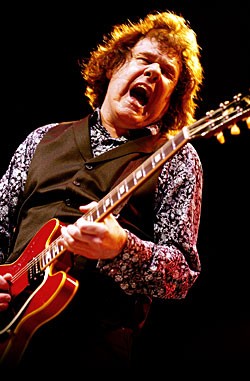

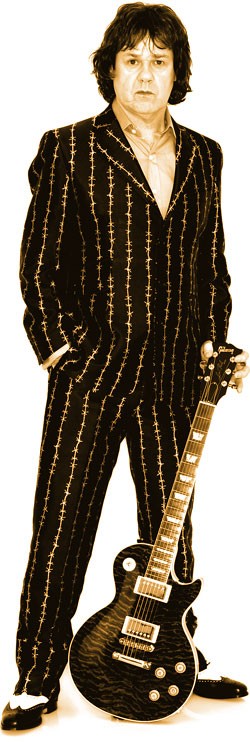

Taylor strums a flat-top with The Rolling Stones in early 1973. Photo copyright Marty Temme.

The mid/late 1960s were a fertile and progressive time for rock guitar, with “Swinging London” serving as the birthplace and incubator for the blues-rock idiom, in particular, as budding English musicians began discovering the sounds of everyone from Chicago blues artists such as Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters to the country blues of Robert Johnson and Skip James.

The mid/late 1960s were a fertile and progressive time for rock guitar, with “Swinging London” serving as the birthplace and incubator for the blues-rock idiom, in particular, as budding English musicians began discovering the sounds of everyone from Chicago blues artists such as Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters to the country blues of Robert Johnson and Skip James.

Striving to be heard in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, African-American blues pioneers were virtually ignored in their own country. But in a dismal post-WWII England where food was being rationed, these sounds became the stuff of dreams and escapism for kids who began picking up American blues records. In the U.S., the music was more for collectors and hip bohemians, but across the pond, Muddy, Wolf, et al, sparked a renaissance.

In early-’60s London that renaissance gave way to a cultural revolution that would be transferred back to the U.S., where the music became the template for a wellspring of creative guitar styles. It’s widely believed that the two earliest proponents of American blues in England (and responsible for striking up the British Blues boom) were Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies. Korner (a guitarist) and the harmonica-playing Davies served as historians of American blues and jazz, and became mentors to England’s emerging talent. The buzz began when the co-op group of Korner and Davies known as Blues Incorporated (formed circa 1961) began hosting a jam session at London’s Marquee Club. The sessions introduced figures who would later make major contributions, including bassist Jack Bruce and drummers Ginger Baker and Charlie Watts.

Through these sessions, Watts would be introduced to guitarist Keith Richards and vocalist Mick Jagger, and together would meet a young guitarist called Elmo Lewis, who perfectly emulated the slide guitar style of Elmore James. Lewis’ real name? Brian Jones.

In 1962, Cyril Davies departed Blues Incorporated to start the Cyril Davies All-Stars, whose ranks included (at various times) guitarist Jeff Beck and pianist Nicky Hopkins, who would go on to play sessions with the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Jefferson Airplane, and others. Via jam sessions, Korner became the spiritual catalyst for the formation of the Stones. He was also pivotal in the formation of the Blues Breakers, encouraging John Mayall’s decision to move to London and become a professional musician.

These bands began to make waves, their ranks containing guitarists with names like Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Peter Green, and Jimmy Page – players who used American blues as a point of departure but developed their own distinct voices. However, when discussing British guitar legends, one name tends to be left out…

Although only a few years younger than the aforementioned “deities,” Mick Taylor doesn’t receive nearly the accolades. Known mostly for being the guy who replaced Brian Jones in the Rolling Stones, as a teenager Taylor was reinventing modern blues guitar and how it could sound – and in the process developing one of the most stylistically unique guitar voices to come out of England. And today, his playing is as vital, lyrical, and emotive as it was 40 years ago.

Michael Kevin Taylor was born on January 17, 1949 and raised in Hertfordshire, north of London. He became interested in music at a very early age and after attending a Bill Haley and the Comets gig as a nine-year-old he began playing guitar. He began playing professionally a few years later and his first recording session came in August of 1964 while playing with a group called The Juniors. The Juniors cut just one single, “There’s A Pretty Girl,” but it was with local outfit called the Gods that Taylor began to become recognized (various incarnations of the Gods included future Ozzy Osbourne drummer Lee Kerslake and bassist/guitarist Greg Lake; the band would evolve into Uriah Heep).

