This month we wrap up our saga of the Alamo by picking up with the new guitar line offered in 1965.

Alamo, as you recall, was originally set up by Southland Music and Charles Eilenberg after World War II (ca. 1947), making record players and battery-powered radios. Music instrument cases followed, and about 1949 or ?0, Alamo began making amplifiers and lap steels. In about 1960, Alamo branched out into solidbody electric Spanish guitars, with the Texan.

This began a long period of name and design shuffling, including the introduction of the hollow-core Titan, in 1963. Throughout the history of Alamo, the hollow-core and solidbodies would weave in and out of the story. Early Alamo guitars sported a variety of three-and-three/two-and-two headstocks, which brings us up to 1965…

Maximum Guitars

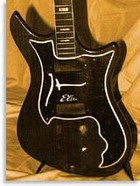

The real news for ?5 was an expanded line of electric Spanish guitars. Again, we can? be sure that some didn? appear earlier, but given the radical ?ow?designs and the hyperbole in the catalog copy, I suspect these were mostly a complete overhaul in ?5. The sort of frumpy shape of the Fiesta gave way to variation on a groovy hybrid between a Strat and a Jazzmaster, with double cutaway horns, sort of squashed outwards.

The center-humped headstock gave way to 4-in-line/6-in-line headstocks with a sort of squared-off Strat styling. Now standard fare was the more-or-less Strat-shaped pickguard, with slightly more refined squiggles than on the previous fetal pickguard. In the middle of these guards was a mysterious design consisting of a long slash on the bass side and under it a crooked, stylized lowercase ?.? This looks like it could be an Oriental character. However, on later models, the name of the guitar was also engraved on the guard and clearly, this was meant to be read straight on with the guitar standing upright. Also, it appears on other models, so it doesn? stand for Titan. The design thus became a stylized ?,?for Alamo.

In ?5, Alamo basically divided its guitars and basses into three groups; the Professional Line, the Artist Line and the Fiestas.

The ?5 Professionals included the Titan bass, the Eldorado bass and the Eldorado guitar. The Titan bass ($159.50) continued to have a hollow-core construction. The body was the squashed Strat with a lower horn slightly thicker than the Eldorados. The 20-fret fingerboard was rosewood with dots. A white pickguard had the stylized Oriental ??cutout, a single middle pickup and volume and tone controls. The bridge/tailpiece assembly was covered in chrome. The Titan bass that year came in three finishes: Model 2593 in sunburst, Model 2594 in blond, and Model 2597 in cherry.

The Eldorado guitar and bass were both solidbodies, with Honduran mahogany bodies. These looked very similar to the Titan, except the lower horn was thinner. On the Eldorado bass ($199.50), the pickguard was slightly larger and more squiggly than the Titan, black/white with an engraved Oriental ?? The 20-fret rosewood fingerboard was bound. This came in only one version, the Model 2600 in red cherry.

The Eldorado guitar was very similar to the bass, except it had two pickups, 3-way toggle, two volumes and two tones, and a bound rosewood fingerboard with block inlays! The Model 2598 ($159.50) was a stoptail in red cherry. The Model 2598T ($219.50) came outfitted with an original Bigsby vibrato.

The ?5 Artist Line included our old friends, the Titan Mark I and Mark II. These were now hollow-core guitars with the squashed Strat shape of the Titan bass, with a slightly thicker, squarish lower horn and smaller, less squiggly, Oriental ??pickguard in white or black, depending on the guitar color.

The Titan Mark I had a single pickup, which was finally moved back to the bridge position from the previous middle spot. The 20-fret Rosewood boards weren? bound, but they did have block inlays. The Mark I had volume and tone and the old rhythm/lead switch just in front of the volume knob. The Model 2589 was a stoptail in sunburst ($99.95), available as the Model 2589T with Bigsby ($159.95). The Model 2590 was blond, the Model 2590T had a Bigsby. The Model 2595 came in cherry, with the Model 2595T sporting a Bigsby. The Bigsby guitars all had adjustable metal compensated bridges, probably provided by Bigsby. The Titan Mark II added a neck pickup and a 3-way select by the lower horn (no rhythm/lead toggle). The Model 2591 ($119.95) came in sunburst, with the Model 2591T Bigsby option ($179.95). The Model 2592 came in blond (Model 2592T with Bigsby). The Model 2596 came in cherry (Model 2592T with Bigsby).

