Formed by guitarist Poison Ivy Rorschach and frontman Lux Interior, the Cramps emerged in the spring of 1976, offering up a unique and infectious sound that blended the early roots rock and rockabilly styles of the ’50s with the raucous punk sounds of the day.

Dubbing this new style “psychobilly,” the group built its cult following by playing popular New York City clubs like CBGB’s and Max’s Kansas City, then venturing West and spreading the music along the way.

Taking a cue from their musical influences, the group cut its first record, Lucky 13 (released in 1978), at Sam Phillips’ legendary Sun Studios.

Unlike most of the prevalent punk acts of the day, the Cramps had a twangy sound and an eccentric sense of humor. Their campy songs describe tales of horror, sex, Elvis, and other rock and roll fantasies. Although the Cramps have undergone a series of lineup changes through the years, the band’s inherent sound and style remained unchanged. This year, the group released its 13th album, Fiends of Dope Island (Vengeance Records), which includes a selection of new tunes and a few revered covers – “Hang Up,” “Taboo,” and “Oowee Baby.”

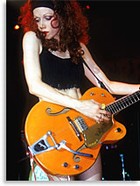

VG procured an interview with the lovely and talented Poison Ivy a few hours before the Cramps would obliterate crowds at a recent gig at Max’s Kansas City. She confessed her undying love for the ’58 Gretsch 6120 she acquired in 1985 and detailed her stage and studio rigs. Additionally, she revealed the basic formula behind the Cramps’ record-making process and explained how the music comes together.

Gentlemen, get on your marks and start your engines, please…

Vintage Guitar: Who were your original influences as a player?

Poison Ivy: I learned a little when I was young, but not a whole lot. My brother played some guitar and he taught me how to do “Pipeline” riffs and some chords, but other than that I’ve never had any lessons. I just started picking out songs on my own.

My most identifiable influences would be Link Wray and Duane Eddy. I think those guys seemed neglected when our band started. I loved Chuck Berry, but it seemed like early rock and roll was centered around Chuck Berry. So just the simplicity of it, the starkness – the stark chord of Link Wray and the stark single-note thing of Duane Eddy. There were a lot of obscure guitarists that I loved, like a guy named Don Gilliland, who worked with some artists on Sun Records. He’s the guitarist on the Slim Rhodes and Dick Penner records, but they don’t even say his name. It’s really strange and exotic, spooky stuff. I also loved Al Casey. His music is in the Duane Eddy vein, too.

Did those players influence your choices in gear?

Somewhat, in just that whole twangy sound. But I did start out with a solidbody, and I actually stumbled into a Gretsch hollowbody when the guitar I had was broken. I had this kind of rare Canadian guitar called “Lewis.” Actually, I had two of them. I bought the first on 48th Street in New York City in 1976, then the second in Vancouver in 1983. They’re both solidbodies with a Bigsby-like vibrato bars and they both weigh a ton. One unusual characteristic about both of them is that the necks are flat and wide, like a classical guitar. I wish I could find out more about them. When I bought the first one, the salesman told me it was a Canadian make. Well, the headstock on my main Lewis got snapped off at a concert in Paris. There was this riot, and a security guy grabbed it really fast… Actually, what broke it was him falling down the stairs with it!

That’s when I got my Gretsch, and I never turned back. That was ’85. I got a 1958 Gretsch 6120 and there’s just no going back. I’ve got other guitars including a Gibson ES-295 and some guitars I almost never touch. I have a Telecaster that I love. It’s great, but it’s just not my style. The Gretsch is my ultimate style.

Do you play other guitars onstage?

I have a 6120 reissue as a backup, for when I break a string. But the original Gretsch is my main guitar, and that’s all I play. It weighs a ton and I have heavy gauge strings on it, so it’s a struggle. But it just sounds so damn good!

I hesitate to take it out because it’s worth more than the reissues, but I just can’t get that sound with anything else. I’m too attached to it and it just kind of responds to me.

What type of strings and picks do you use?

I use D’Addario XL115 strings, which are .011-.049 gauge, and I use Herco gold picks because they’re the most versatile.

How do you like your guitars set up?

When other people pick up my guitar, they’re surprised by the heavy-gauge strings. The action is average, not real close. Being a hollowbody, I need it to really ring out. I play hard, so it would totally fret out if the action was too low. I have the pickups set close to the strings, so it’s pretty hot and kind of ripping.

Which amps and effects are you using in your live setup?

