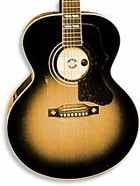

1960 Schulte Custom Doubleneck, courtesy of Eric Schulte.

You know the experience. You stop at your favorite music store, scan the axes hanging on the rack, and get a little whiplash as your eyes snap back toward a handsome beast you’ve not seen before. When this happens to me, more often than not it’s because I’ve just located another guitar made by Philadelphia-area luthier Eric Schulte.

Schulte’s forte, not unlike larger manufacturers (including Hamer, Dean, and most Japanese manufacturers active in the ’70s and ’80s), has been making very high-quality “interpretations” of classic American guitars. And since he’s made quite a few through the years, it’s entirely possible you’ll one day encounter a guitar with the Schulte logo. And when you do, you’ll know where it came from.

Malvern Roots

C. Eric Schulte was born August 28, 1923, in Malvern, Pennsylvania, just a hop, skip, and jump from where he lives today in a modest farmhouse in Frazer, Pennsylvania. Malvern was then a sleepy little town sitting atop a high hill above Great Valley, a fertile swath of farmland west of Valley Forge, on the far western fringe of Philadelphia. Malvern is best known as the site of the Paoli Massacre, a galvanizing Revolutionary War battle named for a nearby town – when British troops came up the hill out of Great Valley at night and killed several hundred sleeping American soldiers serving under General Anthony Wayne. This led to the failed attempt to recapture Philadelphia at the battle of Germantown, and Washington’s retreat into Valley Forge, the darkest days of the revolution. Malvern is still a sleepy little town, but much of the farmland has sprouted housing developments and Great Valley now is the site of Philly’s high-tech corridor.

Schulte became interested in guitars during the Great Depression. He recalls a new family moved in across the street, and two brothers and a nephew who used to play country music on the front porch. The brothers played guitar and harmonica, the nephew did mandolin and fiddle. Eric’s sister had a Stella guitar he borrowed, learned some chords on, and took over to front porch jam sessions across the street.

Schulte saw action during World War II in an engineering unit that participated in the invasion on D-Day on Omaha Beach. His unit was one of the first to cross the Rhine and enter Germany. He likes to reminisce about those experiences. It was during the war that Schulte first encountered motorcyles, which he, like many other guitarmakers (think Paul Bigsby), enjoyed working on.

Following the war, Schulte returned to Pennsylvania, got married, and took up a trade as an auto mechanic – ironically a “fender” man whose responsibility included painting the fenders he was repairing.

Decorating Guitars

Around 1950, Schulte became interested in doing more than just playing guitars. He recalls buying a couple Silvertone acoustic archtops from the Sears catalog. His first modification of an instrument was to add some binding to the sides and f-holes, using (what else?) paint.

A few of his friends saw the “improvements” and before long were bringing their guitars to be spruced up. From there, his involvement began to snowball, and it wasn’t long before strangers were coming to get the Schulte treatment.

From painted trim, it wasn’t a big step to try building guitars in the early ’50s. His very first was a pear-shaped solidbody. Schulte made the body and bought a neck from Carvin. He used Carvin necks for most of his early guitars.

As Schulte explains, when you make a guitar, you see how to improve what you’ve just done. So he’d begin another one, and the canon began to grow.

Fender Teles and Franchises

The majority of Schulte’s instruments are “copies” of popular American designs, a tradition he began in the mid ’50s. This was before Fender had really begun to penetrate the East Coast – there were probably half a dozen Telecasters in the region at the time. A buddy of his got one and Eric proceeded to make a copy. He showed his copy around and one fellow liked it so much he swapped Eric for a real one! Schulte kept that Tele for awhile and eventually traded it in to a dealer for a Gibson thinline. It was the first of many guitars he wishes he’d never gotten rid of!

Schulte soon began to get deeper into the guitar business. In the ’50s he began to acquire a number of musical instrument franchises, including Martin and Guild.

Ca. ’57, he applied for a Gibson franchise. At the time, Gibson dealers had to be at least nine miles apart, and there were two dealers within the limit. Gibson’s representative offered Schulte an Epiphone franchise, but he declined. Eventually, Gibson did make him a second-class dealer, which meant he could get Gibson parts and actually get Gibson guitars to sell only if no other local dealers were carrying the particular model. He remained a second-class Gibson dealer until the Norlin takeover in ’68, when the system was redone and dealership classification was eliminated.

The Schulte Custom

Most of Schulte’s ’50s guitars were steps on the road of learning, but by late ’57 he was confident enough to introduce his own design, the Schulte Custom. Because they are mostly built to order, he calls all his guitars “Schulte Custom,” but early on, the term referred to a specific model. Some of his guitars have a Schulte Custom logo, some just the Schulte logo. A few also have a pearl inlaid SC.

The Schulte Custom was a single-cutaway semi-hollowbody made of two pieces of solid wood – a front and a back

.jpg)