In the early 1960s, a young Research Laboratory engineer named Roger Mayer filled his “spare time” hanging out with a jaw-dropping collection of up-and-comers on the fledgling London blues-rock scene, and building effects pedals for these future stars before most guitar players knew enough to ask, “What’s an effect pedal?” Though this would lead to one of the most famous artist-technician relationships of all time – as studio and tour tech for Jimi Hendrix – Mayer resolutely refuses to rest on those laurels, however legendary they may be.

Vintage Guitar: What first got you started on effects?

Roger Mayer: When I was growing up in southwest London in the early 1960s, I got to meet some of the guys who played in the local bands, like Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, and Eric Clapton. They were playing blues, and I play the guitar myself, so when I started hanging out with them we were always interested in what made the American records sound different.

We were listening to people like Freddie King, James Brown, and all kinds of music not a lot of other people were listening to, because it wasn’t on the radio. And even when I was still in school, I’d started making treble boosters and playing around with different guitar tones.

Were you studying electronics at the time?

I did six years of university, studying mechanical engineering and electrical engineering. Then I worked at the Admiralty Research Laboratories in Teddington, near where a lot of this music scene was happening in southwest London.

You were getting involved with the music scene even while you were still working there?

Oh, yeah. That was the day job, the night-time job being that I had a lot of friends who were professional musicians making different sounds.

Jimi Hendrix is clearly your most famous association. But who did you first build pedals for?

I suppose really it was Jimmy Page. He and Big Jim Sullivan in the early years. In fact, one of the fuzzboxes I designed and made in 1964 was on a number one hit record – the first recorded in England. Big Jim Sullivan played it on “Hold Me” by P.J. Proby.

I built a treble booster for Jeff Beck, and I was told that he borrowed Page’s fuzz box for some of the Yardbirds’ stuff. I believe I made a few things for Ritchie Blackmore of Deep Purple. There was also Steve Marriott, and of course, Syd Barrett from Pink Floyd.

Later, when I was really doing custom-made professional recording studio equipment, I made a lot of stuff for Ernie Isley of the Isley Brothers, and for the great reggae guys; I made distortions and Octavias and wah-wahs for Junior Marvin of The Wailers, and Bob Marley had one or two of my pedals. But I don’t think he used them on records. In more recent years, I made things for Stevie Ray Vaughan, Robin Trower, Joe Perry, Kenny Wayne Shepherd, and plenty of other guys.

Then, of course, there’s Jimi Hendrix…

Yeah. Working with these other guys in the mid 1960s and hanging out on the scene, I eventually met Jimi. We hit it off, and became good friends pretty quickly.

Hendrix couldn’t just go to a shop and pick up different boxes for different sounds, because they just weren’t there. But better than that, you were in the studio with him. What was that process like?

Basically, Jimi would have a particular song, and there would always be an emotion he wanted to portray in the song. Jimi and I would spend a lot of time around the flat or at the speakeasy discussing what sounds we might want to do. If you were going to use echo on it, that would be one sound. Or if you wanted the guitar to appear to disappear then come back… The sound you’re ultimately going to put on the record is going to depend on a couple of things: what the song’s about – you’re not going to put an inappropriate sound on it for that; and what key the song’s in. Because you can then voice the box differently. You might want to tune a wah differently for it…

Tuning in resonant frequencies and such – would you go as far as that?

Oh, yeah. We had one amp, two amps, we had multiple-path techniques of processing because we were only recording to four-track, so it had to be done pretty well immediately. I’d go back to the control room and have a listen, and then…

…And then get out your soldering iron!

Yeah, well (laughs)… We had the room at the back there, the maintenance room, where we could go and change that. But you’d take to the studio a few different things that you wouldn’t have onstage – different driving stages to put in front of the fuzz boxes, different equalizing stages, different voltages on the fuzz boxes. You’d segment the stages out. “Remember, we are only concerned with making a good sound on tape, and we’re going to use anything we can to get it.”

Even with all of Jimi’s experience, did you have to do anything special to create the mood in the studio, to get the atmosphere just right?

Up to even the Axis Bold As Love album, he was very shy in the studio. He didn’t think he could sing. All the lights would have to be out, he’d sing with his back to the control room, he was very shy. He needed a lot of encouragement.

One of my jobs with Jimi – technically, obviously, I could handle that side of it – was that you want three minutes or so of magic. That’s the end. The whole day has to lead up to that, whatever your job is – engineer or making the sandwiches or whatever – your objective is to capture 200 seconds of magic.

