In early 2009, VG columnist Peter Stuart Kohman turned his focus on Burns, the pioneering British guitar builder. We’ve compiled installments 9, 10, and 11 for this special edition of VG Overdrive. See the complete history.

Despite Ormston Burns Ltd’s many successes, by 1965 the chronically under-capitalized English company was in a precarious financial situation. Jim Burns needed a savior with deep pockets, and fast.

At the same time, American piano and organ builders Baldwin were concerned that the boom in the guitar sales was passing them by. With years of explosive growth, guitars were the “in” trend, as pianos and organs slipped. The company made a bid for Fender in 1964, but were beaten out by CBS. By the summer of ’65, Burns approached Baldwin to distribute his products in the U.S. but the deal turned into an outright purchase. Paperwork was signed September 30, and Baldwin had its guitar division, while Burns was spared from bankruptcy (details on this can be found in an extensive feature by Michael Wright and Baldwin’s own Steve Krueger in VG’s February ’01 issue, and can be seen at vintageguitar.com).

The U.K. company was called Baldwin-Burns LTD; in the U.S. and Canada, simply Baldwin Piano and Organ Company. English promotional materials carried the tagline, “Baldwin guitars designed by James O. Burns”; presumably, the Burns name was still considered an asset in the U.K.. Soon after the takeover, Baldwin issued a series of brochures showcasing the “new” line. Each showed two re-branded instruments from Burns, all models receiving a new three-digit stock number beginning with 5. Baldwin initially seemed concerned with supplying as many guitars as possible to get their U.S. sales program running, and any existing instruments and parts were fair game. The U.K.’s Beat Instrumental magazine from January ’66 carried a news item that said, “Because of the vast amount of exporting to the states, nearly all models of Burns guitars are practically out of stock. Solids are doing extremely well in the states, especially the Marvin.” Considering the lack of time to market them and scarcity of Marvins in the U.S., this is likely just PR fluff! Baldwin shipped a large number of their new babies to the U.S. as soon as they could, especially the designed-for-export Baby Bison – quite a few early-’66 models can still be found here.

Production was ramped up for the much larger U.S. market, but initially the “transition” instruments were made at the Burns factory in Romford the same as they had been. Many early Baldwins carry dated inspection stickers under the pickguard; these can have dates reaching back six months or more; obviously all available parts were being assembled into guitars, even the slower-selling ones! These first Burns-to-Baldwin instruments were re-branded any way they could be. As most carried the company logo on the pickguard, the easiest solution was to rout that section of the guard and glue a “Baldwin” plaque over it. Collectors refer to this as the “cut-in” logo. Instruments Like the Marvin and Bison with “segmented” pickguard were particularly easy to re-brand – the logo plate was a separate piece anyway!

An early Baldwin sales one-sheet included a nice assemblage of transition instruments. The ad was for the Howard combo organ, but tellingly, the guitars are up front! All the instruments are Burns-built models with the new company logo – the Jazz bass features the “cut in” logo, while the Double Six and Virginian have new “Baldwin” guards. The rare black-finished Jazz Split Sound in the center has the second stage “Baldwin” engraved pickguard, but is early enough to still have an unbound fingerboard – a feature usually seen on Burns instruments, and a good example of the mixed parts you see on these half-and-half models. Collectors, note: very few, if any production instruments were double-logo’d “Baldwin-Burns”; a Marvin S prototype reportedly built for Hank himself is one of the few verifiable examples. I have seen several instruments over the years where “Burns” has been cleverly engraved directly above “Baldwin” on the logo plate; as with all collectible guitars examine carefully, and caveat emptor!

The first overall change made by Baldwin was to put binding on all necks, which became common by early ’66. Another mostly unnoticed feature was a neck-tilt adjustment similar to what Nathan Daniel had developed several years earlier and CBS/Fender would add to some instruments in the early ’70s. A large screw under the plastic neckplate on the back (just below the gearbox truss rod adjustor) can be turned to raise or lower the neck angle, provided you remember to loosen the lower two neck screws first! This feature was not mentioned in Baldwin literature and may have been added to speed final assembly by eliminating the need to shim poorly fitted necks.

This would become a concern because by mid ’66, the relatively small Burns Romford facility was clearly overtaxed. Sufficient for the home market, the line couldn’t cope with the projected numbers needed for the U.S. Baldwin also quickly discovered that the tariff and shipping costs were astronomical – the same problem that stymied Burns itself! The solution was to keep the Romford facility building complete guitars only for the U.K. and foreign markets, while ramping up the fabrication of parts. Instruments for sale in the U.S. would be sent to Baldwin’s Arkansas organ plant as unassembled components. There were tax and efficiency advantages to this plan, but this is where U.K.- and U.S.-built instruments start to diverge; Arkansas-assembled guitars most U.S. players are familiar with often display a poorer fit and generally sloppier feel than those finished by the “old guard” at Romford.

