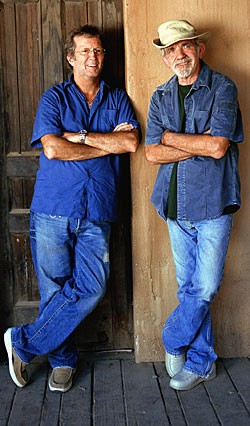

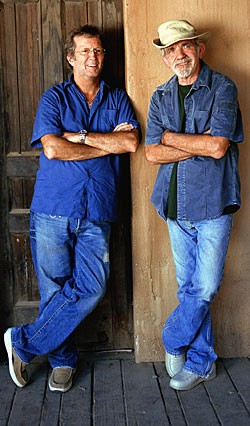

Photo: David McClister, courtesy Reprise Records.

Blowin’ Down the Road With Eric Clapton & J.J. Cale by Dan Forte

It’s fitting that The Road To Escondido, the long-awaited collaboration between Eric Clapton and J.J. Cale – a concept that seems, on the surface, to be so obvious, at least to fans – took decades to materialize

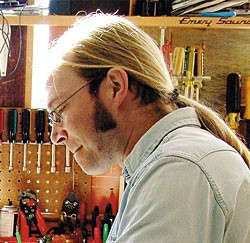

Cale, in particular, never seems to be in a hurry. Since his debut album, Naturally, in 1971, he has released – at a suitably laid-back pace – 13 studio albums (often recorded at his home; in some cases literally on his back porch) and one live album.

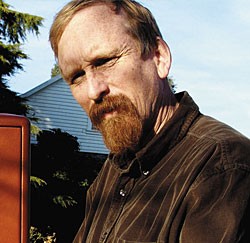

Clapton, on the other hand, in roughly the same span of time has released 16 studio albums, six live albums (including the Grammy-winning MTV session, Unplugged), and a collaborative effort with B.B. King, Ridin’ With The King. That’s in addition to the stints with the Yardbirds, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Cream, Blind Faith, and Delaney & Bonnie & Friends that preceded his self-titled solo debut, and the releases by Derek And The Dominos that followed it (one live, the other the classic Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs) – not to mention virtually nonstop touring (something Cale does rarely).

But despite only appearing onstage together twice (at shows 27 years apart), in a way they’ve been collaborating continuously since early 1970. That’s when, at the suggestion of producer Delaney Bramlett, Clapton covered “After Midnight,” an obscure single Cale had recorded for Liberty Records, and the pair’s lives became forever intertwined. A symbiotic relationship began, albeit long-distance.

Cale became as big an influence on Clapton’s songs (whether penned by J.J. or Eric himself) and overall sound as the blues masters had been on his guitar playing (which often veers into snaky, Cale-tinged licks). The man who virtually created the blueprint for the Guitar Hero, a huge influence on countless guitarists from unknowns to stars, is also part chameleon, capable of getting inside any number of other guitarists’ styles – including Cale’s.

And the Top 20 success of both the Eric Clapton album and the single of “After Midnight” provided Cale with enough income to launch a solo career and keep cranking out songs. Clapton subsequently cut “Cocaine” and “I’ll Make Love To You Anytime,” and other Cale tunes (like “Call Me The Breeze,” “Magnolia,” “Cajun Moon,” and his own hit single, “Crazy Mama”) were recorded by artists ranging from Chet Atkins to Deep Purple, from Waylon Jennings to one of Cale’s guitar heroes, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown.

Meanwhile, Clapton continued to assimilate and home in on the J.J. approach, with albums like 461 Ocean Boulevard and Slowhand (with the hit “Lay Down Sally,” penned by Clapton with bandmates Marcy Levy and George Terry) sounding like veritable homages to Cale.

