instrument still trembles in your hand and explodes with sound. It certainly puts to rest the ridiculous notion that guitars have a limited life span, and will “go dead” if played too much or too aggressively. As you can see from the playing wear, this guitar has clearly experienced both to extremes and yet despite the zilch-grade wood, it is still at the top of its game. Just goes to show, you can’t judge a book by its cover.

Photo: R.E. Bruné

This article originally appeared in VG‘s July ’06 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.