For the past decade, Nashville’s own Richard Bennett has been a touring guitarist for Mark Knopfler. The gig is just the latest installment in a long and varied career that has seen Bennett wear the hats of session veteran, record producer, and touring side man.

Prior to the Knopfler gig, Bennett spent 17 years as a guitarist on tours with Neil Diamond, and in the studio he has worked with everyone from Billy Joel and Barbara Streisand to Rodney Crowell and Vince Gill, and produced Grammy Award-winning artists including Steve Earle, Emmylou Harris, and Marty Stuart.

Bennett’s career started humbly. In the late 1960s, his first gigs were in Phoenix bars before he was taken under the wing of session legend Al Casey. The relationship led to Bennett spending 15 years as a sessioneer in Los Angeles, and then touring with Diamond. In 1985, he moved to Nashville and changed his focus to production, working on several high-profile albums including seminal Guitar Town by Steve Earle and Live at The Ryman by Emmylou Harris and the Nash Ramblers.

In ’94, he did his first sessions for Knopfler. The album and subsequent tour reinvigorated his love for the guitar, and his most recent work has been with Gill and new country star Miranda Lambert.

Bennett is currently cutting an album with Casey, and preparing to tour with Knopfler and Harris in support of their soon-to-be-released duets album.

Vintage Guitar: What inspired you to pick up the guitar in the first place?

Richard Bennett: I suppose hillbilly music, really. I came up listening to early-’50s hillbilly music – Lefty Frizzell, Hank Williams, and Johnny Horton… Hank Thompson, Hank Snow.

So, did you start on lap steel or standard guitar?

It was a regular Spanish-style guitar. There was Elvis on the Dorsey show, and the Ed Sullivan shows from when I was a kid. That’s when I said “I want to play that instrument.”

So, what age were you when you finally got that guitar?

I got my first guitar when I was 11. We were living in Phoenix, and my folks used to occasionally go to McAllister on weekends, just across the border in Mexico. They bought me a little Mexican guitar, which I still have hanging on my wall.

Who was your first teacher?

A guy named Forrest Skaggs. He was the kingpin Western bandleader in Phoenix from the late 1940s on through the ’50s. By the time I started taking lessons in ’62, he was playing only weekends. In his store, the walls were lined with 8×10″ photos autographed by George Jones, Johnny Horton, Tex Ritter, Eddie Dean, Ricky Nelson… all of them. In the ’50s he had a Saturday-night barn dance show called the “Arizona Hayride.” It was at a boxing ring, and whenever [those guys] were near the Phoenix area, they came and played the “Hayride.” I went to his store with my guitar and my mom a couple days after I got the guitar, and the walls were lined with 8×10 glossies autographed by George Jones, Johnny Horton, Tex Ritter, Eddie Dean, Ricky Nelson – all of them. I knew that was the place to be taking lessons.

Forrest was a great Hawaiian-style player. He knew Sol Hoopii, and Dick McIntire. All those guys who had moved to the West Coast. He was living on the West Coast from the ’30s into the early ’40s – there was that mass migration of Hawaiians coming to Hollywood because that music was huge. They were making movies and records, and he knew all of them. So I suppose that was where my love of Hawaiian music came from. And I still kind of play old Dick McIntire-style Hawaiian guitar.

What was your first professional gig?

It was probably with Skaggs because he was working weekends, and if he felt you showed promise, he’d drag you along on a gig and let you play a few tunes. Shortly after that, I got a weekend gig at Mack and Marge’s Snack Inn, near the slaughterhouse in South Phoenix. It was a horrible place – literally, a chickenwire place. All of the roughnecks would go there, and it was every horror you could imagine. Fights would break out, cue sticks and horrible stuff. People on the fringe of society. I was thrilled to be there, even though I couldn’t even drive yet. My parents would drive me down, dump me off, and come back to get me at 1 a.m.

How old were you?

I was probably 15. My parents, bless them, allowed me to go do that, and it was the greatest thing. Six bucks a night, and I was thrilled to get it.

What kind of music were you playing?

In that place, it was country. But I was the kid in the band – the youngest guy other than me was probably 40. So it wasn’t even country music of the ’60s, it was country music of their youth; ’40s and ’50s country. That’s what I grew up playing… and Hawaiian music. I had the weirdest upbringing. I just didn’t come up playing rock and roll like everyone else.

