For those of you checking out our Echoplex series for the first time (and regular readers, too), a brief glance back: Part I perused the groundbreaking use of echo by Les Paul, plus the first dedicated echo machine – Ray Butts’ EchoSonic amplifier. In a nutshell, the EchoSonic was the only commercially available echo-producing device in the U.S. prior to 1960. All other echo came from converted three-head reel-to-reel tape decks, a standard in recording studios by the end of the decade. Since only about 68 of the custom-ordered EchoSonics were sold and only a handful of players experimented using tape decks, the majority of live musical performances of the ’50s lacked echo on guitar and vocals.

Part II covered the first commercially available, American-made outboard echo – the early-’60s Ecco-Fonic – and included an interview with its original endorsee, Del Casher, and his late-’59 prototype. A number of less-advanced, early-’60s models from Europe were glanced at and one in particular, the Meazzi, may have been available as early as the late ’50s. An interview with Dick Denney of Vox in the book Stompbox (by Art Thompson, published by Miller Freeman, p. 158), discusses these units “…coming into England in 1958.” Even if this date is accurate, the Meazzi had little if any effect on American popular music and Thompson’s line (p. 20), “In the ’50s, tape-based echo units ruled the six-string scene” relates only to the studio. Fact is, most guitar players in the ’50s didn’t have echo or reverb. Put another way, there were probably less than 100 American players using echo in the ’50s and since Tennessee, California, and Ohio all had more than their share, that works out to less than two players in each of the remaining 47 states.

Last month, Part III introduced Don Dixon and Mike Battle, of Echoplex fame, along with a number of their prototypes from the late ’50s and early ’60s. Which brings us to this month’s topic, the early-to-mid-’60s production-model Echoplex and all that followed; those ubiquitous outboard echo units that immediately became the world standard for live applications. And not just for guitarists; many a singer used the Echoplex to fill out their sound long before the introduction of nonmagnetic (tapeless) analog and digital delays in the mid-to-late ’70s. Considering the continued demand for vintage models and replacement tapes, it seems safe to say a large number of guitarists still rely on this user-friendly tape echo. Here’s a look at the Don Dixon/Mike Battle/John Battle-designed, Market Electronics-made, C.M.I./Norlin-distributed models, plus a few others (don’t miss this month’s interviews, plus the sidebar “Maintaining Your Echoplex”).

Tube Models

EP-1 (early-to-mid ’60s): While the original models did not have any designation other than the brand name, later upgrades would necessitate the EP-1 name be applied posthumously. This model is easily distinguished from later versions by the smaller box and separate controls for echo volume and instrument volume. Along with the Echo Repeats control and the movable head to vary delay time, these three-knob Echoplexes were similar in function to the early-’60s Ecco-Fonics they displaced. One major difference was the use of a sliding record head to vary delay time, an improvement over the rotating playback head of the Ecco-Fonic.

Like the Ecco-Fonic, the Echoplex included a playback switch to disable the erase and record heads, allowing the signal that had been recorded previously to be played back over and over. This was long before cassette recorders were available and many musicians used this function as they would have a reel-to-reel deck – to play along with themselves, working out harmonies, listening critically, etc. To accommodate using this recorded track live, a footswitch was employed (instead of a slider switch, as on the Ecco-Fonic), allowing the unit to return to its echo function. A later prototype would attempt to make this early “sampler” more practical.

Another major improvement of the Echoplex was the patent-applied-for “endless loop magazine” tape cartridge, with twin reels and approximately two minutes of tape. This arrangement provided longer tape life and smoother operation. The Ecco-Fonic’s tape used a single reel and was only about 15 seconds in length. Reading the patent that was granted on the Echoplex, it’s apparent much of the unit’s originality was centered around this cartridge. Differences from the patent drawing and the production models are few, but include a 1/4″ output jack, a single 1/4″ input jack, a misplaced AC power cable, a different pinch roller release and the apparent lack of both a fuse and the record level adjustment.

As mentioned last month, the first of the production EP-1s were issued in brown leatherette boxes of the same dimensions as the later grey leatherette version. Nashville producer/session guitarist Vic Clay, who lived and played in Akron during the majority of the Echoplex’s production run (including his stint with Rex Humbard’s television show, seen in over 300 markets), received one of the first production models ca. 1963 in exchange for his metal-boxed prototype. The whereabouts of both units is unknown, as Clay traded in the brown box EP-1 (Serial No. 3?) for a grey EP-2 later on in the ’60s. Clay is unsure of certain differences between his brown EP-1 and his EP-2, but he remembers the modern tape cartridge was established by the EP-1’s release. He had to wind tape into the fixed cartridge on his prototype.

