The garage behind Mark Sampson’s Southern California home is a Batcave for vintage tube amp lovers. Dark, dusty storage areas are crammed with ancient tan-colored Vox AC-10 “TV” models from the late ’50s, Super Beatles with chrome stands, original mint-condition Vox sales and promotion banners. There are also prototypes of the superb Matchless amps Sampson designed and assembled here on his work bench amid a clutter of electronic parts and pieces, wonky graying tube testers and oscilloscopes that look as if they were taken off a World War II battleship. The venerable old Vox and sleek new Matchless amps exist side-by-side, one informing the other.

Of course, Matchless has long outgrown Sampson’s garage. There’s a new factory in Pico Rivera. The product line has been expanded from the original DC-30 amps to a full range of heads, cabinets and combos of all sizes, and there’s also a series of heavy duty active pedals featuring analog-friendly 12AX7s.

Sampson’s journey began in another garage, amid the world of drag racers and street rods in his native Mason City, Iowa. He did 10 years as a professional drag racer on the local circuit, building and modifying street rods, competing in custom car shows. Much of his interest in design engineering was formed during this period.

“I worked in a shop where a guy could walk in with an idea in his head, and if he kept his bills current, nine months later drive it away,” he said.

Another influence was his father, a TV repairman and tinkerer who handed down the know-how to read a circuit and a voltage meter and, most importantly, a curiosity about how electronic things worked. Then, of course, there was the Beatles.

“I can remember a very detailed plywood collage I made when I was 12,” he remembers. “It showed the four of them standing on a stage complete with Rickenbacker guitars and Vox amps.”

As he labored in the street rod shop by day, Sampson played in rock bands by night. His parents were as much relieved as supportive of the music.

“I’d been racing dragsters for a living, so they saw this rock and roll band stuff as toned down.”

The band would gig, and the amps would inevitably break down. Sampson couldn’t find anyone to fix them, so he took on the repair tasks himself. “Playing in the band taught me everything. Equipment breaks down on the road, that’s the story of every band. I was the fix-it guy. I learned a lot about how things worked.”

As his band traveled, Sampson searched for the English Vox amps his heroes played, but there were none to be found in Mason City. “Nobody cared about amps back then. It was better to have a new, dependable amp.”

He started making trips around the music stores of the Midwest and finally found a few Voxes at a Minneapolis store called Knut-Koupeé. He was still custom painting cars and worked a trade for the Vox amps by painting guitar bodies for Knute.

One of the store’s more notable customers was Prince (back in the days when he had a name). Sampson painted two of the guitars used in the movie Purple Rain and ended up doing a lot of deals, trading his painting services for guitars and amps. He ranged further afield in his quest to locate British amps. James Werner, noted for his Fender serial number lists, put Sampson together with a trader in England Sampson describes as “…sort of the British inverse of me.” Soon, Fenders were being shipped to England and Voxes, Marshalls, and Hiwatts were coming to Iowa.

“I was exposed to the British side of design and manufacturing,” says Sampson. “I amassed a collection of sounds, just because I wanted to know. I had a curiosity about why something sounded the way it did. I did a lot of reverse engineering of those English amps. A lot of them were in various stages of disrepair, which kept the prices down. You could buy an AC-30 for the equivalent of about $225. There was no market for them. This was in the early ’80s. A plexi Marshall cost about the same. If you had a piece owned and documented by someone famous, it was worth more, but not much. I remember buying a bass rig off one of the guys from Badfinger. It was an AC-50 in a small cabinet with a 15″ and a 12″ bottom. It was only 50 lbs. over normal price. I wish I’d kept it.”

Sampson’s band was his testing ground. “But I was the only one interested in this English gear and it caused problems because, like any band, you’re trying to define yourself, your music and direction, and the other guys never knew where I was going. One week I’d show up with a Marshall half-stack and an SG Jr. The next week it’d be a Strat with a Bluesbreaker. I can understand now how frustrating it must’ve been for them, not knowing from week to week what I’d show up with or how I’d sound, but at the same time I wanted to know what these things were about. I tried to tell them, ‘Just don’t worry about me, I’ll come through. You take care of your deal and we’ll be fine.”‘

Listening with a critical ear to a variety of British amps, Sampson began to note the differences in sound design.

