-

Jim Carlton

Bill Pitman

The Man From The Wrecking Crew

On a recent episode of his TV talk show, David Letterman mentioned to guest Cher that he’d just seen the new documentary, The Wrecking Crew, which chronicles the coterie of L.A. studio musicians that helped create many of her records and hundreds of other hits for more than three decades. She immediately responded by naming

-

Jim Carlton

Johnny Smith

An American Treasure

Jazz guitarist Johnny Smith died at his home June 11, 2013, two weeks shy of his 91st birthday. Arguably the most respected and revered guitarist of the modern era (1950 to present), Smith was sincerely humble and reserved about his extraordinary talent. In 1999, his peers and friends celebrated his career with a gala at

-

Jim Carlton

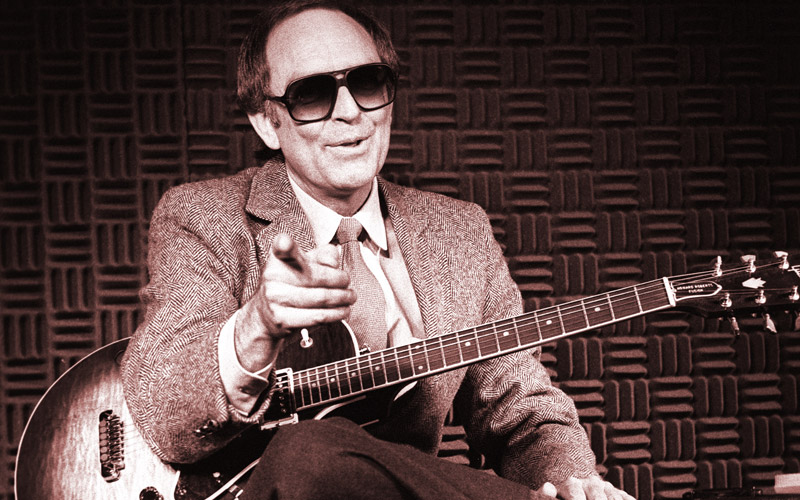

Howard Roberts

H.R. Was a Dirty Guitar Player!

In his prime, Howard Roberts played more than 900 studio dates annually and recorded the hippest guitar records of the era. His legion of fans still revere his incalculable influence and musical legacy. Vesta Roberts, who grew up in a family of lumberjacks, gave birth to Howard just three weeks before the Wall Street Crash

-

Jim Carlton

Mary Osborne

Charlie’s Angel

Jazz guitar pioneer Mary Osborne was the only female guitarist to realize a significant impact on jazz in the 1940s and ’50s – and many aficionados agree that her swinging style earned her confirmation as one of the early architects of R&B and rock and roll. Born July 17, 1921, in Minot, North Dakota, Osborne

-

Jim Carlton

Billy Bauer

Jazz Guitar’s Hidden Giant

Billy Bauer’s career was so steeped in tradition that he is often thought of as one of the first jazz guitarists. And while that’s true, his pioneering, progressive attitude and contribution to the artform endured for decades. His big-band time with Woody Herman’s First Herd was a precursor to his association with jazz visionary Lennie