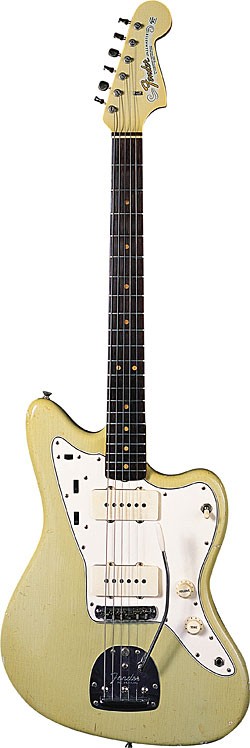

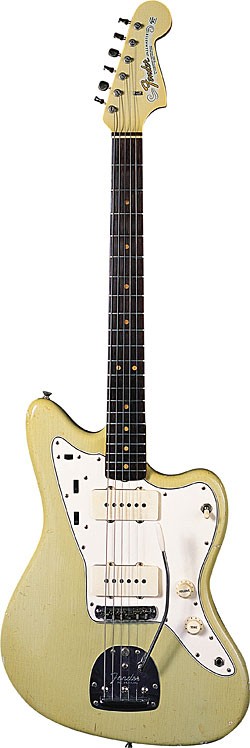

A 1965 Fender Jazzmaster in Surf Green. Photo: VG Archive.

In the midst of its scramble to compete with Fender by developing the radical Flying V and Explorer guitars, Gibson likely didn’t realize that Leo Fender was similarly trying to loosen its grip on the jazz guitar market of the late 1950s.

At the time, Gibson’s grasp on the segment was indeed firm. Its hollow and semi-hollowbody electrics, along with the introduction of the warm, midrangey humbucking pickup combined to give most jazz players exactly what they were looking for in terms of feel, tone, and playability. Plus, among the hoity-toity jazzer set, Gibson guitars were “serious” instruments, with their glued-in necks, binding, and fancy headstocks. Fenders? Those were for “rockers” and garage bands!

Watching and hearing what Gibson had going on, Leo Fender thought he had to do something. If country, rock, and studio players were enamored with his hugely popular Telecaster and Stratocaster models, surely he could build something jazz players could love.

So it was that in 1957, Leo began tinkering on a design that would go beyond anything he’d previously attempted. He started by changing the body, giving it different curves and a bit more size. Bouts featured softer corners, and the instrument’s “waist” was offset slightly, so if a player preferred to sit down, it would balance comfortably. Leo believed high-brow or old-school players sat while they played, and he wanted the body to be comfortable in that position (it must have been an important element given the patent application contained drawings of a man sitting in two positions, Jazzmaster snugly in place). He also incorporated the Strat’s beveled back and arm contours, which were one key to that model’s popularity.

Perhaps in an attempt to emulate the tones of Gibson’s patented humbucking pickups, Leo opted to equip the Jazzmaster with pickups that had wider, flatter coils. With an aesthetic borrowed from his early steel guitar designs, in terms of size they did bear a resemblance to Gibson’s units. But that was where the similarity ended. Their white covers and centered polepieces made it unlikely they’d be confused. And plugging in would erase any doubt.

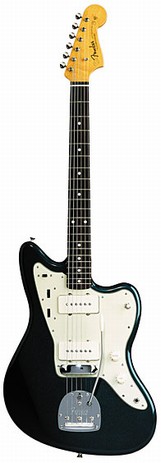

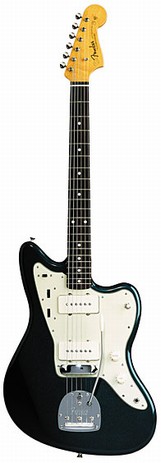

A 1963 Fender Jazzmaster in Burgundy Mist. Photo: Michael Tamborrino/VG Archive.

There was more “newness” to the Jazzmaster. Arguably the most useful and important was its pickup-switching system, which utilized separate circuits for regular and rhythm settings. Developed by industrial engineer Forrest White (Fender General Manager from May, 1953, to December, 1967) for a hobby guitar he built in 1942, the circuit was engaged via a slider switch above the neck pickup; the second setting let the player roll off his treble and volume (like a jazzer comping behind a bandmate’s solo) without touching either knob. The Jazzmaster was the first production Fender guitar with such capability.