Finally, the ?5 line offered three Fiestas, with hollow-core bodies and an even more radically squashed Strat/Jazzmaster body. Sort of Strat road kill. These each had slightly different pickguard shapes depending on how many pickups, each without the Oriental ?? but with a cutout Fiesta just below the strings. The 19-fret Rosewood fingerboards were dot-inlaid. The six-in-line heads had small Alamo truss rod covers. These had uncovered Acra-Tune bridge/tailpiece assemblies, with no Bigsby option. The one-pickup Fiesta had the pickup near the bridge, with volume and tone. The Model 2584R ($64.95) came in red, the Model 2584W in white, the Model 2584S in sunburst, and Model 2584C in cherry sunburst. The 2-pickup Fiesta had volume and tone with a 3-way toggle near the lower horn. The Model 2586R ($84.95) came in red, the Model 2586W in white, the Model 2586S in sunburst, and the Model 2586C in cherry sunburst. The three-pickup Fiesta featured the pickups in parallel, with one volume and two tones, and three small plastic sliding on/off switches near the lower horn. The Model 2587R ($109.95) came in red, the Model 2587W in white, the Model 2587S in sunburst, and the Model 2587C in cherry sunburst.

Curiously enough, in the same Bruno catalog that featured the Alamo catalog, the old double-cutaway Alamo Titan Electric bass was also still offered. This was the older version with a hollow-core body, Strat-style pickguard, and the old curved-top 2-and-2 headstock. This was still available as the No. 2593 in sunburst, No. 2594 in blond, and No. 2597 in cherry, at $159.50. These, and the recycled Paragon amps for accordions and bass fiddles, were probably leftover, slightly older designs.

Summer O?Love

No picture is available of Alamos in 1966, but by 1967 the line had again undergone a fairly radical transformation, here with a catalog graciously provided by Scott Freilich of Top Shelf Music, Buffalo.

Alamo amplifiers in ?7 received yet another facelift, although not too drastic, when compared to the amps of two years earlier. They are still basically rectangular cabinets covered in black vinyl, but now with a darker black and silver grillcloth. Controls are now all face-mounted and the knobs sit on brushed aluminum plates. They are, however, tube amps, despite the very ?tandel?look. Gone is the little logo plate, in favor of a white plastic script Alamo lightning bolt perched at an angle on the upper left hand corner of the grill. Alamo divided its amps into four lines, the PA Series, Professional Series, Artist Series and Studio Series. For an extra $20, you could get optional castors.

The PA Series included four amps. Three were old friends, the piggybacks. The Model 2578 was the Super Band Piggy-Back (eight tubes, two channels, tremolo, two 12″ speakers, 35 watts/70 watts peak, $394.50), available, as before, in a Lansing option as the Model 2578JL12 ($694.50). The Model 2576 was the Band Piggy-Back (eight tubes, two channels, tremolo, 15″ speaker, 35 watts/70 watts peak, $354.50), Lansing option Model 2576JL15 ($504.50). The Model 2571 was the Galaxie, mistakenly identified in the text as a Piggy-Back, but clearly still a combo (seven tubes, two channels, tremolo, two 12″ speakers, 22 watts/44 watts peak, $249.50), Lansing option Model 2571JL12 ($384.50). New in ?7 was the Alamo Pro Reverb Piggy-Back amplifier Model 2579. This had eight tubes, two channels, tremolo, reverb, two 12″ speakers, 35 watts (70 watts peak), and cost $414.50 (no Lansing option).