In 1981, after Clapton released Another Ticket, featuring his original “I Can’t Stand It,” Cale laughed, “Yeah, I don’t get any reward for that – but that’s okay. See, he’s getting to a point where he can write that way. …You finally get to a point where you can write the whole thing in any style you want to do it in. So he finally figured out how to write all that. Which might be bad for me. But it’s not in the song; it’s in the feel. And once you’ve figured that out – well, he’s figured that out, so he doesn’t need to use my words anymore.” (Clapton later covered Cale’s “Travelin’ Light,” on Reptile.)

Although they’re obviously kindred spirits and, as Clapton says here, share the same philosophy, the two couldn’t have taken more different paths and led more different lives.

John Cale, who just turned 68, grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. By his teens, he and his guitar were playing country gigs before making the transition to early rock and roll. Along with other Tulsa musicians, including Leon Russell and Clapton’s future bassist, the late Carl Radle, Cale moved to Los Angeles in the mid 1960s. When he was booked to play off nights during Johnny Rivers’ long-running stint at the Whiskey A Go-Go, the club owner suggested he change his name to J.J. Cale, because there was already a John Cale, in the Velvet Underground. To this day, friends call him John or Cale, and he sometimes refers to “this J.J. Cale deal” as if it were a different person.

While Cale struggled as a session guitarist, engineer, and sometimes producer – or all three, as on an album by a nonexistent psychedelic band called the Leathercoated Minds – Eric Clapton was rising to heights no mere “guitar player” had ever scaled. The art-college student from the wrong side of the tracks first made his mark with the Yardbirds. He joined the band at age 18, and by the time he left a year and a half later his playing had reached a level of maturity well beyond his 19 years, soon revolutionizing blues and rock guitar.

After a month of intense woodshedding, he joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, where his massive tone, aggressive phrasing, and unheard of sustain on the instrument earned him a cult following eclipsing his bandleader. During the 15 months he was in the band, “Clapton Is God” graffiti began showing up at overpasses and tube stations.

Within days of his last gig with Mayall, he played his first gig with bassist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker, under the name Cream. Although it boasted fine songwriting and singing, the trio of virtuoso soloists was the band’s main attraction – much like that of a modern jazz combo, perhaps for the first time in rock history.

By the time Cream played its farewell gig in November of ’68, Eric Clapton had come to epitomize what every guitarslinger aspired to be: arguably the most famous guitarist in the world – at the ripe old age of 23.

But every accolade seemed to be counterbalanced by tragedy – all of which was played out in the fishbowl of success. Ironically, although he was wary of fame and fortune and the intrusion that comes with being a public figure, he invariably laid himself bare, expressing even the most personal and tragic events in song. His affair and breakup with his friend George Harrison’s wife, Pattie Boyd, inspired “Layla.” The song succeeded in winning her back (eventually resulting in his first marriage years later), but not before he became addicted to heroin.

Guitar-playing friends Jimi Hendrix and Duane Allman died young, and he later lost his close friend from The Band, Richard Manuel, and his longtime bassist, Carl Radle. And in August on 1990, after Clapton topped a bill that included fellow blues greats Robert Cray and Stevie Ray Vaughan & Double Trouble (with Buddy Guy and Jimmie Vaughan sitting in), the helicopter carrying Stevie Ray crashed, killing the guitarist, the chopper pilot, and Eric’s booking agent, bodyguard, and assistant tour manager.

The following March, his son, Conor, fell from a New York apartment window and died at age four and a half. In his honor, Clapton wrote the Grammy-winning “Tears In Heaven” – its gut-string fingerpicking and soft melody in sharp contrast to the blazing blues of years before.

Likewise, the pride and joy of The Road to Escondido‘s (Reprise) “Three Little Girls” is a far cry from the desperation of “Layla” – mirroring happier times for the 61-year-old husband and father of three young daughters. And having long since kicked drugs and alcohol, he founded the Crossroads Centre rehab on the Caribbean island of Antigua, in 1998 – largely underwritten by auctioning off guitars from his personal collection, in 1999 and again in 2004, coinciding with the Crossroads Guitar Festival, a two-day event held in Dallas.

