You’ve likely heard Stephen Bruton without knowing who he is. He has backed up luminaries like Kris Kristofferson and Bonnie Raitt, and appeared in numerous movies.

While Bruton was raised in Fort Worth, Texas, his experiences in his fledgling years weren’t ensconced in one musical genre, which paid off with his association with various other singers and players, as not only a guitarist, but also as a producer. When VG hooked up with Bruton, his fourth solo album had just been released and was garnering very positive reviews.

Vintage Guitar: It’s been reported that your “guitar epiphany” wasn’t seeing the Beatles on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” but a similar experience at a concert.

Stephen Bruton: Actually, I think there were two epiphanies. I went to a concert where my father was the drummer in one of the jazz groups. My mother asked if there was anything onstage that interested me, and I said, “Yeah,” and pointed to the guitar. It was something like a (Gibson) ES-175 being played by a guy named Charlie Pearson.

It looked cool, but one Saturday morning I went to my dad’s record store – I was about 10 at the time – and there were some kids there a few years older who were rehearsing for a talent show, playing folk music – Kingston Trio, Brothers Four stuff. It was the first time I heard someone singing and playing an acoustic guitar, and it just kind of shot through me. I thought it was like carrying a little piano around; you could play all kinds of music with it – jazz, folk. Suddenly, it all made sense.

And living in a record store, I could listen to all kinds of incredible play-ers – Segovia, Montoya, Tal Farlow, Howard Roberts, Joe Pass, a lot of rock and roll guys. The guitar was everywhere!

How long was it before you got a guitar?

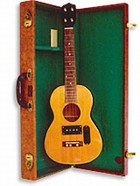

After a year of being good (chuckles), I got a Gibson LG-0 for Christ-mas. My dad got it for me because although it was the cheapest gui-tar Gibson made, it was still a quality instrument. If things hadn’t worked out, he still could’ve gotten his money back.

I took lessons for six months from Charlie Pearson. When he got drafted, my father told me, “You’ve got six months of lessons under your belt; you’re either serious about this or you’re not.” That’s when I started to play by ear. I started looking at chords and figuring out folks songs. And I started paying attention to players like Chuck Berry.

What was the Fort Worth musical environment like?

It was one of the most un-hip places in the world (chuckles). T-Bone Burnett and I talk about how it wasn’t a big musical center, but it was actually was! The reason so many great players came out of there was because it wasn’t a focal point. Milton Brown and the Brownies, the guys who started Western swing, came from Fort Worth. Bob Wills was playing in Milton’s band back then; the Light Crust Doughboys were around. Ornette Coleman, one of the greatest jazz sax players of all time, came out of that town, as did James Clay and “Fathead” Newman. T-Bone Walker came from around here, as did Cornell Dupree and Delbert McClinton. A lot of the original Texas Play-boys were from Fort Worth. Dean Parks, one of the A-list L.A. session players, went to school with T-Bone Burnett. All types of music – jazz, Broadway, blues, country, Western swing – were represented.

As a result, by the time I was playing with T-Bone or Delbert or my own band, the level of musicianship was very high, across the board. By junior high, I could tell a good blues player from a good country player, and I could tell a good fiddle player, drummer, or bass player. A lot of that had to do with listening to so much music in my dad’s record store and hanging out with mu-sicians.

And I really need to credit my brother, Sumter. He was an enormous influ-ence on me. When we were growing up, I got off into country and blue-grass, but he was a blues freak. He was four years older than me, and got me into Howling Wolf, Muddy Waters, and B.B. King. Between my dad and my brother, I got a lot of direction. My brother still lives in Fort Worth; he’s a fine guitar player and he runs my family’s record store there.

With all of those types of music to influence you, it must have been difficult to settle on a particular type of electric guitar.

My first electric was a hollowbody non-cutaway Gibson archtop with a single pickup, and I ran it through my dad’s hi-fi. I played Gibsons for a long time; my favorite players played Gibsons, and there was the perception that if you could afford a Gibson, you were hot stuff (chuck-les).

When I was in Woodstock, my roommate was Lindsay Holland, and he was working for the Band as an equipment manager and road manager. He bought a Telecaster in a pawn shop, and wasn’t getting any use out of it, so he gave it to me around the time I was going to work for Kristofferson. I loved it! Its neck pickup had that nice, round, warm Gibson sound, but I’m not a fan of that super-high-end treble pickup, but at the time, they were cheap.

That guitar was stolen, and Ronnie Hawkins gave me another Telecaster, when I was playing with him in Toronto; I’d played there with Kris, then I hung around and played with Ronnie.

Then I kind of took the attitude of “Jeez, I wonder what else is out there?” and I played everything from an Alembic to Les Pauls to Strato-casters to ES-350s to ES-5s. Then I finally ended up with another Tele-caster, and I said, “Wow, that was a big circle!”

