The biting snarl of Michael Monarch’s Fender Esquire was one of the trade

The biting snarl of Michael Monarch’s Fender Esquire was one of the trade

Can you truly put a price tag on peace of mind? For guitar collectors, the answer often is “No,” because like many other increasingly valuable collectibles, vintage guitars cannot be replaced.

So it is that we record, photograph, catalog, and insure our collections so that if they’re stolen, we’ll have as much info as we can possibly lend Johnny Law and the guitar community to aid in the recovery of our stuff.

But what if the unspeakable happened? What if one’s house was destroyed? If you keep your guitars at home, and they’re particularly valuable, you might want to consider one of the security solutions unveiled at this year’s winter NAMM show.

Gibson’s String and Original Equipment Division Collector’s Vault is 900 pounds worth of serious peace of mind. At 60″ high, 40″ wide, and 28″ deep, the Vault is rated to provide 1,200 degrees of fire protection for 30 minutes – certification included.

But unlike a standard safe, this one offers deeeeluxe velvet-soft accommodations for up to nine guitars, complete with interior lighting, electronic dehumidifier, and a drawer for documentation (insurance records, etc.), all in a high-gloss black finish with silkscreened Gibson logo.

While modern safes typically employ keypad lock/entry systems, the Vault sports a classic-look heavy-duty tumbler combination lock chosen for its aesthetic appeal. Underwriters Laboratories gives it a burglary rating of “residential security container.”

Gibson’s price includes “tailgate delivery” to a ground floor location. A power dolly is required, so if you plan to use the vault somewhere other than the ground floor, the customer has to make necessary arrangements.

Insurance is one thing, but vintage guitars are irreplaceable. The Gibson Collector’s Vault offers peace of mind beyond “replacement cost,” and gives the serious collector an option beyond the piece of paper that is an insurance policy.

Ralph Stanley prefers to call his “Mountain Music” rather than bluegrass or country. This moniker also aptly describes the material on Dolly Parton’s new album. Halos and Horns, her third release on Sugar Hill, differs from her last two because it’s self-produced.

And instead of being populated by A-list session players, it features the musicians Dolly regularly tours with. Their musicianship, while still first-rate, is perhaps a bit more sensitive to the mood. Overall, the album has more of an old-time country string band feel and less of a revved up high-octane bluegrass edge.

Twelve of the 14 tunes are Parton originals, and the two covers are odd bedfellows. David Gates “If” originally recorded by Bread, shares space with the Led Zep epic “Stairway to Heaven.” Dolly makes both seem as if they were written for her. Her “Stairway to Heaven” will drive the original out of your brain after one listen. Her voice soars in a way Robert Plant’s never could.

Her own songs cover an equally wide array of moods and idioms. The title cut nails ’50s honky tonk, while “Shattered Image” boogies, driven by a bluesy dobro obligato. On the most “cinematic” song, “These Old Bones,” she uses two voices to represent the principal characters in the story. Her old crone voice is most effective. My favorite track, “Dagger Through the Heart,” features great double-stop mandolin work by Brent Truitt.

So much country music is merely repackaged pop-rock with fiddles and dobros instead of synthesizers and Marshall stacks. Real country – where feeling and emotion predominate, like on Halos and Horns – makes it clear that authentic country is not only more powerful, but more lasting than anything you’ll hear on country radio’s hit charts.

Jackie King’s pretty much done it all. Born in Texas, the son of a guitar player, his path took him from playing in bars at age 13, to hanging out with legends in late-’60s San Francisco, to playing amazing solos behind music legend Willie Nelson.

You may have spotted King on some of Willie’s early-’80s TV appearances; he was the lefty guitarist who looked like he was enjoying himself to no end, ripping through incredible jazz solos where you’d least expect them.

A couple of years ago, King released Moon Magic on Indigo Moon Records. It gave him a chance to show off his incredible chops and soul. Truly one of the great jazzers around who still plays standards, it’s a treat to hear him play. And earlier this year he and Willie released The Gypsy (also on Indigo Moon), an intriguing mix of country and jazz with King spotlighted on most cuts and Willie playing some fine guitar and singing on a couple of tunes.

King is about as personable and friendly a guy as you’ll meet in the music biz. Naturally, we started with Willie and the new album.

Vintage Guitar: You’ve played with Willie, on and off, for a long time? What possessed you to make this record at this time?

Jackie King: Well, we’ve had this mutual respect for a long time. We had some of this stuff we did several years ago, and some of this stuff we did just a few months ago, so we’ve been putting it together for awhile. The idea was to make a country/jazz/swing connection (laughs).

Trying to show where everything meets, in other words?

Exactly.

The tunes are certainly an interesting mix. Do you guys actually perform any of those songs onstage?

Yeah, we do “The Gypsy,” and a lot of standards. The tunes were selected because they were the songs that both country swing guys and jazzers were doing. The bebop players were taking tunes like “Back Home in Indiana” and “Lover Come Back to Me,” and writing jazz heads at the same time the country players were doing them. You know, like “Cherokee” was Ray Price’s theme song for years. And guys like Buddy Emmons, we were all playing together for years.

I mean, guys like Horace Silver and Clifford Brown were doing “Quicksilver,” which is the same tune as “Lover Come Back to Me.” So the tunes were just songs that literally everybody was doing.

You’re out again with Willie. What do you use for guitars on the road?

My Gibson Byrdland, for the most part, is still the axe. I don’t like to fly with it, for obvious reasons. When we start a branch of the tour, we fly, and we fly when we leave. But very rarely do we fly during the tour. We bus it. So, I generally get the Byrdland out and take it with.

Historically speaking, I first ran into you on some old “Austin City Limits” episode from the early ’80s. You were always sitting behind Willie, smiling, they suddenly you’d play a jaw-dropping solo. You remember anything about those?

Yeah, there was one that was a tribute to Django. Plus some roundtables that were a lot of fun.

Let’s go back a little before that. How’d you start?

Well, even when I was a kid, I was completely audible. I have a lot of problems with things like maps (laughs). My dad played guitar, and I always wanted to play. Of course I was left-handed, so he re-strung everything for me. I actually started on mandolin. I was about eight then. I loved the guitar so much.

My dad taught me the first stuff, and then I studied with a player named Spud Goodall, a wonderful guitarist in San Antonio. He’d played with Bob Hope and knew Les Paul, who I thought was actually playing all those tracks at once! People ask me how I learned to play so fast; I thought Les was doing it, so I could too!

Were you a jazz fan that young?

Yeah, San Antonio was a big entertainment town, and there was a big mix of things. There was country swing and jazz. Bob Wills and everybody else was putting their own spin on things.