If you want a barometer for Clapton’s enduring popularity, you need look no farther than the two most prized guitars that were auctioned that year. For a battered mongrel Fender Stratocaster (the famous “Blackie”) and E.C.’s red ’64 Gibson ES-335, Guitar Center paid nearly two million dollars – $959,500 for Blackie, $847,500 for the 335 (both since replicated in limited-edition reissues by Guitar Center in conjunction with Gibson and Fender).

Along the way, Clapton joined Bruce and Baker for a 2005 reunion of Cream at Royal Albert Hall, the site of the magnificent Concert For George, which Eric directed in memory of “the quiet Beatle.”

While Clapton’s every move was being scrutinized by both music and non-music press, J.J. Cale was opting for a comfortable life as a songwriter, even though he viewed himself as John Cale, guitar player. For years he referred to his albums as song demos, in which he experimented with various studio tricks and gadgets and tried his best to bury his vocals in often purposely murky mixes.

But all the while he was carving out a niche as a singer and songwriter as distinctive as his guitar playing – and as influential, infiltrating not just Clapton but Dire Straits and others. The laid-back mix of blues, country, jazz, and rock that came to be known as “the Tulsa sound” was largely forged by Cale. And Clapton filled his band with Tulsa boys, getting a steady diet of “Cale stories” years before he met the man – or, as he points out here, even saw a picture of him (oddly similar to Clapton’s biggest hero, Robert Johnson).

And the self-described “senior citizen” suddenly seemed more active than ever – releasing a live CD in 2001, playing the Crossroads Fest (with a certain Englishman on second guitar), and making his best album since Naturally and even submitting to on-camera interviews for an on-the-road DVD (both titled To Tulsa And Back).

In one of the interview segments in the DVD, Clapton talks about asking Cale to produce his next CD, wanting to capture that Cale sound and vibe. That project evolved into a duo album, co-produced by the pair.

With Cale writing 11 of the CD’s 14 cuts, and Cale’s Oklahoma “cronies” acting as the initial studio band, it’s not surprising that The Road To Escondido (on Reprise) sounds a lot more like a Cale record than a Clapton album – or more like the albums Clapton was making 25 to 30 years ago. Cale details, “Two of the songs were outtakes that didn’t make it onto earlier albums. I took the songs and rearranged them – said, ‘I think I’ll slow this one down,’ or, ‘Maybe I’ll use the words and the chord changes.’ ‘Who Am I Telling You’ was a boogie, and I turned it into a ballad. Seven songs I wrote for this CD, and ‘Don’t Cry Sister’ and ‘Any Way The Wind Blows’ I already did on older albums, but Eric wanted to do them. I sent him about nine of my songs and ten by other writers, and he didn’t record anything but my songs.”

The album eases into a mid-tempo groove on the opening “Danger,” showcasing the late Billy Preston on organ. “Billy played organ on almost all the cuts,” John says, “and Walt Richmond played acoustic piano on almost everything.” Clapton takes the first and third solos, with Cale in between. Even though Cale has influenced Clapton greatly, it’s still easy to spot who’s playing guitar – their styles are plenty distinctive. (On “Any Way The Wind Blows,” it’s the reverse – with Cale’s two turns bookending Clapton, before both go at it as the song fades.)

Cale employed three drummers – Jimmy Karstein, James Cruce, and David Teegarden – but, as he points out, “only one drummer would be playing a kit; the other two would be on percussion.”

Another Tulsa vet, Gary Gilmore, played bass, but, John explains, “He works as a semi driver, and he could only get two weeks off, so he had to leave to go back to his regular job. So Willie Weeks came in and played bass for one day, and Steve Jordan played drums just that one day, too. They’re both in Eric’s band, and Nathan East, who used to be in his band, was there one day, too. Later, Pino Paladino and (drummer) Abraham Laboriel, Jr., were overdubbed.”

“Missing Person” features a distorted solo by Eric, a slide solo by Derek Trucks, and some harmonized riffs by Cale. Trucks also supplied slide on “It’s Easy,” “When The War Is Over,” and “Who Am I Telling You?” For the bluegrassy speedster “Dead End Road,” there was only one man for the job: Clapton’s second guitarist in the ’80s, Albert Lee.

