Best known for his work with the Red Hot Chili Peppers, John Frusciante thoroughly enjoys every aspect of making music, and continuously experiments with new and unusual ways to create it. As a teenager, Frusciante became interested in writing and recording his own music. He started making solo albums years ago, and with the luxury of having his own recording studio, Frusciante has combined personal recording techniques developed through experimentation with tricks of the trade learned from celebrated producer Rick Rubin.

Frusciante recently completed his latest solo disc, The Empyrean – a conceptual album on which he used an assortment of vintage gear. He was happy to explain his creative process for recording tracks and graciously allowed Vintage Guitar an all-access look at many of his favorite guitars. Although he does not consider himself a collector, over the years Frusciante has assembled an impressive arsenal of instruments, favoring pre-CBS Strats as his guitars of choice for use both onstage and in the studio.

How did writing and recording music for The Empyrean compare to making your previous solo albums?

The story of the album is hard to translate because it was intentionally written in an abstract way. It was a strange road for me that really started when I did my first recordings as a kid. For years, until I rejoined my band when I was 28, all I had really done as a solo artist was make recordings at home on a four-track. That’s how I made my first three solo records. So when I started recording in a studio, my only experience recording in a studio was with Rick Rubin as producer. I tried to apply that with all I knew when making Shadows Collide With People, my first solo record in a studio. I didn’t like that experience at all; I was being way too much of a perfectionist and trying to make everything sort of adhere to some kind of preconception of perfection.

From there on, I started making records really quickly, kind of as an exercise where the object was to do it as quickly as possible. I have friends who never spent more than $10,000 on a record, and I was inspired by that. So I started to make records in four or five days between the recording, mixing, and everything. That went really well. Gradually, my friend Josh Klinghoffer and I got really comfortable performing under that kind of pressure. We got really good at doing things in one take.

A few years ago, I did six records in six months like that. For this one, I had most of the songs written, so [in mixing] we took our time experimenting, doing tripped-out overdubs, and all kinds of treatments. There was no thought in making things perfect, we just wanted them to be we felt in the moment, and capture that energy.

GET YOUR VG FIX → |

|---|

We recorded very much in the spirit of the others, but rather than trying to mix 12 songs in one day, we mixed songs in two days each and spent a lot of time messing with the sound, and playing the mixing board like an instrument, trying to create atmosphere. I look at music like constructing a building, where you’re creating these artificial spaces. When you’re mixing, you shift from one atmosphere to another. Most of it was recorded on 48 tracks, and there’s a lot of shifting from one scene to another in an instant, where you’re in a different environment and acoustic atmosphere. That was all done with tape edits.

We weren’t under pressure to do it quickly or stay within a certain economic bracket. We did decide to not spend more than $10,000, and it was recorded over a period of a year – I was on tour and doing other projects, plus I wanted to do things at a relaxed pace. I think we practiced about a month, then spent a month recording and 20 days mixing.

A lot of it sounds very improvisational.

I wanted to have more jam sections. I was starting to feel there was too much “song, song, song” on my previous solo albums, though jamming and soloing have always been important parts of me, as a musician. For whatever reason, I hadn’t really gone into them much, other than on my first solo record; I wasn’t into soloing as much as playing melodies. A couple of my albums had long solos, and I wanted to do more of that. Sometimes I’d have a song that was two minutes long and it ended up being five minutes because I put a long solo on it or the original arrangement had long solos built into them that I planned as jams, for shifts in atmosphere. “Central” is a good example because it repeatedly goes from one kind of space to another.

Was that difficult after taking long breaks?

Not at all. It didn’t lose anything. I thought it might, and I like working on musical ideas when they’re fresh. When things get interrupted by a tour, it can dilute what you do. But in this case it didn’t because I waited until moments when I was really having fun working on it. So the record adhered to a concept that the music was intended to reflect, and it came together in a way that was more specific and pronounced than I expected. There was an energy motivating things that I found by making sure we worked in the same spirit as the first day of recording. I never experienced that on any record done over a long period of time.