So, country musicians were doing jazz. Some great players were playing in that area. Also some great R&B in the area… Gatemouth Brown was there, and nobody knew who he was! He was playing the Eastwood Country Club after hours. And T-Bone (Walker) was there. So the mix was great.

Did your professional career start pretty early?

Oh yeah, when I was 12 I was playing five nights a week.

Gigging regularly at 12?

Yeah, I told ’em I was 13… I thought that made a difference (laughs)!

You moved to San Francisco in the late ’60s. Was that a musical move?

Yeah, me and Doug Sahm grew up together and ended up out there. At the time, everybody was into the psychedelic stuff, and Doug talked me into coming out. He’d already had a couple of big records.

I went out, and we formed a little band with some studio musicians. It was experimental, as you might expect. Very fusiony in the true sense of the word, with the mixture of rock, blues, jazz, eastern, and anything else we could think of. So we formed a group called The Shades of Joy and we did a couple of albums with them. I did some studio work at the time too.

By the time the ’70s rolled around, you were doing lots of gigs…

Yeah, I did everything I could. We’d put a band together to back up folks who came to town. I also played with Chet Baker for about a year.

Did you record with him?

You know, I did… We recorded two live performances that haven’t been put out. Maybe someday we can, since it’s two things with Chet that have never been heard. We’re trying to figure out some way to do that.

How about your career as an educator? How’d that all come about?

Well, I’ve always taught, and always loved it. Howard Roberts would come to San Francisco, and he asked me to do some clinics. Then he asked me to come to GIT, which he was just opening, to teach. So, I taught there for a year. Then I went back to San Antonio and opened a full-time guitar school called The Southwest Guitar Conservatory. That was very successful. We had people from all around the world. I closed it after about seven years because I got so busy playing with Willie and other folks.

Recording-wise, you seem horrendously underexposed. What have you done?

Well, I did an album for CBS called Nightbird. It’s funny, we were recording it at Willie’s studio and l said, “Grab your guitar and play a little bit.” It’s a jazz album with a little different sound. It’s got a Native American theme with jazz arrangements. It’s funny, though, ‘cuz it’s a jazz album and you look at the credits and all of a sudden you see Willie Nelson’s name. I also did an album called Skylight for an obscure label called Texas Record. That was in the ’70s.

Since you’ve obviously been around the industry a long time, could we get some impressions of folks from you.

Sure, go ahead…

How about T-Bone Walker?

Just a very, very down-to-earth guy. As musicians, we had that kind of common bond where everybody’s kind of the same.

Chet Baker?

Chet was a wonderful person.

You’re a Texas guy. How about folks like Stevie Ray?

Oh yeah, he’d come and see me play, and I’d go and see him play. He was just one of those great Texas guys.

Gosh, there’s so many…

You spent all that time in the ’60s on the West Coast. How about Jerry Garcia?

People, at that time, were always playing together, so Jerry and I did some stuff. Mike Bloomfield, Rick Derringer, they’d all come through and we’d play.

Rick must be a heck of a guy. He sent me a nice note and a signed photo, just because I reviewed a re-release of his a few years back.

Yeah, I remember sitting with Rick one time… remember the old Echoplex? It was a great piece of equipment. Well, I remember Rick had just gotten one, it was a new thing, and we stayed up all night just foolin’ with it. Very nice guy, and a very good guitar player.

How about Howard Roberts? Others?

Howard was a wonderful guy. Herb Ellis is a great guy. I’ve done some gigs with him. He’s a legendary character among guitarists.

If you’re sitting around at home, what do you listen to?

I might put on almost anything, but what I’ve been trying to do lately, with all the re

This is Melvin’s fourth record for the Evidence label, and like the rest, it’s a showcase of his dazzling technique and deep soul. This guy is a treasure. Perhaps it’s because he’s hard to pigeonhole. He’s definitely a blues player, but he’s not afraid to turn it up, step on the wah and let ‘er rip. Maybe that makes some of the purists cringe, but it shouldn’t.

Most everything here is a cover; B.B. King’s “Help the Poor” features Melvin lifting the Robben Ford arrangement from the late ’80s. And his playing sings over the proceedings. Nasty licks, and even a few “Robbenisms” make it a real guitar-fest type of song. The jazzy instrumental “Comin’ Home Baby” lets him show off some chord and octave work that would be welcome in any jazz club. And the chorused solo out is wonderful in its tastefulness.

In that same vein is “Eclipse,” which has some soulful playing, paying homage to Jimi along the way. Stephen Stills’ acoustic chestnut “Black Queen” is turned into a fiery electric blues with Melvin’s guitar leading the way. There’s even a re-make of Z.Z. Top’s “Blue Jean Blues” that makes the tune seem written for Melvin.

Scorching solos and plaintive vocals are everywhere. For “I’m the Man Down There,” Melvin pulls out the trick bag. The horn-driven blues lets him show off the chops and versatility, and he doesn’t disappoint. Vocally, Melvin is more than adequate. He’s not a blues shouter with the huge voice, but everything he sings is soulful and heartfelt.

I’m amazed Melvin doesn’t garner more attention. He’s got the chops, the pedigree, and most importantly the heart and soul. His band cooks, helped by the wonderful Lucky Peterson, who splits his time between B-3 and guitar on the entire CD.

Dallas-based Teddy Morgan was a protégé of the less-is-more master Anson Funderburgh, whose rhythm work can be heard throughout this release, and to a large degree Morgan is still immersed in Anson’s style.

Careers have been established with much less influence, but Morgan and the Crawl did not stop there. He has been busy over the last seven or eight years absorbing many influences including the great swing stylists Al Casey Tiny Grimes and Bill Jennings.

Having counted on the vocal and harp talents of Lee McBee, Morgan has undertaken a big responsibility choosing to handle the vocals. This is good to hear; it illustrates his efforts to find his own voice, instrumentally and vocally. While he doesn’t present the depth of emotion that McBee does, he maintains a journeyman’s quality to his presentataion, and I applaud him.

Morgan is writing and playing as well as ever, and singing his own material. That distances him from the pack. And we’re fortunate to be privey to this bold undertaking by a young player tackling the traditon, the way it should be.

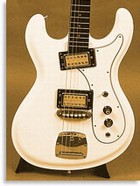

Ca. 1974 or ’75 Univox Hi Flyer Mosrite copy with the later Univox see- through humbuckers.

While most think of the history of American guitars in terms of American manufacturers, if you’ve followed this column you know the tradition is much richer. Among the major players in the American market were the many importers and distributors who enriched the guitar landscape with instruments – usually at the lower ends of the market brought in from other countries, primarily from Europe, Asia, and to a lesser extent, Latin America. The analogy with automobiles is obvious. While we tend to think of the automobile industry in ethnocentric terms, it’s impossible to think of “cars in America” without considering Volks-wagen Beetles, Toyota Corollas or Datsun Zs (Yugos and Renaults deliberately ignored).