The ?7 Alamo Professional Series consisted of three old friends and one new face. Still around was the Model 2575 Piggy-Back Bass amp (six tubes, two channels, 15″ speaker, 35 watts/70 watts peak, $334.50), Lansing option Model 2575JL15 ($484.50). Also still pumping was the Model 2569 Paragon Bass combo (six tubes, two channels, 15″ speaker, 35 watts/70 watts peak, $284.50), Lansing option Model 2569JL15 ($434.50).

Also remaining was the Model 2567 Futura with Reverb and Tremolo (eight tubes, two channels, 12″ speaker, 15 watts/30 watts peak, $199.50). New was the Model 2566 Fury Bass combo amp, with five tubes, three inputs, volume and two tones, 15″ Jensen speaker, 20 watts output (40 watts peak), and a $179.50 price tag.

The ?7 Alamo Artist Series was basically familiar amps with the new look. Included were the Model 2570 Electra Twin Ten, Model 2564 Jet, Model 2565 Montclair, and Model 2572 Titan, all with the same specs and pretty much the same prices. Also included ?with the new look ?was the Model 2574 Alamo Reverb Unit.

Finally, the ?7 Studio Series consisted mainly of a repackaging of other Alamo standbys, including the Model 2563 Embassy Tremolo, Model 2562 Challenger, and Model 2560 Capri, again the same except for the new cosmetics. One new amp joined the line, the Model 2573 Dart Tremolo, with four tubes, three inputs, tremolo with speed control, volume, tone, 10″ speaker, 3 watts/6 watts peak power, and a cost of $47.50.

Fiesta Siesta

Gone by ?7 was the time-honored Fiesta amplifier (and, for the time being, anyway, Fiesta guitars).

Curiously enough, Alamo also offered the No. 2599 Q-T Practice Aid, a solidstate little box which served as a practice amp with a set of headphones ($46.50).

All amps had an optional cover. At least six different extension speaker cabinets were also available for various models. Aloha.

Still hanging on in the ?7 line was the Model 2493 Embassy Hawaiian guitar, with the tapered triangular body, finished in Alpine White, with the black and red aluminum fingerboard.

Guitar Redux

Again in ?7, the Alamo guitar line was redefined, although it still reflected the ?5 look. Basically there were two groupings, the Professional Series and Fury guitars.

The ?7 Professional Series consisted of one guitar and one bass. The guitar was the Model 2598 Toronado solidbody. This was a slightly more conservative interpretation of the offset double cutaway Strat, with more pointed horns. The pickguard was still the squiggly Strat-style with the engraved Oriental ?? The head was a slightly truncated Strat-style 6-in-line, with more rounded features than its more angular predecessors. The elongated truss rod cover remained. This had a Honduran Mahogany body finished in red cherry. The bolt-on neck had a 20-fret Rosewood fingerboard with dots. It had two pickups, two volumes, two tones, and 3-way toggle near the lower horn. The Model 2598 cost $145 with the covered Acra-Tune bridge assembly. The Model 2598T came equipped with a Bigsby and adjustable compensated bridge for $199.50.

The bass was our old friend, the Model 2593 Titan. This remained a hollow core beast, but now with a goofy, more angular offset double-cutaway body profile, with the upper horn a large hump with an angle. It had one pickup and the Oriental ??pickguard. The head was the more rounded version like the Toronado. It came in sunburst and cost $145.

The Fury series ?not wanting to make things too easy for us ?included both hollow-core and solidbody guitars, all called Fury, which were engraved in script down under the strings! These all had the shorter, more rounded Strat-style heads, with the by now typical elongated truss rod cover. Fingerboards were all Rosewood with dots. The pickguards were identical to the previous, now defunct, Fiesta guitars. These were, for Alamo, fairly normal looking, aping fairly closely a Fender Jazzmaster shape.

The hollow-core Furies were called ??Hole Guitars because, as you might guess, they included, for the first time, a single f-hole on the lower bass bout. The Fury Standard was a stoptail axe with the Acra-Tune bridge assembly. This came with either one bridge pickup (Model 2583, $59.50) or with two pickups (Model 2585, with four controls and 3-way near the lower horn, $77.50). These could be had in sunburst or cherry sunburst.