In the middle of the process, something shifted in me, where I started thinking of music as only the act of doing it, and stopped being concerned with the prospect of making a record. I started just thinking in terms of making music that I would want to hear coming out of my speakers late at night. When people start thinking about putting out a record, there’s a whole egotistical kind of investment in it. Even if you’re an independent artist making small records, when you’re thinking in terms of making a record rather than just making music, you’re denying a huge aspect of the powers of creativity. I think it’s a more wholesome, natural approach. That mindset has worked well for me, made me look back with fondness to when I used to record on my four-track. When I did my first album, it was music for me to listen to late at night with my friends. And when we were mixing this album, that’s totally what it was about. Like I said, I like to create environments, so when you turn on certain music, your room seems like a palace.

Which are your favorite tracks on this album?

Each song was very connected with one another in what they were expressing. This album doesn’t seem like a collection of songs. It seems like a singular statement. I think of them all balancing one another.

If someone was coming over and I was only going to play them four songs, I’d play “Before The Beginning,” “Dark/Light,” “Central,” and “After The Ending” because they are specific points in the album. The music and subject matter of the lyrics arc from a low point to a high point. I wanted the feeling of reaching and then giving up, then reaching again, then giving up, then reaching again. Every time you start reaching, it keeps going to a higher peak. I wanted the music, lyrics, and subject matter to conform to a specific idea. It’s not that I like them more than the other songs, it’s just that I like how well they work. To me, “Before The Beginning” starts in the murky depths of some weird place, and I like how well it does that. Originally, the album was going to start with much more of a bang, but I realized that didn’t fit what I was trying to do in terms of the arc of the theme.

As you described, there are many different atmospheres, and it sounds like there were different setups for each song. What were you using to achieve the sounds?

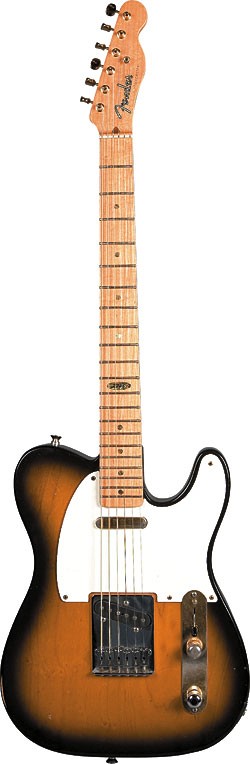

As far as guitars and gear, on all my solo recordings in the past, I never used the same rig that I use in the Chili Peppers. In the Chili Peppers, I always have a Marshall Major, Marshall Jubilee, and my old Fender Stratocasters. My main Strat is a sunburst ’62, my second favorite is a sunburst ’57 (Ed. Note: appointments suggest the Strat is actually a ’55), and my third is a red ’61. It’s interesting, the relationship between the tone when you play an electric guitar acoustically and when you play through an amp. There’s definitely a correlation between how it sounds acoustically and how it sounds through the amp. That’s my fattest-sounding guitar, acoustically and plugged in. It’s so much about the way it vibrates when you play different notes. On that guitar, there are certain frets where you hear a reverb-like sound. It has to do with the springs in the back, but it’s interesting how some guitars have certain hot spots on them and certain places feel like they vibrate more than others. It’s all stuff that gives it personality. I like working and playing around things like that. It gives you a path to travel instead of just having the full options and nowhere to go. It’s like having unlimited freedom, but not knowing what to do with it.

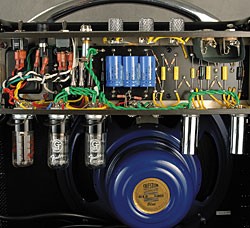

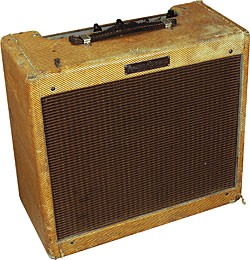

So guitars on this album were one of those three Strats and, on acoustic parts, an all-mahogany Martin. For amps, I was using both the Major and the Jubilee. I used a Fender Bassman on a few things, too. In the last few years I got deeply into what I can do with a Marshall and a Strat, as far as feedback, tone, and things like wah pedals. Because I’m into synthesizers, I started approaching the tools in the basic setup of a guitar with distortion, wah, whammy bar, and amplification. I started really looking at those as parameters, much like the knobs on a synthesizer. They’re just ways to produce different sounds. For this one, I wanted to use the same gear I use in the Chili Peppers because that is the part of me that I’ve put the most time into developing.

