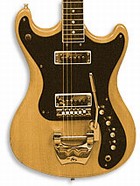

1966-67 Holman Classic, same body as the Wurlitzer Cougar.

Whether or not you think they’re from Oz probably depends on your tastes, but one thing’s for certain – they’re not in Kansas anymore. But once upon a time they were. Holman guitars, that is. Or shall we say Wurlitzer guitars, or Alray, or LaBaye, or 21st Century, or Mistic?

Actually, we are speaking of products that all emanated from the Holman-Woodell guitar factory located in Neodesha, Kansas, gracing the world stage from late 1965 to around 1968, at the height of that decade’s guitar boom.

Holman may not be a brand name that rolls off the top of one’s head when the subject of guitars in the Swinging ’60s comes up, but the Holman-Woodell factory did produce some pretty interesting artifacts and, with some deft archaeology – and a lot of help from our friends – we can at least bring a good bit of this long-buried story to light. While a fair number of questions remain to be answered about Holman guitars, we can relate enough of the history to give you a decent idea of these wonders from Kansas.

Southeast Kansas

Unless you’re an area native, the name Neodesha probably doesn’t light up your face with instant recognition, so let’s begin with a little geography. Assuming you know that Kansas sits almost smack dab in the middle of the lower 48, Neodesha is a tiny little burg nestled in the southeastern corner of the state. About the only recognizable landmarks within a 25-mile radius is another small town you may have heard of, Chanute, home of Bud Ross and Kustom amplifiers and guitars. In fact, speaking of Oz, Dorothy might very well have come from somewhere near these parts. Head 100 miles or so straight north on route 75 and you’re in Topeka. Add another 20 miles or so to the northeast and you hit Kansas City. Southeastern Kansas may seem an unlikely place for a couple of guitar factories, but there it is. The Chicago of the plains.

Howard Holman and Victor Woodell

Holman-Woodell, Inc., was founded in Neodesha, Kansas, in about May, 1965, by Howard E. Holman and Victor A. Woodell. Holman hailed from the little town of Independence, Kansas, a few miles to the west, where he ran a local music store, the Holman Music Company. Woodell was the money man, described as a former industrialist with experience in electronics manufacturing who had already retired to Sarasota, Florida. The new factory was located upstairs in the Fawcett Building at 515 Main Street in Neodesha.

The intent of the new Holman-Woodell concern was to manufacture “…items in the musical-electronics field as well as electromechanical and other electronic assembly work.” Two other key players were G. S. “Stan” White, a local with manufacturing experience who was responsible for setting up the factory and handling public relations, and Harold Wheeler, an engineer who’d worked with other electronic and manufacturing companies. One other management person mentioned in another newspaper account was Clement Hall, function unknown. Holman had plans for national distribution and hope to eventually employ up to 100 workers.

Holman and company were busy, and on November 24, 1965, Holman’s first guitars were debuted in a performance by local musicians at the Neodesha Lion’s Club. This first-ever Holman guitar gig featured Doyle Reading on lead guitar, backed by Randy Blumer on drums, Norman Blumer on rhythm guitar, and Larry Blumer on bass. All were from Independence, Kansas. Reading was the Holman-Woodell production supervisor and, based on evidence from interviews and his own testimony, probably the chief guitar designer at the company. During this debut, various Holman guitars were displayed and Stan White announced production to be at about 50 guitars a week. White and Reading fielded questions, and Holman also announced that national distribution would be handled by the Wurlitzer Music Company, the famous piano and organ manufacturer and instrument distributor.

Doyle Reading

According to Reading and others interviewed, he was primarily responsible for the design of the Holman/Wurlitzer guitars. Reading was, by some accounts, once a woodshop teacher in the local schools, so he had a good knowledge of the art of woodworking. He was also a pretty good guitar player, specializing in fingerstyle, in a Merle Travis sort of mode. Indeed, understanding Reading’s preference for fingerstyle in many ways explains the sound of Holman-made guitars, which have pretty good separation and clarity, but will never, ever push an amp into distortion. Of course, the Travis-picking country style was still especially influential in Middle America during those pre-psychedelic days of innocence.

