-

Bret Adams

Outlaws

Rising Tides

By the mid ’70s, Southern rock emerged as one of the most-exciting and successful genres in pop music, thanks to the Allman Brothers Band and Lynyrd Skynyrd. Another important early Southern-rock band making its mark with country influences was Outlaws – the Tampa group nicknamed “Florida Guitar Army.” Rhythm guitarist Henry Paul, lead guitarists Hughie

-

Bret Adams

Dan Hawkins

Toast of the Town

When The Darkness roared out of England with its 2003 debut Permission to Land and the hit “I Believe in a Thing Called Love,” the music world was slapped across the face. The band reminded people that melodic hard rock steeped in ’70s influences was supposed to be catchy, fun, and sometimes outrageous. Guitarist Dan

-

Bret Adams

Mike Campbell

Got Lucky

Mike Campbell is one of the most-heard guitarists on earth thanks to his work in the legendary Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers and their catalog of hit singles (“American Girl,” “I Need to Know,” “Refugee,” “The Waiting”) and certifiably classic albums (Damn the Torpedoes, Hard Promises). He has also written for and played with many

-

Bret Adams

Mike Campbell with Ari Surdoval

Heartbreaker: A Memoir

In his autobiography, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers guitarist Campbell admits he’s quiet and shy. Self-doubt plagued him his entire life, and when problems arose in the Heartbreakers, a lack of confidence had him blaming himself first, even when he wasn’t responsible. Perhaps his attitude was psychologically rooted in his impoverished childhood and coming from

-

Bret Adams

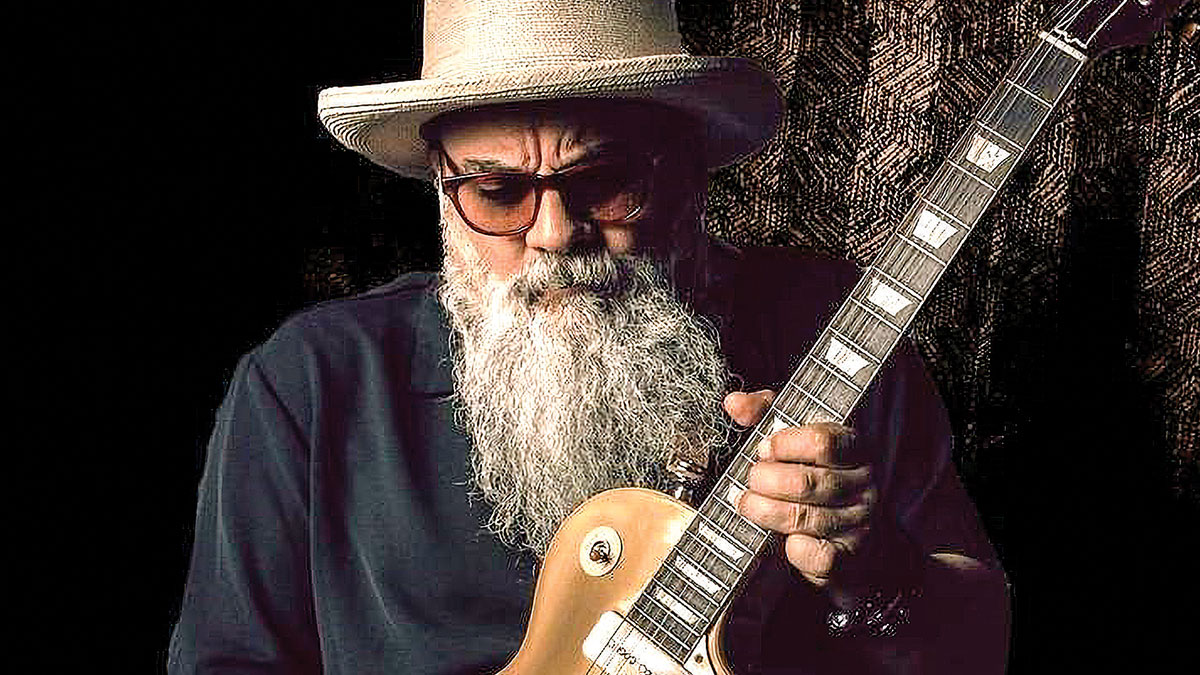

Jimmy Vivino

Gonna Be 2 of Those Days

A veteran vocalist/guitarist/keyboardist and purveyor of blues, R&B, and rock’, Jimmy Vivino has an incredible résumé. A longtime fixture in Conan O’Brien’s house band, he has played on movie, radio, and Broadway projects and worked with Levon Helm, Hubert Sumlin, Al Kooper, Jimmie Vaughan, Donald Fagen, Warren Haynes, Laura Nyro, along with innumerable others. He’s

-

Bret Adams

Thin Lizzy

The Acoustic Sessions

Thin Lizzy’s first studio release in decades, this album reimagines tracks recorded 50+ years ago by the trio of vocalist/bassist Phil Lynott, guitarist Eric Bell, and drummer Brian Downey. The songs are from Lizzy’s first three albums – 1971’s Thin Lizzy, ’72’s Shades of a Blue Orphanage, and ’73’s Vagabonds of the Western World. Recently,

-

Bret Adams

Steve Hackett

No Limits

Steve Hackett is one of the busiest guitarists around, regularly issuing new studio and live albums. His latest, Live Magic at Trading Boundaries, focuses on his classical/acoustic compositions. Included are solo guitar pieces and group performances featuring music from his time in Genesis during its beloved ’70s “progressive” era. Trading Boundaries is an intimate venue