The only non-original is Brownie McGhee’s “Sporting Life Blues,” which features Taj Mahal on harmonica and Clapton playing an old guitar but a new acquisition – a 1929 Gibson L-5 that Cale gifted him during the sessions.

Acoustic rhythm was provided by Mrs. Cale, better known as Christine Lakeland, with Doyle Bramhall contributing rhythms and counter-melodies throughout, and John Mayer trading solos with Clapton on “Hard To Thrill,” which they co-wrote.

“Don’t Cry Sister” has all of Cale’s trademark licks, including harmonized, overdubbed, multiple guitar lines – all supplied by Clapton, who uncannily dupes every nuance from J.J.’s original version of the song, on the 5 album. Conversely, Cale, who mixed the CD, added some effects to Clapton’s already-wah’ed licks on “Ride The River.”

Before leaving for Japan, Clapton used his short break from the road to sit down for two days’ worth of interviews, and managed to get Cale to join him. Most of the time was devoted to TV and mainstream press, but the two guitarists generously set aside time for Vintage Guitar. They seemed relieved to not have to answer, “What’s the real meaning of the song ‘Cocaine’?” one more time, and talk music instead.

An interview with either is a rare opportunity; having both legends in the same room together was a once-in-a-lifetime master class.

Vintage Guitar: Why did it take so long for this to happen?

Cale: Eric came up with this idea, and it was time to do it. I think any other time before now, you know… making music is a creative process.

Clapton: It was so simple, it’s amazing.

Cale: It never dawned on me. People think that Eric and I are old cronies from way back, which we haven’t been. We’re kind of musical brothers – a long-distance kind of a thing. I don’t know how that would have happened any sooner; I guess I could have. It’s almost like asking, “Why weren’t you born in 1920? Why were you born in 1938?” I didn’t have anything to do with it. Eric came up with this idea, and I thought about it. I thought we’d probably play some gigs together.

Clapton: I wish we had sooner – for sure. I would hear those albums, in the ’70s and ’80s, and think, “Why didn’t he ask me to play on that?” [laughs] All these people he’s got. I’d think, “Maybe I’m too famous.” Because all the people who would be on John’s albums have been great players, but who are these people? Bill Boatman. Who’s Bill Boatman? All these great names; you’re just amazed.

And I certainly had to grow up, and I had lots of other fish to fry, too. But I would look at those records, and I would have loved to have played on “Magnolia” and those songs. So I just had to bide my time.

Do you think that because you just sort of organically let it happen when it was time, the age you guys are and this stage of your life, it made it a better record because of that?

Cale: I don’t think it made it any better… it’s what we did. Like I said, it just happened. We’re old enough to know as things happen in life, they just happen.

Clapton: I think it happened also because I didn’t want it not to. I mean, he might have asked me – who knows? But I asked him because I don’t want either one of us to drop off the planet without having this happen.

You might not have tomorrow…

Clapton: Yeah.

Cale: Billy Preston was on this. I did an interview today, and the guy knew I mixed the album, so he said, “The song ‘Danger,’ did you mix Billy Preston up because he died?” I said, “No, I spent several months mixing that, and I mixed that song before he died.”

Clapton: He thought it was like in tribute to him?

Cale: When I played it for Eric the first time, he said, “Oh, I didn’t realize Billy played so well on that one.”

Clapton: Yeah! It became actually the tone of the track.

Cale: So I mixed him up when I heard what he was playing. But he asked me did I mix the damn thing up because Billy had died. I went, “No, man.”

Clapton: Silly thing to say. He’s lucky you didn’t bite his head off.

When you got up and played the whole set with John at Crossroads, that was the second time you’d ever played together live. When was the previous time?

Clapton: Way back – in the ’70s, when we first met, and John came to play in London. I went to see him, and I can’t remember… I was with someone. Would I have been with Carl Dean (Radle)?

Cale: You might have been, because we came over to the studio after the gig.