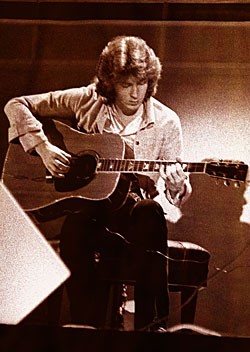

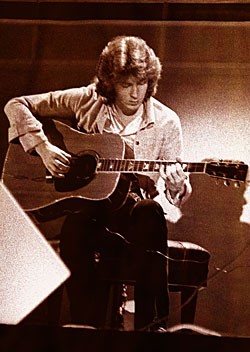

The opportunity to play with a truly prestigious and well-known outfit would come for Taylor in ’67, when the 18-year-old answered an ad placed seeking a guitarist. The band was John Mayall’s Blues Breakers, who were looking for a replacement for Peter Green. Taylor had made an impression on Mayall when he stood in for Eric Clapton at a gig in April ’66. He spent two years in the Blues Breakers, appearing on the albums Crusade, Bare Wires, and Blues From Laurel Canyon. His playing in this period was marked with exuberance and virility; his lines demand attention with their intelligence, sophistication, and emotional power.

On Crusade tracks such as Albert King’s “Oh Pretty Woman” and Freddie King’s “Driving Sideways,” it’s apparent that Taylor’s style, even in its formative stages, is quite different than those of Clapton and Green. He displays an affinity for the styles of Albert and B.B. King, in particular, but there’s also a very linear, lyrically melodic approach that gives Taylor’s musical personality a distinct identity.

During the recording, Taylor (like Clapton and Green before him) used a late-’50s Gibson Les Paul Standard plugged into a 50-watt Marshall half-stack. His economical single-line approach, melodic invention, and gifted bottleneck style brought a dimension that had been lacking in the band’s style – and Mayall was happy to make use of it. The Mayall/Taylor penned “Snowy Wood” is an instrumental-guitar showcase – and the perfect place to hear Taylor’s style in its formative stages.

Mayall’s concept for his group’s sound began to expand from the strict Chicago style he favored. Though there are horns on Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton, now Mayall was using their voices to incorporate a jazzier feel and sound – and Taylor’s style proved the perfect voice to implement and execute this new sound.

In late ’67, Mayall recorded gigs in Holland and Ireland, as well as Newcastle and Southampton. Released in two volumes, Diary of a Band shows how rapidly Taylor was developing. The Blues Breakers had begun to make longer, extended improvisations a cornerstone of their live performances, and hearing Taylor stretch out on tracks like “The Train” shows his melodic sense truly starting to flourish. The masterpiece, however, is the 10:52 opus “Crying Shame,” where we hear other Taylorisms emerge, like his use of hammer-ons; Taylor thought outside the pentatonic-blues box.

The next Mayall release would be an even greater departure. Inspired by suites performed by American jazz groups, Mayall appropriated the compositional framework on Bare Wires, taking advantage of extended song structures to express feelings about his then-recent divorce. His desire to meld blues and jazz gave the Blues Breakers a more varied musical palette; horns and violin contributed to the tonal spectrum. Arguably, Bare Wires is Mayall’s strongest recording, compositionally speaking. Taylor comes out screaming with an outburst of feedback in the portion of the suite called “Start Walking,” an upbeat shuffling swinger. Taylor’s style has taken even more identity. His expansive vocabulary and far-reaching ideas help his bluesy improvisations fit very nicely alongside the jazzier contributions of the horns and violin. As on Crusade, Taylor is ebullient on “Hartley Quits,” a buoyant blues with Taylor wailing along, aided by the floating, rhythmic horn thrusts. There are few moments so joyous in the Blues Breakers oeuvre. “Killing Time” follows, with Taylor alternating bottleneck and single-line soloing,.