-

Bret Adams

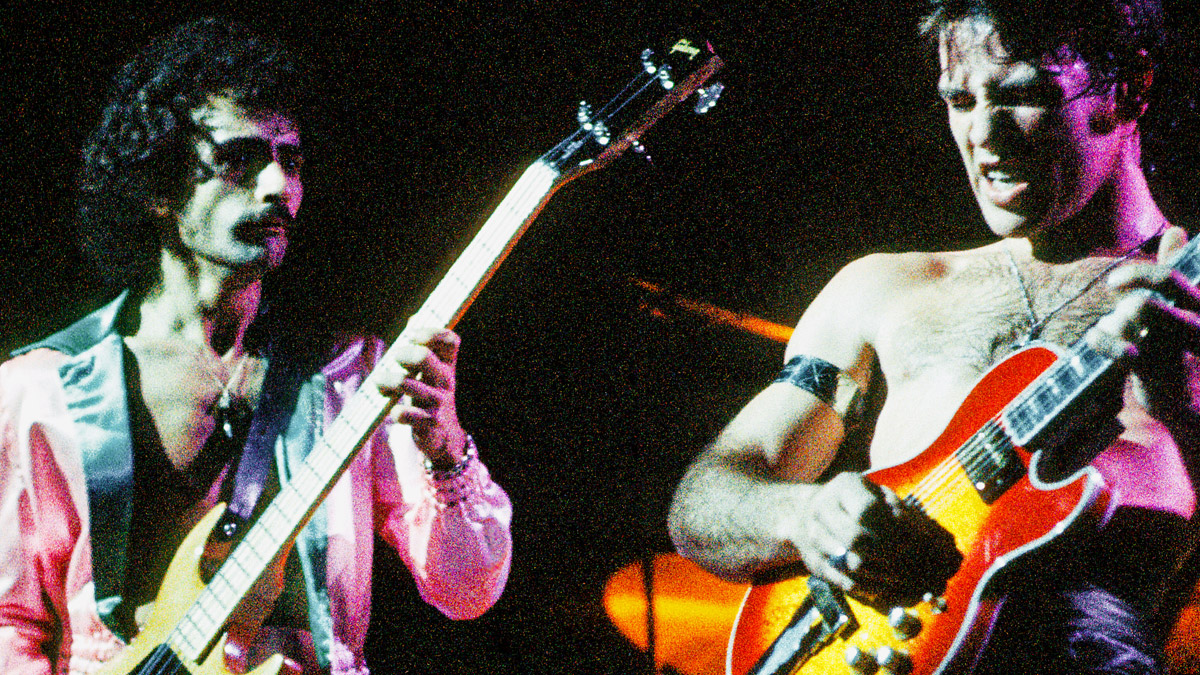

Pop ’N Hiss: Grand Funk’s We’re An American Band

Rockin’ Patriots

Thundering out of Michigan in 1969, Grand Funk Railroad quickly became one of the most popular bands in the world. In just three years, vocalist/guitarist Mark Farner, bassist Mel Schacher, and vocalist/drummer Don Brewer released five studio albums, became a major concert attraction, and scored Top 40 hits with “I’m Your Captain (Closer to Home),”

-

Bret Adams

Albert King with Stevie Ray Vaughan

In Session (Deluxe Edition)

Talk about a summit – this session was a Luke Skywalker-meets-Yoda moment. The live album, originally released in 1999, is finally available in its entirety on LP, CD, and high-resolution digital formats. Backed by an exceptional band, King and Vaughan were filmed at CHCH-TV in Hamilton, Ontario, on December 6, 1983. King was the seasoned

-

Bret Adams

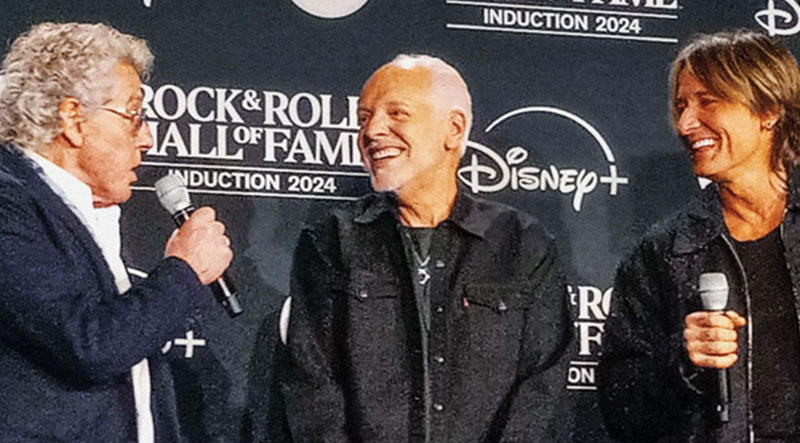

Frampton, Foreigner Join HoF

Rockin’ the Hall

Peter Frampton, Foreigner, Alexis Korner, and John Mayall became classmates during the 39th Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony, held October 19 in Cleveland. Frampton, who is battling the degenerative muscle disease inclusion body myositis, was inducted by The Who vocalist Roger Daltrey. Frampton performed “Baby (Somethin’s Happening)” before Keith Urban came out