A Kustom Konnection

If the name Doyle Reading sounds familiar, it’s because he later played a part in the production of Kustom Guitars, in Chanute. Reading left Holman in 1967 and hooked up with Kustom to make their guitars. Indeed, it was Reading who played a major role in the design of Kustom guitars.

While the subject of Kustom and Bud Ross has come up, let’s talk briefly about that connection. In conversations, Ross recalled having dreamed up a guitar design in around 1966 and approached the folks at Holman about it. He never heard back from them, but later he saw one that looked like his, carrying the Wurlitzer brand. In conversations with Reading and others, however, Reading generally receives credit for the design of both the Wurlitzers and the later Kustoms. Whether Reading and the folks at Holman were actually influenced by Ross’ early design or whether the whole thing was a coincidence will probably never be resolved, although given the timing of things, the latter is more likely to be the answer. Certainly, holding a Kustom and a Holman guitar one after the other would never make you think they had anything in common. In any case, Ross felt he’d been taken advantage of, and went on to work on a totally new design and, with ex-Holman production supervisor and guitar designer Reading, began making Kustom guitars in 1968. But that’s another story (which you can read about in Guitar Stories, Volume 1).

The ladies

In a Neodesha Register article on the industrial diversity of Neodesha, mention is made of the Holman-Woodell factory. By April of 1966, Holman occupied two floors of the Fawcett building and employed 17 full-time and three part-time employees, with Howard Holman as President and General Manager. What’s especially interesting is that the Holman-Woodell factory employed a fair number of women in its manufacturing process, probably a function of its non-urban location. In an August 7, 1966, Wichita Eagle and Beacon newspaper story on the plant, several ladies are shown assembling electronic harnesses. This would make Holman-Woodell particularly progressive for guitar companies, which were, at the time, still traditionally male domains.

Elkhart, Indiana

The Holman story sprang from a connection between Howard Holman and the Wurlitzer company of Elkhart, Indiana. Wurlitzer had been a major distributor of musical instruments since the late 19th century. Holman ran a music store, so he had an opportunity to make the right connections. According to Stan White, Holman got the idea of building guitars and set about trying to convince Wurlitzer to back the venture. After some reluctance, Wurlitzer finally agreed. In the Spring of ’66, Wurlitzer was identified as the exclusive distributor of Holman-made guitars, carrying the Wurlitzer brand name. Apparently, the earliest Holman/Wurlitzers were built above Howard Holman’s music store in Independence, prior to the relocation to larger facilities in Neodesha.

It’s not certain whether there were any early Holman products other than Wurlitzer guitars, but the new Wurlitzer line, illustrated in an undated flyer from ca. 1966, probably represents the initial output from the Holman-Woodell factory. Such a conclusion is confirmed by the examples of Holman guitars, which are very similar to Wurlitzer guitars.

Wurlitzer Wild Ones

A snapshot of the Wurlitzer guitars can be seen in an undated catalog entitled The Wild Ones: Stereo Electric Guitars by Wurlitzer, a copy of which was provided by Stan White, former Holman production chief. The copy read: “A brand-new series of quality Wurlitzer Guitars for the full-of-fun crowd! Unparalleled Versatility. Brilliant Response. Beautiful Appearance…Whether you’re playing jazz, rock, or folk music, you’ll praise the extremely fine playing qualities, the unusual flexibility and rich, vibrant tone…”

Three models were offered, the Cougar, the Wildcat and the Gemini. All were two-pickup offset double-cutaways with increasingly far-out styling. All had a six-in-line headstock that was somewhere between Jimmy Durante’s schnozzola and Gene Simmons’ tongue, actually one of the neater interpretations.

The Cougar was a slightly trimmer Fender-style offset double-cutaway. This had a large, white pickguard that covered both front horns, came down behind the bridge and ended in a long archipelago with two volumes, two tones and a jack. A fader control (for stereo effects) sat on the treble horn. A three-way toggle was located on the upper bass horn. Above each Sensi-Tone pickup was a rocker switch that let you pick rock or jazz tones, basically different capacitors. The Model 2510 came in Taffy White. The Model 2511 was Lollipop Red. The Model 2512 was sunburst.