One name that comes to the mind of anyone who has looked at guitars hanging on racks is Univox, a name generally associated with the “copy era” of the ’70s. Univox was one of the first brands to make copies, and the brand achieved a fair amount of national visibility and distribution.

Univox was not, as you might guess, just another isolated Japanese import, but was part of a much larger story of its importer, the Merson company. And in this context, Univox is a part of the much larger story that included names you probably see everywhere but know little about, since they’re off the beaten path, names such as Tempo, Giannini, Westbury, Korg and much more! You’re going to have to pay attention here, because a whole bunch of familiar and not-so-familiar names crisscross through this story.

Unfortunately, not many reference materials are available to document in complete detail, but we can hit some of the highlights, and illuminate a number of relationships along the way. If you have catalogs, ads or pictures of guitars that can help fill in some of the blanks, please let me know (Michael Wright, PO Box 60207, Philadelphia, PA 19102).

Tempo

Merson was a distribution organization founded by a man named Bernie Mersky. At some point, Merson was taken over by Ernie Briefel. Little more is known of the origins of Merson, but it was already marketing Merson-brand archtop electric guitars and amplifiers in the late ’40s, when the company was located in New York City.

The first Merson guitar advertised in The Music Trades appeared in the December, 1948, issue. This was the Tempo Electric Spanish Guitar which listed at $59.50 plus $11.50 for a Dura-bilt case. The Merson Tempo was an auditorium-sized archtop with a glued-in neck, a harrow center-peaked head which looks almost Kay. The guitar was finished in a shaded mahogany with a pair of widely separated white lines around the edges. Available source material is hard to see, but these appear not to have any soundholes. The fingerboard was probably rosewood with four dots (beginning at the fifth fret). This had a typical moveable/adjustable compensated bridge, elevated pickguard and cheap trapeze tailpiece. One Super-Sensitive pickup sat nestled under the fingerboard, and volume and tone controls were “built-in.”

Accompanying the Tempo guitar was the Merson Tempo Guitar-Amp. This was a tube amp with two instrument and one microphone input, heavy-duty 8″ Alnico 5 speaker, volume and tone controls, and a pilot light. The cabinet was covered in two-tone leatherette. The picture is in black-and-white, but the look is remarkably like Premier amps of the time, so a tan and brown color would not be a bad guess. The speaker baffle featured a classical guitar design (!) with “Tempo” written in little circles on the bridge! Substitute a lyre for the classical guitar and you’d swear this was a Premier, made by Manhattan neighbor Multivox, so that might, indeed, be the story there.

No information beyond this debut is available. It’s also probable the Merson “Tempo” name was applied to other acoustic guitars. Merson instruments from this period do not appear to have been widely distributed, so they are probably a regional phenomenon, although they did get notice in The Music Trades, a major trade publication. Other instruments distributed by Merson in 1948 included Harmony, Kamico, Favilla, Temp and Supro electric guitars and stringed instruments; Covella, Fontanella and Galanti accordions; Tempo Bandmaster, Merson, Merson Ultratone, and Rudy Muck brass instruments; and Kohlert Thibouville, Freres, Penzel-Mueller, Barklee and Merson woodwinds.

It’s not known how long these early Merson Tempo guitars and amps were offered, but into the early ’50s might be a reasonable guess, although the name was still in use on some low-end import guitars and amps as late as 1971.

If you find a ’60s Japanese import with a Tempo name, you will know from whence it came.

Tempo guitars and amps offered in 1971 included three nylon-stringed guitars, three steel-stringed guitars, and two solidstate amplifiers. These were pretty low-end beginner guitars probably imported from Japan, though the heads have a Harmony look to them. The N-5 Folk Guitar ($31.90) was standard-sized with spruce top and mahogany body (presumably laminates), slothead, tie bridge, no markers. The GM-62 Steel String Guitar ($29) was also standard size, “light” top and “dark” back with dots, moveable bridge with saddle and stamped metal tailpiece. The GM-300 Convertible Guitar Outfit ($33.90) was a spruce and mahogany slothead with dots and a glued/bolted bridge which could be used for either nylon or steel strings. It came with nylons and an extra set of steel strings. Harmony made guitars like this for Sears in the early ’60s. The N-48 Nylon String Guitar Outfit ($82.50) was a grand concert classical with amber spruce top, maple body, marquetry strip on the slothead and gold hardware, hardshell case included. The N-40 Nylon String Guitar ($45) was grand concert-sized with amber spruce top and “dark brown” body. The F-34 Steel String Guitar was also grand concert-sized with spruce top, “dark brown” body, belly pin bridge, block inlays, and engraved hummingbird pickguard.

Two solidstate Tempo beginner amps were offered in ’71. These had black tolex covers, front-mounted controls and a rectangular logo with block letters on the grille. The Tempo No. 158 ($65) had an 8″ speaker, 10 watts of power, tremolo with speed control, reverb with depth control, three inputs, volume, tone and a black grillcloth surrounded by white beading. The Tempo No. 136 ($31.50) offered a 6″ speaker, six watts, three inputs, volume and tone. The grillcloth was dark (probably black) with horizontal flecks.

It’s not known how long the Tempo guitars and amps lasted, but if they got far beyond ’74 it would be a surprise, and they probably didn’t survive the breakup of Merson and Unicord in ’75. Tempo guitars are not seen after ’76.

Giannini

Merson emerges again as an importer in the late ’50s and early ’60s (as the guitar boom was building), marketing Giannini acoustic guitars made in Brazil and Hagstrom electric guitars made in Sweden. Recall that in the ’50s, the accordion craze had given great impetus to the success of music merchandisers. But by the end of the decade, the collapse of the fad left them holding the squeeze-box, as it were. After some meandering, the Folk Revival picked up at the end of the decade, creating a growing market for acoustic guitars. Hence the Gianninis.

Giannini guitars were (and are) made by the Tranquilo Giannini S.A. factory, Carlos Weber 124, Sao Paolo, Brazil. They are generally known for being well-made instruments featuring very fancy Brazilian hardwood veneers, as well as for the strange-shaped asymmetrical CraViola models. Probably the most famous, indeed, perhaps only famous, endorser of Giannini guitars was José Feliciano. No reference materials were available on the early Giannini guitars. A catalog from 1971 is available, with a snapshot of the line that probably goes back at least a decade, and certainly forward.

In ’71, the Giannini line was divided into three groups, the Classics, the Folk and Country Westerns, and the CraViolas.