Taylor underwent a flurry of activity in the guitar-acquisition department between February ’67 and November of ’68. After having his Les Paul stolen, he bought one from Keith Richards. The guitar had a sunburst finish and had been fitted with a Bigsby. Taylor used the guitar in the latter stages of his stay with Mayall. He also used a Selmer Hawaiian guitar in the studio. In early ’68, during a U.S. tour, he acquired a white Fender Stratocaster with a rosewood fretboard, which he ran through a Vox wah pedal on “No Reply” (from Bare Wires).

Taylor played a session with Sunny Land Slim while recording Slim’s Got Nothing Goin’ On in Los Angeles. During his second U.S. tour with the Blues Breakers, in the autumn of ’68, Taylor added to his collection an early-’60s Gibson SG/Les Paul.

In November of ’68, Taylor made his final recording as a Blues Breaker. Blues From Laurel Canyon was another concept LP, influenced by Mayall’s travels to California, which he thereafter adopted as his home. The album opens with the rousing “Vacation,” which Taylor displaying trademarks heavy vibrato and hammer-ons, wrapped in a firestorm of feedback. “Walking On Sunset” is a good-time blues extolling the sights and sounds of the Sunset Strip.

By this time, Taylor’s reputation as a lead guitarist was spreading, presenting him with more recognition – and opportunities. In November of ’69, Clapton told Melody Maker, “I saw John Mayall in America, and we jammed… Mick Taylor is very good – frightening.” Further session work came in the form of accompanying pianist Champion Jack Dupree on a few tracks for Scooby Dooby Doo, as well as a single recorded by the Irish singer/songwriter Jonathan Kelly. “Make A Stranger Your Friend” featured Taylor along with a cast of thousands, most notably Beatles’ associate Klaus Voorman on bass and guitarist Albert Hammond.

In his notes to Blues From Laurel Canyon, Mayall writes that Taylor, “…really shows his brilliance… He has worked with me longer than any other guitarist I’ve had and I hope that we’ll continue as a team for a long time to come.” However, Mayall’s wish would not come to pass. In late May of ’69, Taylor handed in his resignation. In England’s Melody Maker, Taylor said, “John wasn’t an easy person to work with because he’s got such a strong musical personality, but it was very enjoyable… until the last six months when I began to get fed up. Then I’d get up onstage and just go through the motions.”

In the 1969 Mayall documentary The Turning Point, a fresh post-Blues Breakers Taylor sheds light on his leaving the band; “Playing the sort of music that John plays, it gives you a lot of opportunity to develop your own ideas; it gives you a lot of freedom within the blues framework, anyway. So it did do me a lot of good being with John… He was only difficult to work with when I started to veer off towards other things. I’d be getting interested in other things – I didn’t really want to play his music… He’s not a difficult person to get on with really, though a lot of people seem to think so.”

Taylor’s departure wasn’t a blow to Mayall and in fact, he had begun to grow weary of the guitar/bass/drum core that had typified the Blues Breakers instrumentation.

During Mayall’s reevaluation, major changes were taking place within the Rolling Stones, which had a difficult period thanks to drug busts that led to a period of inactivity, which in turn detracted from the band’s music. Their Satanic Majesties Request, released in December, 1967, is considered the Stones’ answer to the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper, and though it has its moments, Majesties comes off merely as a half-baked, out-of-place attempt at psychedelia. The Stones realized that a return to blues-rock was in order, and they snapped to it with their next single, the hard driving punky blues of “Jumping Jack Flash.” Released in early summer ’68, it left no doubt that the big, bad Rolling Stones were back.

The band had not played in America since ’67, but beyond that they had a problem with Brian Jones, who due to substance abuse had become unreliable while making Beggar’s Banquet – and when he did show was in no condition to contribute. By ’69 the band had ascended a creative crest as it worked on Let It Bleed. With a U.S. tour in the works, Jagger and Richards knew Jones was unable to carry on. Urban legend has it they wanted Eric Clapton to fill the slot, but the stars were not in alignment. So Jagger turned to Mayall for advice, and Mayall suggested Taylor, whose first session with the Stones took place May 31, 1969. Taylor described the circumstances that precipitated his transition from Blues Breaker to Rolling Stone in the Martin Weitz BBC documentary, Godfather Of British Blues. “It had been merely four years and then [Mayall] certainly felt like it was, not only a time for a change for him musically, but time for a change of personnel and also it was time for him to move to America… John called and told me the Stones were interested in trying me out as a guitar player. I thought for some session work, but apparently it turned out to be a bit more than that.”