The main stuff for guitar sounds was that rig, and I was treating it with a modular synthesizer. So the recordings usually had nothing more than a wah pedal, distortion, and fuzz. I use the Boss Turbo Distortion pretty regularly, and an Electro-Harmonix English Muff’n tube fuzz, which has really extreme EQ and a big, thick, meaty sound. I used it on the solo for “Enough Of Me.” I turn the EQ up, but leave my guitar Tone knobs down and use either the middle or neck pickup so the initial source sound is really dark and kind of plain. If you blast the tone controls on the effect, you get a really thick, beautiful sound that reminds me of an exaggerated Eric Clapton tone in Cream, where you have this really smooth fuzz. For that solo, I was jumping from low to high notes rather than following a linear train of thought. I was kind of thinking in two ways at once by alternately playing very low notes with high notes, where the octave was displaced by a couple of octaves, and it worked really well.

I also used the Mosrite Fuzzrite a lot, and a Maestro Fuzz-Tone, which is a funny one. It’s got a cord that goes to the guitar, and there’s only an output to the amp. The E-H Holy Grail reverb is a pretty normal thing for me, and the Ibanez WH-10 is my standard wah since Blood Sugar Sex Magik. I don’t think there’s a better wah. When we were making Stadium Arcadium, there was so much wah I figured I’d use a variety of pedals and there wasn’t one that came close to the Ibanez. There are a couple of Crybabys that are cool, but for me, they weren’t as good, because I use a lot of feedback. I want something that when I put it in one position, one note is going to feed back, and when I put it in another position, another note is going to feed back. You just have more variation with the Ibanez because there’s a wider frequency range. Another pedal is a Boss Chorus Ensemble, which I use to split the signal in my rig.

And, early digital reverb units like the EMT 250, AMS, and Lexicon Prime Time were definitely a big part of the guitar sound. A lot of atmosphere was created by using those reverbs and putting them through the modular synthesizer, then doing weird things like tripping them out on the mixing board. I really like the combination of using early digital reverbs with analog synths, analog synth modules, and analog EQs. I think it’s a magical combination.

How were the synthesizers used?

I wanted to record the guitar with the effects, then take the sound off tape, run it through the modular synthesizer, and turn some of the knobs and have some of the other knobs in essence turned for me by other modules. Playing with the knobs of the synthesizer that the guitar is going through is pretty much like going through effects. It’s like hi-pass and lo-pass filters, and different kinds of phase shifting. Sometimes, I play a filter like it’s notes on a keyboard, but all you’re changing is basically where your wah is set, though you’re doing it in steps rather than in a linear way like you do it on a wah pedal. But you can jump from one frequency to another. I’m doing that at the end of “Unreachable,” which has four guitars playing harmonies, then all going into the synthesizer and playing the steps of the filter with a keyboard. So I’m playing a rhythm, kind of like a drum beat, but where the high frequencies are kind of like the snare drum and the low frequencies are like the kick drum. So it’s basically like playing a wah pedal that goes in steps, rather than in a linear fashion. So anything that sounds phasey or chorusy, or unusual for a guitar to sound like, I typically do it with modular synthesizer.

Do you have guitars set up different ways to achieve certain sounds?

I do. I use D’Addario .010s on my main guitars and the action is between high and low. Whenever I play a guitar with really low action, there doesn’t seem to be as much of a difference when I hit it really hard or when I hit it really soft – there’s less vibration in the body. I would imagine if I picked the strings lighter, I would probably do better with lower action. But I go through extremes of hitting the guitar really soft and really hard, and there’s also a difference of sound in fretting the string hard and soft.

What type of picks do you use?

I use orange .60 mm Dunlop Tortex picks. When I play with a heavy pick, it seems like there’s less difference in the sound from picking softly to picking hard. I like the acoustical relationship to the instrument and the way it vibrates the instrument more. It seems like I can apply more variation in sound by having a pick like this, depending on how you hold it. You can do the same thing you can do with a heavy pick, but a heavy pick can’t ever really do what a lighter one can do in terms of rhythm playing. I used to use heavy picks when I was a teenager and into playing fast heavy metal. But as I gradually got more into playing the textural way, I’ve used the orange Tortex picks.