The Wildcat was almost the same, except it had a more exaggerated offset cutaway body, with a larger upper extended horn and a more rounded lower horn, plus a much narrower waist than the Cougar. The effect is much more like an Alamo Fiesta. The Model 2520 was Taffy White, the 2521 Lollipop Red, the 2522 sunburst.

The Gemini was definitely the cool dude, with equal, very pointed double cutaways, with a pointed lower bout, plus a German carve around the edges, definitely George Jetson. The electronics were identical to the Cougar and Wildcat. The Model 2530 was Taffy White, the 2531 Lollipop Red, and the 2532 in Licorice Black.

Whether or not there was ever a Wurlitzer bass is unknown. We do know the Holman-Woodell factory produced some solidbody basses by ’67, so even though Wurlitzer did not promote them, don’t be surprised if you find a Wurlitzer-brand bass made in Kansas.

Holman features

The Wurlitzers all had characteristic features that distinguish Holman-Woodell products. Except at the end, which we’ll cover in due time, most Holman-made guitars were solidbody electrics. According to newspaper accounts at the time, they used a mix of locally-available material plus lumbers from Canada and Brazil, presumably Canadian maple and Brazilian rosewood for the fingerboards. These had maple bodies and bolt-on maple necks with rosewood ‘boards. Headstocks were mostly six-in-line, in a couple styles, usually with Kluson Deluxe tuners. The fingerboards were generally bound, with dots. A distinguishing feature is a common, if not exclusive, use of red dot position markers set into the binding. The necks are usually fairly thin – not as slim as contemporary Kapa or Hagstrom guitars – but quite comfortable.

The Sensi-Tone pickups used on Holman guitars were also quite unusual. They look a bit like DeArmonds, but they were actually made by Holman-Woodell at the Kansas factory. These were large P-90-size single-coils with a chrome top cover and adjustable exposed polepieces. The strange thing about them was that the neck was bolted in at a slight backward angle, requiring different heights. This was achieved by stacking different amounts of thin, white plastic shims or spacers, sort of like surrounds, under the chrome top of the pickup. No other manufacturer used such a technique.

Most Holman guitars, regardless of brand name, featured their version of a Bigsby vibrato, called the Wurlitzer Vibratron, with a W cutout in the base. These passed over plastic saddles in the Tunemaster adjustable bridge. The Wurlitzer guitars were wired for mono or stereo output, although other brands produced by the factory – possibly later ones – were simply regular mono. Necks were maple with truss rod adjustment.

Pulling the plug

It’s not known for sure how long Holman/Wurlitzer guitars lasted, but probably not long. The whole chronology of the period is sketchy at best, but with a little intelligent speculation, we can probably deduce what happened. It was Holman who made the contact with Wurlitzer, probably through his music business in Independence. This was the very period when large companies saw the potential in guitar manufacturing and wanted to get in on the action. Ironically, of course, the guitar boom of the ’60s was almost over, but no one saw the looming precipice yet in 1965. It was in ’65 that CBS bought Fender. Baldwin, spurned in its own bid to take over Fender, promptly purchased first Burns of London, then Gretsch. Seeburg, the big juke box company, purchased Kay. It probably didn’t take much to convince Wurlitzer to get into the game, too.

In any case, Holman talked Woodell into fronting the money to start a factory, and Wurlitzer agreed to take the guitars. The first Wurlitzers started rolling off the line in late 1965. These were probably produced through 1966, possibly into 1967, but certainly by ’67 the bloom had worn off for Wurlitzer. By 1967, Wurlitzer had switched suppliers to Italian-made Welson guitars, leaving Holman-Woodell in the lurch. It was in 1967, you’ll recall, that Reading knocked on Bud Ross’ door, having left Holman-Woodell, perhaps a victim of Wurlitzer’s departure.

