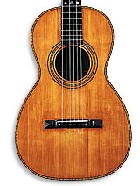

Way before “unplugged” became a popular way to play music and fretted acoustic bass guitar (ABG) models began appearing from so many manufacturers and independent luthiers, Ernie Ball bought a Mexican guitarron and gave it frets. Unable to interest manufacturers in the viability of an acoustic bass in the early 1970s, the veteran musician, retailer, and stringmaker created one himself.

There were, of course, prior attempts at making and marketing an acoustic bass. Gibson’s humongous Style J mandobass was made from 1912 to circa 1930 and had a 42″ scale (same as an upright bass). Four decades after the demise of the mandobass, Ball’s short-lived attempt at a true acoustic bass guitar was innovative and eyecatching – and ahead of its time. Guitar manufacturing legend George Fullerton (Leo Fender’s right-hand man for decades) departed the Fender company five years after it was acquired by CBS, then worked with Ball to create the prototype acoustic bass. They hit the market in 1972.

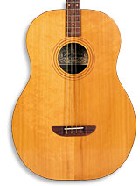

Perhaps the most intriguing facet of the Earthwood acoustic bass models was that wood was used wherever possible, including places where plastic or metal may have been more typical. On the latter-day example shown here, the truss rod cover, body, and headstock binding, fret markers, and soundhole trim are all wood. Note the flame maple overlay on the headstock, and Schaller tuners. And there were variants of the ABG, including bodies of different depths – 65/8″ and 81?4″. The model shown is shallower, and many examples had maple fretboards and/or wood pickguards.

The top of #1021 is two-piece spruce. Its body is 25″ tall and 183?4″ wide at the lower bout. The sides are made from two pieces of bookmatched mahogany that flare in opposite directions from center vertical strips of wood at the top and bottom of the body. The back is two-piece bookmatched mahogany, as well. The maple neck is bolted on, and a small panel on the back covers the three neck bolts as well as (surprise!) a tilt-neck adjustment access hole for an Allen wrench. The instrument’s serial number is stamped on the assembly that houses the neck bolts inside the body.

The scale on this beast is a full 34″ standard length, and the strings have to be loaded through the soundhole, then through the holes in the bridge. Moreover, this example is technically an electric instrument – there’s a Barcus-Berry Hot Dot pickup mounted under the bridge, and the cord for amplification plugs into the large lower strap button. There are, however, no controls – no volume, tone, equalizer, or active circuitry of any kind. The general line of thought for a player whenever one of these was wired up was probably to hope like hell it didn’t feed back (which it has a propensity to do when amplified).

For most would-be players, terms like “cumbersome” or “ergonomically-challenged” don’t even begin to describe the reaction when you first sit to plunk on an Earthwood bass, but then the guitarron on which it was based isn’t exactly sleek and slim, either.

Nevertheless, these gargantuan instruments can generate a generous and resonant sound once (and if) a player becomes accustomed to the bulkiness. It can add a unique (usually appreciated) low-end to any pickin’ and grinnin’ session in nearly any acoustic-oriented genre… and it’s still a lot smaller than a doghouse bass!

These days, improvements in piezo pickup technology and active circuitry have made it possible for the bodies of modern acoustic basses to be the same size as their guitar counterparts… as long as they’re running through an amplifier. But an Earthwood bass, considering the immense size of its body, moves a whole lot of air, so it’s more than capable of holding its own in a purely acoustic environment, as notable players like the Who’s John Entwistle and the Violent Femmes’ Brian Ritchie could attest.

For slightly over a decade, amidst stops and starts for various reasons, the Earthwood acoustic bass and other Earthwood instruments were created and produced sporadically until 1985. The brand name lives on for the Ernie Ball company, and currently serves as the moniker for its #2070 phosphor-bronze acoustic bass strings.

The quantity of Earthwood basses made is nebulous, but they are relatively rare – and big – birds.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Aug ’05 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

.jpg)