“There is a peculiar midrange thing all British amps do that American amps do not. And, of course, between British amps there are big differences. An AC-30 and a Marshall JTM-45 sound absolutely nothing alike when they’re clean or breaking up. But they both sound, in the midrange, unlike an American-made amp. Vox blue speakers don’t transfer the top-end like an American speaker does. They have a decided lack of bottom due to a lack of magnetic strength in the Alnico (compared to a ceramic), but a delightful, pleasing midrange. Celestion speakers are not as tight, and don’t carry the bottom end of American speakers. Having said that, the tweed Fender Bassman is almost the total exception to the midrange rule. Although the 10″ speakers tend not to have the midrange character a Celestion might have…to my ears.”

Sampson saw how cultural differences between Americans and Brits influenced their amp designs.

“Most design engineers agree that American stuff – and this goes for more than just amplifiers – tends to be overbuilt. Unless it’s on the very low end, it won’t break down. Whereas the British tend to make things a little finer, with nicer looks and detail, but with a trade-off in reliability. This could go for their car designs, as well. Anyone who loves Jaguars will see that.”

Early Marshall amps had perceived reliability questions among vintage filament heads. But Sampson’s experience has shown him old Marshalls can hold up fine if they are biased right and have the correct tubes.

“There was this perception, when the company switched from EL34s to sturdier but different-sounding 6550s, that quality control had suffered and the amps weren’t being built like they used to, and there might’ve even been some truth to that, as the company was expanding its market and wanted their export amps to avoid a rash of tube blowout problems. But it was simply a matter of re-biasing the amps to accommodate whichever tubes you wanted to use.”

Looking into the work of another esteemed amp builder, Hiwatt’s Dave Reeves, Sampson found Hiwatt’s solid-core wiring created its own problems. “I’ve seen them wiggle and break. I don’t like solid-core wire and Hiwatts use a lot of it. Granted, they are fixed very neatly in nice right angles. You can see Reeves’ military influence. And the amps sound good.”

But the sound and heritage of a Vox AC-30 was Sampson’s primary reference. He tracked down and bought all of Vox inventor Dick Denny’s original blueprints and schematic diagrams. He cultivated relationships with former Vox employees.

“I’ve got a 10-page letter from the lady who was Tom Jennings’ first employee. She worked with him from ’52 to ’62. Her story was just amazing. This is post-World War II England, there’s nothing left of the country, the buildings have all been blown up, the economy is crap. It’s a shambles. And it’s just her and Jennings.

“Jennings was a conservative man. He wasn’t so involved with the circuit design – that was Dick Denny’s. But he was very concerned with the company image, and what the product looked like. He was the one who painted Vox’s Celestion-made speakers blue just to distinguish them. And this lady was quite loyal to Jennings. He helped her family through tough times. He gave them food when there was no money. She stayed with him until the Beatles hit.”

From the Vox employee and other sources, Sampson built a database on the Vox company, logging serial numbers, transformer changes, production dates. He calculated how many units the company was building, about 100 a day by 1963. According to a best guess, Vox built somewhere around 20,000 amplifiers in the course of seven years.

“And they weren’t cheap, at least not for the working class and the average musician. It would’ve taken the average workman’s yearly wages to buy one,” Sampson said.

Sampson remembers going to buy a Vox Super Beatle in 1966, “…and it was about $1,300, the price of a Corvair. That was a fortune back then, so you’d only see those amps with rich kids and rock stars on TV which is, by the way, a great marketing ploy if you can pull it off. Here is this amp that is seriously expensive, that the stars are using, and you figure they can afford the best, so you really have to have something that hits a home run with them before they’ll consider using it. They just won’t use some schlocky piece of gear even if it’s free, because they don’t respect that, either. Having the name of your amp on TV being played by stars, that’s the best kind of advertising there is.”

While trading overseas, Sampson made his ultimate amp score right in his home town. “Carlton Stuart Music in Mason City was the store of my youth,” he said. “It was a place where mom and dad could come in and buy Junior a trumpet. I’d forgotten about this place when I started on my search of Vox and English amps. So I went in there and found a lady who understood what I was looking for. She pulled me aside and told me to come back on Saturday. I was intrigued. What? What are you gonna show me? She just said, ‘Come back Saturday.’

