The “father and son” idea of musical lineage isn’t anything new, and it shouldn’t be surprising that more than one generation of electric guitarists has attained notice in the popular music spectrum, as more and more parents who played their share of (sometimes loud) guitar-based music is now seeing one or more offspring attempting to hone their own musical chops.

Such is the case with Austin’s John and Jake Andrews. John was the guitarist for Mother Earth, an acclaimed aggregation that started out as a latter-day “Frisco” band in the late 1960s. While the focal point of the band was vocalist Tracy Nelson (VG, April ’98), who hailed from Wisconsin, the bulk of the combo was comprised of players from Texas. John Andrews’ sojourn started several years earlier in the Lone Star State, and included more than one brush with notable musicians.

Andrews is originally from Houston, but in ’64 was playing in an Austin combo called the Wigs. The vocalist and other guitarist for that band was Boz Scaggs, who would also migrate to the San Francisco area and encounter his share of fame, first as a member of the Steve Miller Band before going on to a successful solo career. The motivation for Andrews’ own move to the Left Coast was a chance to work with the Monkees’ Michael Nesmith, an opportunity presented by former bandmate David “Spider” Price.

“I got a call from Spider. He told me Michael Nesmith wanted to put together a band of Texas musicians called the Armadilloes,” Andrews recounted. “I got hold of (bassist) Bob Arthur, and we went to Los Angeles. We were together for a few months, but then the Monkees’ TV show didn’t get renewed, so the money dried up.”

Andrews’ next opportunity came when he auditioned for Little Richard’s band.

“The auditions were at a Baptist church in Watts,” he said. “And the first day there were about 50 drummers, 50 horn players, and maybe 10 guitarists. I made the cut the first day; it was down to three guitarists, and I knew the material and the other two didn’t. So I felt sure I’d get the gig.

“But that night, I got a phone call from Travis Rivers – Mother Earth’s manager – he’s also from Texas. They’d been playing around the Bay Area for several months, and had just signed a contract with Mercury Records. They were supposed to start recording in two weeks, and they’d just fired their bass player and guitar player. Bob Arthur and I drove up that night – I never went back to the Little Richard audition – auditioned for Mother Earth, and we cut the first album, Livin’ With The Animals, in August of ’68.”

Keyboardist Mark Naftalin (VG, April ’98) was on board for the first album. He had been a member of the original Butterfield Blues Band, which included guitarists Mike Bloomfield (VG, July ’97, April ’98) and Elvin Bishop (VG, July ’97). Bloomfield also played lead on the Memphis Slim song that was also the band’s moniker, but Andrews (nicknamed “Toad” during his stint with Mother Earth) advised that Bloomfield, who was living in Berkeley at the time, was actually recruited by Nelson rather than Naftalin.

And Andrews was into vintage guitars and amps when Livin’ With the Animals was recorded. He’s seen playing a blond Fender Telecaster – a ’54 he still owns – in one photo in the album.

“Back then you could get them for less than $100,” he noted with a chuckle.

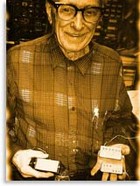

Mother Earth’s second album, Make A Joyful Noise, was recorded in Nashville, and the band ultimately moved to Music City. The combo lasted until ’76, and Andrews cited a five-day stint at the El Mocombo Club in Toronto as its final gig. While Nelson would continue to use the Mother Earth name, Andrews remained in Nashville and began buying and restoring antique ceiling fans he found in old hotels. He and a partner found encouraging demand and profit from restoring such collectibles.

“We’d have maybe $20 or $30 into each,” he noted. “And we could sell them at antique malls for about $300, so it was a huge profit margin.

“TGI Friday’s corporate office was in Nashville, and we furnished about 10 of their restaurants with 10 fans each. We bought motors from Hunter and Friday’s didn’t like the blades of the fans, so we made our own blades. George Gruhn had his GTR store back then, and he let me use his bandsaw and drill press to finish off the new blades.”

Andrews moved back to Austin in the Fall of ’77 and opened his first Texas Ceiling Fans store a few months later. In ’86 the company expanded its inventory to include full lighting fixtures, closet lights, chimes, etc.