Clapton: Olympic. Around Slowhand (recorded in May ’77). And Carl was in that band I had then, with Jamie (Oldaker).

Cale: He was way in the background; I didn’t even know he was back there. People told me, “Eric Clapton’s sitting in with you back there.” During his shy period.

Clapton: I thought it was the mode – that we had to work around him.

Cale: Eric was sitting back there, and some of the English people were mad at him because he didn’t stand up.

Clapton: That was the first time we met, and then a couple of times after that. Not many times.

The nice thing about the Crossroads set was that you just became part of the band. It wasn’t, “And now for the encore…”

Cale: Yeah, he’s great at that.

Clapton: Just try to get on the merry-go-round and figure out what they’re doing. What else could you do? I don’t remember how we decided it. Did we talk about that and then do it?

Cale: It was just, “Come on out and play.” I said, “I’m probably gonna do ‘After Midnight’ and ‘Cocaine’ and ‘Call Me The Breeze,’ and I don’t know what key I’m gonna do them in. Just follow it.” In the DVD thing (To Tulsa And Back), he said the song was half over before he figured out I was doing “After Midnight.” I change it up every night. I’m sure you do that, too.

Clapton: With my outfit, I keep everything pretty much the same except what you play in the solos.

Cale: I don’t. I change it. Sometimes I do it slow, sometimes fast. I’ve done “After Midnight” as a waltz before. I just get bored of listening to the same old thing. But I didn’t call out the key or nothing; I just started playing. I used to have the drummer count things off, but I had just gone out solo, so, even after I added some band guys, I just kept doing the solo deal, and they would join in. When I start off, it can be any song.

On that DVD, you’re talking about Cale, and you say, “If you played his music for a black person, they’d identify with it.” But the same thing could be said for your music.

Clapton: Yeah, hopefully. I don’t remember saying that, but I’m sure I did. I guess the point of it was that his thing seems to come from so many different influences. And I thank God that I got to know these guys, because I would hear stories about John – especially from Carl, because he was deep into all that. I went and stayed with Carl in his place out in Claremore, just outside of Tulsa, and we’d go into Tulsa almost every night and look at what was going on, and I was stunned by the amount of music that took place there, the amount of activity. I kind of got to see how this stuff came about.

Because there’s a lot of mythology – “Shootout On The Plantation” by Leon Russell and all this stuff. Leon sings about it, and Taj, and Jimmy Markham – all these famous people, who are only famous in this kind of network. People like (drummer) Chuck Blackwell. I find it incredibly appealing. So what I may have been trying to say was that that seemed to be a melting pot. I went to see the Gap Band play there, and it was not like a black club; it was just Tulsa people. It wasn’t about black or white or anything. I hadn’t been exposed to a lot of country where I came from. I got it all then; got a taste for it then.

Cale: Austin’s kind of that way. There’s a music scene there in and of itself. Tulsa was like that. I thought every place was like that. I thought if you lived in Cleveland, there was a Cleveland sound – and there probably is. It just didn’t resonate into another thing. I mean, look at Memphis; there’s a history there. The Tulsa people didn’t really make it into the big time. Some, like Bob Wills, did. Then Leon, David Gates. Eric’s a leader with a sideman philosophy, so all those people he liked, like Carl Radle, were sidemen.

Clapton: Yeah.

Cale: It’s easy to fit in when there’s no leader. That’s kind of what Tulsa is like; there’s not a leader. Somebody’s got to call the tunes, and somebody’s got to warble it out, but there’s no, “I’m the boss, and you’ve got to play it this way.” I think Eric was looking for that, because he’s even that way now – not being the guy way out front. I like being the guy out front, but I want some other people out front, too. Because you can really separate yourself mentally from the sidemen – you’re so out front, and there’s no way you can get around that. Tulsa was the kind of place you could slide in, and, “You want to be the leader? You be the leader tonight, you be the leader tomorrow night.” [Clapton laughs.] That was the Tulsa sound, to me. It was an attitude more than it was in music. There’s good music everywhere.