Once the surplus brown boxes were used, Market Electronics switched to the new grey color, otherwise the units were basically unchanged. The grey varied over the years and some have aged to an almost green tint.

A lever covering the input jack pivoted out of the way, disengaging the pinch roller release. The second input jack can be used instead of the first if no echo is desired, but once something is plugged into the first, both have echo. Unlike later models, the EP-1’s removable metal cover for the tape cartridge and heads included a bracket for wrapping the AC and attached output cables. This necessitated a taller lid than the later models. The on/off switch was built into the instrument volume pot and, like the EchoSonic and Ecco-Fonic, the Echoplex used a footswitch to activate/deactivate the echo.

EP-2 (mid-to-late ’60s): Following an important circuit change, the Echoplex received a new model designation and a larger cabinet. The wider box is one way to distinguish the EP-2 from the 1, with a hollow space added to the right side of the workings (note: the picture of page 20 of Stompbox has the negative reversed and a backward caption). This space allowed the AC and output cables to be stored more conveniently, particularly if the metal cover was left off to facilitate head cleaning (see step 15 of “Maintaining Your Echoplex” for important info on the AC cable).

Most important was combining the separate echo and instrument volume controls to a single pan pot, making the unit much more musician-friendly, especially for one-handed manipulation while performing. There was no more fussing over the blend between echo and instrument levels, as the single volume knob (with full instrument counterclockwise and full echo clockwise) was simply turned until the desired mix was achieved, all at a constant volume. Although it offered a bit less control in the fine-tuning department, this could be compensated for with the volume control on the amplifier. Setting the record level was more important than on the early model, but once set for the instrument or microphone, the EP-2 was a more practical live unit. A pilot light in place of the third knob was another practical addition, leaving room around the controls. The on/off switch was moved to the Repeat knob at this time.

EP-2 Sound-On-Sound (ca. 1970): Near the end of the tube Echoplex’s run, a final addition was made; the inclusion of a sound-on-sound switch in place of the second input jack. This defeated the erase head, as in the playback mode, but left the record head on and activated a separate playback head. A multitrack recorder of sorts was created, allowing the player to record a track and then add to it when that section of the tape came around again. If the second pass was successful, a third track could be added to the point where 1.) degradation of the earlier tracks became apparent, 2.) a mistake was made, or 3.) playback was desired. Back then, this feature was much more desirable.

A prototype was made having a footswitchable memory point that would return the tape to where a passage started and play it back at the touch of another footswitch. If the unit worked properly, you could start the machine at the beginning of a passage and stop it after a certain number of measures, with the tape returning to its memory point. Then the player could kick it in during a reprise and play a harmony part to it. The idea came from Dixon wanting to reproduce, in a performance situation, some of the tricks you could do at home with an Echoplex Sound-On-Sound. Absolute precision was required and the unit never went into production.

The first EP-2s with S.O.S. still came with the grey cabinet and white knobs, but a short run at the end of this model used black vinyl and knobs, as on all the solidstate models that followed. While the change from C.M.I. to Norlin around this time was devastating to the quality of most Gibson-made products, the independently owned Market Electronics was not greatly effected and its discontinued use of tubes was by choice, not the direct orders of new owners.

Solidstate Models

EP-3 (’70s): While the Ecco-Fonic’s downfall may have been switching to solidstate before the technology was thoroughly established (ca. ’63), the Echoplex did not discontinue use of the vacuum tube until the start of the ’70s. Their new transistorized unit was again designed by Mike Battle, who was by then working for Market Electronics full-time. And as always, it had to meet Don Dixon’s approval, which reportedly did not come right away.

The functions were left the same, with the addition of a 1/4″ jack for the output, replacing the attached cable and requiring/allowing the player to use a separate cord of any desired length and quality. A minor but important change for those who varied the delay time was turning around the tape transport, bringing the lever to the front of the deck and the numbers to the control panel where they could be seen more precisely. Long delay was now attained by sliding the erase/record head all the way to the right, as opposed to far left on the tube models. Unfortunately, the repeats (now called sustain) and echo volume (balance) knobs were moved closer together. For many players this was of no consequence, but others had to pay more attention when doing knob-turning special effects. The storage nook for the AC cord and spare cables moved from the right side to the left and the tape path’s cover was now molded plastic instead of metal. Later models have the symmetrical (propeller) knobs seen on the EP-4s and a Willoughby, Ohio, address.

If you are not averse to having solidstate devices in your signal path, an EP-3 would be a fine choice for players looking to purchase an Echoplex but not wanting to pay premium prices for a tube model. In most setups, the differences would be minimal and these units can be found for not much more than a new digital pedal.