“I wasn’t sure what was going on. The owner of the store had passed away, and the store was in probate. I went back, and this lady takes me upstairs to the storage area. We go through a fire door. It felt like nobody had been up there in years. The lady starts talking about an older man who had died up here under strange circumstances. The fire department had to seal the area off. I’m listening to this, and I’m feeling just a little buggy. Then she slides open a door and I walk into a room filled wall-to-wall with original Vox instruments, amps and guitars and Continental organs with price tags hanging off them, still wrapped in plastic shipping cases. There were Beatles and Stones endorsement posters on the walls. The same vomity green shag carpeting from the ’70s. It was like the Twilight Zone!

“The store owner had literally shut the door to this room in 1972 and left all the instruments inside because Vox had gone bankrupt. I bought the whole inventory for $250 and the lady was happy to get the stuff out of there. I loaded the car as fast as I could. It took me three trips but they’d only let me in there to move the amps out on Saturdays, so it took me a month to carry it off!”

Sampson sold off most of his Carlton Stuart cache (Vox made some pretty awful guitars) and saved the amps to disembowel and sound out.

“The early Vox design was very similar to a Mullard-Osram valve company published circuit design for a power amp section,” he said. “Vox was designing circuits for organs, so they probably experimented with the Mullard design and their own preamp ideas. It was all influenced by available parts, suppliers, and vendors. An engineer might choose a part he can afford rather than the best one made, and that will affect everything else along the chain.”

He detected a construction problem in the AC-30’s plastic input jacks and saw the amp’s lack of ventilation as a serious problem regarding the component longevity.

That said, there’s a positive aspect to the heat generated by Class A amps.

“Those EL84 tubes lose power when they’re not real hot. An AC-30 will typically get a bit louder as the night goes on. Same with a Matchless. We tried a fan on some of the early amps, but it didn’t work very well. In fact, the amps lost power. It got down to about 25 watts by the end of the night. The amps without fans went up to 40 or 42 watts of clean power. We’ve been railed on by a number of our competitors about this issue, and it’s not an accident that we let the our amps run hot.

“I did a lot of homework on this issue, testing different brands of tubes with various rectifiers, plate voltages, different cabinet settings (head or combo). And every time it produced the same results. I came to the conclusion the cathode in the tube has to run at a certain temperature, and lacking the extremely expensive instrument to measure the temperature of the cathode, I accepted the fact that, because it was cooling too efficiently, it was cooling off the cathode and producing an electronic emission inside the tube and affecting the tube’s performance.”

Sampson’s amp import/export business blossomed in the mid ’80s as old tube amps slowly caught the wave of the vintage guitar market. He remembers his business back then as something of a frenzy. “I was driving to airports 100 miles away, dealing with customs, freight payments, paperwork. It was a big headache to get these British amps into the country. Nowadays it’s easy. You call up a freight shipping service and it’s done for you. But where I was, I had to do it all myself.”

He created mailing lists for his gear and started attending vintage guitar shows.

“At the time there were only three or four a year, and you’d see the same people at each show. I sold guitars, amps, T-shirts, anything – just kind of a traveling salesman.”

Eventually the business grew and had a few employees boxing and shipping amps while Sampson focused on finding them and bringing them back to good working order.

“At the time I quit bringing them in an AC-30 could be found for $800 for a clean one. Then the price doubled and leveled off to where it is now, around $1,400 to $1,800 for an average one, with the extremely clean stuff always getting a premium.”

Networking the vintage guitar circuit, Sampson expanded his contacts and developed a rep as the “go to” guy for all things Vox. John Jorgenson, then guitarist for the Desert Rose band and now a member of the Hellecasters and Elton John’s touring band, played and toured with AC-30s and called up Sampson looking for Vox parts.

“John had a lot of amps that were broken,” recalls Sampson. “He asked how much I would charge to go to California and repair them. We hit it off. He showed me the work that had been done on his amps, and it wasn’t very good. So I started making trips out to the West Coast to re-engineer some of the modifications. Then I met a producer named Jack Joseph Puig. He also started flying me out to L.A. He had an entourage of people living at his house, all of them famous musicians with broken amps. I worked a lot of hours with Jack.”