The exact reason Wurlitzer abandoned Holman-Woodell is unknown, but if you’ve ever handled one with the finish peeling off, you probably have a good clue. While the guitars were not poorly made, they did have finish problems. Apparently quite a few units were returned with the finish flaking off, mainly due to inadequate priming. Guitars returned for refinishing will very quickly eat into your profits and dealer loyalty. Whatever the reason, Holman/Wurlitzers lasted only about a year, max.

Holman guitars

At some point, the Holman-Woodell folks began to sell their guitars carrying their own Holman brand name. It’s not known if these appeared concurrently with the Wurlitzer brand, but it’s more probable that Holman-brand guitars appeared in 1966 or later. A good guess might be that when Wurlitzer pulled the plug, Holman-Woodell was left with lots of stock, and decided to try to market guitars under its own name. After the Wurlitzer episode, Holman-Woodell ditched the idea of stereo-mono output, favoring more traditional mono output.

The Holman Classic shown on page 23 (SN 155226) has ’66 pot dates, though that, of course, only establishes an early date for the manufacture of the pot itself. If Wurlitzer left Holman-Woodell 55holding the bag, they may have had a large supply of pots that lasted a long time). This guitar is a blond natural-finish Strat-style double-cutaway solidbody with most of the typical Holman-Woodell features. It has a 243/4″ scale, string tree, six-in-line Kluson Deluxe individual covered tuners with chrome buttons, truss rod adjustment at body with covered access hole, black pickguard with gold-colored imprinted logo, two Sensi-Tone adjustable pole single-coil pickups with plastic and metal covers marked Channel A and Channel B, two volume and two tone controls (lead tone pot has two capacitors – .022 and .001 – yielding thin single-coil sound at 10 and fatter humbucker sound at 1, but which adds highs to the rhythm pickup when set at 10; go figure), three-way pickup selector, and Wurlitzer Vibratron Bigsby-style vibrato. Unlike its Wurlitzer brothers, this guitar had only mono output. Also, unlike the Kiss-Tongue heads seen in the Wurlitizer flyer, this has a sort of bizarro squarified Strat-style headstock shape. These are seen on other later Holman factory guitars.

The Wurlitzer Wildcat (page 25) was also produced bearing the Holman brand name. While we don’t have an example to show, so, too, undoubtedly, was the Gemini, since it survived into the Alray era.

The Holman brand continued to be made for some time. It’s not clear whether it was simply a transitional brand between Wurlitzer and Alray or whether it actually ran concurrently with the later Alray name. This may be an academic consideration because the entire factory history wasn’t really very long, anyway! The reason this issue is even raised is that as you can see from examples pictured here, at some point Holman-Woodell came up with a semi-solid guitar and bass design with models known as the Long Horn and Short Horn. While these appear in the Alray catalog, there are examples also bearing the Holman name, often engraved into the pickguard. Generally speaking, the Holman versions continued using the sort of bizarro Strat-style headstock, whereas Alrays tended to favor a wide three-and-three head. However, so much variation exists in the few examples known to us that firm conclusions are hard to draw. The unsolved mystery is: did the Holman folks design the semi-solids right after losing the Wurlitzer business? Or did Al and Ray, whom we’re about to meet, come up with the idea after taking over, and continue to make both Holman and Alray guitars (possibly using up necks with the Holman head)?

Down by the Bay

At some point, late in ’66 or early in 1967, the Holman-Woodell company was put in touch with Dan Helland, a young photographer, music teacher and would-be guitar designer living in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Dan worked for Henry Czachor, of Henry’s Music in Green Bay, and had this idea that an electric guitar is just a piece of wood with a neck, right? The wood could be anything, even a 2 X 4. Why not slap a neck on a 2 X 4 and have a guitar? The LaBaye 2 X 4 was born. Why the name LaBaye was chosen is unknown, but there are a lot of folks of French heritage in northeastern Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and Green Bay is, after all, situated on “the bay.”

The LaBaye 2 X 4 guitar was called, in quotes, the Six, while the bass was called – dare to guess? – the Four. Ta dum.