Six slot-headed Classics were offered. The 133/8″-wide GN50 Standard ($65) had a yellow spruce top and mahogany neck and body. The 141/4″ GN60 Concert ($79.50) featured yellow spruce top and Brazilian Imulawood body. The 143/4″ GN70 Grand Concert ($99.50) sported yellow spruce and figured Brazilian fruitwood. The 15″ GN80 Auditorium (4109.50) was the same as the GN70 but with 4″ X 403/8″ dimensions. The 141/4″ GN90 Concert featured yellow spruce top and Brazilian rosewood body, with extra binding. The 14 1/2″ GN100 Grand Concert ($169.50) came in yellow spruce, Brazilian rosewood and ornate inlays. Cases were extra.

Likewise, six Folk/Country Western guitars were offered, with flat, corner-notched heads, belly pin bridges and tortoise pickguards. The 14″ GS240 Concert ($79.50) was a Spanish shape with natural spruce top, mahogany body, and dot inlays, presumably on a rosewood fingerboard. The 15″ GS350 Grand Concert ($99.50) was another Spanish with natural spruce and figured Brazilian fruitwood body, with diamond inlays and wood rope binding. The GS380 Grand Concert ($109.50) was the same as the GS350 except for a Brazilian rosewood body. The GS460 Country Western ($129.50) was a 16″ dreadnought with a spruce top in red sunburst, cherry-finished mahogany body, a black pickguard, sort of mustache bridge, diamond inlays and white binding. The 16″ GS570 Auditorium ($149.50) was another dreadnought with yellow spruce and full grained Brazilian rosewood body, diamond inlays and fancier rosette. The GS680 12-String Auditorium ($185) was another 16″ dreadnought 12-string otherwise the same as the GS570.

Three CraViolas were offered. These had a strange asymmetrical shape with a pear shape, no waist on the bass side and sharp waist (and almost cutaway taper) on the treble. Soundholes were D-shaped with fancy rosettes, with a pointed tortoise guard on the steel-stringed versions. These had slotheads with a Woody Woodpecker-like peak pointed bassward. The bridges were similar to the mustache version on the Country Western. The CRA6N Classic ($150) had a yellow spruce top and full-grained Brazilian rosewood body, no inlays or pickguard. The CRA6S Steel String ($160) was a similar steel-string with pin bridge and diamond inlays. The CRA12S 12 String ($175) was the 12-string version.

In about 1975, Ernie Briefel and Merson parted company with Unicord/Gulf + Western, becoming Music Technology Incorporated (MTI), on Long Island, taking the Giannini brand with it. Later, in the early ’80s, MTI would import Westone guitars made by the great Matsumoku company, which it would sell until St. Louis Music began its partnership with Matsumoku and, in 1984, transitioned its Electra brand to Electra-Westone and then ultimately Westone, which lasted until 1990, when SLM’s guitars all became Alvarez.

Whew! Sometime in the ’80s, MTI changed its name to Music Industries Corporation, which it bears to this day, still importing Giannini guitars.

The separation between Briefel and Unicord must not have been entirely unamicable, probably more a matter of direction than anything else. In any case, in 1978, following the demise of the Univox brand (when the Westbury brand was debuted) three Westbury Baroque acoustics were offered, all made by Giannini. These included one “folk” dreadnought with a tapered Westbury head, the stylized “W” Westbury logo, block inlays and a very Martin-esque pickguard. The “classic” was our old friend, the CraViola, with a new head shape. The 12-string was another CraViola. These probably only lasted a year or so; in any case, the Westbury name was dead by 1981.

Hagstrom

As the ’60s dawned, electric guitars began to increase in popularity again, and many distributors turned to Europe for suppliers. The Italian makers were the most successful, with EKO, imported by LoDuca Brothers, in Milwaukee, leading the pack. German makers were paced by Framus, which was imported by Philadelphia Music Company, located in suburban Limerick, Pennsylvania. The Scandinavian contingent was represented by Levin, Landola and Hagstrom, the latter picked up by Merson.

The first Hagstrom electrics actually came to the U.S. beginning about 1959, carrying the Goya name imported by New York’s Hershman (Goya acoustics were made by Levin, also in Sweden). These were the now-legendary sparkle-covered hollowbody “Les Pauls” with the modular pickup units. However, while the Goya acoustics continued on in the ’60s (eventually to be distributed by Avnet, the owners of Guild in the late ’60s), the Hagstrom electrics took on their own identity and switched to Merson. The first Hagstrom I guitars were the little vinyl-covered mini-Strats with the “swimming pool” pickup assemblies – basically two single-coil pickups mounted in a molded plastic assembly looking like its nickname, with sliding on-off switches and the Hagstrom fulcrum vibrato (which was also used on early Guild solidbodies). These were followed by similar wood-bodied Hagstrom IIs, then the quasi-SG Hagstrom IIIs in the ’60s. Hagstrom electrics continued to be imported by Merson through most of the ’60s, but by the ’70s distribution had switched to Ampeg, which was responsible for the Swedes, and several thinlines, some of which were designed by Jimmy D’Aquisto. Hagstrom hung around until the early ’80s before disappearing.

Oh, almost forgot. Martin eventually purchased the Levin factory and got the Goya brand name, which it uses to this day, but not on guitars made by Levin. Avnet eventually also sold Guild, which today is owned by Fender. Uh, um…

Univox amplifiers

Now we switch gears to a company called Unicord, which was owned by Sid Hack. At some point in the early ’60s (probably in around ’64), Unicord purchased the Amplifier Corporation of America (ACA) which was located in Westbury, New York, a northern suburb of New York City. ACA made Haynes guitar amplifiers and an early distortion device powered by batteries.

Unicord began marketing tube amplifiers made in Westbury, carrying the Univox brand name. It is quite possible this name was chosen to compete with the amplifier company located in Manhattan name Multivox, makers of the Premier brand name, although Multivox would not market amps under its company name until the late ’70s.

No reference materials are available to me for this early Unicord period of Univox amplifiers, but there was undoubtedly a line. These American-made amps featured tubes and use high-end Jensen speakers. The Univox logo was on the upper right corner of the grille on a large piece of plastic. The cabinet was covered in charcoal-flecked tolex with white beading, with a grey grillcloth. Front-mounted controls included two inputs, volume, tone, tremolo with speed and intensity, plus footswitch jack with footswitch. The jewel light on these early Univox amps was a little red square.

Gulf + Western

At some point, possibly in 1967 – please forgive the fuzzy chronology, – Unicord was purchased by Gulf + Western, the big oil/hospitality conglomerate. This was part the corporate acquisition mania rage of the mid-’60s which included deals for Fender (CBS), Gretsch (Baldwin), Valco (Seeburg), Kay (Valco) and Gibson (Norlin). Either just before or just after the Gulf + Western purchase of Unicord, Unicord was merged with Merson. It was probably then Merson moved from New York City to Westbury.