Jorgenson’s amps were breaking down so often, Sampson would sometimes fix them over the phone.

“I taught John how to read a meter and run a soldering gun,” says Sampson. “I put a little spare parts kit together for him. He’d call me from a hotel room on the road and he’d have the meter on, and we’d sort of walk through the amp and diagnose the problem via long distance.

It got to the point where I was making more money flying out here and doing repairs for John and Jack and their friends than I was buying, selling and trading. I started to study the amp market from a retail perspective, and I saw a giant void because, in the late ’80s, the only amplifier work being done was in modifying Marshalls. Rivera, Soldano, and Boogie. They were hot-rodding, not restoring. A good-sounding, roadworthy, clean amp was not being done.”

Seeing there was more opportunity on the West Coast, Sampson and his wife made the move to Los Angeles. He stayed solvent troubleshooting amps, often in studio situations where the guitarists weren’t getting the sound they wanted.

“Typically the producer and engineer would hire me,” says Sampson. “I’d come in, listen to the playbacks, talk to the guitarist to see what he’s going for. Then I’d start working on his setup and sound by re-tubing his amp, or change the speakers or mic the amp differently.”

Sampson found himself in some decidedly Spinal Tappish moments.

“I remember getting a call at two in the morning. I’m sound asleep. ‘You’ve gotta come down here’, this guy says. We’ve been here for 14 hours trying to get a sound.’ This is a high-profile artist, producer, and engineer. It’s the most expensive room in town. High visibility, groupies, hangers-on, the whole scene. I come down into Hollywood from my house, a 45-minute drive. I’m charging $100 an hour, two-hour minimum, cash only. I get there and they have this horrible rack, horrible cords, noise everywhere, a total mess. I unplugged everything. I plugged the guitar into the two AC-30s the guitarist was using in stereo. One sounded fine, the other sounded small and thin. I went over to this second amp and turned up the treble and bass. The guitarist hits a chord and shouts out in perfect Nigel Tufnel Britspeak, ‘That’s it! He’s gawt it!’ The engineer says, ‘Oh, so you have to fuss with the tone controls a bit, eh?’ We plug the racks back in and all is well. They spent 14 hours at $200 an hour, plus the engineer and second engineer, plus the producer’s time…to find out that a tone control had to be turned. Here I am, thinking, ‘Why is this guy making four times what I’m making, and he’s a star and I’m a nobody!”‘

Soon after arriving in L.A., local trading acquaintance Albert Molinaro introduced Sampson to Rick Perrotta, who had a similar background in engineering and business. Perrotta had just sold his interest in a recording studio and was looking for something to do. He and Sampson got together one night.

“We just decided we’d try to make some amps,” says Sampson. “It was simple, noncommittally. Just a, ‘Let’s have some fun’ kinda thing.”

Their initial idea was to create an amp based on the sonic principles of an AC-30, but more reliable and roadworthy. Like the Vox, it would feature a Class A circuit and a quartet of EL84 tubes in a 2 X 12 combo. But it would also boast a structural integrity unlike anything else on the market. From the complaints he’d heard on his studio-repair rounds, Sampson detected a desire for an amp that, “You could just plug in and play without the hassles of a vintage piece – but with that familiar sound.”

He evolved a design that would require only the best parts and would be expensive, but having dealt with the top echelon of Los Angeles studio players, Sampson believed his dream amp would appeal to pros who had to depend on their gear and could afford the best.

“The market actually tells the manufacturer what it wants,” he said. “Of course we didn’t know this at the time. We were just going on instinct. Looking back, I can see the vintage market in Fenders, Voxes, and Marshalls actually redefined what a guitar amplifier should be. We had, in the ’50s and early ’60s, the creations and innovations of Leo Fender, Dick Denny, and Jim Marshall, then a technological progression into the ’70s with channel switching and the hot-rodding of gain stages in the Boogies and Riveras, and then in the mid ’80s a desire to return to the sounds of the earlier designs – driven by the music we loved – which gave birth to the vintage and reissue markets.”