On the Tulsa DVD, you talk about playing more economically with Cale than you do in your own band. But then a year after Crossroads was the Cream reunion, where you had a lot on your shoulders – more so than even in your own band. Was that much of a hurdle?

Clapton: It’s very naked playing in a trio, but, then again, that might be a false assumption. It’s kind of like saying, “Well, there’s got to be something going on all the time.” There’s a level of anxiety in that. But maybe there doesn’t have to be. There are people who can put that kind of thing together and leave air. I just have that anxiety thing, where there’s got to be something going on. If there’s a space, fill it. It’s not right, but I’m compelled to do that.

But it worked with Cream, then and now.

Clapton: Well, it does work – and, if I don’t do it, Jack will do it, or Ginger. The first thing we did in England was good, because we worked on it. We spent time and gave it respect, and we spent a month rehearsing the songs and getting ourselves back up to speed. Then when we went to America, we made some arrogant assumptions that we didn’t need to do that again, and I think it suffered. It kind of got back to where it used to be; there was a bit on infighting and stuff. We went for the money, is what happened. We got a big salary for coming to America, and I think that bent everyone out of shape to some extent. That’s my take on it anyway.

The first time it was like a homecoming. It was a very emotional, genuine experience; it wasn’t for the money, and we all really got a lot out of it. Then someone started waving the dollar bills, and, “Ooh, yeah.” I could have said no, but I knew, for instance, Ginger has been struggling, you know, and he’s always been in trouble with the tax man and different things. He really needed that, so it was great to do it, in the end. He benefited greatly from that. And it was all right. But playing in a trio is hard work. If I were going to do it again, I’d learn how to play in a way that wasn’t so manic. There must be better ways to do the trio thing.

It’s funny, though, because there are people who base the way they play guitar, or took up guitar, because of that.

Clapton: I know, I know. Well, a lot of people reckon that Led Zeppelin came out of that. I mean, I was never a fan of Led Zeppelin, but the void that Cream left was like, “Oh, we need a super-group, heavy band.” And apparently they didn’t even know one another. It was a masterminded thing.

Did you use any guitars out of the ordinary for this CD?

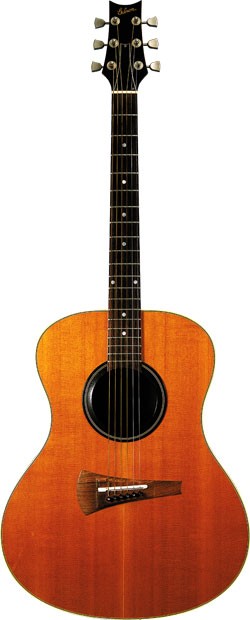

Clapton: John gave me a guitar. He had some guitars in the garage, and we started going through the cases, and I saw this one…

Cale: …a 1929 Gibson L-5 with a DeArmond pickup.

Clapton: And it’s fantastic! I used it on the album, because it had the sound. Just a little bit distorted.

Cale: He played that on “Sporting Life.” I originally bought it from Norm Harris. I’ve had it a long time, and I don’t ever play it. Eric came to my house without a guitar, and it was all funky. I said, “I’ve never cleaned it.”

Clapton: I started playing it, and I thought, “That’s funny; the paint’s coming off.” And it was dirt [laughs]!

Cale: There was some grease on it. It was not me. When I bought it, it was like that. It was in the original case, and when you open it, here’s this smell. Only something from the ’20s has that smell. And you let it sit out for 10 days and put it back in there – when you open it up again, it still has that. You could smell the guitar.

Clapton: That came home with me. He let me have that.

Cale: He played a Stratocaster on a lot of the CD, his signature model Martin on a couple of things, like “Three Little Girls.” And I don’t know if we used it or not, but you played a 335 on one thing.