The new entity was known as Merson Musical Products, A Division of Unicord Incorporated, A Gulf + Western Systems Company, into the ’70s, probably until the split in around ’75 or so (we’ll come to that), after which the company would be known simply as Unicord, Inc., Musical Products, A Gulf + Western Manufacturing Company.

By 1968 (and probably with the union of Unicord), Merson and Gulf + Western, Univox amps had begun to employ a Japanese-made chassis in Westbury-made cabinets, still with the high-quality Jensen speakers. These combined tube output with transistorized components. They were covered with a black Rhinohide vinyl and sported a silver plastic logo with stylized block letters – initial cap with a little tail off the left followed by lower case letters – typical of the earliest imported Univox guitars, on the black grillcloth.

These amps were powered by two 6MB8 output tubes, an unusual configuration. Front-mounted controls included one guitar and two auxiliary inputs, volume, tone, tremolo (speed), and footswitch jack. The tremolo was a somewhat dodgy transistorized affair.

Almost identical models have been sighted in a dark grey covering, but it’s not known whether these fit earlier or later or at the same time in the chronology.

Solidstate

The movement to all-transistor amplifiers probably followed hot on the heels of the hybrid amps of 1968. The 1971 Univox catalog features a new, updated line of tube amps, but also has a little offset-printed flyer showing the Univox A Group of solidstate amps, which probably debuted a year or two before. These had black tolex-covered cabinets with vinyl handles, black grillcloths surrounded by white beading, and, on some, corner protectors. On amps with front-mounted controls, the logo had changed to wide, block, all-caps lettering printed on a metal strip running across the top of the grillcloth just under the panel. Combo amps with this logo treatment included the U-150R and U-65RN. The U-150R ($177.50) offered 20 watts of power running through two 10″ speakers, with reverb and tremolo, three inputs, and six control knobs. The U-65RN ($110) had 15 watts, one 15″ speaker, reverb and tremolo, with three inputs and five knobs. Joining these was the UB-250 ($150), a piggyback bass amp with 20 watts, 15″ speaker cabinet, two inputs, volume and tone. The U-4100 Minimax ($299.50) was a bass combo amp with 100 watts pushed through a 15″ speaker. Controls were on the back, with two channels for bass and normal. This had a rectangular logo plate on the upper left corner of the grille, with block letters and a round bullet or target design.

It’s not known how long this A group lasted – probably only a couple more years, except for the U-65RN. By ’76, the U-65RN was still around, now promoted with 17 watts, Hammond reverb, tremolo, 10 transistors, and a 12″ heavy duty speaker. This looked pretty much the same, except the logo was reversed in white out of a black metal strip above the grille and the power switch had changed. At some point, the U-65RN was joined by the UB-252 bass amp, offering 20 watts with a 15″ speaker, presumably similar and transistor. These are the only two Univox amps listed in a 1979 price list (contained in the 1980 book), though, as you see over and over, others may still have been available.

The Blues

In ’71, Univox introduced what are arguably their coolest-looking amplifiers, the B Group, covered in nifty two-tone blue vinyl. Remember, this was the tail end of the heyday of Kustom, with its colored tuck-and-roll amps, and the two-tone blue with a red-and-white oval logo was boss. The lettering was the same uppercase blocks as on the outline logo. These new Univox amps were hybrids, with solidstate power supplies and lots of tubes – lots! The Univox B Group had two combo and two piggyback guitar amps, two piggyback bass amps and a piggyback PA. It is not known how these were constructed, but because previous amps had Japanese chassis put into Westbury-made cabinets, these were probably built that way also.

’71 blue vinyl combo guitar amps included the Univox 1040 and 1240. The 1040 Guitar Amplifier ($480) was a combo sporting 10 tubes, 105 watts RMS, two channels, four inputs, volume, bass, middle, treble controls for each channel, presence, reverb, tremolo, footswitch, and two 12″ Univox Heavy Duty speakers with 20-ounce Alnico magnets (possibly Jensens). The illustration shows a grille with two small circles on top and two large circles for the speakers. It’s possible this had a pair of tweeters in the small holes, but the description doesn’t say. The 1240 Guitar Amplifier ($399.50) featured eight tubes, 60 watts, two channels with the same controls as the 1040, and four 10″ Univox Special Design speakers with 10-ounce ceramic magnets (again, sound like Jensens). The grille had four round cutouts.

The two piggyback guitar amps included the 1010 Guitar Amplification System ($605), which offered 10 tubes, 105 watts, two channels, four inputs, volume, bass, middle and treble controls for each channel, presence, reverb, tremolo, variable impedance, and a cabinet with eight 10″ Univox Special Design speakers with 10-ounce ceramic magnets and epoxy voice coils. The cabinet grille had eight round cutouts. The 1225 Guitar Amplifier System ($435) had eight tubes, 60 watts, two channels with the same controls as the 1010, and a cab with two 12″ Univox speakers with 20-ounce ALNICO magnets and 2″ voice coil. The grille had two large round cutouts with two small round cutouts on the sides. The amps had handles on the top, the cabs handles on the sides, to make life easier for your roadies.

The two ’71 piggyback bass amps included the 1060 Bass Amplifier System ($530), featuring seven tubes, 105 watts, two channels, four inputs, volume, bass, middle and treble controls on each channel, presence, variable impedance, and a cabinet with one Univox 15″ speaker with 22-ounce dual diameter Alnico magnet and 2″ voice coil, plus a fully loaded reflex cabinet with true folded horn principle (you ampheads may know what the heck that means!). The grille had two large square cutouts with rounded corners. The 1245 Bass Amplifier System ($385) offered five tubes, 60 watts, two channels with the same controls as the 1060, and two 12″ Univox speakers with 20-ounce Alnico magnets and 2″ voice coil.

Finally, the Univox 1085 PA Amplifier System ($1,035) was another piggyback with 10 tubes, 105 watts, four channels, eight inputs, external echo or equalizer connection, four volumes plus master volume, bass, middle, treble, presence, reverb with footswitch, and a cabinet with four 15″ Univox speakers with 20-ounce Alnico magnets and 2″ voice coils. It also had 12 high-frequency horns with crossover networks, usually used with two cabinets.