In looking for a name for their amp, Sampson and Perrotta searched out books, encyclopedias, lists of old trains, planes, and cars. Nothing stuck. “It was very frustrating,” Sampson remembers. “The circuit design was easy compared to getting the right name.” Then a friend of Sampson’s from Minnesota called with some ideas, one of which was Matchless, the name of an old British motorcycle. “We knew it when he heard it. It’s British, it means ‘no equal.’ That was us…we hoped.”

From his car building background, Sampson was familiar with banging out and bending sheet metal for the chassis. In his garage he’d cut holes in the metal, mount parts and start the wiring. Then the unit would go to Perrotta’s house to finish the wiring, install more components, and detail the cabinet. Then the unit would come back to Sampson’s garage to have the chassis installed in the cabinet, the speakers mounted, speaker wires run, and then the hardest part – picking the tubes.

“I would spend hours on the tubes,” said Sampson. “I’d take 30 preamp tubes and listen to each one in every location until I found the ultimate, best-sounding combination for that amp. The first 300-400 DC-30 amps were made that way.

“We wanted the original Blue speakers Celestion had made for Vox, but at the time Celestion told us there was absolutely no way they were going to make them again. The speakers were too expensive, and they’d lost the tooling for the Alnico magnet. Cobalt had become extremely expensive and difficult to obtain. So we started tailoring the Matchless amp to sound right for the speakers we could get. We wanted to stick with Celestions because their sound was closest to the sound of the Vox Blues. We did a lot of listening, wiring up two 25-watt speakers, a 25 and a 30, two 30s, linking them in series, in parallel, every conceivable combination you could imagine.

“We decided to use a combination of a 25 and a 30 because the two speakers did different things. It was a radical idea, but it sounded right. The 25-watt was smoother, and it sounded very good in the low midrange. The 30-watt had less of a midrange but an accented lower end and a better top end than the 25-watt. It was my decision and I went with one of each. Then we modified the speaker cones somewhat in an attempt to get them to sound like old speakers. By the time Celestion decided to reissue the original Blues, we had something we liked better. When the Blue speakers finally did come back (in the Korg reissue AC-30), I was sent a pair of engineering samples. We put them in a 2 X 12 extension cabinet alongside a pair of original Blues I had, with a pair of custom Matchless speakers in a third cabinet. Then we put all three cabinets through a Vox head and a Matchless head. We A/B’d everything, and it turned out the Vox speakers sounded best with the Vox head, and the Matchless speakers sounded best with the Matchless head.”

Between prototypes they made a conscious decision to veer away from a Vox look.

“There were obviously marketing considerations. And we didn’t want to get sued. Our intention had always been to go after the JMI Vox sound and feel, not necessarily the look and layout. And our amp was different in terms of the construction of the transformer, speaker configuration, number of channels and what they did. We also had a hi/low power switch, an effects loop, a master volume, and a couple of other electronic gizmos the AC-30 didn’t. So we made sure we altered the amp’s cosmetics, gave it a single handle instead of the three a Vox AC-30 had, and generally tried to avoid the comparison rather than invite it,” says Sampson.

Jorgenson took the second and third Matchless prototypes out on the road for a year, along with his AC-30s.

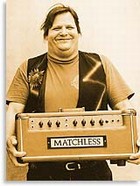

“We had to repair John’s Vox probably six to eight times in that year, and the Matchless never failed. The next amp we made was a head and cabinet, and it was for studio guitarist Mike Landau (VG interview, October ’97). It was made the same way as the first batch, sort of stuck together by Rick and I in our houses. I made the logo by cutting out a piece of clear plastic and using some stick-it letters, reversing them on masking tape and spray painting…it was like an arts-and-crafts project! At some point Landau brought it back for some kind of fix-up, and we thought it looked too hand-fashioned, too unprofessional. So we gave him a new one. I kept that first head and cabinet.”

Around this time Steve Goodale, a marketing guy who was also hanging around the vintage guitar shows, saw what Sampson and Perrotta were doing with their amp prototypes. He begged to join them. Unsure of what role he might play, but in dire need of money for parts, Sampson and Perrotta tested Goodale’s enthusiasm by charging him $20,000 to become a partner, assuming it would scare him off. Goodale kicked in the money.