EP-4 (late 70s): Around 1976-’77, the Market Electronics/Norlin team introduced another model, without S.O.S., but having bass and treble controls for the echo signal. The four-segment LED recording level meter, a control panel-mounted record level knob and separate microphone input and PA mixer output jacks were other new additions. The EP-3 and 4 were offered concurrently and at the same price ($489.95) in the late ’70s, but C.M.I. may have been unloading old EP-3 stock.

Mike Battle claims he was not involved in the EP-4 and sites a few problems in the design. One involved adding a noise gate that could be heard cutting the signal off as it approached full decay. Both Dixon (who was not involved in the testing of this model) and Clay (who turned his EP-2 in for a brand new EP-4) have proclaimed their distaste for this feature.

Another post-Battle failure in the first EP-4s involved Don Dixon suggesting a compressor be added to the record section so a stronger average signal would yield less distortion from peaks and therefore, a higher signal-to-noise ratio. He had the company’s engineers hook up an inexpensive stompbox into the signal path leading to the record head and the results were reportedly a noticeable reduction in tape hiss. Unfortunately, the finished unit was rushed into production without Dixon testing it. The compressor had been added to the entire signal – wet and dry – causing a furor from players. The units had to be recalled and the compressors removed, bringing an end to Dixon’s “improvement.” Although he tried to explain they went about it the wrong way, his idea was dismissed by soured management. This “new and improved” model marked the beginning of the end for the Echoplex.

Other Models

ES-1 Sireko (early-to-mid ’70s): Pronounced sir-echo, this entry-level model was introduced around the same time as the EP-3. While C.M.I. claimed the only difference to be the lack of Sound-On-Sound, the tape cartridge was considerably different, with extra tape loosely run inside a clear, boxy section. Unfortunately, these cartridges are no longer available, making the purchase today of a Sireko a risky maneuver (see “Maintaining Your Echoplex,” step 9). The physical length of the delay time’s “throw” was smaller than the EP-3’s, offering less control; otherwise, it was probably a decent unit for the time. And it was more than $100 cheaper!

EM-1 Groupmaster (early ’70s): While the bottom-of-the-line Sireko was offered into the second half of the ’70s, the top-of-the-line Groupmaster was not. The short-lived, Battle-designed, Dixon-approved model was equipped with four channels, each having two inputs, a volume and tone control, and a switch to send signal into the master echo section, if desired. The operations were similar to an EP-3, having controls for the number of repeats, echo mix, delay time, and record level. Sound-On-Sound and playback were available and a large VU meter added a visual reminder to maintain volumes, giving the unit a professional look for the time.

Harris-Teller Models (late ’80s): Following the late-’70s demise of Maestro by Norlin, Market Electronics was left to find distributers for its product. One of its largest accounts was the Chicago-based wholesaler, Harris-Teller. These units say “Echoplex” on the front instead of “Maestro.”

With the death of Bob Hunter, the Echoplex division of Market Electronics (and related trademarks/patents) was sold to Harris-Teller around 1984. Manufacturing was jobbed out to a local electronics concern, Crystal Valley Electronics, which used existing parts inventory to build a run of the EP-2, EP-3 ($550) and EP-4 ($550) models. The limited edition EP-2 reissue was called the EP6T ($739.50) and like the original, was all-tube. All three appear similar to the Market Electronics models, save for a “Quality Product from Harris-Teller” tag. Units were sold starting in the Spring of ’85 and the company was still selling its stock of EP-4s as late as ’91, although demand and awareness from the public had diminished. It still has a large inventory of selected parts that can be ordered through music stores, although you may want to check availability first by writing Harris-Teller, 7400 S. Mason St., Chicago, IL 60638. There are no circuit boards or cases, but motors, heads, and many of the specialty parts are in stock.

Jim Dunlop (’90s): While Jim Dunlop has not yet offered an Echoplex to join the company’s line of reissue Cry Baby, Uni-Vibe, Dallas-Arbiter Fuzz Face, Heil Talkbox and MXR pedals, the rights to use the name and designs were purchased from Harris-Teller a few years ago. Considering Dixon’s interest in a reissue tube model, Battle’s efforts using up-to-date parts, Dunlop’s success with modern versions of classic effects, and the fact they’ve been talking among themselves, it’s possible there may be another Echoplex by the end of the century, though that’s purely speculative. If your local music store doesn’t stock replacement tapes, you can order them from Dunlop, (707) 745-2722.

Tubeplex (late ’90s): Mike Battle has worked on things electrical his entire life – everything from one-tube radios to transmitters, remote control military planes, weather radar, televisions, air conditioning systems, and musical equipment. He has worked for the federal government, Goodyear, and Ford, and has operated his own shop and been involved in a serious partnership on the other. A lot of this work has revolved around earning a living to support his family, but the amount of time and energy extended to learning and staying on top of technology implies a desire to do more than just keep a job. Out of all he’s done, it’s apparent that being involved in the world of musicians is where his heart is and his devotion to perfecting the Echoplex appears to be a lifetime ambition.