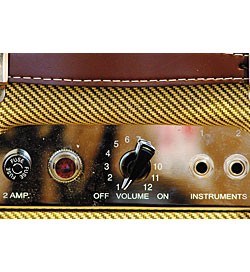

Clapton: Most of it, I played Strat and an L-5. (Ed. Note: Eric’s longtime guitar tech, Lee Dickson, reports that he mainly used his Fender Eric Clapton Signature Model Strats. Lee adds, “He also used a blond ’50s L-5 with alnicos. The 335 that was auctioned was a ’64; the one he’s playing at the moment is a dot-neck 1960. It’s one of the best 335s I’ve ever seen or played; it’s incredible.” In the studio, Clapton played through a ’57 reissue Twin with two 12s, “and we hired in a Champ and a Deluxe.” Dickson details: “Onstage, during this tour, he’s using the ’57 Twins, a Leslie, and he stopped using the Cry-Baby wah after the beginning of the tour.” Cale played a white Danelectro Convertible through a Fender Blues Junior as his main rig, and, he explains, “All the overdubs I did were mainly with my Casio Strat copy. The Dan-o has been modified; it has a piezo in it, and I play it in stereo – but for the record I just played it mono.”)

After auctioning all those guitars, are you down to the bare essentials?

Clapton: In the auction there was an L-5, and I’ve got L-5s. I often have two of each. So I’ve still got some nice guitars that I can play. Not as many as I had.

Cale: One of the best things you’ve ever done in your whole career is that DVD – and the festival itself. I’m talking about guitar players – and there are a lot of them in the world. What you did with that is you got all these wonderful guitar players and put all that together. You’re the only person on the planet who could have pulled that off.

I was there, and that was probably the best thing he’s ever done. And not only that, he played with everybody.

Clapton: You can’t make any money from doing events like that; the overheads are phenomenal. But the auction made $5 million, which goes straight into the rehab and sits there and gets drawn out when someone comes in who hasn’t got the money. So it will get used really well. What we’ll probably have to do is another mini auction, but I’m running out. Now I’m going to have to start to sell the stuff that I don’t want to sell.

But you could still buy more guitars.

Clapton: Well, I did. Right after that auction, when I sold the red ES-335, I went and bought a sunburst one. It’s a great guitar. I mean, the Fenders are fine, because the brand-new Fenders they make are fine; I love them. But I played this 335 the other night, and it’s so loud. I’d forgotten how loud they were.

Cale: Christine ordered one of your signature Stratocasters. What it’s got is the tone-tweaker deal.

Clapton: Fattens it out.

Cale: Runs up the midrange (25 db).

You’re an identifiable stylist, but sometimes you’ve been a bit of a chameleon.

Clapton: Yeah.

But, even when you are a chameleon, you’re still identifiable as Eric Clapton.

Clapton: I like to think so, yeah.

On the other hand, John, you’re more like, say, Lonnie Mack. Obviously, there was a lot of history that people didn’t know about, but the first record you ever made, it was as though your style sprang up full-blown, completely realized, and never really changed.

Cale: Yeah, I don’t know how to do it any other way. I tried. My critics go, “Well, everything you do sounds the same,” and I think, “Well, I need to invent something different from what I do.” So I tried, and it always sounded like crap. So I just keep doing the same thing.

But it’s not all the same. You put yourself in different environments, but whatever you do to your guitar sound or style, the approach is still J.J. Cale. And sometimes Eric plays like J.J. Cale.

Cale: Mainly on the songs I wrote.

You can spot who’s who on the CD…

Clapton: I think it’s fairly easy. I think we deliberately played our way. But I think maybe in the early years there was an over-riding mood to most of his records, but later things are really different.

Cale: Yeah, I don’t think I play like I used to. In fact, I’ve tried, and said, “I wish I could sound like that again.” But I can’t.

Clapton: For myself, if I can’t play the blues in something, I won’t go there. I’ll give you an example: I was approached to do a song on this Tony Bennett thing (Duets: An American Classic), and I said I’d love to. And they said, “Well, here’s what we suggest.” It was “Fly Me To the Moon” and “Just A Gigolo.” I can’t do t

What is most inspiring about collaborating with Ronnie?

What is most inspiring about collaborating with Ronnie?