The hollow Fury Tremolo was the same, except for the addition of a vibrato. This appeared to be a Japanese-made affair with a Bigsby-style spring. However, it doesn? look like most Japanese units, so it may indeed have been made for Alamo. The Model 2583T-SB (one pickup, sunburst) and Model 2583T-C (cherry sunburst) cost $74.50. The Model 2585T-SB (two pickups, sunburst) and Model 2585T-C (cherry sunburst) cost $92.50.

The solidbody Furies basically followed an identical pattern, except, of course, with no f-holes, but as Standards and Tremolos, with single or double pickups and sunburst or cherry sunburst finishes. The Model 2584 Fury Standard (one pickup) cost $59.50, while the Model 2586 Fury Standard (two pickups) cost $77.50. The Model 2584T Fury Tremolo (one pickup) cost $74.50, whereas the Model 2586T Fury Tremolo (two pickups) cost $92.50.

It should be noted that while the Fiesta guitar officially dropped from sight by the 1965 catalog, as can be seen in the example here, at least some Fiestas continued to be made in this later, more conservative style. Either the model was revived or, more likely, just continued to be made and not promoted. It is possible the Fiesta came back to life after the ?7 catalog, or, for that matter, just before this same guitar became the Fury. Until more catalogs materialize, this will probably just have to remain a mystery. Let us know if you have any catalogs you can loan to clarify this point.

Finally, in what seems to be the most quixotic moment in the Alamo story, Alamo offered a guitar kit in 1967, so you could build your own! The was the Custom Electric Guitar Kit #0010 and Kit #0010-D, with either one or two pickups, respectively. These were basically the new hollow Fury Tremolo, with the main difference being that pickups were slanted at an angle from bass to treble, neck to bridge. These were available from Spanish Guitars Ltd. in San Antonio, and came with all the parts and instructions for building your very own Alamo!

In any case, that just about does it for Alamo guitars. No reference materials are available after ?7, but everything we?e described so far pretty much covers the Alamos I?e seen (and since I?e seen Clark McAvoy? huge collection, I?e seen quite a few!). Don? be surprised (and be sure to let us know) if we?e missed something. It? not terribly likely that Alamo continued to put the energy into electric guitars much beyond this ?7 line. As we?e noted in the past, the market for beginner guitars pretty much went bust in 1968. Many Japanese companies went bankrupt, and our own venerable Valco, which had just purchased the Kay company, bit the dust, too. According to Mr. Eilenberg, Alamo guitars probably lasted until 1970 before going the way of all flesh. Or wood.

Valco/Kay

One final note, however. Eilenberg recalls traveling to Chicago for the Valco/Kay auction in 1969, a year after the company went bankrupt. He returned with several carloads of parts, including machine heads and fingerboards, which eventually went onto later Alamo guitars. Thus, if you find a late-era Alamo with Kay or Valco parts on it, it just may be kosher.

Southland Music also purchased a number of completed Kay guitars left over from the Valco hegemony, and these were ?lown out?at bargain basement prices in ?9.

Happy Days

Alamo guitars were hardly ever contenders in the big-time guitar stakes, although as the picture of the rhythm and blues outfit illustrates, Alamo did have its advocates! Perhaps the crowning achievement, however, was the appearance of an Alamo guitar in the hands of Richie on the television sitcom ?appy Days.?

Amps Away

However, the Alamo story did not end with its guitars. Amps continued to be made in San Antonio into the 1980s! As we?e seen, Alamo switched over to black vinyl coverings in the late ?0s, one of the early companies to adopt what would become almost universal practice.

Black Vinyl (late ?0s)

We can see the further evolution in the black vinyl-covered Alamo amplifier line illustrated in an undated brochure that appears to by very late ?0s or early ?0s. These were still all-tube amps at this time, very similar to those seen in ?7.

Alamo amps consisted of three ?ineups:?the Pro Line-Up, the Standard Line-Up, and the One-Niters. These were all basically rectangular cabinets with black mar-resistant vinyl covering and black and silver grillcloths, and white beading around the grill. Control panels, now in black were located on front. Logos were white script Alamos at an angle in the upper left corner of the grill. Many of the names should be familiar by now, though the details have again changed.