Shaft

Lastly, but not leastly, Univox offered a super amp head, the C Group, or UX Series, available with either a guitar or bass cabinet. These were promoted with a flyer that sported a muscular black model with naked torso looking for all the world like Isaac Hayes, the man behind the popular movie Shaft. The UX actually consisted of a UX-1501 Amplifier head and either a UX-1516 speaker cabinet for guitar use or a UX-1512 cabinet for bass. The amp was a mean two-channel S.O.B. with blue vinyl and handles. It was set up for lead guitar, bass or PA use, with two guitar inputs, two bass inputs and two mixer inputs. Its 140 watts were obtained with eight tubes – four 6550s, two 12AU7s and two 12AX7s. It had two volume and a master gain controls plus bass, middle, treble and presence controls. Power on and separate standby switches. Four speaker output jacks. The coolest feature was a “tunneling circuit” that allowed, near as we can tell, blending of channels, which meant you could pump up the bass on one and hyper the treble on the other, and combine them. For a little extra punch, you could throw a hi-boost switch, too. The UX-1516 guitar cabinet was a 150-watter. For bass, the UX-1512 was a 200-watt Reflex Speaker Cabinet. Cost for the guitar outfit was $1,400, for the bass outfit $1,450.

It’s unknown how long these blue vinyl wonders lasted. By ’72, new all-transistor amps were appearing, and by ’75 the look was definitely long. It’s possible they lasted just a year before they got the shaft.

Mad Max

Also joining the Univox amp line in ’71 (illustrated in a ’72 flyer) was the Univox U-4100 Minimax Amplifier, already showing a different style, with dark tolex covering but still the oval logo plate on the upper left of the grille, now covered in black with vertical “dotted” lines (surrounded by a white vinyl strip). The Minimax was designed for use with bass, organ, electric piano or guitar, but really was a bass combo amp. It packed 105 watts through a 15″ Special Design speaker with 27-ounce Alnico magnet and 21/2″ voice coil, powered by 11 transistors, no tubes. The back-mounted chassis had two channels with high and low inputs, plus volume, bass and treble controls for each channel. Recommended especially for keyboards was an optional UHF-2 High Frequency Horns unit with two horns for extra bite. The flyer for this amp was still in the 1980 Unicord book, but a ’79 price list no longer mentions it, and it was probably long gone, though some may still have been in stock.

Pre-split Univox amps

At least three other piggyback Univox transistor amps were introduced in ’75 – the U130 Bass Amplifier, U130L Lead Amplifier, and U200L Lead Amplifier, plus a choice of speaker cabs.

The U130 Bass Amplifier pumped out 130 watts with five inputs covering two channels (high and low each) and one input that bridged both channels. Channel 1 had volume with push/pull high boost, bass, middle and treble contour controls. Channel 2 had volume, bass and treble controls. Both channels had master volumes, plus two, four or eight-ohm output. Cabinet options included the UFO215 with two Univox Pro Mag speakers in a front-loaded horn cabinet, or the U215 with two 15″ Pro Mags in a “tuned duct” reflex cab.

The U130L Lead Amplifier was very similar except Channel 1 controls were volume, bass, middle, treble, and reverb intensity, Channel 2 was push/pull volume, bass and treble, both with master volumes. Lead cabinet options included the U412 with four 12″ Univox Pro Mag speakers, the U610 with six 10″ Pro Mags, and the U215 (described above).

The U200L Lead Amplifier was similar to the U130L except it offered 210 watts of power and was recommended for use with either the U412, U610 or U215.

While other Univox brand amps may have existed during this period, these are the only ones on our radar scope. The brand was still being put on amps as late as 1976, and all of the later amps were still in a 1980 binder, though by ’79 only two Univox amps were listed in the price list. Most likely, when the Univox guitars went away in ’77 or ’78, so did the Univox amps, but supplies probably continued to be available as late as 1980. Anyhow, this sets the stage for the next development in amps to which we’ll come back…

Early Univox electric guitars and basses

The precise chronology of the earliest Univox guitars is likewise uncertain.

These were possibly preceded by Tempo guitars – the brand used by Merson back in the late ’40s. As we said, in a 1971 catalog, Tempo guitars were offered, and it would not be surprising to find some mid-’60s Japanese guitars carrying that name, though we’ve not seen any.

Unfortunately, no reference materials were available for this early period, so we’ll make some educated guesses. Based on the evidence of the logo on the 1968 amplifier, we suspect Univox guitars with the plastic logo debuted at about the same time. By 1970, Univox was employing decal logos on some models, further corroborating this conclusion. If this assumption is correct, it would suggest that among the first Univox guitar was the Mosrite copy known later as the Hi Flyer, debuting in around 1968. This would be consistent with the evolution of “copies” in Japan. As the ’60s progressed, the Japanese were getting closer and closer to the idea of copying, producing guitars similar to their competitors, such as Italian EKOs and Burns Bisons, etc., finally imitating American Mosrite guitars in around ’68. The Japanese affection for Mosrites was no surprise, since the band most associated with Semi Moseley’s guitars was the Ventures, who were enormously popular in Japan.

The Hi Flyer was a thin-bodied reverse Strat-type with a German carve around the top, almost always seen in sunburst. This was identical to the Aria 1702T. The bolt-on neck had a three-and-three castle head, plastic logo, string retainer bar, zero fret, 22-fret rosewood with large dot inlays. A white-black-white pickguard carried volume, tone and three-way. Two black-covered single-coil pickups were top-mounted, the neck slanted back like on a Mosrite, with six flat non-adjustable exposed poles in the center. An adjustable finetune bridge with round saddles sat in front of a Jazzmaster-style vibrato. The plastic logo was still in use in 1971, though gone was the string retainer, replaced by a pair of little string trees. Dots had gotten smaller by ’71, and the Hi Flyer was available in three finishes – orange sunburst (U1800), black (U1801) and white (U1802). The Hi Flyer listed for $82.50 (plus $12 for case) in ’71.

Accompanying the Hi Flyer guitar was a Hi Flyer bass (U1800B). Except for having a bridge/tailpiece assembly and obviously four-pole pickups, these were pretty much the same as the guitar. By 1971, three finishes were offered – orange sunburst (U1800B), black (U1801B), and white (U1802B), for $99.50 plus $15 for a case.

The Hi Flyer guitar and bass would be offered pretty much until the end, in ’77. At some point after, probably around ’73 or ’74, the plastic logo was changed to an outline decal logo. Also, at some point the pickups were changed to the distinctive twin-coil humbuckers with metal sides and a see-through pink insert on top. These changes most certainly occurred by the ’76 catalog, when the Hi Flyers were available in four finishes – sunburst (U1815, U1815B), white (U1816, U1816B), black (U1817, U1817B) and a cool natural with maple fingerboard and black dots (U1818, U1818B).

I’m also going to go out on a limb and suggest the earliest Univoxes also included the ‘Lectra, a version of the one-pickup Aria 1930 violin bass (made by Aria). These were basically violin-bodied basses originally inspired by the Gibson EB-0, and popularized among imports by Paul McCartney’s use of the Höfner violin bass, copied by EKO. This was a hollowbody with no f-holes, Cremona brown finish, single neck pickup, bolt-on neck with position dots along the top of the 22-fret bound rosewood fingerboard. Strings anchored to a covered bridge/tailpiece assembly.

