-

Gil Hembree

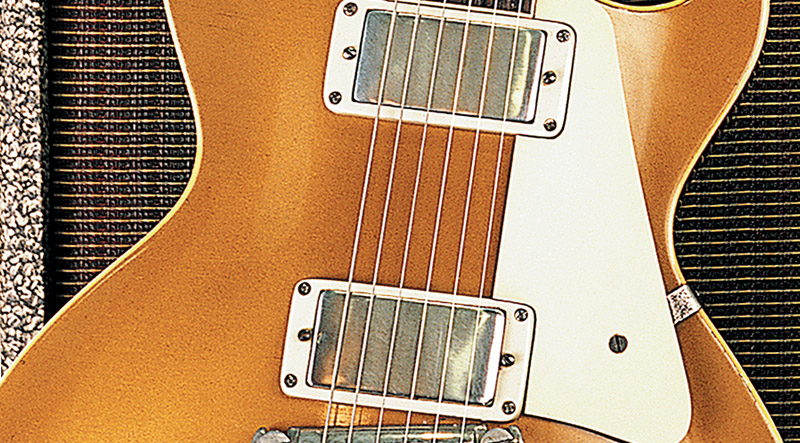

Gibson Humbucker

Crunchy, Clean Dirt

Gibson and Fender may be the longstanding heavyweight rivals of the electric guitar game, but they have one very important thing in common: they revolutionized the guitar industry. Fender took a monumental step with the introduction of the first commercially successful solidbody guitar in 1950. Gibson reacted by introducing the Gibson Les Paul Model solidbody.…

-

Gil Hembree

Gibson Kalamazoo Award

Designer's Dream Come True

In 1978, Gibson craftsman Wilbur Fuller produced the company’s first hand-carved, tuned-by-ear custom guitar. The instrument, which in a blind sound-off with some of the best instruments of its era, won the hearts of Gibson brass, ultimately became the Kalamazoo Award. Gruhn’s Guide to Vintage Guitars tells us that the Kalamazoo Award was a 17″…

-

Gil Hembree

Kenny Olson

The Detroit Fender Bender

If you’re talkin’ Detroit rock, vintage guitars, muscle cars, then you’re talkin’ Kenny Olson. VG met Olson at the Detroit Guitar Show, and it didn’t take long before he was talking about old Strats and Teles. That seemed natural for a Fender-endorsed lead guitar player, but for Olson it was more. He loves the old…

-

Gil Hembree

Gibson Collector’s Vault

Heavyweight bodyguard for your rock stars!

Can you truly put a price tag on peace of mind? For guitar collectors, the answer often is “No,” because like many other increasingly valuable collectibles, vintage guitars cannot be replaced. So it is that we record, photograph, catalog, and insure our collections so that if they’re stolen, we’ll have as much info as we…

-

Gil Hembree

Gibson Electric Uke

By Request of Arthur Godfrey

Ted McCarty, Gibson’s president from 1948 to ’66, was responsible for some of Gibson’s greatest designs. While McCarty cites the Les Paul Model as his most important design, his other credits include the ES-335, the Flying V, the McCarty pickup, and McCarty bridge. But one design that never appears on McCarty’s list of accomplishments is…

-

Gil Hembree

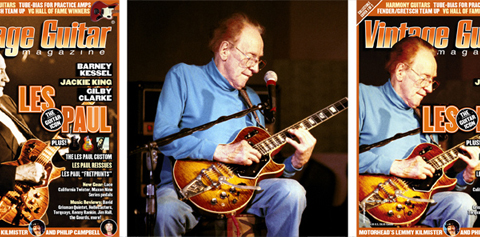

Les Paul

Birth of a Guitar Icon

Fifty years ago, Gibson’s new Les Paul Model was quickly becoming one of the company’s most popular guitars, and (though there was no way of knowing it at the time) was on its way to achieving mythical status in the realm of the electric solidbody. With the recent observation of the model’s golden anniversary, Vintage…