But I noticed that the high-end sound I didn’t like was actually giving me some tinnitus. I started playing in a trio, and I liked a humbucking sound in that format. I’d picked up a couple of PRS guitars; Bonnie Lloyd was instrumental in making sure PRS guitars got played by real players. I like the way the wang bar was more flush, and I liked the push/pull pots so you can get a single-coil sound.

Then in ’93 I bought a ’60 (Gibson) ES-335, and about six years ago I bought a ’58 dot-neck 335 in sunburst, and it’s my favorite. Line ’em all up, and that’s the one I’ll pick.

Your association with Kristofferson was off-and-on for about 17 years, and you wrote songs together.

We started writing songs the first week I was with him; we wrote a song called “Border Lord,” which was the title track for his third album. I was with him for three years, then I left to go with Delbert McClinton and Glenn Clark, and I wound up spending a few years on the road with Geoff and Maria Muldaur, separately. I did her “Midnight At The Oasis” tour, then I did a bunch of dates with Geoff. He’s one of my favorite musicians; we’ve worked with each other for some 25 to 30 years, when-ever he needs me.

When I re-joined Kris, I did A Star is Born with him and Barbra Streisand. I worked on Lowell George’s first solo album, Steve Goodman’s album, and with Gene Clark. I was very fortunate to have been around all of those players and so many different styles. I did a fair amount of sessions and tried to learn from each.

What about your experiences with Bonnie Raitt?

Bonnie and I have known each other since my first year with Kris, when she opened a show for him; it was just her and (bass player) Freebo. She remembers the day; she was 20, I was 21. We were like two kids who had joined the circus. In ’93, I heard from her; she really liked the band I had with Glenn Clark, and asked us to be her primary guitar player and keyboard player. I did three world tours with her, and at the same time, I had the opportunity to make my first solo album.

By then, you’d also had some opportunities as a producer.

I produced Hal Ketchum, Jimmy Dale Gilmore, Sue Foley, Johnny Nicholas, Storyville, quite a few. People seemed to be interested in my studio sensibility; it was kind of a logical step to go from one side of the glass to the other. The payoff, for me, was not that I’d been an experi-enced sideman and studio player, but that I grew up in a record store, and I knew all kinds of music. I could quote from different things I’d heard in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. If they wanted something along the lines of a mid-’60s Dave Dudley sound, I knew what that was, and if they wanted something like Creed Taylor’s arrangements for Wes Montgomery, I knew about that, too!

Did you quit the road specifically to concentrate on your solo career?

Well, after I did my first record, I did a tour behind it, including some dates in Europe. The album was on a small label, and it was what I’d call “economy with dignity.”

I’d never thought of myself as a solo artist, because I was always in a band dynamic. But the band I’d been in had kind of broken up, so I decided to make a go of a solo career. With favorable reviews and some touring, I was able to make some more records… and I never thought I -would be talking with an interviewer to promote my fourth album (laughs)! It’s not been planned; it’s always along the lines of “what happens next.” I’ve been involved in other projects all along, but it has all dovetailed nicely.

The third album, Nothin’ But the Truth, only had one lead guitar break…

Not much take-off guitar (chuckles)! I just did what the song called for, at a very minimalistic level. But when New West Records asked me to make another record, they told me I had to play more guitar. So I did.

You’re based in Austin, but you recorded the new album, Spirit World, at a home studio in L.A.

We had a budget, and I started looking at the time constraints, and I realized that I’d get more bang for the buck if I went to one place and stayed there. And I could stay in Mark Goldenberg’s home studio a lot longer than if I went to a regular recording studio. Al-so, I could stay focused.

And that’s what happened. Instead of making a three-week album, we made a six-week album, and it sounds like there was more time and thought put into it; it doesn’t have a hurried quality to it.

I’ve always wanted to work with Mark, anyway. He’s a great, unique guitar player; he’d been in the Cretones – a band that did an album with Linda Ronstadt back in the ’70s. He doesn’t play any musical cliches, and he and I both occasionally take lessons from Ted Greene, in L.A. Ted is a melodic, chordal, theoretical genius. Mark is much more into music theory than I am, and it doesn’t look like we’d be on the same musical wavelength, but we are in a lot of ways. He has worked with Don Was, and he produced Natalie Imbruglia’s Left of the Middle album. What was gratifying for me was that on my new album, he didn’t try to change what I was trying to do; he would maximize the chances of it happening that way.

A lot of the tracks are relatively long; only one is less than 41/2 minutes. The lead-off song, “Yo Yo,” is seven minutes long, and while it has a whimsical title, it’s fairly serious, lyrically.

Well, it’s an acronym for “You’re on your own.” When the musicians on a Kristofferson tour would go their separate ways at the conclusion, we’d say “Yo Yo” to each other. I always thought it was a good idea for a song, because life is that way at times; you’re on your own a lot, and things can go up and down. I used one of Rick Turner’s Renaissance guitars on that song, and on a lot of the album.

What about the slide on songs like “Book of Dreams?”

Open G tuning. A guy named Larry Pogreba, in Montana, made a guitar I call “The Ugly Stick.” It has a Teisco pickup, and a mys-tery pickup.