What gear were you using at the time?

I had just got a guitar made in California for a couple years called a Bartell. That and a little Fender student-model steel guitar I’d play on some tunes. Shortly after that, I got a little Fender 400 pedal-steel, and learned to play it out on the gig.

I did that gig at the Snake Inn for about a year. It was great, and I’ll never forget it. But it was a horrible place.

What came after the Snake Inn?

A series of marginally higher-class gigs. I played a few cocktail lounges, but mainly country gigs, all of them great experiences.

What was the next step?

My big break was the fact that Forrest Skaggs taught a player by the name of Al Casey about 15 years earlier. Al, at that point in the ’60s, was a first-call L.A. session guy. Unbeknownst to me, I was a huge fan before I knew the name or who he was. He played on “The Fool” by Sanford Clark, and “Endless Sleep.” Those were wonderful records, and I remember not being able to wait until they played those songs on the radio. So, after a little time taking lessons with Forrest, the name Al Casey kept coming up. It turned out that Al’s folks still lived in Phoenix, and Al would come to town at least once a year. So I met Al through Forrest, and Al took me under his wing. That was my biggest break of all.

I spent a summer in Hollywood, with Al, before I actually moved to the West Coast. I got to meet all the guys – James Burton, Joe Osborn, Hal Blaine, all of them because Al had a little music store. I was the kid hanging around, and they were so good to me.

By the time I graduated from high school and moved to L.A. in the summer of ’69 with the intention of getting into studio work, I had a place to go, to work, and to teach. The studio thing fell together quickly for me, and it was at that point that I was getting tired of country music. I didn’t like what it sounded like. So, I threw myself into pop music, which was the bulk of what was being done there.

When do you do your first session?

That had happened in the summer of ’68, when I was tagging along to sessions with Al. It was like a bad B movie; there were three guitar players booked, and only two showed up. So they handed me a guitar, and there I was on my first Hollywood session – thrown into the deep end.

When you moved to L.A. which guitars did you have?

I had a ’65 Fender Esquire Custom, an Ampeg amp, a Fender 400 pedal steel, and a ’30s National guitar. Then, after watching other session players and Al, I started amassing stuff I thought I’d need – a “kit.” In those days, there was no such thing as being an “acoustic guitar player” or “electric guitar player,” you had to play everything. You had to be a rhythm-guitar playe and you had to be a lead player. Whatever else you could strum on – ukulele, Hawaiian guitar, tiple, banjo – whatever it was, you took it with you. If you were the tenor-banjo guy, you were a hero even if you couldn’t play it that well. You’d become known as a multi-instrumentalist. So, I got a cheap little Japanese gut-string, then whatever I could get my hands on. To this day, I carry weird stuff and play odd, ethnic instruments. They all come in handy.

Did cartage exist in the late 1960s?

It was just starting. One night in Al’s store, there was this rumbling about cartage. The guys were really nervous because they were afraid they’d lose accounts if they tacked on another $40 for delivery. Al organized a meeting with Hal Blaine, James Burton, Joe Osborne, and a bunch of the guys. They decided they all had to do it, or all let it go. After much hemming and hawing, they decided to try it. But prior to that, everyone just loaded up their trunks. And they all drove Cadillacs, not necessarily because they loved them, but because they had trunks that could hold eight or nine guitars and a Princeton amp. Barney Kessell’s favorite line when asked about the hardest thing about studio work was, “Finding a good parking spot.” By ’71, I had a cartage trunk.

How did your session playing progress?

Well, I was one of the young kids coming up with Larry Carlton and Dean Parks. Then, a drummer friend of mine, Dennis St. John, got a call to do gigs with Neil Diamond. At first he didn’t want to because he was doing a fair bit of session work. He had recently moved to L.A. from Atlanta with bassist Emory Gordy, and they’d done a lot of recording in Atlanta. They kept calling him for the Neil thing, and he ended up doing a few weekends, and really liked it. After a couple of months, Dennis pulled Neil’s sleeve, and said, “I’ve got a group of musicians I work with and I think it’s time you improve your band.”

So Neil came to a session and that was it. No audition, we just went to work rehearsing. Our first gigs were March or April of ’71, and I immediately began recording with him because I was a little more on my way in Hollywood. When I think about it, it’s amazing how I’ve just fallen into things.