Basically, except for the novel body, the LaBaye 2 X 4 guitars and basses were similar to Holman-brand instruments, with Sensi-Tone pickups and mono output. Unlike Holmans and Wurlitzers, the LaBayes did not feature the jazz/rock rocker switches. Also, in a design nightmare, the 2 X 4s put the three-way toggle down on the bottom of the log, so that the slightest movement while playing it was likely to knock the pickup selector out of position. The Wurlitzer Vibraton vibrato was used, and the neck was pretty much standard Holman, though the headstock had a more narrow arrowhead profile. One cool thing, however, was the controls, which were round rollers set on top of the guitar and which – in a gesture that would be sure to please Nigel Tufnel of This Is Spinal Tap – go to 12! Given the crummy output of these pickups, that’s a real joke!

Though it wouldn’t much matter. Like so much else produced by Holman-Woodell, LaBaye 2 X 4s failed to excite much interest. Helland took some 45 prototypes to the Chicago NAMM show in ’67, where exactly none were sold, and no more were ever ordered from Holman. Basically there are only about 45 LaBaye-brand 2 X 4s. Apparently, the factory must have made more parts than were assembled and delivered, because a few were seen later, carrying the 21st Century brand name. Estimates are that there are fewer than 100 2 X 4s, regardless of brand name.

One-offs and protos

Both the inconsistencies among Holman and Alray guitars and weird tangents, such as LaBaye, bring up another confounding feature of the Holman saga. There are a great many, well, proportionally speaking, one-offs and prototypes. We know of at least one guitar made for Lucille Shukers, the wife of a Holman employee memorialized in a guitar inscribed with her name. Doyle Reading has a 12-string with a very unusual, pointed, six-and-six headstock. And, speaking of headstocks, Stan White sent along a photo of a one-off which placed a Playboy Bunny head atop a Holman Classic! Indeed, it is reported that Lucille Shukers actually posed for promotional photos with this guitar. The point is that just because you find something that doesn’t fit the standard catalog, that doesn’t mean it’s not original!

At this point we should also mention another weird Holman project that fared even less well than the guitar venture: the electronic washboard. Little is known of this device except that Roy Clark apparently liked the idea, but it quickly disappeared from the musical instrument horizon!

Enter Al and Ray

The next chapter of the Holman-Woodell story was about to unfold, starring two shadowy figures named Al and Ray. Alas, their surnames are lost to posterity, unless someone out there knows who they were (please get in touch with us at if you do).

According to some sources, Al and Ray were brought in by the management to whip things into shape after the exodus of Wurlitzer. Reportedly, the owners were unhappy with Howard Holman, and presumably around this time Holman left the picture. The date of this occurrence is also unknown, but we do know that the Holman-Woodell name lasted until the end of November, 1967. So, backing up from this, it’s a reasonable guess that Al and Ray took over in around the beginning of 1967, give or take.

During their tenure, Al and Ray changed the brand name to the combination of their first names: Alray. As mentioned previously, some Holman guitars were made bearing features characteristic of the Alray line; it’s not known if these features were designed before the change to Alray, or whether the new designs can be attributed to Al and Ray, and the Holman brand was used simultaneously. An Alray flyer introducing “A New Guitar Line,” which is our only evidence of their management, is undated but, based on our assumptions, is probably from 1967. The factory is still listed as being in Neodesha, but the sales offices were now at 524 North Broadway in Pittsburg, Kansas. Pittsburg is a little town 50 miles or so due east of Neodesha, right on the Missouri border. Presumably Al and Ray, the new owners, hailed from Pittsburg.

Based on the offerings shown in the flyer, they seemed to know something about guitars, because the Alray line was the most ambitious to come out of Neodesha during its brief existence. Some of the models were clearly derivatives of the early Wurlitzers – why trash the tooling? – but some were new, including the first and only acoustic guitar and including some semi-solidbodies which bring to mind the later guitars of Kustom!

Alray/Holman solidbodies

The ca. 1967 Alray line basically consisted of three solidbody electrics, four semi-solidbodies, and one acoustic. Electric models were available as six-string guitars, 12-string guitars and bass guitars. The electrics all continued to sport typical Holman post-Wurlitzer monaural electronics, with Holman Sensitone pickups and the old Wurlitzer Vibratron vibrato, except on the 12-strings and basses. No mention of finish options, but the photocopied flyer shows guitars in natural, sunburst and a solid color, probably red.