The Alamo Pro Line-Up consisted of two guitar amps ?or the lead player,?two bass amps, and a PA system. Guitar amps were led by the 2567 Futura Tremolo Reverb. This had two 12″ speakers, two channels, tremolo speed and intensity controls, reverb, and 45 watts RMS output. The 2571 Galaxie Twin-Ten Tremolo Reverb had one channel with volume, bass and treble controls, tremolo speed and intensity, reverb and 25 watts RMS output.

Bass-wise, the 2575CW Paragon Bass was a piggyback. The head offered two channels, four inputs, volume, bass, treble and 40 watts RMS output. The cabinet carried a 15″ speaker and an acoustically-lined speaker enclosure. The 2566 Fury Bass amp was a one-channel combo unit with volume, bass, treble, 15″ speaker and 30 watts RMS output.

The PA 200 system was driven by the PA200 Centurion, with four channels, eight inputs, with volume, bass, treble and reverb controls on each channel plus a master set. This pumped out 100 watts RMS, mixing the sound into two speaker cabinets, each with twin 12″ speakers.

The Alamo Standard Amplifier Line-Up featured six combo amps. Top of the line was the 2570 Twin-Ten with two channels, four inputs, volume and tone controls on each channel, tremolo with speed and intensity controls, two 10″ speakers and 20 watts RMS output. The 2563 Embassy had a single channel, volume, tone, tremolo with speed and intensity, a 10″ speaker and 10 watts RMS output. The 2562 Challenger had two inputs, volume, tone, no tremolo, 10″ speaker and 10 watts RMS output. The 2573 Dart had two inputs, volume, tone, tremolo with speed and intensity, an 8″ speaker and 5.5 watts RMS output. The 2560 Capri had two inputs, volume, tone, 8″ speaker and 5.5 watts RMS output. Rounding out the line was the 2525 Special, with two inputs, volume, tone, 6″ speaker and 4 watts RMS output.

Finally, the Alamo One-Niters included three more combos. The 2565 Montclair Tremolo Reverb had one channel with two inputs, volume, bass, treble, reverb, tremolo, 12″ speaker and 25 watts RMS output. The 2564 Jet-Tremolo Reverb had two inputs, volume, tone, reverb, tremolo, 10″ speaker and 10 watts RMS output. The 2566 Fury Bass had two inputs, volume, bass, treble, 15″ speaker and 30 watts RMS output.

Tube/Solidstate Hybrids (1973)

By 1973, at least, Alamo had changed its all-tube design to one with a solidstate front end and tube output. This change was made, in part, because RCA sold its tube manufacturing business to a Japanese company, leaving only Sylvania and GE as sources for tubes here.

According to a June 1973 Alamo catalog and price list from a David Wexler jobbers book, Alamo offered no fewer than 16 amplifier models that year, many, if not all, carrying familiar model names from the past. These were now divided into four ?ineups:?the Pro Line-Up, Standard Amplifier Line-Up, Tremolo Line-Up and One-Niters series. These still had squarish plywood cabinets covered in black tolex with a black and silver grillcloth. These mostly had white script Alamo logos on a little black blob of plastic glued on the upper right corner of the grill. If you thought these were Japanese imports, given their appearance, you wouldn? be the first, but you? be wrong.

The Alamo Pro Line-Up included four variants for the lead player and three for bass. Lead amps included the Model 2567 Futura Tremolo Reverb ($409.95), a combo with two heavy duty 12″ speakers, two channels, four inputs, volume, treble, bass, treble boost, reverb, tremolo, and 135 watts peak (45 watts RMS). The three remaining amps were known as the Paragon Super Reverb, each with a Model 7+79 Reverb/Tremolo Piggy Back Powerpak head. The Model 7+79 head had 210 watts peak (70 watts RMS) and basically the same controls as the Futura. The Model 7+700 Paragon Super Reverb ($585.95) added a cabinet with two heavy duty 12″ speakers. The Model 7+701 Paragon Super Reverb ($609.95) had a cabinet with one 15″ and one 12″ speaker. The Model 7+702 Paragon Super Reverb ($654.95) had a cabinet with two 15″ speakers.