The fruits of Taylor’s first session with the Stones are born in various places. He plays driving rhythm guitar on “Live With Me” and contributes tasty acoustic slide fills to “Country Honk,” both from Let It Bleed. “Jiving Sister Fannie” and a cover of Stevie Wonder’s “I Don’t Know Why (I Love You)” were on the controversial Metamorphosis LP released in ’75. “Fannie” contains great lead work by Taylor, and “I Don’t Know Why” is given a chill by his stinging slide. Various outtakes and unreleased tracks from Taylor’s initial Stones session have been circulated as bootlegs.

On July 3, 1969, the Stones received news that Jones had drowned in his swimming pool. They were scheduled to play a free concert two days later at Hyde Park and were going to cancel until drummer Charlie Watts said they should play as a tribute. The concert, filmed by Granada television, was broadcast as “The Stones In The Park” and serves as an interesting document of the “new” Stones, lurching (as opposed to majestically rising) phoenix-like from the ashes. Jagger asks the crowd to “be cool for a minute” so he can eulogize Brian via a reading of poet Percy Shelley’s “Adonais,” after which several hundred butterflies are released from stage. Taylor uses the SG/Les Paul for most of the concert, but is also shown using the Richards Les Paul to play slide on the gloriously raucous blues “I’m Yours and I’m Hers.” HiWatt amplifiers can be seen on the stage behind Taylor and Richards.

With Jones laid to rest and Taylor in place, the Stones started their U.S. tour November 7 in Fort Collins, Colorado. Aboard were filmmakers Albert and David Maysles, to capture the band onstage and backstage, in hotel rooms, and even in the famed Muscle Shoals studios. The plan was to play across the U.S. and finish the tour with a free concert December 6 in San Francisco. The setlist showcased numbers from the new album, some from Beggar’s Banquet, a couple of oldies but goodies, and a couple of Chuck Berry covers for good measure. The live Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out, recorded at New York’s Madison Square Garden November 27 and 28, is a nice memento of the live Stones circa ’69, but doesn’t capture the excitement or sheer ferocity of the band’s live sound on that tour.

For that, one need only view the subsequent film Gimme Shelter or listen to the myriad of bootlegs that cropped up in the tour’s wake. For all intents and purposes, Taylor made use of the SG/Les Paul for the tour, though photos also show him with a Gibson ES-345 (interestingly, in the film Richards can be seen playing a Les Paul that belonged to Taylor). Ampeg was the amp brand of choice for that tour and the 1972 tour (immortalized in the film Ladies and Gentlemen, The Rolling Stones).

To hear the Stones live in 1969 is to bear witness to a musical awakening. What the Jones-era Stones offered was a raw alternative of darkness and angst to the Beatles’ more meticulously produced message of unconditional love. The band had a palpable edginess, even for the mid ’60s. And though the Stones had long been a solid musical unit, there had never been any virtuosos in its ranks. Taylor changed all that and influenced the way the other Stones played, lending a new level of sophistication to its compositions. For the first time, the Stones had a true musical heavyweight in their midst.

Taylor spent five years with the Rolling Stones, playing on Sticky Fingers, Exile on Main Street, Goats Head Soup, and It’s Only Rock and Roll. His instrumental and compositional contributions make those albums unlike any other in the Stones discography, and many believe Taylor’s years with the band are its musical and artistic apex, as his playing imbued the music with power, beauty, and a sense of humanness.

Taylor’s final gig with the Stones happened at the end of the band’s European tour in October, 1973. They would record It’s Only Rock and Roll, and by late ’74 Taylor decided to leave the band. Various reasons have been cited, but one that Taylor has corroborated is the band’s inactivity at that point, along with his growing desire to do something different; he simply felt a need to move on. Regardless of downtime among Jagger and Richards, Taylor had participated in more sessions outside of the Stones, most notably on Reggae by jazz flutist Herbie Mann and I’ve Got My Own Album To Do by Faces guitarist Ron Wood, who would soon become Taylor’s replacement in the Rolling Stones. Also released in August ’74 was Billy Preston’s Live European Tour, recorded while Preston was opening for the Stones, when Taylor would go onstage with Preston’s band.