I use original blackface Fender Pro Reverb amps. I have two of them onstage – one is a backup. One’s a 2×12 and one is 1×15. I usually play through the 1×15. The Pro Reverb has built-in tremolo and reverb, but I use an outboard tremolo, too – a Fulltone tremolo pedal. I like the tremolo on my amp, but it doesn’t stay working for too long on the road, so I usually end up using the pedal. I also use a Univox Super Fuzz pedal and a Maxon delay for slapback.

Is that the same setup you used to record Fiends of Dope Island?

I use different amps to record. Those Fenders are roadworthy, but they’re too loud to record with. I play through small amps in the studio because the size doesn’t matter, just the overdrive and tone.

For recording, I mainly play through a tiny Valco amp with one 10″ speaker. It just sounds great and it’s got a great reverb in it. I have some other amps, too – I just got some new Allen amps right after we finished recording, so I didn’t get to use them. Allen is one of those Fender-inspired boutique companies.

I’ve also got an Allen Accomplice, which is a really cool amp, and an Allen Old Flame. I was going to take them on the road, but then I just chickened out. I was afraid they’d get trashed, so I’ll keep them for recording. They’re amazing amps.

Did you use an old tape echo in the studio?

No, that’s just the Maxon pedal. There’s no tape echo on the guitar, but there is a tape echo on the vocals. There are some modern delays that sound like a tape echo by degrading the decayed sound in the way that real tape would sound. So it comes back with less high-end. The Maxon is pretty effective in creating that sound. I think the impression is that it’s tape echo. But I’m sure there’s somebody that can tell the difference – if they’re discerning to the point of neurosis.

How do you typically set the controls on your amp?

On the Pro, it’s just treble and bass, with no midrange control. I have the treble set high, at around 9 or 10 – if I can get away with it – but it’ll squeal if I’m on 10 and using fuzz. I don’t use the bright switch anymore. I think I keep the bass at around six o’clock. I always have the reverb set so it’s barely on during soundcheck because whoever does the sound at the club will always say it’s too much. Rather than to argue with them about it, I just crank it up when I step out onstage.

In the studio, it depends on which amp I use and the song I’m playing. Sometimes I like the sound to be dripping wet with reverb, and then on other songs, I don’t want any reverb. It depends on the dynamics of the song and whether the guitar is to be banging or eerie.

It’s a compromise because echo is spooky, but it also softens the sound. I guess I want to have my cake and eat it, too. I want to be spooky and hard-hitting, but it’s hard to be both.

How many guitar parts do you typically record for each song? It sounds like there’s just one guitar on most of the tracks.

It’s usually one. I’m trying to remember if there was any overdubbing on this album… there may not have been any. We kept it pretty live. We even ended up using a lot of scratch tracks. If Lux is going for a scratch vocal, he always shoots for it being a main vocal and then, of course, it ends up being a main vocal. But with guitar, sometimes I can get better feedback if I crank the amp way beyond the point where I can also hear everybody else. So sometimes I’ll add a layer in back of the main guitar.

Does the band usually record together?

Yes. We can even see each other when we’re recording. It’s ideal. But we had a hard time in the first studio we used. We did “Wrong Way Ticket” and we thought what we got was the take. That song is especially hard on our drummer because there’s real athletic kind of drumming. After the take, the engineer, who was sort of distracted, said, “Oh man! The tape ran out!”

So, after wanting to murder him, we calmed down and had to just re-take that. There are certain songs that you can’t just punch in on. You just can’t. On “Elvis F***ing Christ” we had to re-take the whole song because Lux was going to punch in some vocal thing on the intro, and the engineer accidentally punched in on my guitar track instead. That song is such a freeform thing, and it isn’t structured in a way that we could have just punched in to fix it. It’s a call-and-response thing, responding to what the other guy is doing. We try to keep it all as live as we can, so we just had to redo it.

Describe the songwriting process. How do the songs generally come together?

It happens in different ways. Sometimes I’ll come up with a groove – a music thing – and that kind of inspires Lux. I’ll tell him that it reminds me of this or that, and then he’ll write lyrics for it. Other times he just has lyrics with no music. I’ll look at them and try to think of what mood would be appropriate for those lyrics. Sometimes we write together. Some songs come together in 15 minutes, and we’ll work on others for a month, deciding which parts could be better and which parts just aren’t working. It’s always different.