The solidbody electrics were basically the old Wurlitzer line but with the bizarro Holman headstock design. The Alray Classic was the old Wurlitzer Cougar, a conservative offset double-cutaway, Strat-shaped guitar. The Alray Traditional was the slightly more whimsical Wurlitzer Wildcat, with narrower waist and wider, Alamo-style cutaway horns. The Alray Sting Ray was the old Wurlitzer Gemini, with the groovy angular body styling.

Another Kustom connection?

No description of the construction of the semi-solid models is offered, however these have wide, center-pointed, three-and-three heads that sure look like Kustom’s. Also, the semi-hollow bodies have rounded edges, not hard edges as on a typical thinline guitar. The sound hole, on the lower bass bout, was a sort of chili-pepper-shaped affair set curiously inside a piece of papaya-shaped plastic pickguard material. Kustom guitars, you’ll recall from Guitar Stories Volume 1, were carved out of a front and back, which were glued together, and featured a cat’s-eye soundhole. Alray semi-solids sure look like they could be similarly constructed. With Kustom guitars soon to be made just up the road in Chanute, it’s tempting to suspect a connection…

The four Alray semi-solids included the Sting Ray, Bob Cat, Short Horn, and Long Horn. The Sting Ray was not illustrated, but presumably was based on the solidbody design. The Bob Cat was the same body style as the Alray Classic (Wurlitzer Cougar). While almost all Alray guitars came with two pickups, the Bob Cat guitar and bass were also offered with a single-pickup option. The Short Horn had a wider body than the other Alray guitars with two equal cutaway horns, the upper slightly thicker than the lower. As suggested, the horns were short only in comparison to the new Long Horn, which was virtually the same except the horns were more pointed and extended forward a bit more. There’s something slightly Rickenbacker-ish to these (as there is with Kustom guitars), and, indeed, the controls sat down on a little football-shaped plate that looks vaguely Rick-ish.

The acoustic

The Alray Acoustic Guitar was a large, almost dreadnought-shaped affair with somewhat awkward upper shoulders squared off, almost like a Harmony Sovereign. The copy states that this was a handmade instrument, with the finest woods “…worked and matched by hand.” A fancy rosette surrounded the soundhole, and a large, goofy mustache bridge centered on the belly, looking very country/western. It’s not known if the neck was glued in or bolted on, but it had the wide three-and-three shape of the semi-solids.

At least one other model, presumably an Alray, has been seen, another more traditional semi-hollowbody (or perhaps even hollowbody). This is shown here in a 12-string version with a red ES-335-style body with twin f-holes and the Alray-style six-and-six flared pointed headstock. This had a clear plastic pickguard. Electronics were otherwise typical of Alray guitars. It is quite possible that this body was purchased from another manufacturer, possibly even from Japan, a practice that increasingly occurred at the end of the ’60s. A similar practice happened in ’69 at Kapa, in Maryland. The Japanese bodies were just as good as the American ones and were cheaper. Whether this model, too, was ever offered in standard six-string or bass versions is unknown.

Roy Clark

Actually, there may be a connection between Holman/Alray and picking genius Roy Clark. In a November ’75 article in Guitar Player, Roy discusses his guitar collection. By the by, it’s pleasing to see that, at the time, he had both Gibson Super 400s and a Ventura L-5 copy! But there, against the dining room table, was a guitar identified as a Holman prototype, one of two “Designed by Roy but never marketed.” This was what we see as the Alray semi-solid Short Horn, with a bound head. Presuming the claim is correct, and we have no reason to doubt it, the new semi-solids were perhaps, at least in part, the brainchild of Roy Clark. Roy’s calling the guitar a Holman and his assertion that his “prototypes” were never marketed suggest this was probably developed before Holman-Woodell sold out to Modern Age in November of ’67. We do know that Clark visited the factory of several occasions, either participating in instrument design or having a guitar made to his specifications.