After playing blues-based rock for years, Taylor was eager for a challenge that would stimulate his vast musical vocabulary, vision, and technique. So when he got the offer to join a new band being formed by bassist Jack Bruce, he jumped at the chance. Although the group (with forward-thinking jazz keyboardist Carla Bley and appropriately dubbed The Jack Bruce Band) should have reached amazing musical heights, it never quite got off the ground. In ’75 they embarked on a European tour, then played the U.K. and on June 6 appeared on the BBC’s “The Old Grey Whistle Test.” Apart from bootleg recordings and a CD release of “Whistle Test,” the band broke up before they got around to making a proper studio recording. But its music was truly a departure, and indeed a challenge for Taylor; jazz-rock compositions containing sophisticated chord changes and exotic time signatures. The project have not have brought Bruce and Taylor the commercial success of their previous bands, but no one was going to say that either was resting on their laurels.

In early 1976, Taylor did a session for Nick Roeg, director of the film The Man Who Fell to Earth (starring David Bowie), who had commissioned “Papa” John Phillips to compose music for the film’s soundtrack. In his book Papa John: An Autobiography, Phillips writes, “To me, Mick didn’t just play guitar, he performed 12-bar ballet on guitar.” He goes on to say that Keith Richards showed up one night and after an icy greeting, the guitars came out. “Guitarists become different people with a Gibson or Fender in their hands,” Phillips said. Soon after the soundtrack was finished, Phillips began hanging out with Jagger, and upon hearing some of Phillips’ songs, Jagger encouraged him to record a solo album, which through Jagger’s mediating would be financed by Atlantic Records guru Ahmet Ertegun and released on the Stones’ label. The resulting sessions would feature Taylor, Richards, Jagger, and even Ron Wood contributing bass, among others. Unfortunately, all of the excitement and good intention poured into the recording proved for naught and, due to various circumstances, the album would remain unreleased until 2001, a few months after Phillips’ death. Pay Pack And Follow stands as a lost but very interesting document in the annals of Rolling Stones/Mick Taylor history.

In 1978, Taylor began recording his first solo album, playing piano and writing songs. He wanted to make a mostly instrumental record to showcase his playing in a variety of musical contexts. Released in May of ’79, Mick Taylor does that and more. He plays most of the instruments, including bass, piano, and synthesizer.

The record also features Taylor in a role he had not previously filled – that of lead vocalist. Although the vocals are pushed back in the mix, Taylor can carry a tune. “Broken Hands” is a rocker in a definite Stones mold, reminiscent of “Soul Survivor” from Exile, rhythmically speaking. But the two outstanding tracks are instrumentals. “Slow Blues” contains a bluesy chord change showing off Taylor’s jazzy side. And “Spanish/A Minor” has more jazz-guitar inflections with “modern” guitarisms at play, subtle use of the vibrato that might bring to mind Jeff Beck. Unfortunately, changing tastes in the industry made the LP a hard sell, and Taylor found himself in his recurring role as “guitar god for hire.”

An interesting reunion took place in 1982, however, as Mayall decided to tour with senior Blues Breakers from various incarnations, pairing the excellent Taylor-period drummer Colin Allen with the Clapton/Green-era bassist John McVie. The tour made its way to New Jersey on June 18, turning the Capitol Theater in Passaic into a veritable blues shrine as the Blues Breakers were joined by guests including Buddy Guy and Junior Wells, Etta James, and Albert King. The concert was filmed and exists on DVD as John Mayall and the Blues Breakers: Jammin’ With The Blues Greats (Hybrid).

In ’83, Taylor would receive a call to record with Bob Dylan for what would comprise arguably the greatest of all Dylan’s 1980s recordings, Infidels. Sharing the guitar duties with Dire Straits’ Mark Knopfler, Taylor’s earthy guitar lines override the slick production and enhance the bluesy core inherent in Dylan’s songs. In ’84, after another U.S. tour with the Blues Breakers, Taylor went on the road with Dylan in a band comprised of Blues Breaker pal Colin Allen (drums), ex-Faces keyboardist Ian McLagan, and bassist Gregg Sutton, later of Lone Justice.

The official album, Real Live, captured during the European tour, is a good indicator of what this band sounded like, but there are also various bootleg recordings and videos where Taylor can be seen playing either his trusty Les Paul Standard or a Fender Stratocaster through a Marshall half-stack. As Sutton wrote in his cheeky memoir Here’s Your Hat… What’s Your Hurry?, “At our best, we sounded like the Stones playing the best of Bob.”