Andrews has an enviable collection of vintage guitars – most are in a bank vault. Several were obtained during his days with Mother Earth, so he was ahead of the curve in the “old guitar phenomenon.” His main interest is in old Fenders, and in addition to the ’54 Tele he cited earlier, he also has a May ’54 Stratocaster (refinished), a matched ’53 Esquire and Telecaster set, a ’59 Custom Telecaster, and two early Broadcasters. He still owns a ’57 Bassman 4 X 10 amp he used in his tenure with Mother Earth.

Some of the instruments have celebrity connections. His ’51 Esquire was formerly owned by Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown. Brown has authenticated the guitar, and told Andrews that Leo Fender gave him the instrument. Andrews’ ’44 Martin D-18 was owned by country blues picker Sam McGee, and one of the Broadcasters belonged to Michael Esposito of the Blues Magoos (which charted in the mid ’60s with “We Ain’t Got Nothin’ Yet” and “Pipe Dream”).

Andrews also dabbled with student-grade Fender instruments, such as Musicmasters and Duo-Sonics, and recalls one “volume” purchase of budget instruments when he and Travis Rivers pooled their finances.

“We were in Houston, auditioning a drummer,” he recalled. “And we went to this pawn shop in the black section of town called Wolf’s Pawn Shop. They had three ’50s sunburst Les Paul Juniors and a Fender Duo-Sonic; at the time, I couldn’t have cared less about Juniors because I played Fenders. So Travis got the three Gibsons and I took the Duo-Sonic – we got all four of ’em for $100.”

Ultimately, Andrews refinished the Duo-Sonic and it was one of the first guitars his son Jake (born in 1980) learned to play.

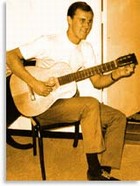

Jake’s star is now on the rise, as the young guitarist’s first album, Time to Burn (Jericho), has garnered noticeable airplay (particularlythe title track) across the U.S.

Jake acknowledges that he grew up in a musical household, even though his father wasn’t a full-time professional guitarist anymore.

“My father was pretty much out of the [music] business, but he still played at certain gigs, just for fun. I remember being around guitars ever since I was real young, and I started playing when I was about five.”

At an early age, Jake was sitting in with players like Albert King at legendary venues such as Antone’s.

Another early guitar of Jake’s was a ’53 Gibson ES-140T, a 3/4-scale instrument his dad bought as a Christmas gift when Jake was 10.

“When I was 11 or 12 I felt like I could handle a Strat,” he noted. And that model has been his instrument of choice since. He played one of his father’s clean mid-’50s Strats and some vintage reissues, then for some time played the aforementioned early-’54 Strat. He currently utilizes a sunburst ’60 model, “…but there’s not much sunburst left on it,” Jake said with a chuckle.

The second generation guitarist concurs that Time to Burn contains what many listeners will consider stereotypical “Texas tones.” But Jake noted that “…while there are some regional similarities, almost everybody’s gonna have a different style.”

Most of the album’s 13 tracks are performed in a three-piece format with occasional keyboards and horns. And the late Doug Sahm played piano on one of his own compositions, “Glad For Your Sake.”

“My father knew Doug since the ’60s,” says Jake. “We ran into him at a hotel in Los Angeles and asked him to play on the album.”

The young player also acknowledged the influence of other Texas vets in the liner notes of Time to Burn (citing Jimmie Vaughan, Carla Olson, Eric Johnson, and other guitarists), and also noted other players such as Charlie Sexton and Doyle Bramhall II.

“They’re still older than me, but I still listened to them when I was growing up.” The album is dedicated to the late Oscar Scaggs, Boz’s son.

Jake was upbeat about the reception Time to Burn had been receiving, noting that the title track had been heard in more than 120 radio markets. He’s toured with George Thorogood, The Allman Brothers Band, and the Doobie Brothers. The buzz concerning his playing and singing continues to grow.

In addition to the ’60 Strat in his current rig, Jake favors Marshall amps. “I’m always changing amp setups,” he noted. “Recently, I’ve been using a ’73 100-watt Marshall head and a ’68 4 X 12 cabinet. They sound great.”

So Jake Andrews is following in his father’s musical footsteps, even though John has gone on to a very successful post-music career. Both are appreciative of their respective personal musical histories, and both are upbeat about the future. It doesn’t get much better than that.

Photo courtesy of John Andrews. John (right) and Jake (center) Andrews at a jam with Bonnie Raitt’s original rhythm section in July of ’95.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s Aug. ’00 issue.