What are some of your favorite instruments in your collection.

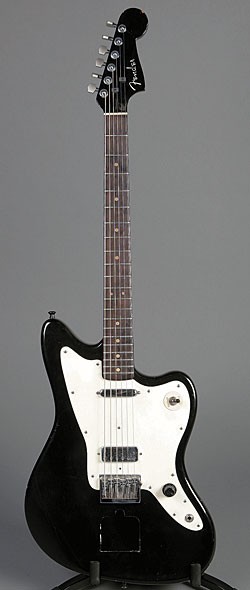

I love Fender Jaguars. The guitar I’ve owned the longest is a red Jaguar from around ’61. It has a matching headstock. I also have an old white one I transformed into a GR-300 guitar synthesizer. And I have my Gretsch White Falcons. I used to use other guitars on records to give the sound variety, but for Stadium and The Empyrean, it’s been pretty much just Strats. I also have a Gibson SG Custom from 1960 with three PAF pickups. That’s a cool guitar. Similar to what we were saying about when your action is low, because those pickups are so close together, you can’t really hit it very hard because there’s no place for the strings to dig under. You’re really limited to having just the tip of the pick hit the strings, and I think I get a lot of my sound for rhythm playing especially, and for soloing, from digging into the string with more or less of the pick, depending on the note. So I can’t really do it on that guitar and I’ve only used it for things where I want to have a smooth regularity to the sound, which isn’t that often.

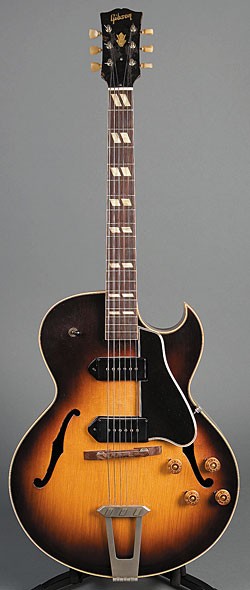

The Les Paul is a ’69, but I’m not sure what years the ES-175 and 335 are from. I don’t play those much; I bought them because Steve Howe played them, but they don’t really go with my style that well. I feel like Strats are an extension of me, and a Jaguar feels like the next closest thing to being an extension of me. Les Pauls and SGs seem like a further stretch. With a 175 or 335, I feel like a totally different person. I barely see a relationship to the way I play and the way those guitars are set up. You grow up developing a style on a Strat, and that’s what you play all the time.

I also have a red Mustang, and it’s fun. I feel like a different person on it, too, but it feels really comfortable, like an extension of me… but also that it’s a toy instead of a guitar. The same for the Duo-Sonic.

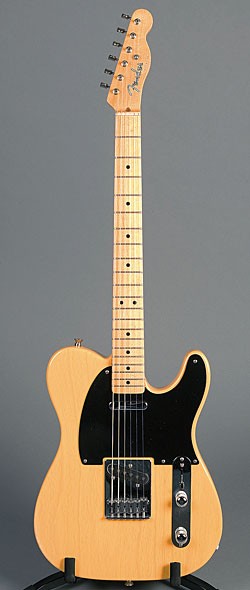

Around By The Way, I played Teles more than a Strat.

That Fender six-string bass is something I looked for and can see myself getting more into. There are certain stylistic directions I hear in my head, so an instrument like that is interesting to explore because I like playing bass. I think the P-Bass might be a ’61. I play that one at the end of “Dark/Light” on my record.

For acoustics, I wanted one like John Lennon plays on “Magical Mystery Tour.” I got one that’s similar and from that same period, around ’65. All of my acoustics are small-bodied and I wanted one that was bigger-bodied and good for chords.

I’ve had most of these guitars for a really long time. When I rejoined the Chili Peppers, I just had one guitar – the red Jaguar. I started collecting and my friend, Vincent Gallo, helped me find a lot of guitars. I specifically wanted that six-string bass because it was something I was interested in exploring, and the classical guitar that I bought, which is an Enrique Garcia; I was practicing classical guitar on tour. That St. George XK12… that thing is a pain in the ass to tune! I’d play it more if I could get it in tune. It’s not set up the best, either. The Rickenbacker used to be owned by James Burton, and that’s his special engraved tailpiece. That’s another one Vincent found because for a while I was really into James’ playing with Ricky Nelson.