Indeed, the involvement of Roy Clark brings up a tantalizing suspicion about the seeming similarity between Alray semis and Kustom guitars, which debuted in 1968. As we know, Doyle Reading was involved in designing and producing the original Holman products and Bud Ross’ Kustom guitars. Clark briefly endorsed Kustom amplifiers around this time, so there’s a possibility he provided a direct or indirect additional link between the two companies from Kansas.

In any case, Alray guitars did not last long – a year at the most. It is also not known how many were made, but later evidence of the decreased number of employees suggests the number of these puppies is very low. Roy Clark’s calling his guitars prototypes also may serve as confirmation of our assumption that, despite the full-blown flyer, Alray guitars never made it very far. When’s the last time you played an Alray?

A new age

Holman-Woodell, Inc., appears to have struggled on until November 29, 1967, when the company was sold to another pair of owners, who changed the name to Modern Age, Inc., a name typical of the year of the Summer of Love! No mention is made of either Al or Ray in the press notices of the event, so it’s safe to assume they didn’t work out and were already gone by the time of the sale. The new owners were Lloyd Crumley, a native of Neodesha, and Burn Cersley, of Spokane, Washington, where he was associated with the 21st Century Music Company. As reported in the Neodesha Register, 21st Century had a guitar-organ combination product and planned to move production into the Holman factory, which remained at 5151/2 Main Street, “over the Davis Paint Store!” The plan was to liquidate all existing guitar stock and switch to guitar-organ manufacturing.

Presumably, it was this liquidated existing guitar stock that yielded the 21st Century 2 X 4s. No mention is made of Wurlitzer in the ’67 takeover notice, confirming our speculation that Wurlitzers were long-gone by this time. Since the Holman name drops from the company in late ’67, presumably ’67 would be the outside date on any Holman-brand guitars, too. No information exists on what constituted the 21st Century line, but it’s safe to assume that it was pretty much the same as Alray. Since none of these latter-day Holman products turns up in any quantities at all, production was probably down to bare bones by this time.

By the way, if you encounter a 21st Century guitar-organ, it will be housed in the Alray/Holman-Woodell thinline guitar. However, given the number of these babies that turn up in the vintage market, this idea, too, proved doomed.

Getting mistical

In any case, the Modern Age itself did not last long. By February, 1968, the Neodesha Register was saluting Neodesha’s latest new musical instrument manufacturing business, Mistic Music, Inc. Basically, this was a repackaging of Modern Age, with some infusion of new blood. Control was still held by Burn Cersley and Lloyd Crumley, with the addition of Lloyd Andrew. Plans to make and market a guitar/organ instrument continued as before, but plans now included making a “high-quality guitar” as well. These were to be distributed out of Washington. No mention of brand names, but a good guess would be these continued to be 21st Century guitars. Quite a bit shy of the 100 employees projected in the early days of Holman-Woodell, there were seven employees at Mistic in ’68, down from the 17 in ’66. How long Mistic Music survived is also a matter for speculation, but again the answer is probably not long, probably not beyond the end of the year.

Dating Holman etc. guitars

Guitars built by the Holman-Woodell factory came originally with a little metallic sticker with the factory name and a serial number stamped into it. There does not, however, appear to be any relationship between the serial number and the date of manufacture other than being consecutive. For example, the LaBaye 2 X 4 Six shown here has a serial number of #155540 and we know it is from 1967. Obviously there is no date code. The Holman Classic shown here is probably from 1966 and has a serial number of #155226. Assuming this dating is correct, 226 is before 540, suggesting sequential numbering and correlating to the time of manufacture, in that manner. Since each of the brands lasted probably a year, max (often much less), this is probably another of those academic questions, a moot point. About the only way to date them is roughly by pot date. The entire output of the factory only lasted from late 1965 to very early 1968, two and a half years at most. The chart of estimated dates included here should help you, but these dates must all be taken with a large grain of salt.