Alamo Pro Line-Up bass amps included the Model 2569 Paragon Bass ($339.95), a huge combo with 120 watts peak (40 watts RMS), two channels, four inputs, volume, bass and treble controls and a single 15″ speaker. The Model 2565CW Paragon Bass Piggy Back ($399.95) ?also called the Paragon Country Western Bass ?consisted of a head version of the Paragon Bass and a single 15″ speaker cabinet. The Model 7+75 Paragon Bass Piggy Back ($559.95) ?also called the Paragon Super Bass ?had the Paragon head and a twin-15″ speaker cabinet.

The ?3 Alamo Standard Amplifier Line-Up included three combos. The Model 2562 Challenger ($91.95) had 36 watts peak (12 watts RMS), one 10″ speaker, three inputs and volume and tone control. The Model 2560 Capri ($69.95) was similar with 12 watts peak (4 watts RMS). The Model 2525 Special ($54.95) offered 9 watts peak (3 watts RMS), a 5″ speaker, two inputs and a volume control.

The ?3 Alamo Tremolo Line-Up also included three combos. The Model 2570 Twin-Ten ($189.95) ?also called the Electra Tremolo ?offered 60 watts peak (20 watts RMS), two channels, four inputs, volume, tone, tremolo, and two 10″ speakers. The Model 2563 Embassy ($115.95) had 36 watts peak (12 watts RMS), 10″ speaker, three inputs, volume, tone and a tremolo with rate and depth controls. The Model 2573 Dart Tremolo ($79.95) had 12 watts peak (4 watts RMS) with 10″ speaker, three inputs, volume, tone and tremolo.

Finally, there were three Alamo One-Niters combos in ?3. The Model 2565 Montclair Tremolo Reverb ($249.95) had 75 watts peak (25 watts RMS), one 12″ speaker, one channel, two inputs, volume, treble, bass, treble boost, vibrato and reverb. The Model 2564 Jet Tremolo Reverb ($179.95) offered 36 watts peak (12 watts RMS), one 12″ speaker, volume, tone, reverb and tremolo. The Model 2566 Fury Bass ($225.95) was an all-tube unit with 105 watts peak (35 watts RMS), one 15″ speaker, volume, bass and treble controls.

By ?3, Alamo was also offering the Model 2574 Reverb Unit with a patented reverb system, and three controls for mixer, contour and intensity.

Solidstate (ca. 1980)

By around 1980, Alamo amps had finally become all solidstate. No information is available on these, but expect them to be similar to the previous lineups.

Alamo amps continued to be made until around 1982 or so, when Alamo combined with a company called Southwest Technical Products, and the Alamo legend again became the province of politics and warriors.

It? hard to tell exactly how many Alamo guitars and amps were made. At peak production, Alamo employed around 100 people, and each year produced between 36,000 and 40,000 amps, quite a hefty number. Guitar production was much smaller, running around 1,000 annually. Assuming approximately a 10-year run, that would be about 10,000 guitars, more or less.

Dating Alamos

Dating Alamo guitars and amps will be pretty hard, except by the broad-brush historical outlines presented here. Both guitars and amps had serial numbers recorded for warranty purposes, but the whereabouts of any records, if they even remain, is unknown. Where possible, pot codes should be helpful.

The End

And that concludes our remembrance of the Alamo, and fills in yet another piece in the wonderful mosaic that makes up American guitar history. Alamo amplifiers are probably among the most underrated American instruments, and the older tube amps, while never powerhouses, are especially worth seeking out if you like that classic, warm sound. Alamo guitars, on the other hand, were at the very bottom of the American guitarmaking pecking order in terms of quality and performance. Still, they are fairly rare birds and reflect the heady days of the ?0s and the Guitar Boom, when you could sell anything with strings on it.