“Steve’s big contribution was a knack for getting free publicity,” says Sampson. “Which Rick and I weren’t knowledgeable about. Steve was a bloodhound, always finding an angle, getting press attention, photos in magazines. He became the sales and marketing guy, Rick handled the business and I concentrated on design. That’s how we divided the duties.”

With Steve aboard, Sampson and Perrotta continued refining. Sampson laughingly recalls having a brainstorm one afternoon driving home from Rick’s house, “We’ll light up the logo!” They did a cut and paste job on the prototype that went on the road with John Jorgenson. Then Jorgenson found himself playing on a TV show called “Hot Country Nights,” and the Matchless team was able to see their creation on national television. They realized the marketing value in the lit up logo, that it would stand out from the normal backline of amps. More free publicity.

During a gig designing a recording studio, Perrotta met a talented carpenter named Kyle Kaiser, and hired him to build a cabinet. Soon, Kyle had his own cabinet-making shop with Matchless as his only client.

The team then went to local dealers, trying to interest them in the new amp. Fred Walecki, from Westwood Music, had heard about Matchless from Jackson Browne, who had heard about it from John Jorgenson.

“Fred called us and bought a couple amps and gave us a deposit for two more,” Sampson relates. “He was our first dealer. We were elated at his involvement because he has a high-end pro clientele – exactly the musicians we hoped to reach. Also, we needed a boost. We’d invested a lot of our own money in this venture and it was just sort of limping along. We didn’t have much to show for all of our work.”

The shootout changed all that.

Goodale learned Guitar Player magazine was conducting its first major evaluation of tube combo amps. The deadline for entering an amp in the comparison tests was only days away.

“Steve told me I had to get an amp done in four days to send to the magazine,” says Sampson. “At that time it was taking us two weeks to do each unit. I was still living off repairing other people’s amps. Rick was working part-time in a studio. We both had to drop what we were doing and work on nothing but this one amp. The pressure was crazy. Steve was yelling at us to finish by the deadline. But I wasn’t satisfied with the sound. I wanted it to be as good as it could possibly be, and it wasn’t there yet. I was saying to Steve, ‘We’re gonna get creamed. We’re nobody, we don’t know anything about what we’re doing.’ We were also the most expensive amp on the market, other than a Dumble, which you just couldn’t get. We viewed ourselves as these tiny little Davids with giant Goliaths out there. Honestly, the best I hoped for was a picture in the magazine. And that they wouldn’t say anything bad.”

They finished the gray-tolex DC-30 just in time, and Perrotta drove it to the site in San Mateo. They promptly forgot about it.

“New Year’s Eve, 1991,” Sampson remembers. “We got a call from Gerald Weber, of Kendrick, congratulating us on winning the shootout. We were honestly floored. We really weren’t expecting anything like that. And we had absolutely no idea what kind of power and influence the article would carry. But the magazine with the shootout results wasn’t going to be on newsstands for another couple of months, so we knew we had this rave review but nobody else knew it. Which still left us hustling from one amp to the next.

“The shootout article hit the stands and within 90 days we had 65 dealers, all with valid orders and 50 percent deposits,” he said. ” The dealers funded our venture. Everything turned around fast. In fact it happened too fast. Here we were, coming from the struggle to get money coming in, to struggling to fill all of the new orders we had! Everybody wanted their amps and we were still building them in our houses, one at a time.

“It’s basically been a rags-to-riches story, like out of a film. But it worked because we worked real hard. We kept our collective nose to the grindstone. Personally, I would’ve kept going regardless of what happened. If Rick and Steve had wanted to give up, I would’ve continued. I just don’t give up when I sink my teeth into something. I never give up – until I’m ready to.”

Clay Frohman is a writer of films and television, based in Los Angeles. In addition to creating the screenplays for Under Fire and The Court Martial of Jackie Rob-inson, he is a guitarist for the Rockinghams, a gang of innovative roots-rockers gigging around the Southland.

Mark Sampson holding a Matchless prototype built for guitarist Michael Landau.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Aug. ’98 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.