Sutton, who had seen Taylor as both a Blues Breaker and later as a Stone, elaborated on his unique style, “In some ways, his playing has not changed that much at all… of course it has changed and grown over the years, but there’s also a sort of purity. That voice is still there.”

Sutton also offers insight on Taylor’s personality. “One night, at the Road House Saloon, in New York, there was this real Vegasy-looking guy running the jam session. He didn’t know who Mick was, but he knew Mick was a ‘name.’ So he says, ‘Let’s do “Red House,” I’ll take the first lead and what’s your name – Mike, Mick?, then you.’ And I know this is going to be interesting, because Mick is gentle as a lamb, but he’s also a competitive musician… competitive but good-natured. But this wasn’t good-natured. So this guy takes his solo in ‘Red House’ and says ‘Mick, you take it.’ So Mick takes a couple of verses and he plays this long note as if he was ending his solo, and as the guy steps back up to the mic, Mick starts ripping another beautiful lead. And he kept doing this; every time it was time for another verse, Mick would wait for him to step to the mic so he could go into another solo.”

Around this time – the mid 1980s – Taylor developed a musical association with fellow guitar virtuoso Arlen Roth (see page 46 of this issue). This friendship resulted in Taylor taping a lesson in blues and slide guitar playing for Roth’s “Hot Licks” instructional series. The video is an interesting analytical study of Taylor’s complete style, wherein he explains elements of his phrasing and technique. Later, he is joined by Roth to jam and discuss style and influences.

Rolling through the ’90s, Taylor continued doing session work and playing with a variety of people, including guitarist/singer/songwriter Carla Olson, who met Taylor after she stood in for him in Dylan’s video for the Infidels track “Sweetheart Like You.”

“[Taylor, Dylan, et al] were in L.A. rehearsing for their European tour and Mick and Gregg Sutton came out to one of my band’s gigs and saw us play,” she said. “Mick got in touch with my manager and said, ‘If you guys are recording, I’d like to play on something.’”

The plan was to do a record with Gene Clark from the Byrds, but when he became unavailable, she and Taylor decided to do a live recording at the Roxy in Los Angeles. Recorded in March, 1990, and released on CD as Too Hot For Snakes, the record boasts a nice selection of Taylor soloing over Olson originals and revisiting old Rolling Stones songs, and even Taylor’s Mayall evergreen, “Hartley Quits.” Taylor recorded more solo albums, including 1990’s live Stranger In This Town and Stone’s Throw, recorded in England in 2000.

In recent years, Taylor has spent more time in Europe, recording and playing at festivals with his own group and as a guest with others. He has established a musical relationship with Irish guitarist/songwriter Barry McCabe.

“They say you should never meet your heroes, so I’m always prepared [for the worst],” said McCabe. “But Mick was very warm and very friendly, very approachable. We had a great time rehearsing our set, and he sat around and talked about Mayall. Obviously, he has a lot of respect for him. He also talked about seeing Rory Gallagher in ’67 or so. The conversation just flowed.”

In spite of all of Mick Taylor’s accomplishments and the praise he still receives from a varied musical circle, the specter of the Rolling Stones still seems a dark spot for him. “I deliberately avoided [talking about his time with them] and I think he appreciated that,” McCabe notes. “At one stage he said something about it himself; basically that that period of life casts a long shadow. And I left it at that. If he wanted to talk about it, I’d let him. He shouldn’t disown it, because he is part of the legacy. But I can understand that he has done other things and is happy to talk about those things, as well as things like jazz and guitars.”

Taylor’s importance does not start or end with his time in the Rolling Stones. It’s just one building block in a career that has spanned 40 years, and his dedication and commitment to music, his art, and the craft of guitar playing are models every musician should look to and uphold.

Special thanks to Christopher Hjort for allowing me to include equipment info from Strange Brew: Eric Clapton & The British Blues Boom 1965-1970

(Jawbone Press). Also, thanks to Carla Olson, Barry McCabe and Gregg Sutton. Fore more, visit micktaylor.net.

This article originally appeared in VG

‘s April 2008 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar

magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.