Jim Burns had been retained in a managing director position as part of the purchase agreement. As the larger company’s focus moved away from creating new products to making and selling existing ones, Jim himself became a redundancy. Like Leo Fender, he was an “ideas” man, only happy when working on new products. Ironically, both men became superfluous to the companies they’d founded in 1965-’66, when the corporate mindset took over. Burns stayed at Baldwin/Burns for the contracted year, redesigning some hardware, but further new product development was abandoned. Perhaps as a last gesture, his final designs for the company – the six-pole bar-magnet pickups and newer short Rez-O-Tube units – had “Designed by James O. Burns” written directly on them.

In the meantime, Baldwin threw more money into promotion. The initial slogan was “The Best Sound Around” and quite a number of trade ads were taken in the U.K. and U.S. music press featuring different models. By early ’67, the company issued a large, complete, and colorful catalog (the cover was featured in our guitar cheesecake celebration some months back). This touted the instruments’ supposed “Fundamental Features” and the extensive prose was in many ways straightforward and more convincing than Burns’ earlier florid (if prosaic) sales material, even if it was groaningly pseudo-hip in spots! All models were pictured in full-page living color and there was some nifty Peter Max-style flower-power artwork, as well. Unfortunately, Baldwin’s sales force seemed to have little clue how to tap into the guitar market, which was actually just past peaking as they were gearing up to sell the new line. The company’s piano and organ dealerships were hoplessly ill-equipped to sell guitars and amps, and Baldwin sales did not have the jobber connections to effectively market the line elsewhere. Meanwhile, all those guitars shipped to the U.S. started to pile up in the warehouses…

The guitar line presented in ’67 was more streamlined, the herd having been culled and eccentric/eclectic features tamed so production could be more standardized – a strategy some longtime Burns employees applauded.Indeed, the Romford team seemed to have had generally good relations with their Baldwin overlords, unlike the situation developing at CBS/Fender. Still, the instruments began to lose their Burnsian character.

The flagship Marvin (Baldwin Model# 524, seen in the ’66 ad) and Shadows Bass (Model# 528) now featured a new redesigned neck – the original carved scroll headstock (Hank Marvin’s request) had been a bear to produce. Factory manager Jack Golder designed a new, streamlined head with a sort of lump at the top that was far easier to carve, and wasted less wood as well. This neck became the “standard” Baldwin pattern, and the instruments’ de facto trademark; although not all necks were exactly the same. The varying scale lengths persisted on different models and necessitated at least three distinct but similar necks be produced. For the most part, the Marvin was otherwise unaltered, although fit and finish sometimes seemed to suffer. A few late Marvins appear fitted with the “bar magnet” pickups used on most other models. The Shadows’ Bass got a redesigned Rezo-Tube tailpiece, and the pickups were changed to a four-pole model of the new “bar magnet” unit first seen on the Baby Bison; this pickup soon appeared on nearly all Baldwin basses. Metal-button Van Ghent tuners – soon used across the line – replaced the plastic variety on the new headstock.

This use of universal parts became Baldwin strategy; it made sense from a production standpoint, but robbed the instruments of individual character. The Double Six (Baldwin Model# 525) was the only Burns design that survived the transition unchanged, gaining only a bound fingerboard in early ’66. The Bison guitar (Model# 511) and bass (Model# 516) remained the most distinctive Burns creations, but were hardly promoted and appear to have been built in small quantities after mid ’66. The bass received the same alterations as the Shadows Bass; the guitar adopted the new flat-scroll headstock, and the Jazz Split Sound (now Model# 503) was adapted to the new standard neck but kept its trademark short scale. The electronics were simplified somewhat (one internal coil was deleted) but the sound little altered. The matching Jazz Bass (Model# 519) underwent a more radical revision to adapt it to the standard 30″-scale “lump scroll” bass neck, losing its distinctive medium-scale format and gaining a squatter, less attractive appearance. It, too, was made in very limited numbers from this point, but the guitar remained a good seller, and one of the most common Baldwin instruments today. The Baby Bison (Model# 560) also saw some revisions, with the standard headstock replacing the idiosyncratic V shape of earlier models and a new short-plate Rez-O-Tube unit. Extra-small pickguard plates were added to the previously uncluttered face. A matching bass using standard components was introduced at this point (Model# 561); this was the final piece to round out the solid line. An early casualty was the budget solidbody Nu-Sonic; the guitar (model 500) and bass (Model 522) were both gone by mid ’66.

The hollowbody line changed far more radically. The Vibra-Slim (Baldwin Model# 548) was totally rethought; whether Jim Burns had much hand in this is unknown, but it seems likely. The model lost its set neck, semi-hollow body, and pickguard-mounted controls, and essentially became a hollowbody Baby Bison, with the same style bolt-on lump-scroll neck, Bar Magnet pickups, Density wiring, and short Rez-O-Tube vibrato. The now-cheaper Vibra-Slim became one of Baldwin’s most popular models, though there was already trouble selling the model at full price by ’67! The Vibraslim bass (Model# 549) was similarly re-styled, and built in fairly large numbers. Jim Burns’ more jazz-oriented GB-65, GB-66, and GB-66 Deluxe were all early casualties; introduced in ’65, only the Deluxe model lasted even into late ’66, and it was gone by ’67. Interestingly, the Virginian (which looked like an amplified flat-top, even though it was really a semi-hollow electric) prospered under Baldwin, albeit with several design changes. The neck went to the standard style, pickups were changed and the “short” Rez-O-Tube vibrato was fitted – the Virginian became essentially a flat-top Vibraslim! Baldwin also continued production of some of the ill-fated transistor Burns amps for the U.K. and introduced an extensive U.S.-built line of amplifiers for the home market, including the E-1 Exterminator, famous as a component of Neil Young’s stage rig.