It? unlikely you? want to have to rely on one of these for a steady gig, but then, if you?e reading this narrative, that? probably a pretty remote consideration anyway. Any good collection of American guitars from the ?0s should have at least one example so you can properly ?emember the Alamo.?

HR NOSHADE SIZE=”1″>

Alamo Amplifiers, Hawaiian Lap Steels and Electric Spanish Guitars

What follows is an approximate listing of Alamo amps, laps and guitars, based on the reference materials at hand. Please note that there are many holes and this should be taken as a rough guideline only. Also, since cosmetic changes occurred frequently and constitute one of the few guides for dating Alamo instruments, I?e chosen to re-list various models when a design change is known. It ain? perfect, I admit, but then, how much did you know about Alamo amps and guitars before this? I? amazed we got this far!

Amplifiers

birch A cabinets

1949/50-62 AMP-3/No. 2463 Embassy

1950s-59 AMP-4/No. 2461 Jet

1950s AMP-2/No. 2462 Challenger

1950s AMP-5

by 1960-62 No. 2465 Montclair

grey leatherette, beading stripes

by 1960-61 No. 2561 Jet

by 1960-63 No. 2563 Embassy

by 1960-63 No. 2562 Challenger

by 1960-63 No. 2565 Montclair

by 1960-63 No. 2567 Paragon

by 1960-63 No. 2569 Paragon Special

by 1960-63 No. 2560 Capri

1962-63 No. 2570 Electra Twin Ten with Tremolo

1962-63 No. 2566 Century Twin Ten

1962-63 No. 2564 Futuramic Twin Eight

grey and blue leatherette

1962-63 No. 2561 Jet

colors

1962-63 No. 2460 Fiesta

1962-64 No. 2577 Altrol Electronic Tremolo and Foot Switch

grey & silver leatherette, no beading, rectangular logo plate

1963-64 No. 2560 Capri

1963-64 No. 2561 Jet

1963-64 No. 2562 Challenger

1963-64 No. 2563 Embassy

1963-64 No. 2564 Futuramic Twin Eight

1963-64 No. 2565 Montclair

1963-64 No. 2570 Electra Twin Ten with Tremolo

1963-64 No. 2567 Paragon

1963-64 No. 2569 Paragon Special

1963-64 No. 2571 Galaxie Twin Twelve

dark vinyl, metal corner protectors, black rectangular logo plate in upper left corner, vinyl strap handle

1965-66 Model 2560 Capri

1065-66 Model 2573 Fiesta Tremolo

1965-66 Model 2562 Challenger

1965-66 Model 2563 Embassy Tremolo

1965-66 Model 2565 Montclair

1965-66 Model 2570 Electra Twin Ten

1965-66 Model 2569 Paragon Bass

1965-66 No. 2568 Paragon Band

1965-66 No. 2568JL15 Paragon Band [Lansing speaker]

1965-66 No. 2567 Futura with Reverb and Tremolo

1965-66 Model 2572 Titan

1965-66 No. 2574 Alamo Reverb Unit [Hammond]

1965-66 Model 2571 Galaxie Twin Twelve Piggy Back

1965-66 Model 2571JL12 Galaxie Twin Twelve Piggy Back [Lansing speaker]

1965-66 No. 2578 Piggy-Back Super Band

1965-66 No. 2578JL12 Piggy-Back Super Band [Lansing speakers]

1965-66 No. 2576 Piggy-Back Band

1965-66 No. 2576JL15 Piggy-Back Band [Lansing speaker]

1965-66 No. 2575 Piggy-Back Bass

1965-66 No. 2575JL15 Piggy-Back Bass [Lansing speaker]

rectangular cabinets, black vinyl, black and silver grillcloth, white plastic script Alamo logo upper left corner

1967-70 Model 2578 Super Band Piggy-Back

1967-70 Model 2578JL12 Super Band Piggy-Back [Lansing speakers]

1967-70 Model 2576 Band Piggy-Back

1967-70 Model 2576JL15 Band Piggy-Back [Lansing speakers]

1967-70 Model 2571 Galaxie

1967-70 Model 2571JL12 Galaxie [Lansing speakers]