Jimi would cut a solo, and I might be sitting next to him on the floor of the studio, and he’d say, “Go and listen to that, Roger.” He wouldn’t even bother to come back in. I’d listen to it, and Jimi’d go on the intercom to the studio and go, “How was that?” Chas [Chandler] would go, “That’s great, Jimi, that’s a take.”

And then Jimi’d say to me, “What do you think?” I’d say, “Take one more, Jimi.” Then he’d do the actual solo, and people’s jaws would just drop. See, I knew him, and I knew what he could do. He was just messing around, and that solo wasn’t the one.

I guess Chas Chandler, Jimi’s producer, had some other considerations, too.

Yeah, well, Chas was always watching the wallet. Jimi would happily spend all day in the studio, but Chas was always in a hurry. Though Chas, as a producer in the studio, was very, very good.

The production work in the studio was between Chas and Jimi. I handled guitar sounds, and Eddie Kramer really was the engineer. He had no idea what the song was going to be until Jimi was finished with it. No one did, really. Then they totally couldn’t believe it, because we were breaking new ground.

Clearly, requirements in the studio were entirely different from the requirements for live work.

The important thing in the beginning was actually producing the sound to be on the record. Because once you’ve got it on the record, people can play it at any level and it’s going to sound right. So I started off making stuff that was used on records. It obviously worked live, as well, but that’s really what I’m probably most known for – making pedals and devices that were used on records.

Let’s look a little more at your broader career as a pedal maker. What was your first commercial product? Was it the Octavia?

Well, I never originally offered that commercially as such. I made them for a few select people. They were like prototypes.

So you didn’t offer a line of pedals until you brought them back, almost as reissues of your custom devices for these players?

Well, I was working with Jimi, and when I made the Octavia for him, we made half a dozen or so. But when I went to live in America in 1969, I went straight into manufacturing recording studio electronics.

I was making studio consoles and equalizers, and was involved in the startup of the Record Plant and Electric Ladyland and all that sort of stuff, so I wasn’t into making little guitar boxes. The only time we’d make a few guitar boxes for people would be for famous players, not anything available commercially in a music store.

There was a period in America, after Jimi’s death and up to the early ’80s, where he wasn’t popular. It was disco music and this and that. Guitar music wasn’t at all popular. I was doing specialized work for bands like the Isley Brothers, in the studio, making pedals for Ernie. Then I went down to do the stuff with Bob Marley.

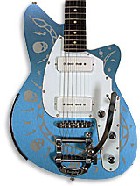

It got to about 1980 or so and people started to ask for my effects a bit more, and that’s when I designed the rocket-shaped enclosure.

Which is now such a distinct thing.

It’s an icon, really. I designed it because I wanted to have a pedal that when anyone looked at it, they knew it was mine. You didn’t have to put any writing on the box. And the shape of the rocket has a lot of ergonomic considerations; it’s got the fins on the back that protect the knobs from anyone putting their foot on them, you can drop the box and never hit the knobs, and you can also hit the footswitch from any angle – back, front, sideways.

What did you first put into that enclosure?

The Octavia. But when we first made it, we did it with an optical switch; it didn’t have a snap-action switch in it. We put those out, and some people liked the snap action of the switch. So we changed it.

And your stuff’s been more or less available since?

Yeah, since the early ’80s. We had the Axis Fuzz, a Metal Fuzz, and the Mongoose pedal.

It seems you’ve had something of a boom again, recently.

When we came back to England (in ’89), I stopped making specialized rackmount equipment, and concentrated on worldwide distribution. Japan has always been our biggest customer. We’re probably number six for pedal makers in the whole of Japan.

What do you think of today’s “boutique” pedal market?

Boutique pedal market? I don’t consider myself in that market. Most designers aren’t doing anything new. They’re not putting any R&D into it, they’re not designing their own enclosures, and they’re not making anything new. And I’m getting tired of being ripped off.

But because you were one of the first pedal makers, it’s probably hard to follow you without building an effect that’s at least vaguely similar to one of yours.

Yeah, but what I’m saying is they’re really not taking it any further. And it’s bad to continuously go back to the past, and not evolve. That’s not investing in the future. In any publicity, I’ve never said that all we do is make a version of our old pedals. We’re constantly evolving, using new components. We never make a feature out of using an old component, because most old components were horrible. They are better today.

Many people make a big deal about dredging out vintage germanium transistors or carbon-comp resistors…

We use germanium transistors in a couple of designs, but you’ve got to buy thousands of them, then sit and test them all, and you’ll come up with a small percentage that are any good. As for carbon-comp versus metal film resistors, there’s nothing in the composition of a resistor that’s going to add or subtract any harmonics to the signal.