Finis

And that’s about all she wrote regarding Holman guitars from Kansas. As the ’70s began, the market shifted toward inexpensive Japanese copies of Gibson, Fender and Martin designs. There was little place for American-made, beginner-level guitars. Even though Holman-Woodell et al. promoted its guitars as “…for professionals,” they really rank as well-made, low-to-mid-range guitars, similar to better Kays or some of the other weirdness of the era, like Murphs or, for that matter, Kustoms.

No estimates are available on quantities, but, taken in toto, as it were, they were probably pretty small. After all, at its height, Holman-Woodell employed fewer than 20, and in later days fewer than 10. About the only models showing up these days are the Wurlitzers, followed by the odd Holman. 21st Century, Mistic (if that brand was ever even used) and Alray guitars are rare birds, indeed. As are the fabled LaBayes.

Still it’s a curious corner in the closet of American guitar history, and the next time you land on one of these guitars from Kansas, click your heels together and go for it.

Guitars of the Holman-Woodell factory

Here is a list of the known models of guitars and basses to have come from Neodesha, Kansas made by Holman-Woodell et al. Probably these are the only models produced, although you might encounter versions with different brand names, including Wurlitzer, LaBaye, Holman, 21st Century, Alray, and possibly Mistic, as well as one-offs and prototypes. These are, as we’ve seen, only estimates, so take them as a rough guide only.

Years available, Model

1965-66, Wurlitzer Cougar solidbody guitar (2510 white, 2511 red, 2512 sb)

1965-66, Wurlitzer Wildcat solidbody guitar (2520 white, 2521 red, 2522 sb)

1965-66, Wurlitzer Gemini solidbody guitar (2530 white, 2531 red, 2532 sb)

1966-67, Holman Classic solidbody guitar (or Cougar)

1966-67, Holman Wildcat solidbody guitar (or Traditional)

1966-67, Holman Gemini solidbody guitar (or Sting Ray)

1966-67, Holman “Long Horn” semi-solid guitar

1966-67, Holman “Long Horn” semi-solid bass

1967, LaBaye 2×4 “Six” solidbody

1967, LaBaye 2×4 “Four” solidbody bass

1967, Alray Classic solidbody guitar (Cougar)

1967, Alray Classic solidbody 12-string guitar (Cougar)

1967, Alray Classic solidbody bass (Cougar)

1967, Alray Traditional solidbody guitar (Wildcat)

1967, Alray Traditional solidbody 12-string guitar (Wildcat)

1967, Alray Traditional solidbody bass (Wildcat)

1967, Alray Sting Ray solidbody guitar (Gemini)

1967, Alray Sting Ray solidbody 12-string guitar (Gemini)

1967, Alray Sting Ray solidbody bass (Gemini)

1967, Alray Sting Ray semi-solid guitar (Gemini)

1967, Alray Sting Ray semi-solid 12-string guitar (Gemini)

1967, Alray Sting Ray semi-solid bass (Gemini)

1967, Alray Bob Cat semi-solid guitar (Cougar/Classic)

1967, Alray Bob Cat semi-solid 12-string guitar (Cougar/Classic)

1967, Alray Bob Cat semi-solid bass (Cougar/Classic)

1967, Alray Bob Cat semi-solid guitar (1 pu, Cougar/Classic)

1967, Alray Bob Cat semi-solid bass (1 pu, Cougar/Classic)

1967, Alray Short Horn semi-solid guitar

1967, Alray Short Horn semi-solid 12-string guitar

1967, Alray Short Horn semi-solid bass

1967, Alray Long Horn semi-solid guitar

1967, Alray Long Horn semi-solid 12-string guitar

1967, Alray Long Horn semi-solid bass

1967, Alray Acoustic Guitar

1967, Alray “thinline” 12-string guitar

1967-68, 21st Century (2×4 “Six”) solidbody guitar

1967-68, 21st Century (2×4 “Four”) solidbody bass

1967-68, 21st Century “Cougar” solidbody guitar

1967-68, 21st Century “Wildcat” solidbody guitar

1967-68, 21st Century “Gemini” solidbody guitar

1966-67 Holman Classic, same body as the Wurlitzer Cougar.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s July ’97 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.