What was the first Diamond record you played on?

I played on a couple songs on Stones. The first full album I played on was called Moods, which had songs like “Song Sung Blue,” and “Play Me.”

I played on all of Neil’s records through ’87, when I left to pursue production and session work. It was a great association, and I learned so much from him about putting together songs, arrangements, and records. He took a long-term lease on what used to be the Liberty studio, in West Hollywood. We used it to rehearse, and he would often come in with the barest of ideas – a chord sketch or a bit of melody. I learned about working sections of a song, and how to tear a tune apart, and putting it together in different ways. Neil is a master at that.

I also learned a lot about being on tour and on stage – your focus, how to present yourself. It was a great finishing school, and we ended up writing a handful of tunes together, one was “Forever in Blue Jeans.” He was very patient with my crappy ideas, bless him. I think the world of him.

What were you using, gear-wise, at that time?

My touring rig was a Yamaha SG 2000 and a silverface Fender Twin.

What was one of your favorite sessions of the ’70s?

One that stands out is playing on “Captain Jack,” from Billy Joel’s Piano Man album. I overdubbed a Danelectro six-string bass on the chorus, doubling the guitar line. It gave the song a lot more punch. This was at a time when no one was really using those instruments.

In the early ’80s, you played on records by Rodney Crowell and Rosanne Cash.

That was through Emory Gordy, who was playing with Rodney, and they both played in Emmylou’s Hot Band. I toured with Rodney and Rosanne as part of the Cherry Bombs, which had a rotating guitar chair with myself, Albert Lee, or Vince Gill. Playing on their records led to my first sessions in Nashville, which was about 1982. I began flying to sessions for Emory, Tony Brown, and Jimmy Bowen. I liked the way they cut records, because it was the way we used to cut in Hollywood – six or seven guys in a room, making a record. L.A. was becoming very piecemeal and very keyboard-oriented. Those sessions made me start to consider moving to Nashville. The Neil thing was secure, but I thought of myself as a session guy first and enjoyed what we did here.

What really got me to move was working on the Steve Earle record, Guitar Town. Steve wanted me involved, and asked, “Why don’t you just move?” It was a snap decision. I moved to town in ’85, did Guitar Town, and began establishing myself as a session player in Nashville.

You played the signature tick-tack lick on “Guitar Town.”

Yes, I played it on that Danelectro six-string bass.

Doing that album opened a lot of doors for me, in session playing and production. I moved because I was antsy to produce, and that album was a good coming-out party.

How did you end up leaving Neil?

When I started producing, I had deadlines. And I couldn’t take off for a month to play shows. They got Hadley Hockensmith to fill in, and it evolved to become his gig. I never was fired, never had to quit.

Who did you produce after Steve Earle?

I produced a couple records by Marty Stuart and Emmylou Harris in the early ’90s. I was very proud of Emmy’s Nash Ramblers and Bluebird albums.

Did you play on them?

Yes. A lot of people don’t like to play and produce, but I don’t mind it. As a musician, when you’re on the floor, you have a pretty good sense of whether the take is happening. Not always – there are times when you listen down and its crap – but most of the time, your instinct is correct.

Do you still work with Emmylou?

I have off and on. I played on a cut on Wrecking Ball, and on the Mark Knopfler/Emmylou Harris duets album. I love working with Emmy, but she’s been working with Buddy Miller, who is a great player. Every now and again I end up on something with Emmy. I cherish that working relationship and friendship.

Your ’65 Telecaster has a string bender.

It’s actually a Custom Esquire that I took to Fender, had a neck pickup added, and had the headstock logo changed. I later had the bender installed by Dave Evans. He calls it a “pull string.”

Have you done much bender playing on record?

Not a whole lot. I played some for an artist I produced for Capital, George Ducas, on a cut called “Teardrops.”

How did you start working with Mark Knopfler?

Much of that is due to songwriter Paul Kennerley. Mark had started spending time here, initially because of Chet Atkins, and the Straits thing had finally been packed up in the attic. He was recording with the thought of his first solo album. He had done some recording in Ireland and Louisiana, just trying things out. He stopped here, and Paul recommended me, as did producer Chuck Ainlay and steel guitarist Paul Franklin.