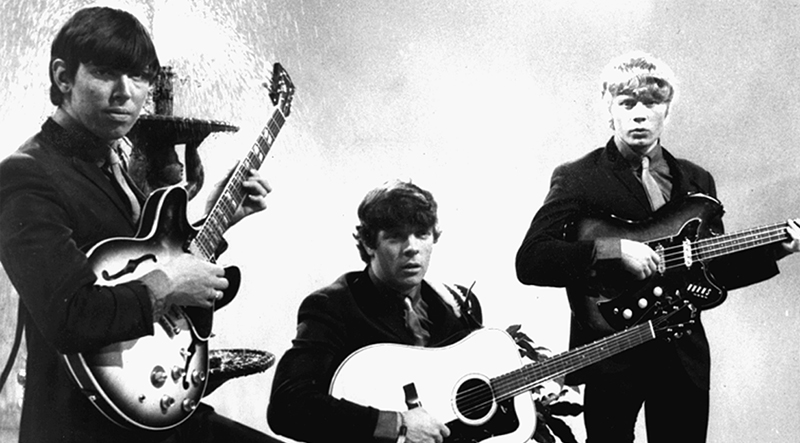

At the time, Baldwin didn’t have much professional endorsement. In the U.K., the Shadows remained faithful, but their influence was reduced. Among U.S. groups, The American Breed, best remembered for the hit “Bend Me Shape Me” appear to have been the top standard bearer. The band appeared with Baldwin instruments on their first LP (a Marvin, an earlier-style Vibraslim, and a later Jazz Bass) and in advertisements in ’67 with the Marvin and 700-series hollowbodies. Spanky & Our Gang appeared on “The Ed Sullivan Show” performing “Sunday Will Never Be The Same” with a nice collection of early Baldwin – a Double Six, Jazz Bass, and Vibraslim in red sunburst. They don’t appear to have done any print promo for the company, so it’s hard to know if this constitutes an endorsement.

Some success came in country music. Baldwin began to distribute Sho-Bud pedal steel guitars, and moved into their Nashville office. A promo shot (suitable for framing!) features Sho-Bud founder Shot Jackson and his wife, Donna Darlene, pickin’ and grinnin’, Donna on an early-’66 Baldwin Virginian with Burns features. Willie Nelson was also a Baldwin endorser who used several products, especially the proprietary electric classical pickup patented by Baldwin (not Burns) in ’65, but not commercialized until later. Long after Baldwin had packed in its guitar operation, Nelson remained faithful to the pickup, which was later installed in his Martin! There also exists a late Vibraslim bass with a “Willie Nelson’s Bass Guitar – Presented to Terry Bock” plaque on it!

Despite standardized production, the ex-Burns guitars were still expensive to build, so Baldwin made attempts at designing instruments for a lower price point. The first was an ill-fated 600 series which never made it to production, designed in Fayetville using Burns parts. What did emerge in some numbers by ’67 was the 700 series. These double-cutaway thinline hollowbodies had hardly any Burns bloodline, just Italian-made bodies and electronics fitted with the Baldwin neck. Two six strings, two 12-strings, and a bass were offered with identical styling. A U.K. ad for the models still claims “Designed by James O. Burns,” which is spurious. These were sold at the lowest price of any Baldwin guitars, and thus fulfilled their purpose, though they added little to the company’s legacy.

Further troubles plagued the line. Burns’ polyester finish often cracked soon after application, a worsening of issues seen even before the transition. Sales remained below expectations, but the entry into the guitar business had given Baldwin an overall boost. Then in May of ’67, Baldwin got the sort of guitar operation they really wanted – Gretsch. Once Baldwin owned a well-known high-profile guitar (and drum) company, their own brand mattered less. Insiders recall Baldwin demanding the Gretsch sales force “get rid of Baldwin guitars” before selling their own product. A Gretsch price list from ’69 still shows the full line of Baldwins; by this point, a serious general decline of the market was affecting all guitar sales. Most accounts say the Romford factory finally closed circa 1970, but few guitars have surfaced with stamped dates past ’67. In all, a sad end for the fretted dream started by Jim Burns in a Victorian basement 10 years earlier, and an all-too-typical tale from the ’60s.

As noted early in this series, the Burns brand was revived in 1991 under the guidance of Barry Gibson, with Jim Burns’ involvement. Burns passed away in ’98.

This article originally appeared in VG October 2009 issue. All copyrights are by the author and Vintage Guitar magazine. Unauthorized replication or use is strictly prohibited.

Dig into VG’s vast article archive!

Be notified when the next “Overdrive” and other great offers from VG become available! Simply submit this form.