While still in the development stage, his new Tubeplex is a marriage of the concepts behind the Echoplex and the world of analog electronics. Musicians familiar with the Echoplex will find comfort in similar controls and operation, including the sliding head to adjust delay time and the single echo/instrument balance control. There’s a knob for the repeats, but now it can be overridden with a foot pedal, allowing players to crank the regeneration as the original signal decays. Another guitar-friendly addition a second playback circuit with a separate head just after the record head, mounted to the sliding mechanism and providing reverb to the original signal in addition to the adjustable echo.

Of course the signal path is all tube, using the more-accessible 12AX7 twin triodes in place of the discontinued 6EU7s of the originals. Using a third 12AX7 for the bias oscillator in place of the original 6C4 leaves a stage available for a cathode follower output, a nice touch. Noise reduction has been added to the record section to reduce tape hiss without effecting the original signal and line-level echo out gives the user a 100 percent wet signal to do with as desired. Although the standard tape cartridge and its time-tested path are throwbacks to the earlier units, the VCR motor and capstan/pinch roller are up-to-date and readily available.

If only so Don Dixon can continue to do his twin guitar tricks, the playback footswitch has been included. With tape length having grown from approximately two minutes on the original to around four in modern times, a bit more patience is required before the electrical partner starts in. And while Dixon is not involved in the actual development and business end of the new product, he has lent Battle and his project the use of his highly trained ears a few times. Somehow, after 40 years, this only seems appropriate, even if it’s just for old times sake.

The unit has been designed so mass production is feasible, but currently the Tubeplex is still in its handmade prototype stage. For those interested in hearing more about a future Tubeplex, Battle can be contacted at his home/shop in the Eastern time zone, (330) 794-0939.

Postscript

Considering the title of this column is “Vintage Guitar Amplifiers,” some may have found the last four installments on echo devices a bit extravagant, testing the limits of what an amplifier really is. In defense of these tone-manipulating devices, they aren’t guitars. And they all act as preamps, with the EchoSonic also having a power amp section and a speaker.

Remember, playing guitar through an amplifier isn’t just about making the instrument louder, or we’d all be playing through 1,000-watt Crowns with a volume pedal! It’s also about taking the unique qualities of the guitar and embellishing them.

Something to consider is that the use of echo, and later reverb, goes hand in hand with the popularity of the electric guitar and amplifier. Yes, players were using electric guitars long before Les Paul’s friend put that playback head after the cutter, but the sound was not making the big impression in the music world that the sustaining vibrato tones of the electric Hawaiian guitar were. The ratio of Hawaiian to Spanish electric guitars sold prior to musical echo certainly backs this up. As does the popularity of recordings with the guitar up front that followed, from Les Paul and Chet Atkins, with their heavily echoed notes all through the ’50s to the reverberations of Duane Eddy at the close of the decade.

Taking Eddy’s musical premise that if your electric guitar sounded big, you could get away with playing simple licks, countless surf bands kickstarted the electric guitar’s next decade. In Europe, Hank Marvin was having a similar effect on young players and record buyers with his Meazzi-powered melodies. Commercially available echo and reverb for the common manmade sales of electric Spanish guitars climbed exponentially during the ’60s. With the right tone, even a kid starting out could sound good.

This isn’t to say the “in your face” sound popularized by Charlie Christian and followed by the legions of pure-toned jazzers that have followed wouldn’t have been as successful. But this style depends on having no small amount of technique and a great deal of musical background; the notes have to be going somewhere, you can’t stop and revel in the sound of what’s coming out the speaker. The lyrical playing of a cellist or horn player simply cannot be captured on a Spanish guitar without using effects. And let’s face it, a dry tone is just not as much fun. Long live the big wet twang!

Thanks this month go to Dave Howe of Harris-Teller for all his efforts, Jim Dunlop, Bill Victor, John Peden for the extended loan of his EP-1, and of course Don Dixon and Mike Battle for their stories.

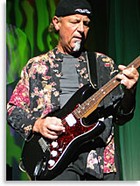

John Teagle plays guitar for the NYC-based instrumental combo the Vice Royals, and is the author of books on Fender amps and the history of Washburn/Lyon & Healey. Currently in the works is Plugged In: Electric and Electrified Musical Instruments, 1900-1950. Correspondence welcome c/o VG or e-mail teagle2@compuserve.com.

Greybox EP-1 Serial No. 606, courtesy of John Peden. Photo: John Teagle.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Oct. ’98 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

.jpg)