So what are your own goals as a designer?

You want a tone that’s organic. And it’s so easy to build a fuzz box or a distortion type of box – you’ve got many boxes that, to be frank, you put a guitar into them and you wouldn’t know what type of guitar it is. The whole tonal quality of that guitar just disappears. It’s got “brick wall” processing in it, and this is ever so true of some of the cheaper multi-effects processors. Horrendous!

Do you feel you’re best-known for any one particular pedal?

I suppose the most unique pedal is the Octavia, which is the frequency-doubling effect Jimi first used on “Purple Haze.” And that’s the one that’s probably been ripped off the most.

Had anybody done anything like that before you?

Nah. I was just thinking about different electronic techniques for doubling a frequency, and I came across a technique that, looking at it simplistically, it almost acts like a mirror. It doubles the number of images of the note. And that, apparently, makes it sound twice the pitch. And because the sound wave is going up and down twice as much, even though you’ve changed the relationship of it, the ear perceives it as twice the frequency, although it isn’t. It’s much like putting a picture up to a mirror and seeing two of them, but there’s still only one picture.

Do you ever wish you’d put out the Octavia commercially yourself back in the late 1960s?

No. I had my other work, and besides, the interesting thing is that the copies never quite did it right. But I’ve got no sour grapes about any of that. The one matter about infringing the copyright, though, is they should at least pay respect, you know? If you’re making a copy of something, don’t tell me the copy’s better than the original.

What has excited you the most of your newer designs.

We released an updated Octavia, the Concorde+ treble booster, and the Voodoo Vibe Jr. in the new Vision enclosure last year. The enclosure has both a hard-wired output, and two buffered outputs, so the player can choose whichever is best for his applications, or use both buffered outs together. As for the Vibe Jr., it has the same main circuit as the big Voodoo Vibe, with the same carefully selected light cells, so the sound is all there, but the control functions are simpler, so we can sell it for a lot less. It’s all an evolution of my modifications to Jimi’s own Uni-Vibes, with further improvements to make them quieter and more stable.

You recently released a version of your very first fuzz box, the one you made for Jimmy Page.

Yeah, it’s called the Page 1, and it’s also in the new Vision enclosure. The one I originally built for Page was loosely based on the Gibson Maestro (Fuzz-Tone), and the Page 1 uses the same main circuit with a pair of selected AC128 germanium transistors. But it has been vastly improved for noise, I have added a very useful Tone control, it has a circuit in it to operate off a positive power supply rather than the negative supply they used to require, and because it’s in the Vision enclosure it has the three outputs and all those other benefits.

What does it sound like?

It’s a cool pedal, but it’s definitely a 1960s fuzz sound. The unit has a gating effect within the amplifier – it doesn’t have a lot of sustain like modern rock or metal fuzzes; it’s a very percussive effect, and it reacts very well to the way you’re playing.

Out of all these, though, the thing I am probably most excited about at the moment is the new guitar-strap remote effects controller I’m developing. This has never been done before, and it has a lot of potential.

What does the remote controller do? How does it work?

It consists of a transmitter unit mounted on the guitar strap, with a receiver unit on the floor next to the effects set-up. The Vision has two loops for switching pedals. Buttons on the controller allow the guitarist to trigger one or both loops remotely to instantly change sounds without having to run back to the pedalboard, and without breaking eye contact with the audience. The transmitter uses code-hopping technology that changes each time you hit the button, so no one can scan it and break into the code, and the receiver can learn up to seven controllers, so you can have multiple transmitters for different guitars.

The first unit will be the Roger Mayer Skull Controller, with the transmitter housed in a small metal skull, which is a very iconic shape. It’s great for the rock and metal players. Then we will also release the transmitter in different enclosures, to suit the different tastes and budgets. We should begin rolling that one out early in the new year.

Do you think Jimi would have gone for one of these controllers?

Yeah. He’d have loved to use something to make performance easier and bring control to him and help him not look stupid – rather than cool – whilst changing tone, as he was the consummate guitar showman.

Do you ever think back and maybe miss the heyday of working with Hendrix?

The thing I miss probably most about Jimi is that he was up for anything. If you came up with a new idea and it appealed to him and he could imagine it, he’d say, “Let’s do it!” The enthusiasm he exhibited for doing something new and exciting and innovative was great.

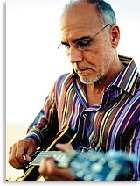

Roger Mayer with his latest pedal, the Spitfire. Photo: Dave Hunter.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Aug. ’05 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

.jpg)