It was also the first to sport Leo’s new floating vibrato and floating bridge. In this design, the strings went over the bridge and attached to the vibrato tailpiece. This length of string served to limit sustain, furthering the guitar’s pursuit of jazz tone. The bridge’s two pointed anchor posts rest on metal cups sunk into the body. By pivoting on these pointed legs, the bridge could move along with the strings when the vibrato was deployed. The setup effectively limited friction on the strings, but the bridge design left something to be desired.

The final new mechanical element was the Jazzmaster’s “Trem-lock,” which allowed the guitar to function in a vibrato-free mode and boasted the added function of holding the guitar in tune even if a string popped while the guitar was played. Thing is, if you bought a Jazzmaster, chances are you used the vibrato, so this feature was of limited functionality.

Speaking of the vibrato… Leo designed the unit for use with the heavy-gauge strings that were more popular in the ’50s. It was best manipulated by a player who didn’t lean too heavily into the vibrato arm – the lighter the touch, the better. And if you preferred lighter strings and/or got on the bar a little too much, the strings often popped out of their grooves in the bridge saddles. This factoid led more than a few Jazzmaster owners to swap the guitar’s bridge for (of all things) a Gibson Tune-O-Matic, despite the fact it didn’t match the Fender’s fretboard radius. Plus, when compared to the Strat’s smoother, more mechanically functional vibrato, the Jazzmaster’s had a limited range of pitch adjustment,

Audience Reaction

When Fender reps began to show the Jazzmaster to some of the players they hoped would raise its profile, reaction wasn’t particularly favorable. Some of the biggest names in jazz, including Wes Montgomery, Tal Farlow, and Jim Hall, noodled on it but showed little or no interest in making the model part of their regular instrument lineups.

A prototype Jazzmaster, with black pickguard and matching pickups. Photo: VG Archive.

But for better or worse it did catch on with younger players, with Southern California’s emerging garage band crowd showing the most interest. Perhaps the most important single player was Bob Bogle, guitarist with the instrumental/surf combo The Ventures, one of the foremost bands of the early 1960s. In fact, the song most associated with that band (and the surf music genre, in general) is the band’s number two hit from 1960, “Walk Don’t Run,” which featured then-lead guitarist Bob Bogle on a Jazzmaster. Later, rhythm guitarist Don Wilson would also make heavy use of the model, ensuring that most Ventures music did indeed sport its not-so-jazz-like tones, at least until the band signed an endorsement deal with Semi Moseley’s new Mosrite brand.

Another major-league Jazzmaster player was Carl Wilson, with The Beach Boys. Yes, they were renowned for their vocal harmonies, but the band’s early albums were also noted for their production, including the way they displayed Wilson’s guitar tones.

As the ’60s became the ’70s, the Jazzmaster continued to find a home amongst rock guitarists of many styles. Toward the middle of the decade, it was popular with the minimalist new wave and punk players. Elvis Costello arguably carried the highest profile amongst them, and the Jazzmaster was his trademark instrument. Though Costello is more noted for his songwriting, his guitar work is a pleasant bonus. His 1977 debut album, My Aim is True, offers a sample.

Also in ’77, Tom Verlaine played a Jazzmaster on Television’s debut record, Marquee Moon. Along with co-guitarist Richard Lloyd (VG, May, ’03), he introduced an innovative, technical element to their punk lead/rhythm playing that proved highly influential.

Then there was Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore, who continued the tradition of non-mainstream preference for the Jazzmaster on his band’s landmark ’88 album, Daydream Nation. His deconstructive style been a notable influence on alternative rockers ever since.

And more recently, Greg Camp, guitarist with pop sensation Smashmouth, has used the Jazzmaster to augment his band’s ’50s retro/surf sounds.

So, perhaps saved by its versatility and a handful of influential artists, the Jazzmaster – chronic underachiever in the eyes of its creators – survived in Fender’s product line until 1980. And it was reborn in ’96, when the company saw sufficient demand to add an imported version to its lineup of reissues.

Fender’s ’62 Jazzmaster reissue. Photo courtesy of Fender.