1967-70 Model 2579 Alamo Pro Reverb Piggy-Back

1967-70 Model 2575 Piggy-Back Bass

1967-70 Model 2575JL15 Piggy-Back Bass [Lansing speakers]

1967-70 Model 2569 Paragon Bass

1967-70 Model 2569JL15 Paragon Bass [Lansing speakers]

1967-70 Model 2567 Futura with Reverb and Tremolo

1967-70 Model 2566 Fury Bass

1967-70 Model 2570 Electra Twin Ten

1967-70 Model 2564 Jet

1967-70 Model 2565 Montclair

1967-70 Model 2572 Titan

1967-70 Model 2574 Alamo Reverb Unit

1967-70 Model 2563 Embassy Tremolo

1967-70 Model 2562 Challenger

1967-70 Model 2560 Capri

1967-70 Model 2573 Dart Tremolo

1967 No. 2599 Q-T Practice Aid

1970-72 2567 Futura Tremolo Reverb

1970-72 2571 Galaxie Twin-Ten Tremolo Reverb

1970-72 2575CW Paragon Bass [piggy back]

1970-72 2566 Fury Bass

1970-72 PA 200 system/PA200 Centurion

1970-72 2570 Twin-Ten

1970-72 2563 Embassy

1970-72 2562 Challenger

1970-72 2573 Dart

1970-72 2560 Capri

1970-72 2525 Special

1970-72 2565 Montclair Tremolo Reverb

1970-72 2564 Jet-Tremolo Reverb

1970-72 2566 Fury Bass

white script Alamo logo on black blob, solidstate preamps, tube output

1973-79? Model 2567 Futura Tremolo Reverb

1973-79 Model 7+79 Paragon Super Reverb with Model 7+79 Reverb/Tremolo Piggy Back Powerpak head

1973-79? Model 7+700 Paragon Super Reverb with 2×12 cabinet

1973-79? Model 7+701 Paragon Super Reverb with 15+12 cabinet

1973-79? Model 7+702 Paragon Super Reverb with 2×15 cabinet

1973-79? Model 2569 Paragon Bass

1973-79? Model 2565CW Paragon Bass Piggy Back (Paragon Country Western Bass)

1973-79? Model 7+75 Paragon Bass Piggy Back (Paragon Super Bass)

1973-79? Model 2562 Challenger

1973-79? Model 2560 Capri

1973-79? Model 2525 Special

1973-79? Model 2570 Twin-Ten

1973-79? Model 2563 Embassy

1973-79? Model 2573 Dart Tremolo

1973-79? Model 2565 Montclair Tremolo Reverb

1973-79? Model 2564 Jet Tremolo Reverb

1973-79? Model 2566 Fury Bass

1973-79? Model 2574 Reverb Unit

all solid-state

ca.1980-82 no information available

Hawaiian Lap Steels

1949/50-64 No. 2493 Embassy [pear-shape]

1949/50-64 No. 2490 Jet [triangular]

1950s Challenger

1950s-61 No. 2499 Futuramic Dual Eight

by 1960-61 No. 2497 Futuramic Eight

by 1960-61 No. 2495 Futuramic Six

1962-63 No. 2499 Alamo Dual Eight String Professional Model (Futuramic)

1965-67? Model 2493 Embassy [triangular Jet]

Electric Spanish Guitars

1960-61 No. 2590 Texan [solid]

1962-63 No. 2587 Futuramic [solid]

1962-63 No. 2588 Fiesta Spanish [Tele solid]

1963 No. 2589/2590 Titan Mark I [hollow, French curve head]

1963 No. 2591/2592 Mark II [hollow, French curve head]

1963-65 No. 2593/2594/2597 Titan Bass [hollow, 2-cut]

1964 Titan Mark I [hollow, center humped head]

1964 Titan Mark II [hollow, center humped head]

1963-64? Fiesta [solid, 2-cut, center humped head]

1964 Fiesta [hollow, center humped head, one or two pickups]

1965-66 Model 2593/