I used all Dumble amps on the album, I really think they’re far ahead of any-thing else I’ve tried. On “Book of Dreams,” I plugged into a low-watt Dumble with four 10s, and the marriage between guitar and amp was great. All I had to do was find the sweet spot, which, for me, is very easy on a Dumble. That was done in about 11/2 takes; I think I re-did a portion of it.

How autobiographical is “Acre of Snakes?”

It’s about a time in a couple of bands when I was known as “the freak magnet” (chuckles). There were several people who thought I was subliminally communicating to them through my songs. Some were writing songs in answer to my songs. One person shook my hand at a gig and wouldn’t let go, claiming that a friend’s spirit was flying around me onstage while I was playing. I thought, “Check, please!”

I think that may happen to a lot of musicians, and it doesn’t have to happen on any kind of major level; you encounter people who are… in a parallel dimension (laughs).

Other instruments you played on the new album?

The ’58 335, a Paul Reed Smith, and a ’54 Telecaster that Mark has, which sounded incredible. Acoustic guitars were an early ’40s (Martin) mahogany 00-17, and an early ’40s Gibson banner J-45.

The cover photo looks like some sort of Native American ceremony.

That was taken in an interior town in Mexico; those natives have traced their lineage to a tribe or race that inhabited the city discovered beneath Mexico City when they were excavating for a new subway system. The photographer was a screenplay writer named Bill Wittliff; he did movies like The Perfect Storm, as well as the “Lonesome Dove” TV mini-series. But he also has a premier collection of Central and South American photographs; one of the largest in the world.

The dedication on the back to deceased individuals includes George Harrison.

I was driving to play a gig when I heard he’d passed away. He rep-resented more than himself, of course, but he was a genius guitar play-er because what he played for solos were as important as the lyrics. You find yourself singing the solos just like the words, because he did countermelodies; it wasn’t just a bunch of blues riffs or “lickster” stuff. It served the song.

What appealed to you about Grady Martin’s playing?

He was one of the best guitar players I ever heard, anywhere, anytime, and in any style. But he was primarily a jazz player. He was playing with Willie Nelson for awhile when I was with Kris, and we did a lot of shows together. I took him to see ZZ Top one time in Salt Lake City, and for him, it was one of the high-lights of the entire tour; he thought it was one of the coolest things he’d ever seen and heard.

And although somebody else got credit, Grady primarily produced Hank Garland’s Jazz Winds from a New Direction album; he and Hank were roommates at the time. Can you imagine back then, in Nashville’s heyday, when you called up for a session, the three guitar players you got were Grady Martin, Hank Garland, and Chet Atkins. And they’d pro-bably say things like, “Who wants to play rhythm, and who wants to play take-off?” (chuckles)!

John “Mambo” Treanor was a drummer from Austin.

He played with Robben Ford on the first tour Robben did under his own name. John was a remarkable drummer, and a colorful character. He loved straight-ahead jazz, and had huge chops in that style, but at the same time, he loved playing things like washboards. He played whatever served the song best.

And the same thing could be said for Champ Hood, who was a great fiddle player who wouldn’t call attention to himself. Champ was also a great guitar player.

Vernon White was Kristofferson’s manager, and was one of my very best friends… so in addition to 9/11, last year wasn’t a good year for me.

Some may hear a strong Dire Straits vibe at more than one juncture on Spirit World. Fair statement?

Well, I’m not real well-versed on that band; I think I’ve got a couple of those records, but Mark Knopfler is certainly a singular–sounding artist. He’s great. I think he and I both sort of “talk sing” the lyrics, and also, we both have little regard for four-minute songs that will fit onto the radio (chuckles). We just let the song unfold. With that in mind, I’m certainly honored to be considered in that type of peer group. He and I are probably about the same age.

What’s the pink Strat-like guitar in one of your publicity pictures?

It’s a parts guitar; the neck is a Warmoth that feels like a ’54 V-neck, and it’s been beat up enough to where it feels perfect. The pickups are a Teisco and an early ’60s Rickenbacker; the string-through–the-magnet type. I have some Rick Turner pickups that are made the same way, and I really like those, but this original Ricky sounds a little darker, which is what I wanted.

And as we’re recording this, you’ve been back in front of a camera recently, but it wasn’t for a video, as I understand it.

I was working with a friend of mine who’s a documentary filmmaker, and he’s making his first foray into commercial film. But I’ve been in a lot of movies, especially when I was with Kris. We always got included because he liked to have his band around. I had a good part in Song-writer; I got caught with Rip Torn’s wife (laughs). I still get small parts on occasion; I was a bartender in Miss Congeniality, and I was sing-ing a song in Michael. But my own music has priority these days.

Stephen Bruton’s songwriting and guitar abilities have made for a very listenable fourth album. Spirit World doesn’t overwhelm a listener in any way, but its clever licks and lyrics snag the ear of anyone interested in finely-crafted contemporary music.

Photo: MKB Photography, courtesy of New West records.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Sept. ’02 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

.jpg)