American Vintage ’62 Jazzmaster

Fender’s current, American-made reissue ’62 Jazzmaster remains true to the original. It features a contoured body with offset waist, switchable lead and rhythm circuits with independent volume and tone controls, and floating tremolo with “Tremolo-Lock.”

| Body: |

|

Alder |

| Neck: |

|

Maple, “C” Shape with nitrocellulose lacquer finish. |

| Fingerboard: |

|

Rosewood, 7.25″ Radius. |

| Number of Frets: |

|

21 |

| Pickups: |

|

Two Special Design American Vintage Jazzmaster single-coils |

| Controls: |

|

:Lead” Circuit: Volume, Tone, “Rhythm” Circuit: Volume, Tone |

| Bridge: |

|

Vintage Style “Floating” Tremolo with Tremolo Lock Button. |

| Pickup Switching: |

|

Position Toggle: Position 1. Bridge Pickup Position 2. Bridge and Neck Pickups Position 3. Neck Pickup two-position slide: Up: Lead Tone Circuit; Down: Rhythm Tone Circuit. |

| Hardware: |

|

Chrome |

| Scale length: |

|

25.5″ |

| Width at nut: |

|

1.65″ |

| Introduced: |

|

July, 1999 |

Jazzmaster Values and Collectibility

When it debuted in Fender’s catalog in 1958, the Jazzmaster was the company’s top model, listing for $329 – $50 more than the Stratocaster! Through its run, which ended in 1980, Fender offered all the same color options and hardware finish upgrades on the Jazzmaster. Still, fate didn’t see fit to favor the model, either in its prime or in the annals of guitar history, and today, prices on vintage Jazzmasters reflect the ongoing preference for the more revered, more heard “king” of Fender guitars – the Strat.

Here’s an abbreviated list of current values on the Jazzmaster, from The Official Vintage Guitar Price Guide 2004. And though they have, like most vintage solidbody electric guitars, proven a good investment, a ’58 Stratocaster, by comparison, today sells for three times the price of a ’58 Jazzmaster. Prices shown are for guitars in excellent condition (all original parts and finish, no playing wear, minimal weather checking).

| 1958 |

|

Sunburst |

|

$3,500 to $4,500 |

| 1958 |

|

Sunburst, maple fingerboard |

|

$5,000 to $6,000 |

| 1959 |

|

Olympic White |

|

$4,000 to $5,000 |

| 1959 |

|

Sonic Blue |

|

$4,500 to $5,800 |

| 1959 |

|

Sunburst |

|

$3,500 to $4,500 |

| 1960 |

|

Blond |

|

$4,300 to $5,300 |

| 1960 |

|

Olympic White |

|

$3,900 to $5,000 |

| 1960 |

|

Sunburst |

|

$3,000 to $4,000 |

| 1961 |

|

Blond |

|

$4,500 to $5,800 |

| 1961 |

|

Olympic White |

|

$3,800 to $5,000 |

| 1961 |

|

Shell Pink |

|

$5,200 to $6,700 |

| 1961 |

|

Sunburst |

|

$2,900 to $3,100 |

| 1962 |

|

Black, matching headstock |

|

$4,000 to $5,200 |

| 1962 |

|

Blond translucent over ash |

|

$4,200 to $5,700 |

| 1962 |

|

Burgundy Mist, slab board |

|

$5,000 to $6,500 |

| 1965 |

|

Natural |

|

$3,000 to $3,500 |

| 1965 |

|

Olympic White |

|

$3,000 to $3,500 |

| 1965 |

|

Sonic Blue |

|

$3,700 to $5,500 |

| 1965 |

|

Sunburst |

|

$1,800 to $2,300 |

| 1966 |

|

Candy Apple Red |

|

$2,900 to $3,500 |

| 1966 |

|

Dakota Red |

|

$3,500 to $5,000 |

| 1966 |

|

Ice Blue Metallic |

|

$3,500 to $5,000 |

| 1966 |

|

Lake Placid Blue |

|

$3,000 to $3,500 |

| 1966 |

|

Olympic White |

|

$2,900 to $3,400 |

| 1969 |

|

Sunburst |

|

$1,500 $2,000 |

| 1970-1972 |

|

Candy Apple Red |

|

$1,700 $2,000 |

| 1970-1972 |

|

Sunburst |

|

$1,300 $1,700 |

| 1973-1974 |

|

Natural |

|

$1,000 $1,400 |

| 1973-1974 |

|

Sunburst |

|

$1,200 $1,500 |

| 1975-1980 |

|

Sunburst |

|

$1,000 $1,400 |

This feature was first published in the May ’04 issue of Vintage Guitar magazine.