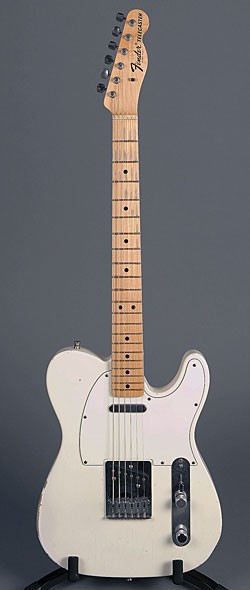

There’s a cool white early-’60s Strat that was rented to me at one point for some reason, and I just had such fun playing that I bought it. But it ended up not really being able to alternate with my other guitars; it’s the kind of guitar you can have some fun on, but it’s not really practical. If you break a string and someone hands you that guitar, you’re not going to be able to do the same thing with it at all.

As time goes by, I’ve become less interested in experimenting with different guitars and just trying to get the most I can out of a Strat with a fuzz tone. For me, there’s a certain magic in it, especially in ’60s Strats. The other day, a friend asked me to make some feedback that he could sample, and when I sat down with the amp, I was getting sounds like a ring modulator – sounds I’d never heard come out of the guitar.

There are incredible possibilities when it comes to playing really loud and with different types of distortions and fuzz tones, and using the bar and the pick, and your tension on the strings in different ways. I can’t imagine getting tired of that.

Have you kept the original pickups in your Strats?

I would like to, but they do eventually need to be changed. On my [’55], I bought it with an expert who insisted we open it up to see if the pickups were original. He and the people at the store all thought that they were original. Then years later we found out that they were Seymour Duncan Vintage Strat pickups. They are so similar to the originals that it’s hard to tell the difference in sound. I had my ’62, which has the original pickups, and then I had the [’55] with the Duncans, and the sound was very similar. The differences had more to do with the guitars than the pickups. Eventually, I had to get Duncans in the ’62, as well.

Were many of your guitars purchased to have different sounds for recording, but not intended for use onstage?

I bought them because I thought I’d play a different way on each guitar. But as time went by, I didn’t use them much. With the white Strat, it was a neat experience because it made me play different, and made the band sound different. If I hadn’t gone through a phase of buying, I never would have came upon the White Falcon and some of the others. I definitely have used the SG and Les Paul in ways that also gave the band a different sound. I had to buy different guitars to see how they’d fit into my repertoire, into my songwriting, and into my playing. So it was a valuable experience and I’m glad I bought all of them. Sometimes I go through a phase where I learn a lot of jazz, where my 175 or 335 will come in handy. You never know what kind of a direction you’re going to go. It’s just been in the last few years after going through a big blues phase and being really into Hendrix’s playing when I was doing Stadium Arcadium that I became really connected to the Strat and put all of my creative energies into it.

Which guitar is most important to you, sentimentally?

That ’62 Strat.

Is there a guitar you’re still searching for, or something you’ve always wanted?

There is; I’d love to have a ’59 Les Paul. For years, I really wanted one and they just kept shooting up in price. I really feel like there’s a war between people who think artistically and people who think with a business sense. Across the board, I think the world would love for people who think artistically to start thinking with more of a business mind. Just as a matter of principle, you don’t buy a guitar just because it’s a good investment. Then you’re thinking of something you’re supposed to be making music on and being creative with as something that has some sort of monetary value or economical benefits. I just don’t feel that’s a good way to think of an instrument, and it’s the same with so many things. I like paintings, but I don’t want to buy paintings just because I think of them as something I could sell one day. I want to look at them and think of them as something that makes me happy. I’d rather look at the paintings my goddaughter made me than look at something and think, “I can sell that one day.”

I’ve been offered ’59 Les Pauls, and I’d love to play one. But they’re just too expensive to rationalize. I think it’s important, as an artist, to never feel that anything having to do with music is judged by its price. What you can do with it is much more important than how much it costs. If collectors who don’t play guitars didn’t buy them, their value would be based on what players feel they’re worth. But when the people who would really use them don’t get the chance, it’s a real shame.

This article originally appeared in VG‘s April 2009 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.