Mark was very concerned about “the other” guitar player. He wasn’t looking for a bunch of fancy licks, just a good feel, and was a bit concerned that I’d played with Neil Diamond and the fact I was a session guy. So we cut a couple sides, and that was it. A couple months later, Chuck called to book more sessions with Mark. We fit together well musically and personally. I know how to be a good second banana – I’ve done it all my life.

How much direction did Mark give?

Next to none. I think he was at a point where he felt secure enough to let go. He became more “Let’s see what you can give me,” instead of making you try to play like him. Sometimes, he’ll give a little direction, such as “Think about a certain era.” Which is helpful. It’s very flattering, really.

The sessions became the Golden Heart album. Talk about the opening chords to “Rudiger.”

That was my Gretsch 65 from the late ’30s. I played it on one of the takes, and he loved it. That was one of the first sessions I played on for him, and it really helped set the tone for our work together.

After the Golden Heart tour, did you go back to producing?

Yes. I produced a couple of albums I was very proud of that did nothing at radio. One was by Kim Richey, another was with George Ducas.

I was getting frustrated, and really let my playing take a back seat through 10 years of producing. I was no longer thinking of myself as a guitar player first. So, when the Knopfler thing happened, it made me realize that one, I wasn’t ready to let go of being a musician, and two, how crappy I’d become. I was onstage with one of the great living musicians, who happened to play the same instrument I did, and I was struggling at every turn. It was a difficult tour for me, but Mark never said boo about it.

I did a lot of serious self-examination on that tour, and when it was over, I pulled myself up by the bootstraps. For the first time since I was a kid, I seriously began practicing, wanting to improve myself. I had a great role model in Mark, and I hadn’t had one in a long time. All of my role models were dead. But here was a contemporary I looked up to. It was really a reawakening.

What material did you use to practice with?

Chord-scale books. It was like going to the gym. I also dipped back into the Mickey Baker books. I started writing what became the Themes From A Rainy Decade album. I decided to do something that wasn’t your typical guitar wank. Most of those records are terribly impressive for the first listen or so, but you can’t hum any of it. I began listening to Tony Mattola, Al Caiola, and I had always listened to Chet. Tony, in particular, was just a stunning guitar player. Also, Hank and the Shadows. And I thought “Who’s doing that now?” No one.

So you played with Mark up to his most recent album, Shangri La.

Yes, played a couple records and soundtracks. We recorded at Shangri La studio, in Zuma Beach – The Band’s hangout on the West Coast. Mark had the great idea to use fewer instruments, so we limited the number of guitars – Mark’s ’53 Southern Jumbo for the acoustic tracks, a ’56 6120, a Knopfler Strat, a ’64 Jazzmaster, and a National.

How much pre-production did you do for the Shangri La tour?

We rehearsed for about three weeks, two of which were nuts and bolts re-learning the tunes. Then, we did a third week on a soundstage to do lights and get the set together. For the first tour, in ’96, we rehearsed for about six weeks.

Did you have freedom on the Dire Straits songs, or were you required to play parts like on the record?

A bit of both. I did the things I felt were important markers. On some songs, like “Brothers in Arms,” I play a 12-string picking part. And on some songs, we have returned to the original arrangements. On “Sultans of Swing,” we go back down to a four-piece, and copy the record. On “Money for Nothing,” I play cowbell!

What was your setup for this last tour with Mark?

A ’54 Tele, Knopfler Strat, Martin 12-string, OM-28, Flatiron Bouzouki, my old Gretsch 65 – Mark’s ’57 6120s, a late-’20s National, Mark’s ’54 Strat, and a ’54 tribute Strat. I used a volume pedal, Hot Cake overdrive, Dunlop tremolo, and a Boss delay. I used a Vox AC30.

What have you been up to since the Knopfler tour?

I got a call to play on cuts for Vince Gill. He’s such a lyrical player. I also played on Rodney Crowell’s The Outsider, and the album by Miranda Lambert. I’m beginning to cut another instrumental record. There is, of course, the upcoming Mark and Emmylou tour, and then another Knopfler record later in the year.

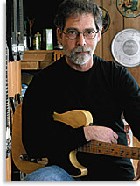

Bennett and his early-’54 Telecaster. Photo by Rusty Russell

This article originally appeared in VG‘s June ’06 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.