When we’re making a record, I always kind of freak out thinking we should do more stuff. I had this idea… I wanted to do a hoodlum version of “Taboo,” which was supposed to be a B-side. I had an instrumental idea with this fuzz guitar part, so I asked Lux to write some words while I showed the band what to do. He shut the door and came out 15 minutes later with lyrics. So we recorded it and did a rockabilly version of “Butcher Pete,” which is a Roy Brown traditional blues song. We just showed the band the key and what to do. Chopper [Franklin], who plays bass on everything else, played guitar on those. He played my spare guitar on “Taboo.” So those two came together very quickly at the last minute.

How was the experience different from making previous records?

I think the band was more on the same page. Chopper’s been with us for a year and a half, and Harry [Drumdini], our drummer, has been with us for 10 years, and he’s great. We all have kind of the same passion for rock and roll, and we can all relate to the same things. So if I make some reference to a Howlin’ Wolf record or some rockabilly record, he’ll know exactly what I’m talking about.

In the past, other members were good players, but they just didn’t have the same foundation for communication, and maybe they weren’t as dangerous or as hoodlum as the rest of us. It didn’t feel like a gang. We used to keep meeting Chopper at car shows. He plays in another band called Mr. Badwrench, and they’d play at car shows. When we ran into him, he looked like he could just step onstage with our band. It’s cool.

What was different in the studio was when we did “Taboo,” Chopper played guitar, I told him to play it in the same type of mood as on “Harlem Nocturne” by the Viscounts. I can talk to him and he knows what I’m talking about, whereas someone who’s just a fan and a good player wouldn’t know what that means. So there’s just that common ground and it cuts through a lot. There are a lot of things you can’t explain to people. They either know it or they don’t, or they’re into it or they’re not. There can be quite a gap.

So we’ve finally got this lineup where we all seem to resonate to the same music, the same movies, and the same kind of things.

How does your approach to playing differ when you’re performing live and when you’re playing in the studio?

They’re totally different, but both very important – like sacred events. Live is instant, and there’s a visual impact. What may seem amazing when you were there might not come across sonically if you hear the recording later. It just doesn’t seem as exciting as it was at the time. One thing about playing live is that you can never be that loud in any other situation. It’s just a license to scream and you can be as loud as you want. You can’t normally be that loud when you’re rehearsing or recording. You would never get anywhere with it. So it’s kind of exhilarating to be in front of these loud amps, with the monitors pounding, where you can feel the subwoofers under your feet while you’re on the stage. It’s spontaneous and thrilling.

Records are so magical because it’s this little mechanical thing. It used to be vinyl and now it’s a CD, but it’s still amazing that this little thing reproduces a universe of sound. It’s cool figuring out how to get all the dynamics reduced down to this mechanical thing. It can take someone who’s been dead for 30 years and then make them alive again. With a record, it survives. So making one is a very sacred event.

What’s different is that there’s so much distraction when we’re playing live. But when we record, we remind each other to play things like it was the first time you’ve ever played it because the worst thing that can happen would be that you get on auto pilot and you aren’t putting all your thought and emotion into it, or really feeling it.

In what ways has your audience changed over the years?

Lately, there’s been a very small handful of party poopers at every gig. This mosh pit thing has come back. I thought it had gone for good, but it has come back. I’m assuming there’s a movie out or something that this new generation of people has seen, and they think it’s cool or something. These people don’t come to see any particular band, but the people who did aren’t watching the band because they’re afraid of getting their heads kicked in by the moshers.

I could live without that. They don’t realize that we’re not a punk band in that way. Yes, we’re Satanic and sexy, but we’re not a punk headbanging band.

What kind of music do you listen to for enjoyment?

I listen to a lot of old stuff, and some new stuff, too. We listen to our record collections, which is mainly just old stuff – early rockabilly and wicked instrumentals. I love Dexter Romweber, although he hasn’t recorded recently. I love Jack Nitzsche, and I love Hank Williams III. I also like Hawaiian music because it calms us down and it keeps me away from medications and drugs and stuff. I try to calm down with music when I can.

What advice would you give to another player on developing their own sound and style?

Just start picking up stuff by ear. I think that’s definitely how you get your own style. Don’t take lessons. I think you’ll be more original if you don’t take lessons. And trust your ears. I think you can develop your ear just from doing it. It’s intimidating at first, but the more you do it, the better you’ll be at it.

Poison Ivy in 2002 with her ’58 Gretsch 6120. Photo:Bob Woodrum

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Nov. ’03 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.