Controls were volume and tone. A little elevated pickguard sat on the upper treble bout. The earliest examples of these had the little plastic logo on the head. By ’71, these had changed to an outlined block letter decal logo. A fretless version was also available by ’71. The U1970 with frets, and fretless U1970F, were both $220 with case. How long these were available is uncertain, but they were probably gone by ’73 or ’74.

We don’t know about other early guitars, but Univox probably augmented its offerings with other offerings from the Arai catalog, similar to what Epiphone would do with its first imports slightly later, in around 1970. Evidence this might have been so is seen in the book Guitars, Guitars, Guitars (American Music Publishers, out of print) which shows a Univox 12-string solidbody with a suitably whacky late-’60s Japanese shape, with two equal cutaway stubby/pointy horns. The head was a strange, long thing with a concave scoop on top, and the plastic logo. This is the only example of this shape I’ve encountered, but it had two of the black-and-white plastic-covered pickups used on Aria guitars of the period, and the majority of later Univox guitars were indeed manufactured by Arai and Company, makers of Aria, Aria Diamond, Diamond and Arai guitars. These pickups have white outsides with a black trapezoidal insert and are sometimes called “Art Deco” pickups. Perhaps the coolest feature of this strange guitar is a 12-string version of the square vibrato system employed on Aria guitars of this era. You can pretty much assume that if there was a strange-shaped solidbody 12-string Univox, it was not the only model! These would not have lasted long, probably for only until 1970 at the latest, and are not seen in the ’71 catalog.

Copy era

Whether or not these guitars actually debuted around ’68 or a little later, we know for sure Univox offered one of the first guitars of the “copy era,” launched in ’69, the little bolt-necked Les Paul copy produced by Arai.

Shiro Arai, you’ll recall, attended the ’68 NAMM convention, where he saw the Gibson reissue of the Les Paul Custom Black Beauty. Aria and Univox Les Paul copies began to hit the U.S. market in ’69, accompanied almost simultaneously by the National Big Daddy, imported by Strum & Drum (not made by Arai).

The Univox/Aria Les Paul openly copied its American original, but would never be mistaken for it because it continued many characteristics typical of Japanese production at the time; a bolt-on neck with the usual narrow fingerboard, sitting relatively high on the body, zero frets, block inlays (with rounded corners) and rounded ends. The headstock was a copy of the Gibson open book. And, obviously, it didn’t have Gibson humbuckers, favoring instead a design with 12 adjustable poles in a metal cover with a narrow black insert slit in the middle, sitting on black surrounds. Controls were standard three-way with two volumes and tones. The knobs were those tall, skinny gold kind seen on many early Japanese copies. Hardware was gold-plated. These first Univox Les Paul copies survived into the early ’70s, but were probably gone by around ’74. By ’71, the model was called either the Mother or the R&B Guitar Outfit and was available in either black (U1982) or gold (U1983) finishes. Also by ’71, the Univox logo had changed from the early plastic version to the more common outlined block letter decal.

The Japanese copy juggernaut got off to a fast start, and the second major Univox guitar was the Lucy, a lucite copy of the Ampeg Dan Armstrong, again produced by Arai, introduced in 1970. This guitar had a surprisingly thin bolt-on neck (especially compared to the Ampeg original) and a slightly smaller body. The fingerboard was rosewood with 24 frets and dot inlays. This had a fake rosewood masonite pickguard with volume, tone and three-way select. Like the Ampeg, the Lucy had a Danelectro-style bridge/tailpiece with little rosewood saddle. Unlike the Ampeg – which had Armstrong’s groovy slide-in epoxy-potted pickups – this version had a pair of the chrome/black insert pickups jammed together at the bridge. Other Japanese manufacturers also made copies of the Ampeg lucite guitar, notably carrying the Electra (St. Louis Music) and Ibanez (Elger/Hoshino) brand names, with versions of the slide-in pickups. In ’71, the Univox Lucy (UHS-1) was $275 including case. Just how long the Lucy remained available is unknown, but it probably did not outlive the original and was gone by ’73 or ’74.

More copies

By ’71, the Univox had expanded considerably with new copy guitars. Still around from earlier were the Hi Flyer Mosrite copy, the ‘Lectra violin bass, and the Mother or Rhythm and Blues Les Paul copy. Joining them were the Badazz guitar and bass, the Effie thinline, another Coily thinline guitar and bass, and the Naked and Precisely basses. Univox acoustics are also first sighted (as far as we know) in ’71.

The Badazz U1820 guitar and U1820B bass were essentially bolt-neck copies of the new Guild S-100 introduced in 1970, the so-called “Guild SG.” This was a solidbody with slightly offset double cutaways. It had a bolt-on neck with a Gibson-style open book head, outlined decal logo, block inlays, bound 22-fret rosewood fingerboard (rounded end), two of the 12-pole humbuckers with the narrow center black insert, finetune bridge, Hagstrom-style vibrato (as found on early Guilds), two volume and two tone controls, plus three-way. The bass was the same without the vibrato and with dots along the upper edge of the fingerboard. These were available in cherry red, orange sunburst or natural (“naked”). List price for the guitars in ’71 was $199.50 with case, while the basses cost $220. These pickups, by the way, while being somewhat microphonic (as with most early Japanese units), scream, if you like a really hot, high-output sound.

The Effie U1935 thinline hollowbody ($220) was a bolt-neck ES-335 copy with a bound rosewood fingerboard, blocks, open book head with outlined logo decal, two 12-pole/slit humbuckers, finetune bridge, fancy harp tailpiece, three-way on the treble cutaway horn, elevated pickguard and two volumes and tones. The Effie was available in orange sunburst, cherry red or jet black. It is entirely probable an earlier version of this existed, since thinline versions of the ES Gibsons were already mainstays in Japanese lines by ’68. If you find one with the old plastic logo, don’t be surprised.

The Effie was also joined by the Coily U1825 guitar and U1835 bass. These were essentially the same except the Coily guitar had a Bigsby-style vibrato, roller bridge with flip-up mute, and a pair of chrome-covered screw-and-staple humbuckers, typical of early-’70s Arias. The Coily bass had similar four-pole screw-and-staple pickups and a fancy trapeze tail with a diamond design on it. These were available in orange sunburst, red and jade green. The guitar cost $122.50, the bass $135.

The two new Fender-style solidbody basses were the Precisely and Naked. The double-cutaway Precisely U1971 had a single pickup under a chrome cover, covered bridge/tailpiece assembly, Fender-style four-in-line head, dot-inlaid rosewood fingerboard, black-white-black pickguard with fingerrest, volume and tone. The Precisely had an outlined logo decal and a sunburst finish. The Naked U1971N was the same thing, natural-finished. Both cost $250.

At some point in this period, the pickups were changed to humbuckers with metal side covers and a see-through grey insert on top. I’ve estimated this changeover took place in about 1973 or ’74, but this is uncertain. Certainly it had been accomplished by ’76, when the next reference appears, so it could have been later (at the time of the Merson/Univox split in ’75?).

In ’74, Ibanez, which was by then leading the copy pack, followed the suggestions of Jeff Hasselberger and changed its designs by squaring off the end of the fingerboard and lowering the neck into the body to look and play more like a Gibson original. Virtually all Japanese manufacturers followed. Since Univox guitars were primarily made by Aria, it is probable that in late ’74 or ’75, Univox guitars also had these features, although the Gimme shown in a 1976 flyer still has the rounded fingerboard, and this was in a 1980 binder, so you can’t be too rigid in evaluating Univox guitars based on these details.

Three acoustic guitars were offered in 1971. These were glued-neck models with roughly Martin-shaped heads and pickguards slightly larger and squarer than a Martin. All had spruce tops (presumably plywood), mahogany bodies and necks, rosewood fingerboards and dot inlays. These appear to be Japanese, not Brazilian Gianninis. The bridges are glued on, with screw-adjustable saddles and pins. The U3012 Auditorium was a Spanish-shaped steel-string and cost $89.50 plus the cost of a case. The U3013 Grand Auditorium was a dreadnought costing $105. The U3014 Twelve String cost $120.

These early Univox acoustic guitars appear to have lasted for about four years, until 1975, when Merson and Unicord parted ways. It is possible other models were developed, but no reference materials are available.

Splitsville

We’ve already made numerous allusions to the “split” between Merson and Unicord, so now is probably a good time to talk about it. At some point (almost certainly 1975), Ernie Briefel of Merson decided to part company with Sid Hack’s Unicord. 1975 is the logical choice because flyers copyrighted 1975 are still identified as from Merson Musical Products, a Division of Unicord, Inc, a Gulf + Western Systems Company. All flyers from ’76 on are copyrighted by Unicord, Inc., a Gulf + Western Manufacturing Company. Briefel’s Merson subsequently relocated to Long Island and became Music Technology, Incorporated (MTI). This company took the distribution of Giannini guitars with it.

By the early ’80s, MTI was importing Westone guitars from Matsumoku, which had made its earlier Univox guitars (and the competitive Westbury guitars offered by Unicord). Wes-tone guitars continued to be distributed by MTI until ’84, when St. Louis Music, now a partner in the Matsumoku operation, took over the brand name and phased out its older Electra brand (also made by Matsumoku) in favor of Electra-Westone and then Westone. But that’s another story…

Following the breakup, Unicord continued to market Univox-brand guitars and amplifiers for a couple years, but the guitar world was about to undergo some fairly radical changes. We’ll pick up the rest of the Univox story, plus look at some of the other instruments sold by Unicord, including the Westbury brand, next month.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Feb. ’98 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

FEATURES

RIDING WITH LOS LOBOS

30 Years & Still Going Strong

Arguably the most important American band to come out of the 1980s, musically and sociologically, its contributions have secured the band’s place in the history of many styles. By Dan Forte

THE BASS SPACE

1960s Truetone Bass

This ’60s cheapo is the Western Auto house brand equivalent of a Kay #5915 and was, in its initial state, perhaps noteworthy for what it didn’t have – markers on the fretboard! By Willie G. Moseley

1929 Gibson GB-3 Guitar Banjo

Gibson’s Mastertone banjos arrived in 1925, boasting innovative features more suited for Dixieland music. In the hands of a skilled player, a six-string guitar banjo has a sound that rivals a good resonator guitar. By George Gruhn

THE BANGLES

Yesterdays… and Today

After a 10-year separation, the two-guitar band that rose to prominence in the 1980s with hits like “Manic Monday” and “Walk Like an Egyptian” reunited in ’99 to overwhelming response. By Kraig Sollenberger

JERRY SCHEFF

Before and Beyond Elvis

Best known for holding down the bottom-end in Elvis Presley’s fabled TCB Band, he has been a fixture in the recording scene for decades. And he has always done things his own way. By Willie G. Moseley

MARIAN HALL

First Lady of the Steel Guitar

Few, if any, women are mentioned amidst the legends of the steel guitar, but Marian Hall is one to remember. Her sound and style were vital to country, jazz and swing in the 1950s and early ’60s. By Cindy Cashdollar

THE DIFFERENT STRUMMER

Yamaha’s Full Metal Jacket

When you think of Superstrats, you don’t think of Yamaha. Nevertheless, it made some very nice examples of the form, in the shadow, perhaps, of its better known SG/SBGs. This is their story. By Michael Wright

DEPARTMENTS

Dealer News

Vintage Guitar Price Guide

Builder Profile

Butler Custom Sound

Upcoming Events

Vintage Guitar Classified Ads

Dealer Directory

The Great VG Giveaway ’04

Win a D’Addario/Planet Waves gear package!

Readers Gallery

FIRST FRET

Reader Mail

News and Notes

First World Guitar Congress, New Albums, Gibson Songwriting Contest, S.I.R Moves, Dr. Dylan, In Memoriam, more!

Barney Kessel 1923-2004

By Dan Forte

Executive Rock

Now Hear This…

By Willie G. Moseley

First Look! Clapton Throws a Party

Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Guitar Festival

By Dan Forte Photos by Eddie Malluk.

Classic Concerts

Elvis Presley

By Willie G. Moseley

BR549’s New Blood

By John Heidt

COLUMNS

Q&A With George Gruhn

Acousticville

Chinese-Made Mandolins

By Steven Stone

FretPrints

Barney Kessel

By Wolf Marshall

Gigmeister

Thoughts Are Things

By Riley Wilson

The Bitter Ol’ Guitar Curmudgeon

Guitar 101

By Stephen White

TECH

Dan’s Guitar Rx

Fixing Lil’ Junior, Part 2

By Dan Erlewine

Guitar Shop

Pimp My Guitar

By Tony Nobles

Amps

Five Ways to Preserve Your Vintage Amp

By Gerald Weber

Ask Gerald

By Gerald Weber

REVIEWS

The VG Hit List

Music and Book Reviews: Fleetwood Mac, Jimi Hendrix, The Pretty Things, Gurf Morlix, Thackery and Benoit, Blasters and Nat King Cole on DVD, more !

Check This Action

Uniquely American Music

Dan Forte

Vintage Guitar Gear Reviews

Gibson Cloud 9 Les Paul, Aiken Invader, Line 6 Variax Acoustic, Guyatone Flip Tube Echo, Floyd Rose Redmond Model One!

Gearin’ Up!

The latest cool new stuff!